My favorite Dr. Seuss tale is The Lorax, which I remember from childhood—in part because of my one-and-only attempt at knitting. The tangled result was a scarf that my sister dubbed a “thneed” after the purported all-purpose but ultimately useless garment sewn from the story’s decimated Truffula trees.

The book, which Theodor Geisel wrote in a mere 90 minutes on the back of a laundry list while traveling in Kenya, tells the story of the faceless Once-ler, who arrives in an Edenic land of tufty fluffy Truffulas, cuts them down at a rapid pace, and transforms this lush world into a smoke-choked wasteland bereft of wild inhabitants. Despite the pleas of the Lorax—a mustachioed creature who pops out of a stump—the Once-ler does not stop his depredations until the very last Truffula is gone.

One recent night, I read the words “I am the Lorax. I speak for the trees” to my children and felt my voice catch. It seemed to me that the book’s message is as relevant now as in 1971, when it was unenthusiastically received. (Geisel biographer Donald E. Pease says that readers found the book “out of keeping” with the “zany wild nonsense rhythms and figures” of earlier Seussian works.) Although The Lorax later garnered accolades and now has sold more than 1.2 million copies, the world still seems incapable of heeding its message.

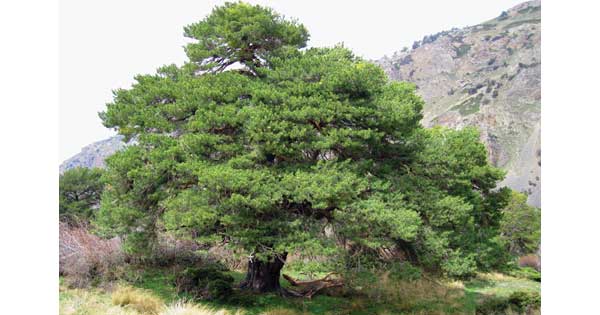

Case in point: a study published in the journal Science in late 2012 on “large old trees”—such as Mountain Ash in Australia, Baobob trees in Africa, and redwoods in California—showed that populations of these trees are “rapidly declining in many parts of the world.” The research, led by David Lindenmayer of Australian National University, notes that large old trees “provide nesting or sheltering cavities” for up to 30 percent of all birds and animals in some ecosystems. They store carbon, attract pollinators, and “provide abundant food for numerous animals in the form of fruits, flowers, foliage, and nectar.” Despite their vital role, they are still subject to multiple threats including logging, wildfires, over-grazing, and land-clearing, as well as air pollution, diseases, and insect invasions.

The news isn’t all bad. As the researchers point out, plant growth may accelerate in some tropical forests thanks to rising levels of carbon dioxide. In fact, a recent Nature magazine global survey of 600,000 trees of 403 species showed that most trees grow faster as they age, which implies that large, mature trees may fix and store much more carbon from the atmosphere than small, young trees. The article’s lead author, Nate Stephenson of the U.S. Geological Survey, writes, “If human growth would accelerate at the same rate, we would weigh half a ton by middle age and well over a ton at retirement.”

All the more reason to treasure our arboreal legacy. As Lindenmayer and his co-authors write, “Just as large-bodied animals such as elephants, tigers, and cetaceans have declined drastically in many parts of the world, a growing body of evidence suggests that large old trees could be equally imperiled.” In the absence of measures to protect them, “these iconic organisms and the many species dependent on them could be lost or greatly diminished.”