Still Wilderness

What are we feeling when we are feeling joy? And where inside us does that feeling reside?

Paul Tillich once said of the word faith that “it belongs to those terms which need healing before they can be used for the healing of men.” The word joy may not be quite so wounded, though I have noticed, as I have been gathering poems for a project I have been working on, that it tends to provoke conflicting responses. There is the back-slapping bonhomie of the evangelically joyful, who smile as if to say, “Even you, Old Sludge, dire poet—of our party at last!” There is academic detachment: is joy merely an intensification of happiness or an altogether other order of experience? And is it something of which one can be conscious at all, or is it so defined by immersion in a present tense that consciousness as we conceive it is precluded? There is affront: ruined migrants spilling over borders, rabid politicians frothing for power, terrorists detonating their own insides like terrible literal metaphors for an entire time gone wrong—“how with this rage shall beauty hold a plea,” as Shakespeare, staring down his own age’s accelerating grimace, wondered. I took on this project because I realized that I was somewhat confused about the word myself, and I have found that, for me, the best way of thinking through any existential problem is with poetry, which does not “think through” such a problem so much as undergo it. Subjected to poetry’s extremities of form and feeling, what might that one word, joy, in these wild times, mean?

Here is the definition of joy from Merriam-Webster:

1a:

the emotion evoked by well-being, success, or good fortune or by the prospect of possessing what one desires: delight…

2: a state of happiness or felicity: bliss

3: a source or cause of delight

If you’re musing on the general meaning of joy or sitting down to write an article on the subject, this might be of some use as a place to start. But if you are trying to understand why a moment of joy can blast you right out of the life to which it makes you all the more lovingly and tenaciously attached, or why this lift into pure bliss might also entail a steep drop of concomitant loss, or how in the midst of great grief some fugitive and inexplicable joy might, like one tiny flower in a land of ash, bloom—well, in these cases the dictionary is useless.

Here is an alternative, from the Scottish poet Norman MacCaig:

One of the many days

I never saw more frogs

than once at the back of Ben Dorain.

Joseph-coated, they ambled and jumped

in the sweet marsh grass

like coloured ideas.The river ran glass in the sun.

I waded in the jocular water

of Loch Lyon. A parcel of hinds

gave the V-sign with their ears, then

ran off and off till they were

cantering crumbs. I watched

a whole long day

release its miracles.But clearest of all I remember

the Joseph-coated frogs

amiably ambling or

jumping into the air—like

coloured ideas

tinily considering

the huge concept of Ben Dorain.

It is a real pleasure to ponder the small stops of kinetic clarity this poem manages. The river ran glass in the sun. Jocular water. The cantering crumbs that the hinds become in a distance that is both literal and lost, observed and remembered. And of course there are those Joseph-coated frogs, which don’t leap out of the actual into the mythological, but bring the myth smack-dab into matter. Thus “One of the many days” names and consecrates all of the days, even as it gives form and pledges fidelity to a single one. And just as the frogs are probably not really “considering” the concept of Ben Dorain, so the poet, perhaps, and all of us along for the ride with him, stand in relation to some larger reality that this poem at once implies and denies: yes, there is that word miracles, but it is obvious that they have no existence apart from the actual. These metaphysical resonances are not added to the poem but implicit within it. God is a ghost only to those who haunt their own lives, the poem might be saying. Or: God is a given for those who fully inhabit their own lives (a “joy in which faith / is self-evident,” as the Polish writer Adam Zagajewski says). The word God is both inevitable and extraneous to this poem, as is the word joy. “One of the many days” describes a moment of consciousness in which, as MacCaig puts it in another poem,

Space opens and from the heart of the matter

sheds a descending grace that makes,

for a moment, that naked thing, Being,

a thing to understand.

“Joy is the present tense, with the whole emphasis on the present,” writes

Kierkegaard. This is accurate insofar as it accords with the feeling of joy, which can banish all the retrospective and anticipatory mental noise we move through most of the time. But to define joy as present tense is to keep it fastened to time, and that doesn’t feel completely right. It might be truer to say that joy is a flash of eternity that illuminates time, but the word eternity does sit a bit lumpishly there on the page. Let’s try this from the American poet Sarah Lindsay:

Small Moth

She’s slicing ripe white peaches

into the Tony the Tiger bowl

and dropping slivers for the dog

poised vibrating by her foot to stop their fall

when she spots it, camouflaged,

a glimmer and then full on—

happiness, plashing blunt soft wings

inside her as if it wants

to escape again.

Here is another poem in which joy is not mentioned, but I would argue that it is a moment of joy that has enabled Lindsay to see her happiness. What is the difference? Let the poem be the guide. Something intimately related to time but ultimately beyond it, something as remote and inconceivable as a comprehensive awareness of one’s entire life, and yet as near and ordinary as a small moth, has broken into and illuminated—and perhaps even suggested the final fruition of?—time. Note just how much work that one word “plashing” is doing in this scrupulously plain-spoken poem. It is as if the moth has entered from another element, or has momentarily transformed the element into which it has come, where everything is so slow and singularly itself that it seems to be suspended in water.

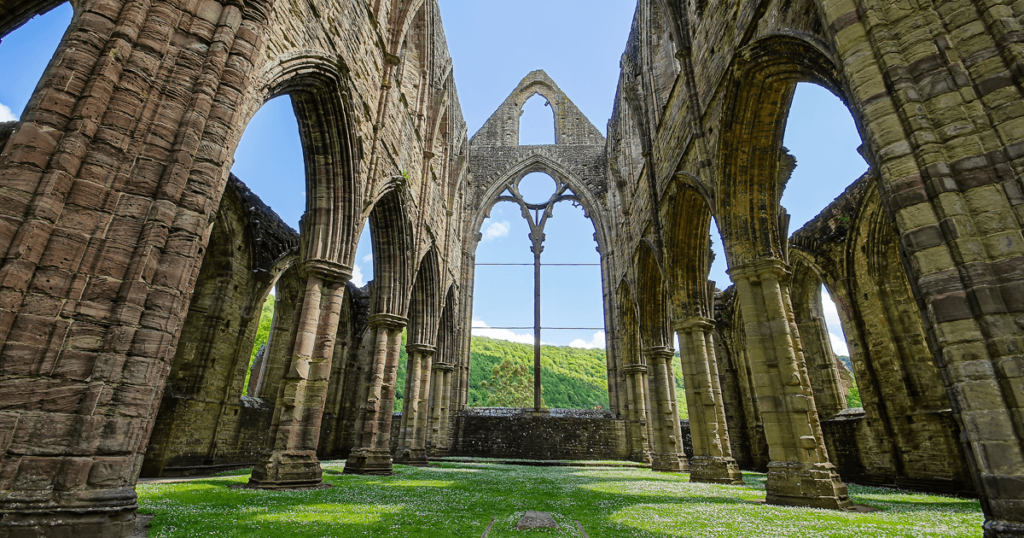

A moment of insight, then, a spot of time, in William Wordsworth’s language—and indeed Wordsworth is the great English poet of joy. MacCaig’s four lines have their origins in a famous passage from “Tintern Abbey,” which Wordsworth wrote in 1798 after returning as a young man to a landscape of his childhood:

These beauteous forms,

Through a long absence, have not been to me

As is a landscape to a blind man’s eye:

But oft, in lonely rooms, and ’mid the din

Of towns and cities, I have owed to them,

In hours of weariness, sensations sweet,

Felt in the blood, and felt along the heart;

And passing even into my purer mind

With tranquil restoration:—feelings too

Of unremembered pleasure: such, perhaps,

As have no slight or trivial influence

On that best portion of a good man’s life,

His little, nameless, unremembered, acts

Of kindness and of love. Nor less, I trust,

To them I may have owed another gift,

Of aspect more sublime; that blessed mood,

In which the burthen of the mystery,

In which the heavy and the weary weight

Of all this unintelligible world,

Is lightened:—that serene and blessed mood,

In which the affections gently lead us on,—

Until, the breath of this corporeal frame

And even the motion of our human blood

Almost suspended, we are laid asleep

In body, and become a living soul:

While with an eye made quiet by the power

Of harmony, and the deep power of joy,

We see into the life of things.

Precision in poetry happens in different ways. The most obvious is imagistic, like that “vibrating” dog in Lindsay’s poem (or like most of the scene setting that precedes the passage I have quoted from “Tintern Abbey”). Language drapes the world like dew and sharply clarifies a scene that, inevitably, it only glosses. There are vast differences of degree here, from simple description to blazing revelation, but the emphasis is on the eye. Sometimes, though, when the poet’s ear is as finely tuned as her eye, the words can seem to penetrate the world at which they are aimed—MacCaig’s “jocular water,” for instance, the fluent crispness of which conjures the river it describes, or Lindsay’s “blunt soft wings,” which are themselves monosyllabic wing beats. And then sometimes, as with music, a poem can acquire a formal dynamism that is much greater than its parts, an almost metaphysical precision, in which the sonic currents don’t merely imitate but seem to participate in the very existence of what they describe. Seamus Heaney has pointed out the effect of panoramic suspension combined with exacting particularity that one gets from Wordsworth’s poetry (especially The Prelude). I would take it one step further. The eye is suspended over the earth, but the ear is immersed within it, as if the poet were hovering over what he is also inside.

Form matches theme here. The passage above is in many ways a classical depiction of a moment of joy, yet Wordsworth is careful to make joy only one of the catalysts. The other component, according to Wordsworth, is the awesome formal harmony of nature, which has made the speaker quiet, receptive, and able to see into the life of things. True vision, the poem says, is reciprocal: the world looks back at the eye that is strong enough (fortified by memory, alert to goodness) and weak enough (made quiet, the ego not eradicated but refined) to see it.

Why shouldn’t this be so? There is a connection, after all, between the life of things and human life. We are both, quite literally, resurrected stars, compacted of the same random atoms, and we now know for a fact what in 1798 Wordsworth was only intuiting: some particles are so intimately related that they cannot be described independently and can communicate (are “entangled”) over apparently limitless distances of space and time. It is a great mystery—and at times a great horror—to ponder the link between man and matter, the intimacies that our visions reveal, and that our daily lives so routinely violate. “Are we to think,” asks the philosopher Jacques Maritain, “that in such an experience, creative in nature, Things are grasped in the Self and the Self is grasped in Things, and subjectivity becomes a means of catching obscurely the inner side of Things?” Reading Wordsworth, I would say yes.

The definition of joy in the passages by Wordsworth and MacCaig, though both are tethered tightly to the natural world, remains pretty abstract. Even “Small Moth,” clear as it is on the elements of one woman’s happiness, is elusive about that moment of joy. This may be inevitable, though maybe all poems of joy—maybe all poems, period—are aimed against whatever glitch in us or whim of God has made our most transcendent moments resistant to description. (A “revenge of a mortal hand,” is how the Nobel laureate Wisława Szymborska defines the joy of writing.) The great Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai once wondered why it is that we have such various and discriminating language for our pains but become such hapless generalizers for our joys. “I want to describe,” his poem “The Precision of Pain” concludes, “with a sharp pain’s precision, happiness / and blurry joy. I learned to speak among the pains.”

“Among the pains” is where we all learned to speak. The instant the link between word and world appears, so does the rift between them. (I met a Czech scholar once, a man of immense learning and multiple languages, who told me that he didn’t speak a word until he was five years old. “Everything was okay until then,” he said with a shrug.) This link/loss aspect of speech seems true no matter one’s metaphysical dispensations. You don’t need to believe that the meaning of the word love—or even, say, rock—has been plumbed in order to maintain that language has not exhausted it.

Still, as I have been suggesting, joy is quite particular in its resistance to particularity. What is it we are feeling when we are feeling joy? In Lisel Mueller’s poem “Joy,” someone breaks into tears upon hearing a passage of beautiful music:

It’s only music. And it was only spring,

the world’s unreasoning body

run amok, like a saint’s, with glory,

that overwhelmed a young girl

into unreasoning sadness.

“Crazy,” she told herself,

“I should be dancing with happiness.”But it happened again. It happens

when we make bottomless love—

there follows a bottomless sadness

which is not despair

but its nameless opposite.

It has nothing to do with the passing of time.

It’s not about loss. It’s about

two seemingly parallel lines

suddenly coming together

inside us, in some place

that is still wilderness.

Still wilderness. The place that is most us yet remains beyond us. (“You are in me deeper than I am in me,” says Augustine of God.) The particles of burned-out stars that are, or are trying to be, still on fire. (“You’ll feel light gliding across the cornea / like the train of a dress,” writes the Romanian poet Nina Cassian.) All this intimate and alien energy, all this rejuvenating and ravening matter, stilled.

Now what, one might fairly ask? After one has seen into the life of things, after the moment that is still wilderness has evaporated into the demanding and utterly domestic next, after one has looked up from the tiny miraculous moth to find oneself right back in plain old Tony the Tiger time—now what?

Pain, for one thing:

Joy’s trick is to supply

Dry lips with what can cool and slake,

Leaving them dumbstruck also with an ache

Nothing can satisfy.

—Richard Wilbur

But this is a special kind of pain. (“It’s not about loss,” as Mueller says.) It is a homesickness for a home you were not aware of having. A longing you hardly knew you had has been both answered and—because now there is nothing you want more than to have, not this experience again exactly, but the larger one that it let you glimpse—intensified. But there’s no forcing it. Clamoring after joy leads only to fevered simulacra: an art of professional echoes and planned epiphanies, the collective swells of manipulative religion, the manufactured euphoria of drugs. Thus do addictions begin. (Yes, art can be an addiction.) So what does one do with this moment of timelessness when one is back in time?

Nietzsche felt that this distinction between time and timelessness was itself a primary metaphysical problem, and weakness. To isolate any one moment outside of time, to privilege it above all others, even to want such a thing—all this is to betray, and be defeated by, time itself. Joy, though inevitably tragic because death is absolute, is the very lifeblood of being and ought to be sought and seized at every moment of existence. It is an extreme philosophy that few could follow, though one poet does come to mind, the good old rock-eating human-hating Robinson Jeffers, who actually saw Nietzsche’s scathing wager, and raised it:

Though joy is better than sorrow joy is not great;

Peace is great, strength is great.

Not for joy the stars burn, not for joy the vulture

Spreads her gray sails on the air

Over the mountain; not for joy the worn mountain

Stands, while years like water

Trench his long sides. “I am neither mountain nor bird

Nor star; and I seek joy.”

The weakness of your breed: yet at length quietness

Will cover those wistful eyes.

For Jeffers the whole notion of joy is misguided and suggests some moral rot at the center of the species. Better to live like the stars and the mountain, the dark vulture hovering watchfully over the weaker meats.

These criticisms are at once bracing and frustrating. It’s worth having one’s spiritual complacency—whether it’s a too-modest sense of one’s own existential power and volition or a too-easy sinking into an oceanic oneness with the universe—checked. It’s worth being reminded, and made to feel, besides its splendor, the brute, material necessity that is also at the heart of being, as well as the autonomy we retain when being crushed by it. But are we to assume, then, as Jeffers insists, that our moments of heightened awareness and communion are illusions, or that, pace Nietzsche, they merely show what we ought to be feeling at every second? What would it really look like to live with such molecular indifference or constant existential orgasm?

I suspect that for most of us the “ache” at the end of Wilbur’s poem, the longing that “nothing can satisfy,” will seem all too familiar and, no matter how much or how little faith we have, ineradicable. Wilbur himself, after all, is a practicing Christian. He may very well mean “nothing but God,” but the poem is careful not to say that, and its reticence is not merely a matter of form and modern metaphysical decorum. To state such a thing, to name the experience and its source in such an authoritative way, would be to betray everything that made the experience what it was. The question that Wilbur’s poem raises, then, the question that all of the poems I have been discussing raise, remains: Now what?

This is where that earlier objection becomes germane: namely, that even to speak of joy in these times, much less to claim to feel it—and much, much less to exhort others to feel it—might be an obscenity in the face of so much human suffering. Jack Gilbert’s poem “A Brief for the Defense” addresses this issue directly:

Sorrow everywhere. Slaughter everywhere. If babies

are not starving someplace, they are starving

somewhere else. With flies in their nostrils.

But we enjoy our lives because that’s what God wants.

The irony is a rhetorical strategy here (the title tells us we’re in a trial, after all), designed to elicit liberal sympathies with a shared smirk. Those idiot Christians, one thinks, taking all those New Testament injunctions to rejoice as excuses to consume, yee-hawing out of a million megachurches like elated locusts. The speaker of Gilbert’s poem knows the strangeness, the apparent offensiveness, of his message (as would have, by the way, those early audiences of Paul and others, many of whom might very well have made their way home past rows of crucified corpses designed specifically to eradicate all cause for any insurrectionist hope or joy). There is joy in the gutters of Calcutta, Gilbert’s speaker says, and the sex slaves laugh in the cages of Bombay. I suppose these things are true, but they are so remote and exotic that they are likely to seem, for the typical reader of this poem, like props. Again, this is for effect, mirroring the way we tend to reach for extreme examples—like Ivan with his newspaper clippings of atrocities in The Brothers Karamazov—when arguing about ethics or theodicy. When the heart of Gilbert’s argument comes, it does so with such knowing clarity—and, for modern poetry, such rare, sincere didacticism—that it feels like we are no longer judge or jury but in the dock:

If we deny our happiness, resist our satisfaction,

we lessen the importance of their deprivation.

We must risk delight. We can do without pleasure,

but not delight. Not enjoyment. We must have

the stubbornness to accept our gladness in the ruthless

furnace of this world. To make injustice the only

measure of our attention is to praise the Devil.

If the locomotive of the Lord runs us down,

we should give thanks that the end had magnitude.

Back to irony, just a tad, in those last two lines, but the more intimate and immediate argument, the one that bears on our daily lives, has been delivered. Joy is the only inoculation against the despair to which any sane person is prone, the only antidote to the nihilism that wafts through our intellectual atmosphere like sarin gas. More than that: joy is what keeps reality from being sufficient unto itself, which is to say, it is what keeps reality real, since in this world of multiverses and quantum weirdness, where 95 percent of the matter and energy we know only to name as “dark,” it is obvious that reality extends far beyond what our senses can perceive. So what in the world, or what beyond the world, is calling to us when we are called to joy? “It is true that the unknown is the largest need of the intellect,” writes Emily Dickinson in a letter, “though for it, no one thinks to thank God.”

For poets—and maybe for all artists after Romanticism—Gilbert’s poem can’t help but bring to mind an artistic and psychological dynamic that has become so much a part of collective consciousness that artists themselves can become unconscious of the extent to which their work is burdened by it. Light writes white, as the old saying goes. I have seen this expression attributed to numerous writers, including (and this may be the most likely source) the anonymous ones of Tin Pan Alley. In any event, you get the idea: if all is well with your life, if you have around you every creature comfort, including some dear creature you love more than art, then when you sit down to make said art, what you will find is … white: the page stays blank. Art emerges out of tension, the thinking goes, out of absence and lack. It is always the expression of, and always the only remedy to, some essential insufficiency. For the true artist, then, to slip into happiness is to betray one’s nature. “What is a poet?” asks Kierkegaard. “An unhappy person who conceals profound anguish in his heart but whose lips are so formed that as sighs and cries pass over them they sound like beautiful music.”

No doubt there’s some truth to this idea, which is itself beautifully formulated (and for Kierkegaard, one suspects, that most literary of philosophers, a bit wistfully reflexive and self-exonerating). If language separates us from the world it makes available, if even joy brings its own unique grief, it follows that to be conscious at all is to be conscious of loss. But this is what a man in my childhood used to call a watermelon wisdom: sweet in pieces but hell to swallow whole.

The one abundance you can count on in this life is lack. An artist need not go looking for it, much less empower it unnaturally by laying her gift down in front of sadness like a sacrifice. If anything, a modern artist might have to lean the other way, might have to seek out and sing her moments of happiness and joy, if only to balance the scale. Robert Lowell, who suffered from manic depression and became as famous for his miseries as for his verse—indeed the two can be very difficult to disentangle—said late in his life that, when looking back, what he chiefly remembered was the happiness. This is not entirely surprising if you read Lowell’s biography, for he was a caring and charismatic person, capable of genuine relationships of all kinds. No, the surprise comes when reading through the thousand or so pages of Lowell’s collected poems, which reveal no hint of that happiness—quite the opposite, actually. “We asked to be obsessed with writing, / and we were,” Lowell wrote, a bit ruefully, in a late elegy to John Berryman. But surely if what one most remembers and values from a life is the happiness, and one’s lifelong obsession has entirely failed to capture that, then in some major way the poetry itself has failed. Here’s how that Gilbert poem ends:

To hear the faint sound of oars in the silence, as a rowboat

comes slowly out and then goes back is truly worth

all the years of sorrow that are to come.

Lovely as that last image is, however, and as truly as it establishes relative values in one’s own emotional and aesthetic economy, Gilbert’s poem still sits somewhat uneasily against the early images of suffering. One moment of joy may very well be worth all the suffering that one must undergo, but is it also true that one’s enjoyment is worth the suffering of others, however extreme? Of course it isn’t, and the poem is aimed directly at the fallacy of this calculus. I do feel, though, that the poem avoids, or fails to account for, the revolutionary force of pure joy. Or rather the revolutionary force of a joy that, in this world, is inevitably impure, compounded as it is of eternity and time, praise and pain. As the theologian Jürgen Moltmann writes,

Joy in life’s happiness motivates us to revolt against the life that is destroyed and against those who destroy life. And grief over life that is destroyed is nothing other than an ardent longing for life’s liberation to happiness and joy. Otherwise we would accept innocent suffering and destroyed life as our fate and destiny. Compassion is the other side of the living joy. We don’t accuse God because there is suffering in the world. Rather, we protest in the name of God against suffering and those who cause it.

Compassion is the other side of the living joy. Yes, and compassion can include fury and lead to action. In his poem “Slim in Atlanta,” Sterling Brown imagines a world in which “niggers” (to avoid the word would be to betray the poem) must do all of their laughing—must express all of their joy—closed up in telephone booths. Slim finds this so outlandishly hilarious that he has to bolt to the front of the line and close himself up inside the booth so he can explode. He laughs so hard and for so long that eventually he has to be taken away by ambulance. The poem ends:

De state paid de railroad

To take him away;

Den, things was as usural

In Atlanta, Gee A.

“Slim in Atlanta” was written in the 1930s, when Jim Crow laws extended into every aspect of southern society and were enforced with a contagious brutality. Never mind the separate lunch counters and drinking fountains; simply failing to yield the right of way to a white driver could result in a beating. Or worse. Lynchings were still common and sometimes involved not simply the “perpetrator” but family and friends as well. In 1946, not far from Atlanta, a white mob, upset that a black man accused of attacking a white man had been granted bail, killed the suspect, his wife, and another black couple on hand. Still unsated, and rightly certain of their immunity (not a single charge was ever filed), the mob cut the fetus out of the pregnant woman from the second couple and made sure it was dead, too. Not so funny anymore, old Slim, whose acid laughter and weaponized irony (the fake dialect is part of this) are a long way from Gilbert’s lonely, consoling rowboat under the stars. “If we warn against irony as a seducer,” says Kierkegaard, “we must also praise it as a guide.”

I hope it’s apparent by this point that poetry itself—the making of it, certainly, but also the remaking of it as the reader—is often a form of joy. Indeed, in C. S. Lewis’s famous memoir Surprised by Joy, an early encounter with poetry is one of the three experiences of disabling/enabling joy to which he attributes his eventual conversion. Lewis describes a seismic shock, the kind that happens only a handful of times in one’s life. Certainly there are lesser joys, which are still clearly distinguishable from mere pleasure. After years of living with “Tintern Abbey,” I still feel a transcendent shiver from the poem, partly because it describes so well experiences that I have had in my life, but mostly because of the soul-conjuring and soul-compelling currents of the verse itself, the terrestrial fidelity married to atmospheric immensity, the way one feels, as Wordsworth puts it in The Prelude, the “huge and mighty forms” of nature that “moved slowly through the mind,” and are the mind.

“That joy could be reborn out of the annihilation of the individual, is only comprehensible from the spirit of music.” Thus Nietzsche again. And thus Gerard Manley Hopkins, who updates Wordsworth by making some aspect of nature, and thus of God, in some way dormant, quiescent, even expectant, until it is catalyzed by human consciousness:

These things, these things were here and but the beholder

Wanting; which two when they once meet,

The heart rears wings bold and bolder

And hurls for him, O half hurls earth for him off under his feet.

Thus Kay Ryan, who peers stoically, jokingly—but hopefully!—into the abyss of oblivion to find her “ideal audience,” who is just one person, perhaps, maybe not even born yet, maybe long dead, but who in any event

will know with

exquisite gloom

that only we two

ever found this room.

Thus Fanny Howe’s “ecstatic lash / of the poetic line,” and whatever it is that “freaks / forth a bluet” for James Schuyler, and the “Sweet sweet sweet sweet sweet tea” (it’s that last “sweet” that’s inspired) that Gertrude Stein uses to describe a Spanish flamenco dancer in 1913:

Sweet sweet sweet sweet sweet tea.

Susie Asado.

Susie Asado which is a told tray sure.

A lean on the shoe this means slips slips hers.

When the ancient light grey is clean it is yellow, it is a silver seller.

Obviously, one is not meant to understand this in the way one understands a newspaper article or even in the way one understands most poetry. You are meant to get lost in its vertiginous precisions, the weird syncopations of syntax and skin. You are meant to feel something of what Stein felt: joy.

That tired word. Appropriated by Fifth Avenue and the Third Reich (the Nazis had a real affinity for, and belief in, the raw power of Freude), used to peddle soap and salvation, the word requires some work to rehabilitate. (As do, no doubt, the many discriminations of emotion that the word encompasses.) Sometimes it is most gratifying to come across poems about joy where one least expects to find them: the hard-won somber celebration of life by that übergrinch Philip Larkin in “Coming,” the weird ride on God taken by the sacred atheist (and Holocaust survivor) Paul Celan in “With wine and being lost,” the unabashed admiration and adoration that Sylvia Plath—already neck-deep in the rising waters of sorrow that would soon take her in—lavishes on her child in “You’re.”

Snug as a bud and at home

Like a sprat in a pickle jug.

A creel of eels, all ripples.

Jumpy as a Mexican bean.

Right, like a well-done sum.

A clean slate, with your own face on.

Joy: that durable, inexhaustible, essential, inadequate word. That something in the soul that makes one able to claim again the word soul. That sensation more exalting than happiness, less graspable than hope, though both of these feelings are implicated, challenged, changed. That seed of being that can bud even in our “circumstance of ice,” as Danielle Chapman puts it, so that faith is suddenly not something one need contemplate, struggle for, or even “have,” really, but is simply there, as the world is there. There is no way to plan for, much less conjure, such an experience. One can only, like Lucille Clifton—who in the decade during which I was responsible for awarding the annual Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize for lifetime achievement was the one person who let out a spontaneous yawp of delight on the phone—try to make oneself fit to feel the moment when it comes, and let it carry you where it will:

why

is what i ask myself

maybe it is the afrikan in me

still trying to get home

after all these years

but when i wake to the heat of morning

galloping down the highway of my life

something hopeful rises in me

rises and runs me out into the road

and i lob my fierce thigh high

over the rump of the day and honey

i ride i ride

This essay is adapted from the introduction to Joy: 100 Poems, forthcoming in October, which is edited by Christian Wiman.