It rained heavily this morning, so my young children pulled on their wellies and puddle-jumped their way up the street. We spotted a fat snail, its eye-tipped tentacles slowly extending and retracting, and snapped a close-up. We took care not to step on it and squash it.

If I were the Mama in Puddles, a 1997 children’s book by Jonathan London, I might not be so thrilled about puddle-splashing and snail-spotting. The girl and boy in the book spend the morning slogging through wet grass, watching worms “squirm and stretch,” and “celebrating all the new water and new life.” But when they return home, their mother howls, “You’re wet!”

I like to encourage my own girl and boy to take an interest in the natural world, but also in the human-made world we see under construction all around us. In doing so, I believe, I’ll be nurturing an interest in science that will be sustained across the years, and perhaps that will encourage them to pursue a career in science, technology, engineering or math—the so-called STEM fields. This attitude, sadly, is often not reflected in the books I read to my children. In that fictional world, mothers and daughters are scared of insects; they shun mud and dirt and seem to devote their time to domestic tasks.

In “The Bug Box,” (from the authorless Tell-a-Tale Stories for Boys, published this year) Max heads to the garden, “where Dad was busy digging and Mum was hanging out the washing” to find a pet of his own. He gathers a spider, a caterpillar, some busy ants, a friendly centipede, and a shiny beetle. Proud of his “cool” new pets, Max bursts into the kitchen, where his mother is scrubbing dishes. “AHHHHH!” screams mother, flinging her rubber-gloved hands in the air. Max looks worried. “Mum doesn’t like creepy crawlies,” says Dad, laughing.

Classic classroom stories aren’t particularly kind to girls, either. According to the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, research shows that “teachers call on boys more often than girls, ask boys more higher-order questions, give boys more extensive feedback, and use longer wait-time with boys than girls [….] Girls are rarely chosen to give a demonstration or help with an experiment.” In Richard Scarry’s Great Big Schoolhouse of 1969, girls’ silence is to be commended, especially when learning to count: “When those little girls stop talking, how many quiet girls will there be? There will be two quiet girls when they stop talking.” When learning how to make things, Kathy embroiders a handkerchief, Frances knits a sweater, Penny weaves a table mat, and Mary cuts and folds paper to make a dollhouse. Arthur also folds paper—he makes an airplane.

In many books for small children (including the wonderful Milo Armadillo (2009) by Jan Fearnley) fathers are absent or nearly absent and are never seen in nurturing roles—a phenomenon that perhaps reflects the 27 percent of American families that are now one-person households, according to the latest census figures. An exception is I Love You Daddy (2013) by Melanie Joyce, in which a loving bear dad takes his son to collect honey, play roly-poly, and show him “the way to secret places.” The cub tells his dad, “You let me get all muddy when we dig underground, and then do it again because Mummy’s not around.”

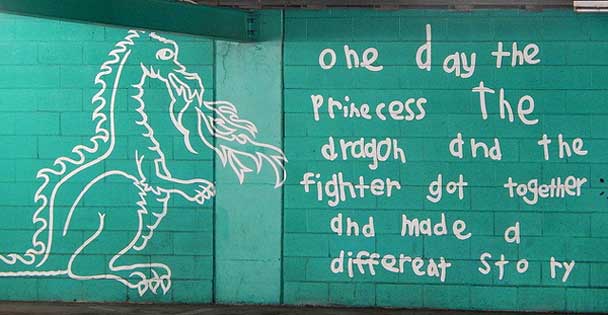

My choice of titles is highly selective, and yes, there are fine books that show girls fighting dragons (The Paper Bag Princess by Robert Munsch) or collecting rocks and sparrows’ eggs (Odd Velvet by Mary E. Whitcomb). When I look at my kids’ loaded bookshelves, however, I find that these titles are still overwhelmed by the array of books about pea-sensitive princesses or passive heroines like Cinderella.

Some stereotypes may reflect the mores of an earlier, less enlightened era. Later editions of Richard Scarry’s Best Word Book Ever, first published in 1963, were revised so that the “pretty stewardess” is now a flight attendant, the “fireman” is now a firefighter, and “girls are generally added, using bows (for better or worse) as a signifier,” writes Lisa Wade, an associate professor of sociology at Occidental College in Los Angeles.

Maybe that is why I was a bit disappointed by an otherwise fantastic toilet-training book published in 2008. In Even Firefighters Go to the Potty by Wendy Wax and Naomi Wax, a series of professionals interrupt their busy days to use the bathroom. Of 10 careers depicted in the story—firefighter, policeman, baseball player, construction worker, doctor, astronaut, waiter, pilot, train engineer, and zookeeper—only one, the doctor, is a woman. Even the polar bear, who “goes outside,” is a male. Why is there only one potty-going professional role model for girls?

We hear a lot these days about the decline in interest in science and math when girls hit puberty, perhaps because of stereotypes associated with these careers. (In one study of 8th and 9th graders, students who liked physics were perceived as more “masculine.”) From my own reading of these stories, I suspect that such stereotypes are implanted in children’s minds much earlier.