Take Me Away From Here

Nine books to transport you to other lands as you face the growing number of days at home

Nothing makes the mind seize like confinement. The size and nature of the cell—whether you’re stuck in a job or a town, a waiting room or a tiny apartment, bounded by age or youth or pandemic—matters less than the way it drains you, and seems to erase the horizon. One traditional antidote to this sense of limitation has been travel. Another has been reading. And when both came together, humanity’s most powerful literary genre, travel writing, was born.

I can say this and get away with it because almost any successful story is about travel—about transportation—in one way or another. Sometimes the journey involves geography: a desert crossed, a mountain climbed. Sometimes it’s a spiritual pilgrimage, or a tour through unfamiliar ideas. But no matter where they are set, or how many miles unspool between the covers, the best travel books open doors within us, and deliver us to views, lives, landscapes, and problems we’ve never encountered.

This list is not comprehensive. The titles here range from somewhat old to ancient, and would not fit neatly into the travel-writing section of the bookstore. But in these viral times, here are some of the books that I hurriedly carried into quarantine, or wish that I had. Books I return to and rely upon for transport of one kind of another even as I—and the rest of the world—are told to stay home.

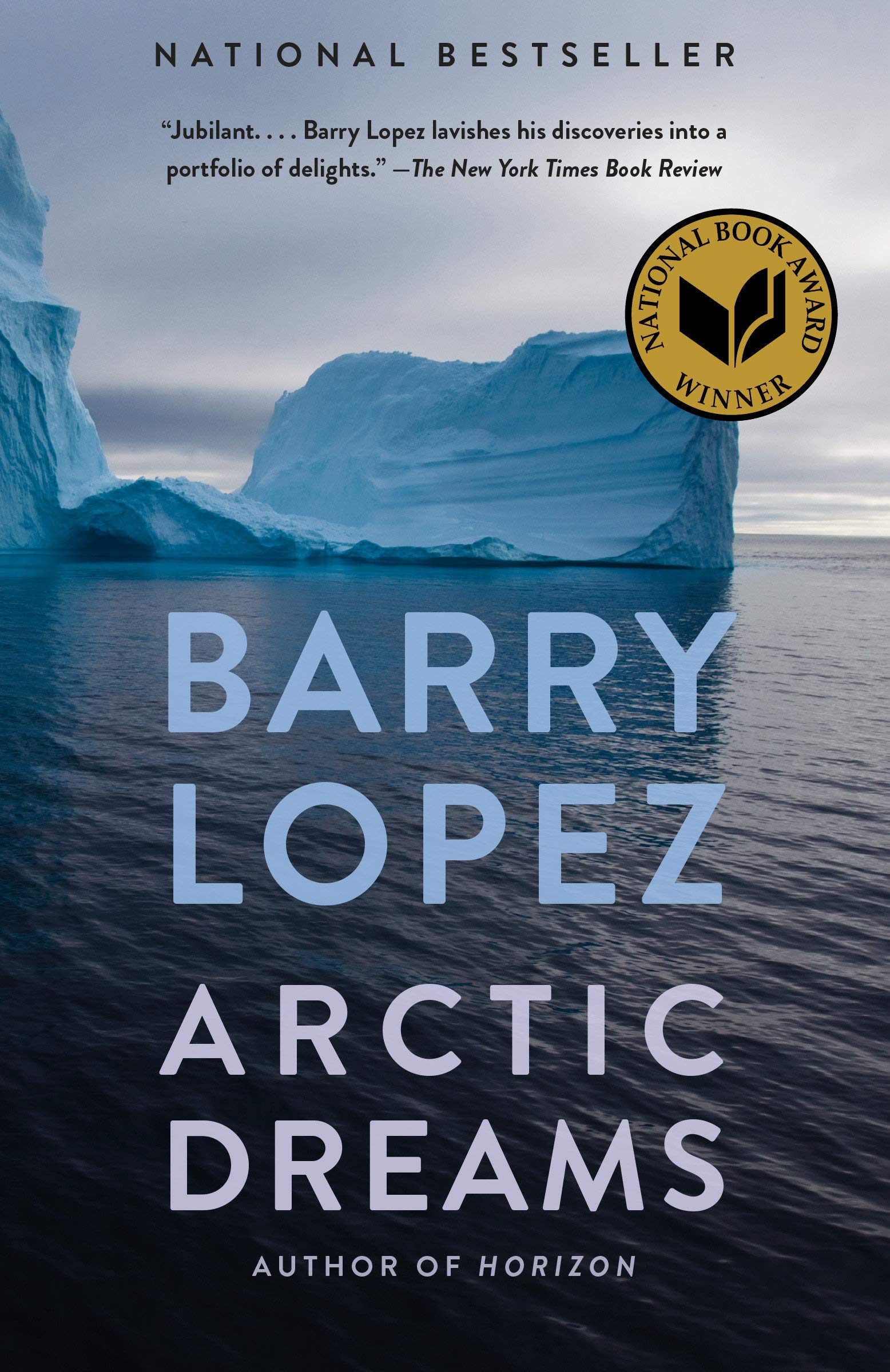

Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez

How many copies of Barry Lopez’s masterwork do I own? I’m not sure anymore. I buy the book whenever I see it and then give it away to people who haven’t read it. The polar world that Lopez wrote about in 1986 has already disappeared, so to read Arctic Dreams is in some ways a lament. But to immerse yourself in the universe of this story is to follow him outside of time and, to see the animals and people as he does is simply one of the most transformative journeys a reader can make.

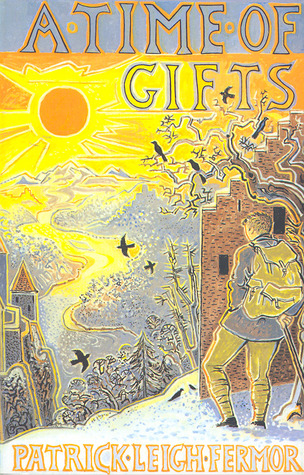

A Time of Gifts by Patrick Leigh Fermor

The journey we all might’ve made—and might yet make—if only we could only trust the world as Patrick Leigh Fermor did. His journey on foot across Europe is also one through a now-vanished world, the time between the two world wars. And it’s as beautiful as walking into a fable.

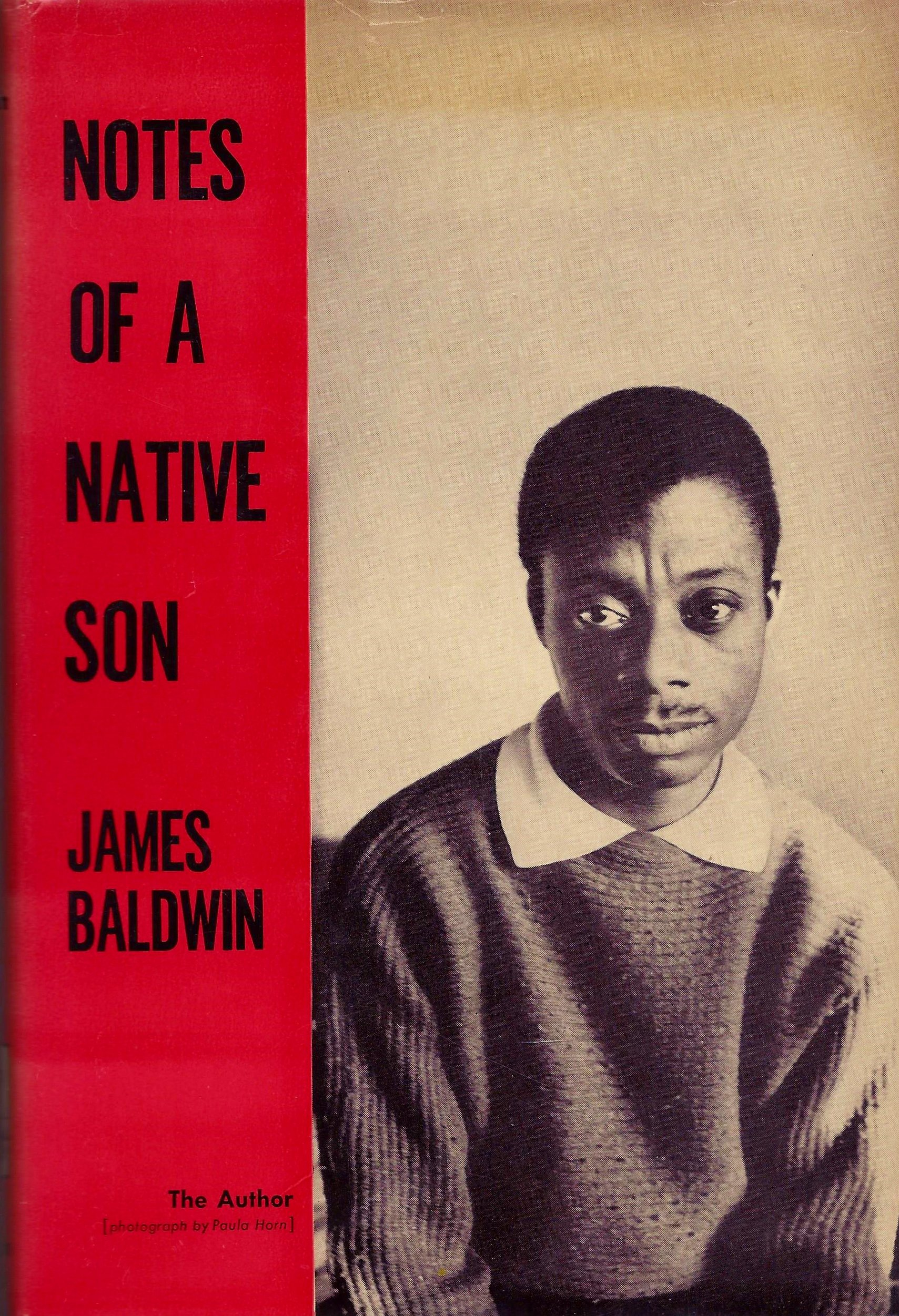

Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin

“From all available evidence no black man had ever set foot in this tiny Swiss village before I came.” This opening line from one of the essays collected in James Baldwin’s classic instantly turns most Western travel writing on its head. His observations of America and Europe are exhilarating and disturbing, and trying to see through his eyes becomes something like learning to pray—a practice, a dedication to understanding oneself and others through more than merely physical senses. Baldwin doesn’t even need to leave his home in Harlem to achieve that rare chemicalization—that churning of the mind—that other writers must travel years to achieve.

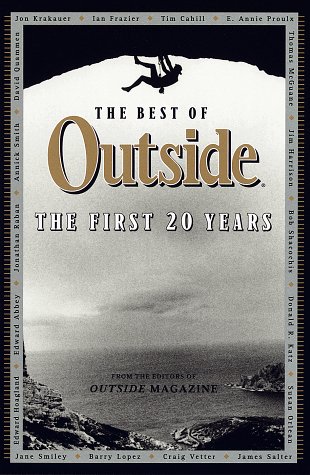

The Best of Outside: The First 20 Years by Selected Authors

This is a collection of writing from Outside magazine that nods to a particular high point in American travel writing: when the genre was very good, and also very full of itself. You learn as much about wandering as you do about that era, a time before selfies, mostly before the Internet, and definitely before many Western travelers really seemed to understand how they were moving through the world, and what they were leaving in their wakes. Here, Annie Proulx wanders the deserts of the West, Thomas McGuane writes exceedingly seriously about hunting, and Donald Katz (yes, the founder of Audible) goes in search of men who stuff ferrets down their pants.

Selected Translations by W.S. Merwin

Merwin was a decorated poet and a disciple of landscapes. But he may have done his best work when he hauled other poets—the long dead, the forgotten, the foreign—into the light. In this book, Merwin translates poets from ancient China and Egypt, South America, medieval Spain, and modern Russia into vivid, elegant English. In this way he travels more widely through time, space, and human desire than any other writer.

Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight by Alexandra Fuller

It’s an open question whether white people should write about Africa. But they do, and they will, and the answer won’t be settled soon. So selecting which white voices we open ourselves to requires care. Fuller was raised in Africa, so her perspective in this memoir diverges significantly from any visiting writer’s (I include myself in this category). Her family tale of struggle, particularly in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) during that country’s revolution (a revolution the colonizers ultimately lose) is fascinating, terrifying, and confounding.

Narrow Road to the Interior by Matsuo Basho

Matsuo Bashō is the poet most people hold responsible for haiku. He didn’t invent the form, but he did make it unforgettable. Some of his best-known work comes from this small book, written during a 17th-century trip from Edo (now called Tokyo) into the wild interior of Japan. But this travel account is not only comprised of poetry; Bashō also narrates his journey of more than 1,500 miles in spare, compelling prose. In many ways, his is the archetypal road trip. Hundreds of years ago, he was doing the thing we modern people long for after spending too much time on social media: selling his house and surrendering himself to the danger, privation, creativity, and spiritual refreshment of the path.

The Histories by Herodotus

Flying serpents, deserts full of bones, palace intrigues, wars, rumors of wars, wisdom, and folly. This book is time travel; it teaches you to sit still and listen. Whoever reads Herodotus as “history” is missing the point. He is a flying drone outfitted with a powerful camera, soaring over the ancient world of the Greeks and the Persians. He is the soil from which so many other works have sprung. And the details he recorded—true, false, or both—have become part of our DNA. Like other classics (the Odyssey, the Epic of Gilgamesh) a reader in our troubled times can open the book to almost any page and find a kind of ancient calm: humans, our ancestors, have come this way before.

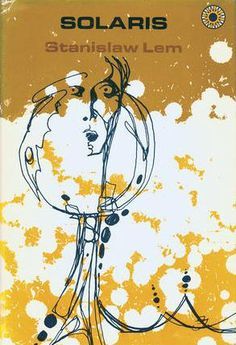

Solaris by Stanlislaw Lem

This is a novel of science fiction that delivers the reader to a faraway planet where scientists are attempting to communicate with a non-human entity. If this sounds at all familiar, please believe me when I tell you it is not. Once you reach the space station where the novel is set, you’ll never look back at Earth—or human communication—in quite the same way. And remember, the novel barely resembles any of the three movies based on it.