Tales From an Attic

Suitcases once belonging to residents of a New York State mental hospital tell the stories of long-forgotten lives

1.

In February 1995, New York Governor George Pataki announced plans to close the Willard Asylum for the Insane, a state-run institution that opened in 1869 on the eastern shore of Seneca Lake. Portions of the hospital would be converted into a drug treatment center for prisoners; the rest would be permanently shuttered. Before this could happen, however, the hospital’s many artifacts—for example, its 19th-century medical equipmenat—needed to be documented and preserved. This is what Craig Williams, then a curator at the New York State Museum in Albany, did for much of the spring of 1995. One morning that April, Beverly Courtwright, a longtime storehouse clerk at Willard, told Williams that he needed to see something. She took him to the deteriorated brick structure that once housed Willard’s medical labs and occupational therapy rooms. Together they went up several flights of stairs to the attic, an open loft with exposed wood rafters and a brick wall at one end. In the brick wall was a door. Courtwright didn’t open it, so Williams went through alone.

On the other side was a large room. Broken windows and holes in the roof made columns of light out of floating dust. Lining the perimeter were rough-hewn wood shelves speckled with pigeon droppings, and on these shelves were hundreds of old suitcases, each with a handwritten tag bearing a patient’s name and date of admittance. Williams called his supervisors in Albany, asking what he ought to do. Because New York State law allowed for the transfer of property from one state entity to another, the museum could take possession of any or all of the suitcases. Williams’s supervisors told him to keep a small sample—10 suitcases at most—for archiving, and to destroy the rest. But Williams couldn’t countenance that. He decided to save them all.

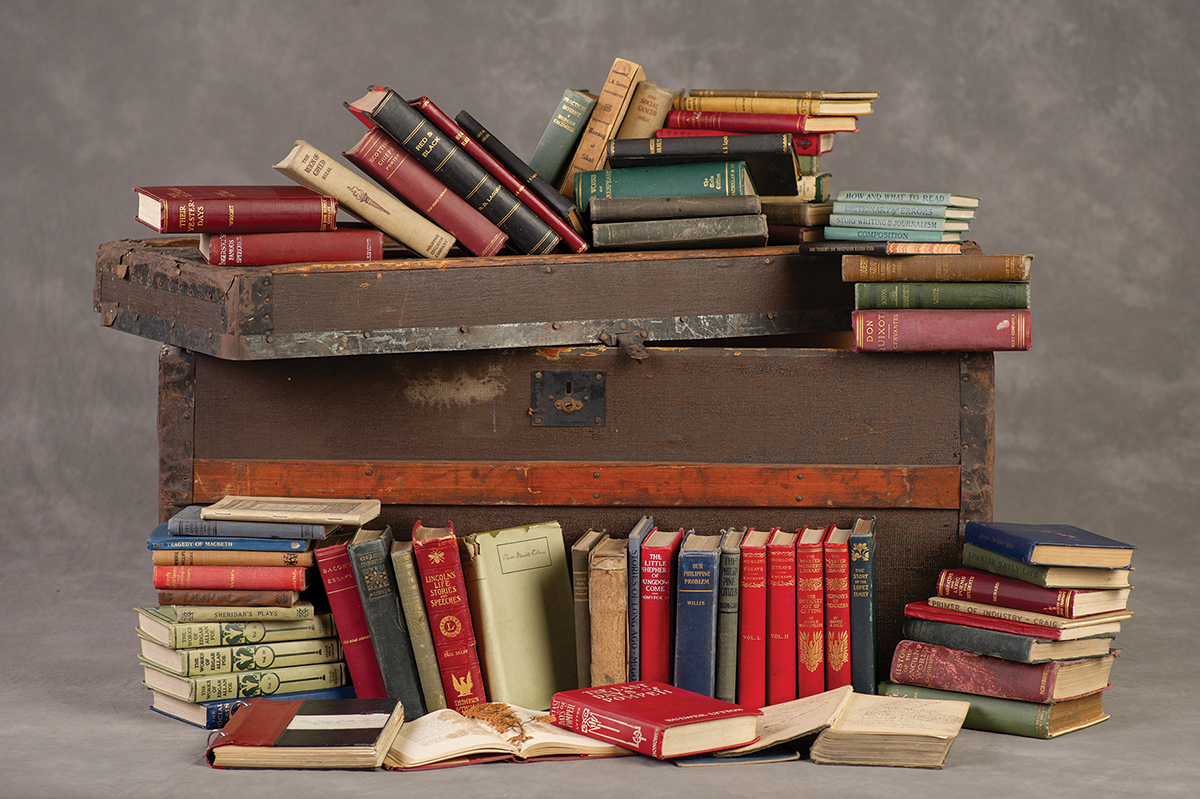

He returned to the attic a few days later and, with the help of some former Willard employees, wrapped the suitcases in cloth and readied them for transport. A few elderly patients were still living at Willard, awaiting transfer to other institutions, and their suitcases were returned to them. The rest—427 containers, not just suitcases but also trunks, crates, and doctor’s bags—were then sent from the Willard campus to the New York State Museum’s warehouse in Rotterdam, just outside Albany. There, volunteers and interns catalogued the contents of a few cases, but most remained unopened.

A few years later, as New York considered closing more hospitals and asylums, Williams met with the executive staff of the Commissioner of the State’s Office of Mental Health to discuss how the museum might better preserve the history of the state’s mental health treatment facilities. When he displayed images of a few of the Willard suitcases, Darby Penney, the head of the Office of Recipient Affairs, gasped. She and her colleague Peter Stastny, a psychiatrist, began working with Williams to review the contents of the suitcases and match a few of them with the medical records of the patients to whom they belonged.

In 2004, the exhibition “Lost Cases, Recovered Lives” opened at the New York State Museum, structured around a dozen of the Willard suitcases. “Much has been learned about the suitcase owners and the history of the New York State mental health system,” the museum stated at the time. “Curators hope their stories will restore a human dimension to a group of people who have been hidden and forgotten.” “Lost Cases, Recovered Lives” ran for nearly a year and inspired a traveling exhibition that toured for a decade. Penney and Stastny later published a book, The Lives They Left Behind, which told the stories of 10 patients whose possessions had been in the attic. Their last names were changed in accordance with confidentiality laws.

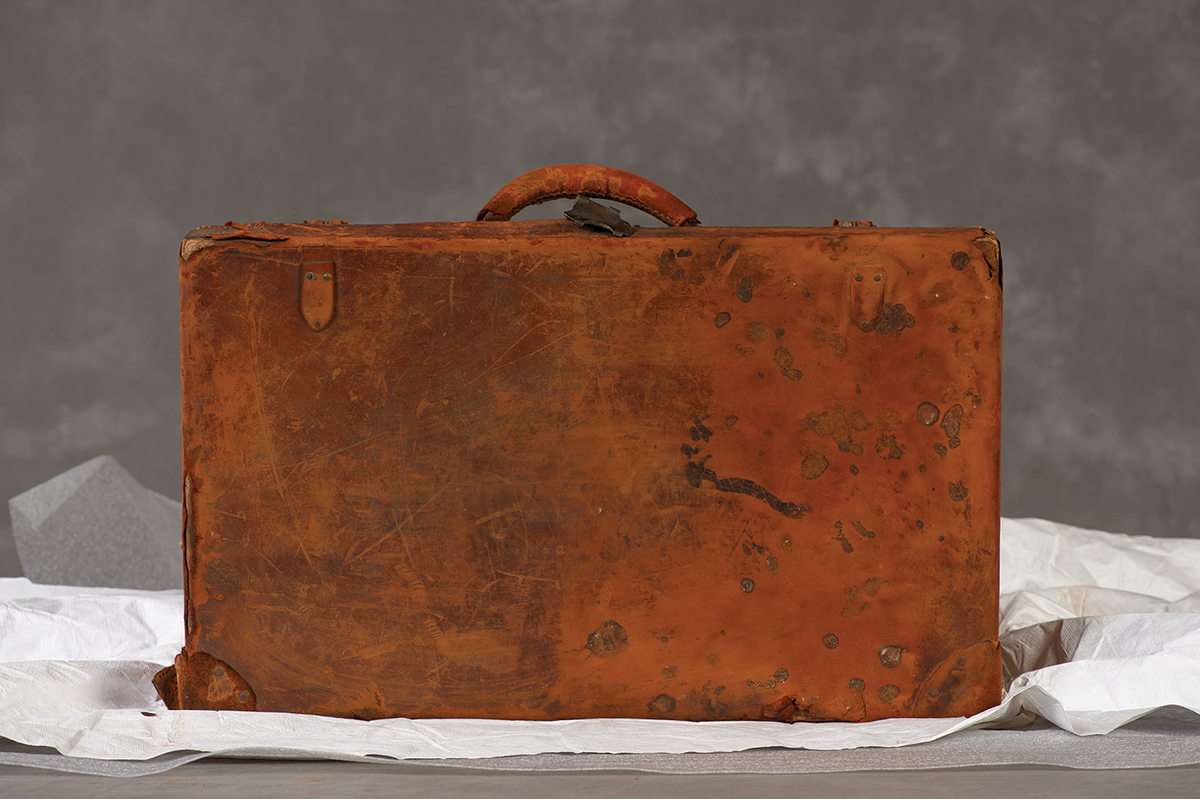

In 2011, Williams granted photographer Jon Crispin access to the Rotterdam warehouse—another way, Williams thought, to preserve the cases and their contents. The first one that Crispin unwrapped belonged to a patient known as Freda B. Mold bloomed on its leather exterior; the interior had cream-colored lining and matching straps that secured a jade-green Bakelite vanity set. The case also contained a yellow alarm clock, a box of Whittemore’s shoe cream, and a book for teachers called Primary Seat Work: Sense Training and Games.

Crispin and his assistant, Peggy Ross, had planned to photograph only a few of the cases. The more they worked, however, the stronger the instinct became to capture every single one. Crispin launched a few successful crowdfunding campaigns to support his work and posted photos online. He had access to the patients’ full names, but in the interests of privacy, he made every effort to conceal their identities. Some cases held addressed envelopes, library call slips, bank statements, and other identifying items. Crispin photoshopped surnames out of every image, leaving only first names and last initials. The blank spots where a surname had been were made to look like the weave of fabric, or the warm ivory color of old paper, or whatever was characteristic of the object’s surface. He added the full names of patients to the metadata of the digital photos in his personal archive, but he made sure to remove those names before posting them online. As he said in a 2012 interview published on the website Collectors Weekly:

I’m still trying to figure out how I can name these people, because I think it dehumanizes them even more not to. People who’ve been in mental institutions themselves have said, “Your project is very moving to me, but I’m very disappointed that you have to obscure names.” I think the stigma of mental illness has evolved from something shameful to something that’s much more medical and much more accepted. It just happens to people. But I’ve been very careful at this point in obscuring names. … I’m not showing their medical records; I’m only talking about the fact that they lived at Willard.

Crispin eventually photographed all 427 cases—an effort that took him six years. It now appears that other artists may not have that opportunity again. In 2014, the New York State Museum became aware of what it has since termed “significant questions of ownership” regarding the suitcases; work needed to be done, in conjunction with the New York State Office of Mental Health, to clear up issues related to title. In the meantime, the suitcases would remain in storage, inaccessible to researchers or those wishing to photograph or exhibit them. When I emailed the museum in January, asking about the status of the collection, a representative said that the museum “had determined that the suitcases and their contents are personal property” and are no longer considered property of the state. The guidelines for state property transfers, moreover, had changed since the museum’s acquisition of the Willard suitcases in the mid-’90s. “The collection will remain closed until we can determine who owns each suitcase and ask them to donate it to the New York State Museum,” the representative wrote. For Crispin, preventing access to the suitcases feels like a grave injustice. He feels a responsibility to the former owners of the suitcases to keep them in the public imagination. And he wants other artists to feel the same.

My interest in this story dates to May 2021, when I saw a few of Crispin’s photographs on his website. (Crispin has, from the beginning, owned the copyright to the images, allowing him to exhibit them.) Afterward, a friend of his put us in touch, and Crispin sent me links to more of his images. I was especially stirred by one of them, a photo depicting a brush and a pad of shaving soap in a round dish. I felt a certain intimacy with the owner of these objects, as if I were looking through a window at a stranger who assumed he was unobserved. The photograph was a revelation: whereas I had previously imagined life in a psychiatric hospital to be filled with moments of high drama and suffering, I had not considered the quotidian aspects. I began to imagine the human being who had once used these objects to shave every morning, and I found myself remembering a similar brush that my grandfather had kept beside his bathroom sink. I wanted to see more. I wanted to know more about the lives of this man and all those other patients.

Crispin later told me that he’d been receiving regular emails from descendants of Willard residents. They had seen the photographs and wanted more information, hoping that one of the suitcases might have belonged to a relative. Crispin said that he was talking to a law firm about possible legal action to force the museum to allow public access again. “For a long time, I thought that if I was cooperative and nice about it, they’d understand why this collection matters and open it again,” he said. “But now I want to stick my head above the parapet.”

Frank C., a U.S. Army veteran, was admitted to Willard in 1946, at the age of 35. Following a single outburst at a restaurant in Flatbush, Brooklyn, he was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. (Photograph by Jon Crispin)

2.

The Willard Asylum for the Insane was once one of the largest psychiatric hospitals in the United States, noted for its sprawling campus filled with shade trees, evergreens, generous lawns, and substantial Victorian buildings. It had a bowling alley, a theater that showed movies on Monday nights, a golf course, and a gymnasium. Many of its facilities were open to the public; residents who lived in the adjacent community of Ovid could watch a movie or play a round of golf. The local newspaper included a regular section that covered social events held at Willard—attended by both patients and people from the community. The hospital also ran a working farm, with patients growing crops, tending orchards and gardens, and raising cows, pigs, and chickens. At other asylums, patients were confined indoors. At Willard, doctors believed that patients benefited from work and fresh air. Not that they only worked outdoors: in the sewing room and tailor shop, patients made aprons, nightgowns, and chemises as well as the uniforms worn by nurses and orderlies.

In 1960, the State of New York made it illegal for patients to work without pay, thus curtailing agricultural production at Willard. On October 31, 1963, President Kennedy signed the Community Mental Health Act, which aimed to transition patients from state hospitals to outpatient care in communities. A human rights movement for people with mental illness brought scrutiny to poor conditions in state hospitals all over the country, the suffering caused by involuntary hospitalization, and treatment methods such as electroconvulsive therapy and psychosurgery.

In 1975, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a state couldn’t confine to a mental hospital anyone who could safely live in the community. Medicaid, introduced in 1965, offered some federal funding for outpatient mental health care, creating an incentive to move patients out of state-funded hospitals. In 1955, more than 93,000 patients lived in New York State mental hospitals. By 1994, that number had declined to fewer than 12,000. The state threatened to close Willard several times before Governor Pataki announced that the hospital would finally shut. During its 126 years of operation, about 54,000 people lived at Willard. More than a third of the hospital’s total population died there, and many patients were buried in the on-site cemetery. In the interests of privacy, their graves were marked not with names but with numbers.

This is why the suitcases are so important—even a few scant objects can vividly summon forth a forgotten life. Crispin’s photographs reveal many such lives in miniature:

A green trunk that belonged to Frank C. holds his military uniform as well as a studio portrait of a handsome Black man with high cheekbones wearing the same uniform. There are war ration books. Letters from the War Department sent to an address on Bainbridge Street, in Brooklyn. A handwritten note on lined paper bearing the date of Frank C.’s military discharge. A deposit book for an account at the Dime Savings Bank of Brooklyn.

Rodrigo L.’s trunk is full of books: The Last Days of Pompeii, Don Quixote, a three-volume collection of the works of Edgar Allan Poe. A handwritten manuscript authored by Rodrigo L. called “The Days of the Students.” The typed constitution and bylaws of the Filipino Working Men’s Club in Cheyenne, Wyoming. A book in Tagalog. Leaves, flowers, and dragonflies pressed between the pages of some of the books.

The trunk of Madeline C. unfolds into a wardrobe with drawers and a rack for hangers. Inside, a library call slip from 1929 for a book by Sigmund Freud. Principles of Psychology, volumes one and two, by William James. An address book filled with spiky cursive writing. Snapshots of Madeline C., elegantly dressed, her hair cropped stylishly short, in New York City, California, Canada, and Europe. A picture in which she wears a fur stole in front of a mansion, a large dog at her knee. Snapshots of the seashore taken from aboard a boat, many of the photographs labeled in French.

Benjamin M.’s suitcase holds only a toothpick.

History is preserved selectively and is subject to the same discriminatory biases that pervade culture at large. The homes of presidents become museums. The lives of illustrious scientists are documented in biographies. The papers of intellectuals and artists are sheltered in university archives. People who are culturally devalued or oppressed, meanwhile, are often excluded, in part or in whole, according to biased notions of their worth—a selective calculus determined by those who document lives for posterity. “Sometimes stories are destroyed,” Carmen Maria Machado writes in her memoir In the Dream House, “and sometimes they are never uttered in the first place.”

Historically, most writing about mental illness has been in service of understanding and documenting the illnesses themselves; the people who had them were routinely obscured. Freud used pseudonyms—“Wolf Man,” “Rat Man,” “Little Hans”—in his case histories; in Awakenings, Oliver Sacks identified patients with encephalitis lethargica by their first names and last initials. A woman known only as “Augustine” was admitted in 1875 to the Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris, where she was exhibited to curious members of the public to demonstrate neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot’s theories about hysteria. Charcot also photographed her, as he did other hospital residents, and his portraits were published in a book now in the collection of the Getty Museum. She is not named, only identified as hysterical and epileptic; photos purport to show her in both “normal” and hysterical states.

The firsthand experiences of people who lived as patients in psychiatric institutions are largely missing from the historical record. “The history of mental health is almost always told by psychiatrists and hardly ever by patients or through patients’ lives, so [the existence of the Willard suitcases] is pretty amazing,” Darby Penney told The New York Times in 2007. The intimacy of the personal items, the author of that article wrote, “helped rescue these individuals from the dark sprawl of anonymity.”

The uncoupling of illness from other parts of a patient’s identity was intended to protect privacy, not erase personhood. But when this happened to a whole group of people, especially those whose personhood was undervalued or under attack in the first place, erasure was the inevitable outcome.

Born in 1908, Freda B. was admitted to Willard in 1932, following episodes of screaming in public. She was a single woman and a schoolteacher. (Photograph by Jon Crispin)

3.

In September 2021, I traveled to Springfield, Massachusetts, where Jon Crispin met me at the train station. He was easy to recognize, even with an infinity scarf covering his nose and mouth. He was tall, dressed in slim-cut gray jeans, and he wore his silver hair a little long. As we drove to his home in Pelham, near Amherst, he told me about the first time he visited the Willard grounds. This was in 1982, following a wedding. He didn’t enter the property that day, but he was captivated by the sight of Chapin House—the hospital’s main building, which had been constructed in 1872. He wrote to Willard’s director, Anthony Mustille, asking permission to enter the building and take photographs, but his request was denied. A year later, however, Chapin House was scheduled for demolition, and Michael Labate, director of capital operations at the New York State Office of Mental Health, called Crispin, having heard that the photographer wanted to take pictures. “He said that if I wanted to get in,” Crispin told me, “I had better hurry.”

On his first day, two security guards escorted him through a side door. The wards of Chapin House looked like they had been abandoned quickly. Binders of papers were strewn over the floor. Drawers and cabinet doors had been left open. Paint peeled in long strips from the walls and ceilings; the exposed plaster was dark with mold. An upright piano with an exposed soundboard stood next to a window. One photograph Crispin took that day, in a wide corridor, evokes the wreckage of a ship. The light has a cool, underwater quality, time having corroded a once-grand interior as thoroughly as saltwater.

Crispin returned to Willard again and again. One day, while setting up his camera outside, Crispin ducked under a dark cloth to check the focus on the ground glass, then emerged to discover an older man standing nearby, watching him work. The man said that he lived at Willard and began describing what life was like at the hospital. “There used to be a lot of screaming,” he told Crispin. “But since psychotropic drugs were introduced, it has been nice. Quiet.”

Crispin continued to tell me about his experiences during dinner that evening—we were joined by his wife, Cris, and their son, Peter. Afterward, I got a tour of Crispin’s basement studio space. An old darkroom was piled high with large photographic prints, slides, boxes of negatives, and hard drives. On one wall was a list of Willard suitcase photographs that Crispin was printing and framing for an upcoming exhibition in Rochester. I glimpsed several other examples of his work: photographs of abandoned buildings, rural poverty, boats in the Erie Canal—all connected, in some way or other, to ideas of transience.

The following day, we made the 300-mile drive to Willard. As we entered the campus grounds, Crispin pointed out the buildings that now house the drug treatment program for prisoners, located behind forbidding metal fencing. Most of the campus was off-limits, the exception being the Romulus Historical Society, a two-story museum of Willard’s history located in the former house of the chief engineer.

When we arrived, Peggy Ellsworth, a former Willard nurse who runs the museum, had just turned on the lights, opened the window shades, and turned on the water. In what was once the living room, paint was coming off the ceiling in sheets above a large table that held a few binders of documents and photographs. Along the walls were various objects on display, accompanied by printed descriptions. A “strong dress” from the 1890s was hung next to a card explaining that it was used to calm agitated patients. When I touched it, the gingham fabric was heavy in my hand.

Pointing to a bulky wood chair with generous armrests, Ellsworth said, “That was made here. There would have been restraints on the armrests, and it is very heavy so you couldn’t knock it over and get hurt.”

Now in her 70s, she had the cheerful, practical manner of a longtime nurse. She gestured at a mannequin wearing a midcentury nurse’s uniform with a dark blue wool cape. “The cape is mine,” she said. “You’ll see my name written in the tag if you look.”

Ellsworth told me that she grew up in Ovid and remembers watching movies at Willard as a child. “The town and the hospital were very interconnected,” she said. Like other state psychiatric hospitals, Willard had a nursing school, from which Ellsworth graduated in 1969 before starting her career at the facility.

We sat at the large table, and I flipped through the binders, looking at photographs of Chapin House being torn down, dust rising from the debris. While I spoke with Ellsworth, Crispin sorted through a stack of local newspapers from the 1960s, occasionally photographing a page. “At the end, most of the patients who were still here were very old,” Ellsworth said. “They hadn’t lived outside of Willard for a long, long time.”

I asked her if she remembered any of the people whose suitcases were part of the state museum’s collection. I asked about Rodrigo L., the immigrant from the Philippines. “I would never have called him by his first name!” she said. “He was so formal. He always dressed in a suit. He moved away from Willard into the homes of people in the community a few times. But he was more comfortable here, so he always came back.”

And what did she feel when she looked at the suitcases?

Ellsworth pursed her lips. “At first, when I looked at them,” she said, “they seemed just like regular items that anyone would have. But later, sometimes they gave me new insight into a person I knew. Like Freda B. She was a tiny, very old, extremely quiet woman when I knew her. But when I saw her vanity set, there was something glamorous about it. It made me realize she might have been different before.”

Crispin took me to meet Terry Garahan, who had helped transfer patients from the hospital to community-care settings during the 1970s. After leaving Willard, he worked as a social worker and as a hostage negotiator for the FBI, performing threat assessments related to mental illness for several law enforcement agencies. “Garahan has seen the dark side of Willard,” Crispin said. He also had a master skeleton key for the hospital that Crispin wanted to photograph.

As we sat outside an Ithaca sandwich shop, Garahan showed us the large old-fashioned master key, laying it on the table. Garahan teased Crispin for being taken in by a romanticized version of life at Willard. “Peggy Ellsworth has a very sunny view,” he said. “She talks about Willard being a family. But people were put there against their will. They wanted to get out. They wanted to regain their freedom.”

Garahan said that he had seen staff members resort to violence as a way to deal with uncooperative patients. He also said that there existed, inside the hospital, an economy built around sexual favors. He saw suffering firsthand. “Patients had lost their human rights,” he said. “They had no agency in their own lives. That’s not any kind of family that I’d want to be part of.”

Rodrigo L.’s trunk contains not only a substantial library of volumes from Cervantes to Poe but also a manuscript that he wrote. (Photograph by Jon Crispin)

4.

In 2011, Lin Stuhler, a native of Rochester with a passion for genealogy, created a website containing census data from Willard along with other information she had gathered during her research into the hospital. At its height, her site received 60,000 visits a month. Most of the comments were from people looking for information about institutionalized family members:

He was shot in the face at the Battle of Cedar Mountain and it is theorized that this caused him to have mental health issues.

My g.g. grandmother was a patient at Willard Asylum intermittently from 1876 until her death in 1893. I believe she is buried there. I would love to find out more about her and what put her there.

My mother was hospitalized at WPC most of my childhood. We met for the first time in the Chapin Bldg., age eight.

Stuhler responded to many requests with information on how to get records from cemeteries or how to find a name in a census. But she mostly had to explain that New York doesn’t release records pertaining to people buried in the cemeteries of state psychiatric hospitals. The majority of the people who had found Stuhler’s website reached an archival dead end.

In 2001, Stuhler tracked down an online obituary for her great-grandmother Margaret Putnam, who had died at Willard in 1928. After learning about the suitcases some years later, she wrote to Darby Penney and asked if her grandmother’s possessions were among them. They were not.

It was Penney who informed Stuhler that state hospital patients without family were buried in anonymous graves, which Stuhler felt was “extremely cruel.” According to her obituary, her great-grandmother had been buried in Lake View Cemetery in Jamestown, New York, with her family holding a funeral service. It was wrong, Stuhler felt, that thousands of other patients were denied that dignity.

Stuhler researched Willard for more than a decade in a quest to learn about her own family and to help others with similar questions. “You can’t get medical records about your own ancestors unless a physician says that it is necessary to your health,” she explained to me. Stuhler has essential tremor, a neurological disorder that is often genetic. In 2007, she and her doctor submitted to the state a records request for her great-grandmother, arguing that the information was relevant to the understanding and treatment of Stuhler’s neurological disorder. Seven months later, she got a letter informing her that Margaret Putnam’s file couldn’t be located. Stuhler continued to make requests and write letters to elected officials as well as the state’s Office of Mental Health. In 2011, she received this response from the commissioner of that office, Michael F. Hogan:

The family members of the individuals buried at Willard may or may not want their relative with mental illness recognized. Even relatives would have no right to the information unless their primary care physician needed the health records to diagnose or treat a condition. I would also remind you that the penalties for violations are very stiff—civil penalties under the federal law can carry up to $10,000 per violation.

A friend of Stuhler’s emailed her a bill that had been passed in Washington State in 2004. It allowed for the release of psychiatric patients’ names for the purpose of constructing memorials. Stuhler shared it with the chief of staff of her state senator, Joseph Robach, who in 2012 introduced a bill in the New York State Legislature that would have authorized the release of patient names, death dates, and grave locations to the public. The bill did not pass. A second attempt followed in 2015, but the terms were changed so that names could be released only to a special cemetery project group—a legal entity that, Stuhler said, was complicated and costly to set up. This bill passed, but its passage didn’t help Stuhler, who wept in frustration.

When I talked to her on the phone, she seemed defeated. “I would really like to a have a photograph of my great-grandmother,” she says. Medical records at Willard often included a photograph of the patient. “And knowing that it exists, but I can’t see it, is just so frustrating.”

Colleen Spellecy, a retired schoolteacher in Waterloo, New York, about 15 miles from Ovid, became interested in the Willard story when she read about a patient named Lawrence M., who dug graves at the hospital cemetery. His suitcase contained shaving mugs and brushes, suspenders, and black dress shoes made before World War I. He was buried somewhere in the Willard cemetery under a numbered marker.

Spellecy and other volunteers created the Willard Cemetery Memorial Project to advocate for the recognition of people like him. Born in Austro-Hungarian Galicia in 1878, Lawrence M. served in the military before emigrating to the United States and getting a job at Bellevue Hospital in New York City. Arriving at Willard in 1918, he lived in a shack in the middle of the 29-acre cemetery during the warmer months. Spellecy’s group wanted to place a memorial plaque on the site. The New York Office of Mental Health objected, however, again citing patient privacy concerns. Spellecy felt that acknowledging at least one patient buried at Willard was a symbolic gesture of respect to the rest of the anonymous patients buried there.

In December 2014, after The New York Times published an article about the conflict between the Willard Cemetery Memorial Project and the Office of Mental Health, Spellecy got a letter saying that a relative of Lawrence M.’s had been found and had given consent for a memorial. This is how Lawrence M. regained his full name: Lawrence Mocha.

Crispin attended a ceremony for the unveiling of the memorial in May 2015. A large crowd gathered under a big white tent as a minister blessed the memorial stone. “They say you die twice,” he recited. “One time when you stop breathing and a second time, when no one speaks your name.” Crispin kept the memorial card and pinned it to the wall in his basement studio.

5.

“There are two broad justifications for the privacy of medical information,” Paul Appelbaum, a psychiatrist and an expert on legal and ethical issues in the field, told me. “One is utilitarian: without privacy, people might not tell their doctors about their symptoms, their sex lives, their drug use, or other material information that is necessary for diagnosis and treatment—if not forgo treatment entirely.”

The other justification, he says, is ontological. Cultures have historically recognized that individuals should control their own intimate, personal information. The Hippocratic Oath has a privacy clause, under which physicians acknowledge that a patient’s problems “are not disclosed to me that the world may know.” The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) became federal law in 1996 to protect the sensitive health information of patients. And the HIPAA Privacy Rule, issued by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, has provided uniform statutory protection of medical information, including after a person’s death. Those protections can be especially robust when they concern a patient’s psychiatric diagnosis and treatment—details “considered even more personal, and more likely to lead to stigma and discrimination than other kinds of medical information,” Appelbaum said. “So many states have regulations and statutes that go above and beyond HIPAA to provide special protections for mental health information.”

At what point, then, does historical interest matter more than individual privacy? There isn’t always a clear line, Appelbaum said, and when it does exist, it can appear arbitrarily drawn. The Presidential Records Act requires that White House documents be kept secret for five years before they become subject to Freedom of Information Act requests, with some records withheld even longer. The National Archives holds records for the decennial census for 72 years. “If we found a trove of medical records from ancient Greece, it would certainly be used by scholars, journalists, and the public to learn about both medicine and life 2,400 years ago,” Appelbaum said. “But if you wanted to read the medical records of someone who died 10 years ago, their family would likely feel that was an inappropriate invasion of privacy.” Would it feel more appropriate after 50 years? After 100?

Appelbaum and I talked about how the medical history of one’s ancestors has become increasingly relevant the more we learn about the genetic determinants of diseases. (I was thinking of Stuhler and her essential tremor.) Appelbaum mentioned how many of the famous patients of the late 19th and early 20th centuries are now known. Freud’s “Little Hans” was the son of Viennese music critic Max Graf. “Wolf Man” was Sergei Pankejeff, a Russian aristocrat. “Rat Man” was an Austrian lawyer named Ernst Lanzer who died serving in World War I. “There is an argument that we can confer dignity by recovering history, by providing names to unmarked graves,” Appelbaum said. “That is a legitimate consideration that must also be balanced against the desire of some families that their personal histories not become public knowledge.”

Madeline C.’s trunk contains works by Freud and William James as well as numerous photographs depicting an elegantly dressed and stylish world traveler. (Photograph by Jon Crispin)

6.

I wanted to talk to Craig Williams, whose discovery of the Willard suitcases in 1995—while he was a curator of photography at the New York State Museum—set in motion a series of events that would last a quarter century. A few days after I visited Willard, we met at Taughannock Falls, a popular attraction outside Ithaca. We sat on a low wall where tourists took in the view of the high, thin waterfall. In a soft voice that compelled me to bend toward him as he spoke, he told me about that day when Beverly Courtwright led him up to that attic. “She wasn’t sure if the suitcases should be shared with the world—that’s why she didn’t open the door,” he said. “She’s very sensitive to other people. She thought maybe it would be better to let them disappear when the building was demolished.”

Williams made a pained expression and adjusted his glasses. “She came to the exhibit of the suitcases in Albany, and she said that the people, the suitcase people, would have been happy with what we’d done.” But when she saw another exhibition at the museum, devoted to 9/11, Courtwright told him that “the people who had perished would not have liked those artifacts to be displayed.” There were tears in Williams’s eyes that he blinked away.

He told me that Willard administrators kept a ledger, a code key that linked the names of those buried in its cemetery to the numbers marking the plots. When Willard closed, Williams found the ledger, and he took it to the New York State Archives. “I kept having this nagging thought that if I was in a fiery crash, I had the only copy of the ledger,” he said. “If it was lost, no one would ever know who was laid to rest in which grave.”

The suitcases, Williams said, provided only a tiny glimpse into the lives of their owners. A hint. He felt that much of the emotional force experienced by viewers came from the viewers themselves. Because the suitcases function like art, he said, they spark imaginative, empathic responses in those who look at them. And this is why they function so fruitfully as source material. Composer Julianne Wick Davis discovered the collection online and was inspired to compose a song cycle. English choreographer Michael Heatley created a dance performance. Karen Miller, a poet and psychiatrist, wrote verse. Amherst College professor Ilan Stavans wrote a speculative nonfiction book about the suitcase belonging to Charles F.

I considered the contents of my purse, which was on the ground next to me. A grocery store loyalty card. Proof of Covid vaccination. A pair of cut-glass earrings that I’d worn as a bridesmaid several years ago. What might a stranger learn about me from these things? Probably not much. But then, looking at the families and groups of older people gazing at the waterfall, I wondered: What if all the handbags and backpacks belonging to the people visiting Taughannock Falls that day could be collected and examined? What could be gleaned about our lives on that September day in the middle of a global pandemic? If later generations found that assemblage in an attic one day, what could be learned about how we lived?

7.

I met with Karen Miller in the basement office of her home in Amherst, Massachusetts. Miller, who had hair cut to her chin and a composed, upright posture, was freshly retired from her career as a psychiatrist in Boston. The way we were positioned—facing each other in a warm, quiet space—felt almost like I was in a therapy session. She told me that she had examined the suitcases in person and, because of her credentials as a psychiatrist, had been granted access to the medical records of the suitcase owners. Among these were accident reports and reports written by nursing staff when a patient ran away or was injured. Miller had also seen letters written by Willard patients. “In the ’30s and ’40s,” she said, “there was a great interest in psychoanalysis, which sometimes resulted in 10 or 15 pages of a transcribed interview that are very personal and vivid.”

I was jealous of her access, of her opportunity to see the suitcases and touch the paper that bore the handwriting of their owners. She’d had a more intimate relationship with them than I could ever hope for.

I had read Miller’s poetry and the text she’d written for a 2013 exhibition at the Exploratorium in San Francisco that featured a few of the suitcases along with Crispin’s photographs. Her writings were filled with the kind of poignant details that I wanted to know. For instance, how Flora T., a former nurse who was admitted in 1914, turned down the bedcovers of her fellow patients every night until her death in 1972. Many of the texts include the patients’ own words. “It was important to me to know what the people at Willard had to say about their own experience, to have them speak for themselves,” Miller said. “There is a vulnerability to being ill where you can’t hide what you think. People who can’t stop themselves from talking about their suffering have a lot to teach us, especially about what they need.”

She told me about Frank C., who was born in 1919 in West Virginia and moved to New York City to work as a chauffeur before joining the military. After he was discharged, he struggled to sustain himself financially. He described the incident that caused him to be institutionalized in a letter to a relative, either never sent or kept in duplicate: “I am not sick. I got excited on Fulton Street and I was throwing garbage. My blood temper. I was angry.”

Rodrigo L. was sent from the Philippines to be educated in the United States at the age of nine. He taught high school in Chicago before becoming a servant in upstate New York. When he was admitted to Willard in 1919, he had persistent delusions that he had sinned, and he heard accusatory voices. In 1921, he wrote a letter to his uncle with the postscript, “I have no definite knowledge yet when I shall obtain my freedom.” He died at Willard in 1981.

Madeline C. was a graduate of the Sorbonne, a single French woman of means who moved to the States to be a teacher. She sought help from psychiatrists while living in New York City. In one of her notebooks, she’d written in pencil, “Among superior intelligence, profound apathy is sometimes brought on by nothing more than a series of experiences whose climax is disillusionment and a disgust of life … a pattern of personality is shattered and out of the ruins rises an enfeebled and restricted spirit.” She had a reputation among staff for being difficult and was transferred from Willard in 1975, when she was almost 80.

Miller also wrote a poem about Freda B. that uses text from her medical records. In the poem, the question is raised, “When did it begin?” And Freda B. answers:

I didn’t do it very much.

I haven’t been doing that so much lately.

I am twenty-four now and I was teaching school until somebody—Because I guess it was

because of

masturbation.

Later, the interrogator asks, “Did you ever have sexual intercourse?” and Freda B. answers, “I almost did.” Toward the end of the poem, a few sentences from nursing staff about Freda B. are quoted: “She has persistently refused nourishment and was tube fed today. When not noisy she lies in bed with her eyes closed, indifferent to everything and everybody around her.” Then Freda B. speaks the last line: “I think I will be here all my life.”

Freda B. was born in 1908. She was admitted to Willard in 1932, discharged in 1933, and readmitted the following year. Miller said that her later records were missing. Freda B. was a single woman and a schoolteacher; her father was a principal whom she was afraid of shaming. In the months before her admission, she had episodes of screaming in public. At Willard, on more than one occasion, she removed her clothing and ran, terrified, until restrained.

Karen and I sat in silence for a few moments. Is this what I’d wanted to know? Usually, hearing of other people’s secrets and private lives held a special kind of pleasure. This, after all, is one reason why we read novels or listen to gossip: to experience an interior life other than our own. My fascination with the people who lived at Willard wasn’t without some salacious curiosity and an expectation that their lives, presumably more extreme, more vivid than mine, were worthy of art.

But from an ethical standpoint, was it right to transform into art the lives of those who suffered quietly for so many years? What was the cost to the patient when photographs were taken, poetry written, song cycles composed, magazine essays published? Was I taking narrative pleasure from Freda B.’s suffering? Or was Crispin right in his belief that the primary emotional relationship that most people feel when they look at the suitcases is empathy? And what to do with the fact that Freda B. herself had no choice in the decision to photograph her suitcase, to have her personal effects displayed for everyone to see?

Empathy was an aesthetic term before it was a psychological one. The German word Einfühlung was once used to describe the feeling of emotional resonance with a piece of art, of knowing it from within. In the early 20th century, English-speaking psychiatrists translated the word to empathy, expanding its meaning to include the sense of feeling one’s way into the experience of another. Psychologists long believed that empathy was an inborn, fixed trait. More recent research suggests that it is a competency that can be strengthened or weakened with experience or training. Meditation can increase empathy. So can reading novels.

My whole life, I’ve believed that all of us share a few essential desires, fears, and perceptual experiences of being human. Our differences, I’ve always thought, were the result of differing life circumstances, which shape our preferences, our style, and our narratives. I have persisted in this belief because it has allowed me to imagine the possibility that I could understand other people, that we could be decipherable to one another. Someone told me once that sharing your life with a partner is consolation for only being allowed to live one life. That when you know someone else intimately, when you participate in the daily joy and sadness that person feels, it is as close as you can come to living more than one life. It seems to me that we need that consolation many times over, in many forms.

Lawrence M. was born in Austro-Hungarian Galicia in 1878. After being admitted to Willard, he worked as a gravedigger at the hospital’s cemetery and lived in a shack on its grounds during the warmer months. (Photograph by Jon Crispin)

8.

A sign outside the Willard graveyard reads, “This cemetery was used from 1870 to 2000. Here laid to rest are 5,776 departed Willard patients.” When I visited with Crispin, the leaves were still green, the wild grasses nearly knee high, Seneca Lake visible through the branches of black walnut trees. I picked up fallen walnuts in their citrus-scented husks and dug my fingernails into their light green pulp, wondering whether Willard patients had once done the same.

“I’ve been told that the names of the patients were buried with them in small glass tubes sealed with wax,” Crispin said as we surveyed the clearing. Several paths had been mowed into the tall grass, but few grave markers were visible. There were some older ones, metal spikes with numbers etched into square tops, tangled among saplings. New circular aluminum markers were flush with the ground, installed so that a lawnmower could run over them. There were demarcations for Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish sections and, to my surprise, military sections with full names, wars fought, and dates of birth and death engraved on headstones. Someone had stuck American flags in the grass nearby, recently enough that the colors were true.

The memorial for Lawrence Mocha was a round boulder set atop a pile of light-colored gravel. A shovel handle stuck out of the gravel, and a plaque explained that in his 50 years at Willard, Mocha dug more than 1,500 graves. He wore hip waders while he worked because groundwater would fill the holes as he dug.

The cemetery felt to me like the Civil War battlefields I’ve visited, only there were no other tourists. I’d wanted to feel a connection to the past, smell a whiff of gunpowder. Instead, I’d found an empty field, the hum of insects. I’d felt so much more while looking at the photographs of the suitcases. The images of Freda B.’s belongings, for example, had induced in me a shiver of recognition—slender, tenuous, but electric, a bittersweet feeling akin to longing, a flickering sensation of shared humanity.

I asked Crispin if he felt a particular tenderness toward any of the suitcase owners. He said he often thinks about a photographer who’d been institutionalized because he had epilepsy. “My son has epilepsy,” Crispin said. “That story can bring a tear to my eye.” Crispin’s work is itself an act of empathy and imagination. Speaking the names of the dead so that they wouldn’t die twice. Imagining their interior lives, which had seemed unimaginable to many of their contemporaries.

Crispin asked if he could photograph me, make me a part of the story he was telling. I fixed Freda B. in my mind as I posed with my hands in my coat pockets, still clutching that walnut, its tannins staining my palm. She knew this lake. She’d heard this birdsong. There was evidence of her still, even if it was mostly inside my head.