The Book of All Books by Roberto Calasso (translated from the Italian by Tim Parks); Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 464 pp., $35

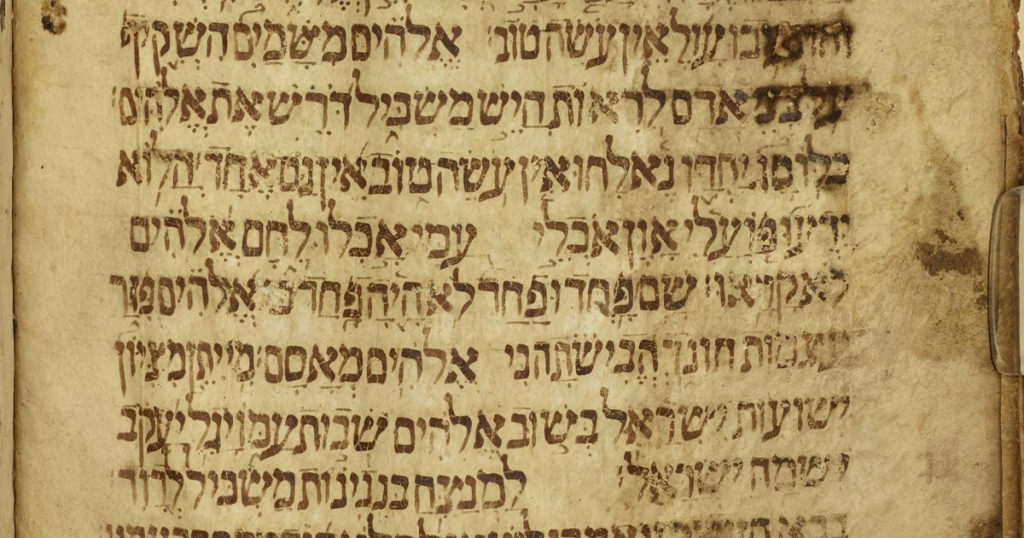

The venerable Italian publisher and writer Roberto Calasso passed away in July, at age 80. Called “a literary institution of one” by The Paris Review, he spent half of his life writing a series of esoteric books about the ancient forces that drive modern civilization, with works ranging in subject from Greek and Hindu mythology to Kafka to Baudelaire’s artistic circle. In The Book of All Books, the 10th installment in the series, Calasso turns to the Hebrew Bible, itself an anthology of books produced over the course of a millennium. Among and even within those books are anthologies of various sources, different versions of the same story stitched together to leave perplexing contradictory repetitions. Yet, as Calasso writes, “the Bible has no rivals when it comes to the art of omission, of not saying what everyone would like to know.” Why didn’t Cain’s offering please Yahweh? Why did Yahweh choose Abraham, or ask him to sacrifice his son Isaac? Why did Samuel choose Saul as Israel’s first king? Why does Yahweh try to kill Moses? We can never really know. But Calasso’s not interested in explanation so much as exploring the mysterious biblical narratives. He wants us, too, to “enter there as into a second world,” as Goethe wrote, “and lose ourselves there.”

Most people who read the Bible usually read selected passages, rather than go from beginning to end. Yet Calasso contends that “only by reading the Bible through can one weigh the omissions against the repetitions” and “grasp that unique phenomenon, so unlike any other, which is the Bible.” It’s odd, then, that rather than move through the Bible linearly, which would allow us to understand the intertextual narrative as “the unknown Final Redactor” intended it to be read, Calasso meanders haphazardly, jumping back and forth through the books. Why such a haphazard structure? It doesn’t make any sense—until you realize that Calasso is circling around the theme of sacrifice, something he hints at by employing the term “holocaust” instead of the usual “burnt offering.”

Calasso was fluent in Latin and Greek but not Hebrew, so I figured this tic was due to his reliance on the Vulgate and Septuagint, the Latin and Greek translations of the Bible. That is, I initially thought it was a mistake. But just after offensively referring to animals sacrificed during religious rituals as “holocaust victims,” he finally reveals what he’s getting at. The Greek word holókauston is a translation of the Hebrew olah: a religious sacrifice in which an animal is consumed by fire. Calasso laments the later use of the word Holocaust to designate the murder of six million Jews, as it granted the Nazis “an immense, quite undeserved honor,” indicating “they had been performing a ceaseless religious ceremony, while actually they were engaged in systematic killing.” His attempt to reclaim the word is perhaps misconceived, but by repeatedly returning to the act of sacrificing a burnt offering—from Noah’s olah on the altar he built after the Flood, to Abraham’s attempted sacrifice of Isaac, to the steady stream of blood running from the altar of the Temple in Jerusalem—Calasso reframes the Bible as a narrative of the transformation of ritual sacrifice, from prehistoric times to today.

Human sacrifice was an abomination, and many think the Binding of Isaac story represents the substitution of animal sacrifice, the detailed instructions for which take up much of the Book of Leviticus. But during the time of the prophets, Yahweh decided he had made a mistake with such commandments and, as the eighth-century BCE prophet Hosea explained, now wanted “mercy, not sacrifice; knowledge of God, not holocausts.” Fortunately, after the Second Temple was destroyed, no more sacrifices could be made, as the Temple in Jerusalem was the only place where the liturgy could be performed. This was a blow to the priests, who made their livelihood performing such bloody rituals, but a blessing to the rabbis. As Calasso asserts, the destruction of the temple forced the elimination of the “what of the sacrifice: the victims, the fire, the blood,” and replaced it with “recitation,” with a “pure mental gesture.” That is, the heir of the temple is not the synagogue, which is essentially a community meeting place, but the house of study, the yeshiva, where “the smoke of burned animals and the blood smeared on the four horns of the altar” is still offered in the scriptures. In other words, Torah study is the modernized, sanitized form of blood sacrifice.

Though intriguing, this take isn’t exactly revealing. After all, the Kabbalah phenomenon is based on a similar premise. And so, Calasso’s exploration through the Bible’s labyrinthine narratives is compelling but not necessarily illuminating. Ultimately, the stories are more perplexing than ever. Yet that’s to be expected. As biblical scholar Gerhard von Rad admits, “However much we attempt to enter into the story, we will never be able to make the incomprehensible comprehensible.”

But that’s the boon. Being confronted with perplexity, forced into a state of unknowing—that’s what great literature is all about.