When James Joyce and his family turned up in Paris in the summer of 1920, the writer had with him the sprawling manuscript-in-progress that would, by all accounts, become a landmark of modern literature. At a party where Ezra Pound was also a guest, Joyce met Sylvia Beach, an American in her early 30s and the proprietor of an English-language bookstore and lending library called Shakespeare and Company, located in Paris’s Latin Quarter. Beach had been looking to bring herself and her small business to the attention of the literary world, and in the figure of Joyce and his massive work called Ulysses, she immediately recognized the opportunity she had been waiting for—to do something extraordinary.

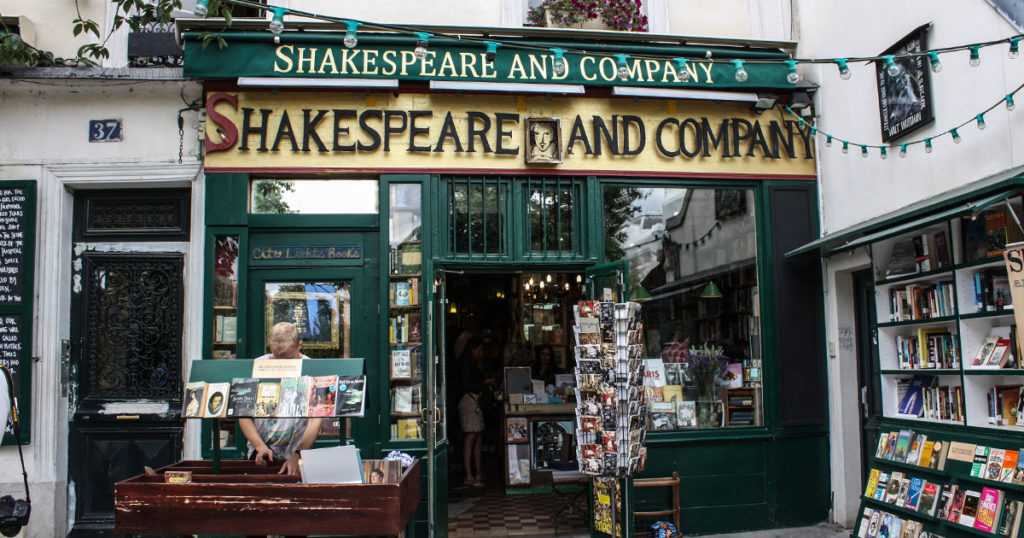

Beach was born in 1887 and grew up in a middle-class New Jersey family. Her father, Sylvester Beach, was a Princeton-educated Presbyterian minister whose congregants included two American presidents—Grover Cleveland and Woodrow Wilson. In this milieu Sylvia Beach and her two sisters learned to be discreet, to keep up appearances, and to be of service to others. Along the way, though, other influences intervened: her mother was a lover of music and the arts, and she instilled in the girls a deep respect for artists. Beach herself found her way to books, becoming passionate about poetry and experimental writing. She worked for the American Red Cross in Serbia at the end of the First World War, joining those like Edith Wharton and Gertrude Stein who had thrown themselves into the Allied relief efforts. She discovered Paris and her own sexual orientation when she fell in love with a French bookseller named Adrienne Monnier. It was Monnier, proprietor of the Left Bank bookstore La Maison des Amis des Livres, who mentored her into having a bookstore of her own. Shakespeare and Company soon became a cultural force. In the 1920s, Paris was thriving as a site for American expatriates, and Beach’s bookstore became its homeroom.

By the time Joyce showed Beach the manuscript of his brazen, boundary-pushing work, he had given up on the idea of finding a publisher in England or America. Joyce’s style was anything but ordinary, with each episode of the novel having a singular experimental approach (one was written in question-and-answer form, another in the tone of a romance novel). He insisted on pushing the boundaries of polite language, and in his desire to show all dimensions of life, including sex and scatology, he thrived on baiting the censors. Joyce was relentless in fighting for his right to use the words he wanted to use, however explicit, and to address the subjects he wanted to address, however beyond the norms of the late-Victorian society he grew up in. Because of the strict laws governing obscenity in England and the United States, many publishers weren’t willing to take the legal risk of printing works that could be deemed obscene. Between 1918 and 1920, Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, the American editors of The Little Review, published parts of Ulysses in serial form and were prosecuted for it. But the book industry in France operated under different conditions, and it was possible for Ulysses to appear there. Beach decided to publish Ulysses herself, under the imprint of her bookstore Shakespeare and Company. Had she not taken up the challenge, it’s possible that another Paris publisher may have been found—but it is unlikely that anyone else would have served the book as well as she did. She deeply loved Joyce’s masterwork, appreciating its daring linguistic experiments, its humor, and its humanistic core. With total conviction in the book’s importance, she faced every challenge that arose in bringing Ulysses into print, and they were manifold.

For one thing, Joyce was losing his eyesight during the time he was composing Ulysses and had to undergo several painful eye operations. Often, under these conditions, he could scarcely read; to keep track of the pages, he marked them up with bold colored crayons. Beach had to find typists who could help tame Joyce’s messy manuscript into something that could be typeset. With very limited funds, she needed someone who would agree to do the work first and get paid later. She found an amenable French printer named Maurice Darantière, but of course, his press was set up for printing books in French, and he had a hard time creating an accurate English-language text. Because of all these difficulties, not to mention the great length of the work, the first edition of Ulysses was full of errors. To raise the necessary funds, Beach also designed a subscription service, asking people to put up money in advance of the novel’s publication. She undertook a major campaign, trying to convince the public of the importance of the work. Many famous writers—including Stein, Pound, and André Gide—subscribed, though a few, most notably George Bernard Shaw, refused. Joyce’s fellow Irishman deemed the book “a revolting record of a disgusting phase of civilization,” though he also conceded that “it is a truthful one.”

Publishing Ulysses was hard enough, especially while trying to run a bookstore. Beach had plenty to do, including mentoring and supporting writers other than Joyce—Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Kay Boyle, H.D., and many more. But working with the famously difficult Joyce presented special challenges. The writer believed very strongly in his own genius and his right to call on the help of others to support it. Although diligent, he was also disorganized, melodramatic, and endless in his demands. Beach was the kind of person who had trouble establishing boundaries. And so, in addition to being his publisher, she provided a multitude of other services for him, acting as his secretary, banker, real estate agent, medical consultant, and more. When Joyce, his common-law wife, Nora, and their two children had initially arrived in Paris, Beach played a major role in getting the family settled. (Assistance also came from a wealthy patron, Harriet Shaw Weaver, who paid the family’s bills so that Joyce could write full time.)

When Ulysses appeared in 1922, just in time for Joyce’s 40th birthday, Beach could not have foreseen the battles still to come, including the piracy of the novel by the American publisher Samuel Roth, who produced a serialized version without Joyce’s or Beach’s permission; the hard times of the 1930s, when Shakespeare and Company nearly went out of business; and the blow that came when Joyce ultimately sold the rights for Ulysses to Random House without sharing any of the proceeds with Beach. But even though their relationship later became strained, Joyce recognized what he owed her, reflecting that “all she ever did was to make me a present of the ten best years of her life.”

Beach’s memoir Shakespeare and Company (1959) and her published letters give insight into the wit and whimsy of her personality, as well as the day-to-day business of publishing Ulysses and running her bookstore. She also appears as a character in some classic expatriate memoirs, such as Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast, Stein’s Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, and Being Geniuses Together, written by Boyle and Robert McAlmon—evidence of just how influential a figure she was. Moreover, the brilliant, insightful essays of Beach’s partner in life and books (collected in The Very Rich Hours of Adrienne Monnier) illuminate the French side of her life. Today, a century after the publication of Ulysses, Sylvia Beach remains a hero to many: she is the quintessential bookstore owner, independent publisher, and champion of literature’s freedom to experiment, challenge, and shock.