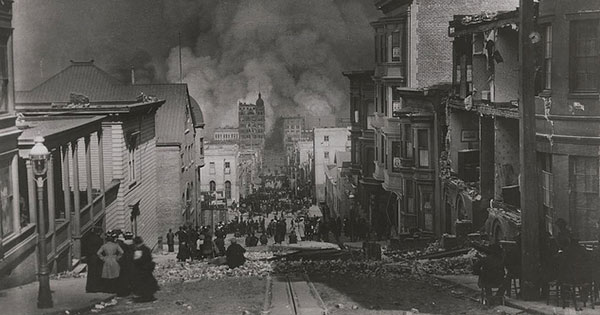

When I was in elementary school, my geography teacher showed the class a black and white photograph of San Francisco in flames. It was taken in 1906 after a violent earthquake, we were told. And thus began our lesson on earthquakes and the dangers thereof. As we sat there listening to tales of deaths and other horrors that befell the city, Miss Jenkins assured us that such a quake will certainly happen again. So why, I wondered, do people continue to live in San Francisco?

People’s perception of risk is only partly based on the statistical likelihood of an event occurring. A landmark 1989 review of risk by Paul Slovic concluded that people are much more worried about uncontrollable catastrophic events, such as a nuclear war, than statistically more likely ones, such as a vehicle accident. Perhaps because of this, the state has had to intervene to protect us from our own risky behaviors—think seatbelt laws and antismoking regulations.

But our failure to respect the earth’s power to obliterate us, by building homes in at-risk areas, seems to contradict Slovic’s conclusion. In some places, people seek out dangerous flood zones because they have more fertile soils to farm or a pleasant riverfront location; others risk dangerous avalanches because of the fun and challenge of climbing mountains; still others choose to live in San Francisco because it’s a pretty and dynamic city. The U.S. Geological Survey recently raised the likelihood of San Francisco experiencing the “Big One”—an earthquake of magnitude 8 or more—in the next 30 years. Quite something to consider if you’re taking out a mortgage there.

By continuing to build and live in known risk zones, we effectively turn a natural disaster into a manmade one. Human effects, such as climate change, deforestation, rerouting of rivers, or other land-use changes amplify the risks of natural events. But if anything, we appear to be more blinkered than we would expect to these manmade risks.

Most people have, owing to birth or circumstance, no choice about living in a risky place. They are the unfortunate victims of quakes (such as the one that hit Nepal in April), volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, deadly disease, and so on.

We can reduce these risks. Buildings in quake zones, such as San Francisco and Tokyo, have to comply with safety regulations—the equivalent of a seatbelt. But what about those in poor countries? When disaster strikes, the losses are more often economic for rich countries and mortal for poor ones.

And because many of our manmade risk amplifiers, such as climate change, now have global effects, surely it’s time we made our seatbelt regulations global too.