The Birth of Black Power

Stokely Carmichael and the speech that changed the course of the civil rights movement

It can hardly be called a park today. The site in the Mississippi Delta town of Greenwood where, in 1966, Stokely Carmichael electrified a crowd with shouts of “We want Black Power!” lies untended and unwelcoming. Its name—Broad Street Historical Park, announced on wooden boards between stone columns—speaks in two registers. Without question, the park bears historical importance, as noted by a marker commemorating the speech that changed the course of the civil rights movement. It is also lost to history, this forlorn block of overgrown grass in the storied Black neighborhood of Baptist Town, where the soulful music of blues legend Robert Johnson once stirred the air.

I had come to Greenwood to bear witness. In this picturesque town at the head of the Yazoo River, once a major cotton-shipping port, some of the long freedom movement’s most turbulent episodes had played out. In 1886, 50 or more white men set out on horseback from Greenwood to the courthouse in neighboring Carroll County, where they lynched at least 20 Black men for having the audacity to believe the justice system belonged to them, too. In 1955, just miles north of Greenwood, Emmett Till’s body was dredged up from the Tallahatchie River, three days after his murder, a cotton gin fan around his neck. The massive voter education and registration drives culminating in the Freedom Summer of 1964 were based here, launching Carmichael’s career as a community organizer.

As I followed a self-guided civil rights driving tour to the site of his speech one summer day, a half century after it was delivered, it took some time to realize that what looked like an abandoned lot was indeed the park. I began to circle the block toward a small open-air pavilion. Nearby, at the corner, stood the historical marker. Three young Black men were standing in the pavilion. I will admit to a certain anxiety, of feeling vulnerably white and female, as I parked the car and got out. One of the men wanted to ask me a question. “Why do people stop here to read that sign?” he asked. “What does it say? Because I can’t read.”

Was he playing me? I answered him straight. “I’m about to do the same thing,” I said. “It says there was—”

“—I’m just asking,” he interrupted. “I can’t read it.”

The second time sounded like insistence. It left me utterly confused. Who would tell a stranger that he was illiterate? I was not prepared, in the moment, to respond to such raw vulnerability, or even to fully acknowledge the assertion being made.

“Well, there was an important civil rights speech made here. You know there was a lot of civil rights activity, a lot of things that happened in Greenwood during the civil rights movement. You know that, don’t you?”

“Yes. I’ve heard about it. But that was before my time.”

“Right. You’re young. But there were important things, an important speech happened here. A lot of things happened here to create change, for the good.”

And that was all. I hurried to the marker, captured it for my Instagram feed, and left.

I quickly regretted my haste, my empty words, my reluctance to engage with the three young men idling on a summer morning in a lonely space that passed for a neighborhood park. I could have pointed to a nearby site where the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the force behind Freedom Summer, had made its headquarters. I could have shared something about Carmichael’s years of work in Greenwood and Leflore County as a SNCC volunteer, beginning as a Howard University student. I might have gained the answer to my question: whether he, whether they, really had been so badly shortchanged that they could not read. We might have had a real conversation.

But I sensed a gulf between us, stemming from what felt like my own fear. I had been careful to end my abbreviated speech on a positive note: “for the good.” I mean you no harm is what I meant for him to hear.

Carmichael had returned to Greenwood that night in June 1966 to help activist James Meredith send a message about fear in Mississippi. Two years had elapsed since passage of the Civil Rights Act, one year since the Voting Rights Act, and little had changed in the state. On June 5, Meredith had set out on foot from Memphis toward Jackson, with the goal of inspiring Blacks to register to vote and to transform their fears into positive action. When, on June 6, he was ambushed and wounded by shotgun fire, everything changed. Meredith’s single-minded “March Against Fear” became a rallying point for the movement. The leaders of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (Martin Luther King Jr.), SNCC (Carmichael), and the Congress of Racial Equality (Floyd McKissick) pledged to keep the march alive as Meredith recovered in a hospital.

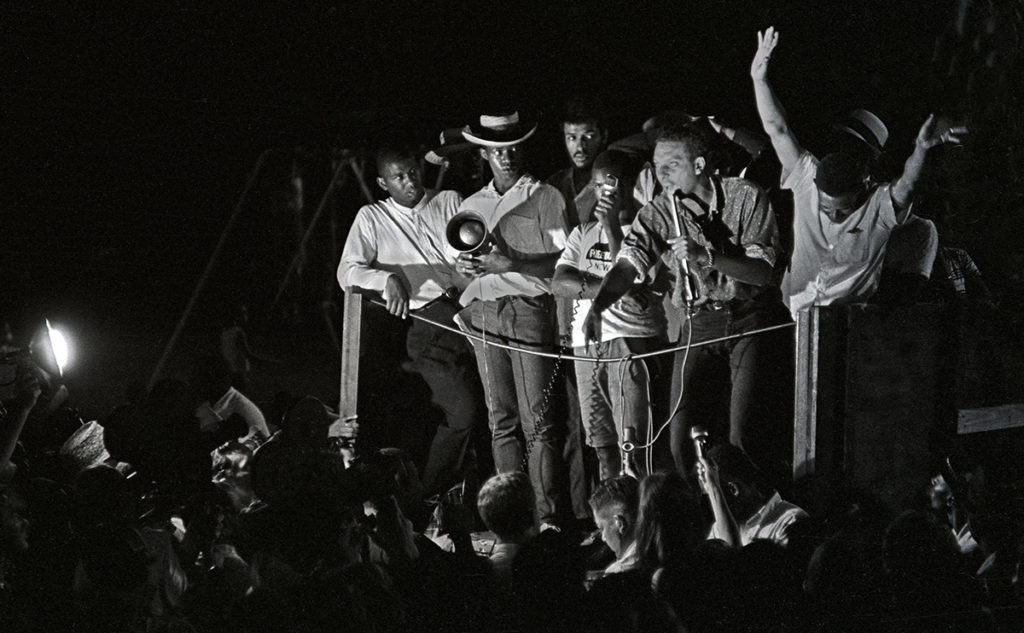

The marchers arrived in Greenwood on June 16. Carmichael’s fiery invocation of Black Power that night was born of frustrations, immediate and long-term. The immediate problem was that local white officials had denied the marchers permission to set up camp on the lawn of a Black elementary school—contradicting the word of local Black leaders. Arrested and jailed for trespassing, Carmichael posted bail just in time to make the rally that evening.

The longer-term, more fundamental concern for Carmichael was that the movement’s strategies of nonviolence seemed to have reached some kind of limit. During the previous summer, less than a week after President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles erupted. The conflict in Vietnam had divided the nation since the passage of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in 1964, which resulted in the dramatic escalation of a war that would claim proportionally more Black American lives than white.

A legislative battle was unfolding over equal access to housing—a prospect that threatened the integrity of white neighborhoods and challenged white wealth. This and other demands for reform in such areas as criminal justice and labor were structural, beyond easy concessions like access to lunch counters and even to voting booths. “White America was ready to demand that the Negro should be spared the lash of brutality and coarse degradation,” King wrote in what turned out to be his last book, Where Do We Go From Here (1967), “but it had never been truly committed to helping him out of poverty, exploitation or all forms of discrimination.” As this next phase of the civil rights revolution unfolded, nonviolent direct action seemed to belong to a vanishing era.

Far from a spontaneous outburst, Carmichael’s speech reflected a shift developing in SNCC’s strategic orientation, the merits of which were debated even while the marchers pushed forward. King’s reaction to the thunderous reception of Black Power that night in Greenwood was mixed. He conceded its “ready appeal” among “people who had been crushed so long by white power.” But he saw that the concept could widen an existing split in the ranks over whether to abandon the commitment to nonviolent direct action. Moreover, as he asserted during five hours of intense discussion the next day, the connotations of Black Power were all wrong. “I mentioned the implications of violence that the press had already attached to the phrase,” he recalled. “And I went on to say that some of the rash statements on the part of a few marchers only reinforced this impression.”

His worries were not misplaced. After Greenwood, mainstream journalists did sensationalize Black Power, aligning it with militant separatism. Whereas for Black audiences the term was a “righteous exhortation,” writes Carmichael’s biographer Peniel Joseph, for whites it carried a “violent foreboding,” possibly a forecast of “antiwhite violence and reverse racism.” Juxtaposed against television images of cities in flames, the term was certain to alarm even liberal whites.

And yet, the constructive elements of Black Power were understood within the circle of activists engaged in the march. Central concepts included self-determination and equitable access to the established levers of power, with the realistic ability to create social, political, and economic change. Whatever his level of discomfort with the phrase itself, King sympathized with Carmichael’s motivation in using it. Black Power, he writes,

is a response to the feeling that a real solution is hopelessly distant because of the inconsistencies, resistance, and faintheartedness of those in power. If Stokely Carmichael now says that nonviolence is irrelevant, it is because he, as a dedicated veteran of many battles, has seen with his own eyes the most brutal white violence against Negroes and white civil rights workers, and he has seen it go unpunished.

King locates the roots of Black Power in the elemental workings of slavery. The master’s physical power over the Black body was ultimately all—and everything—that slavery depended on, and this singularly white power lingered long after the legal fact of slavery was abolished.

Citing Kenneth Stampp’s landmark study The Peculiar Institution (1956), which laid to rest the myth that slavery’s foundations were benign, King quotes instruction manuals that circulated among enslavers. “Unconditional submission is the only footing upon which slavery should be placed,” wrote a white Virginian. In South Carolina, a slaveowner wrote that “the slave must know that his master is to govern absolutely and he is to obey implicitly, that he is never, for a moment, to exercise either his will or judgment in opposition to a positive order.”

This is what Black Power is responding to, King says. The call for Blacks to “cut themselves off from every level of dependence upon whites” is a “react[ion] against the slave pattern of ‘perfect dependence’ upon the masters.” Black Power, King concludes, “is a psychological reaction to the psychological indoctrination that led to the creation of the perfect slave.”

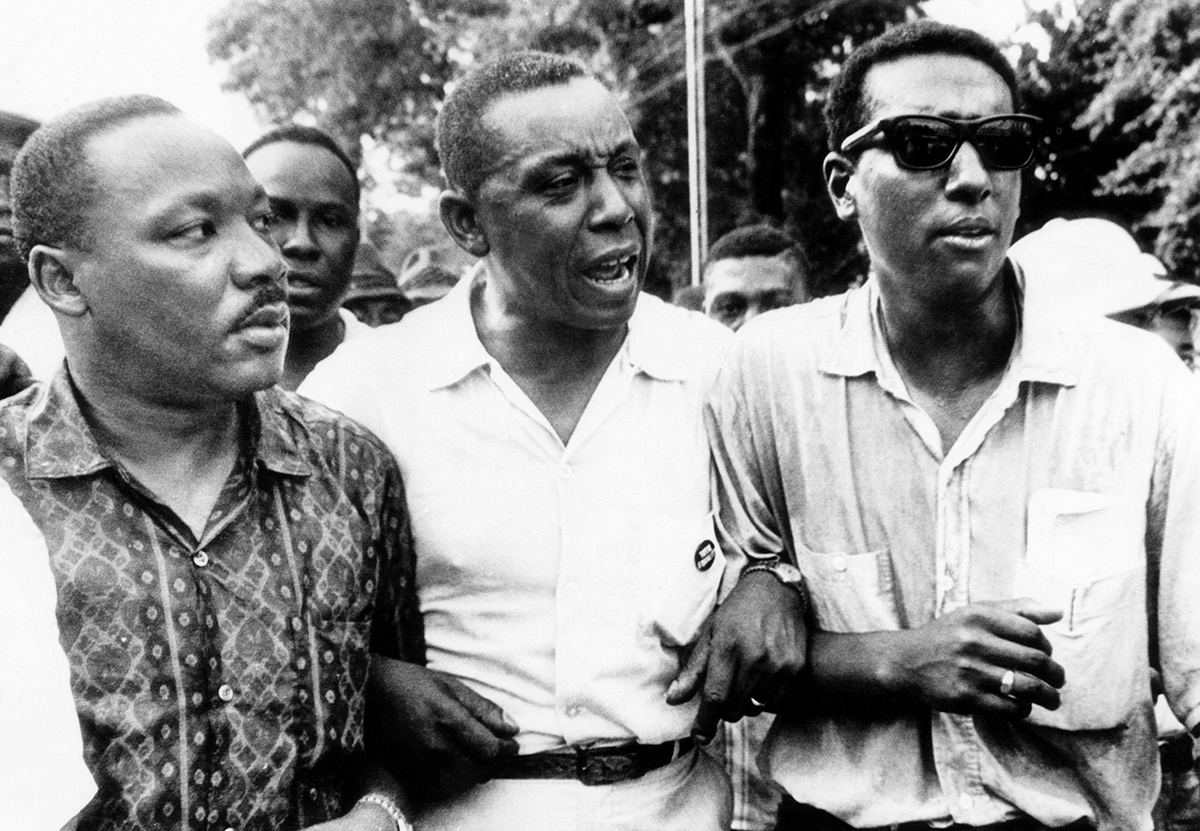

Carmichael (right) with King and activist Floyd McKissick, in Canton, Mississippi, in July 1966 (Everett Collection/Alamy)

Phrases like “perfect dependence” and “unconditional submission” are not chance wording. They come from a legal authority well known by the 1830s. State v. Mann, an 1829 opinion of the North Carolina Supreme Court, set a broad standard for an enslaver’s powers of correcting a disobedient slave. The decision overturned a white man’s assault conviction for shooting an enslaved woman who was running to escape being beaten by his hand. Writing for the court, Judge Thomas Ruffin, himself a slaveowner, proclaimed, “The power of the master must be absolute, to render the submission of the slave perfect.”

Analogies to the authority of parent over child, tutor over pupil, or skilled master over apprentice fail, because in each, the lesser status constitutes a step to a higher position in freedom. “With slavery it is far otherwise,” Ruffin wrote. “The end is the profit of the master, his security and the public safety; the subject, one doomed in his own person and his posterity, to live without knowledge, and without the capacity to make any thing his own.” In chilling yet unassailable logic, Ruffin proceeds to dissect the master-slave relationship. No one remains enslaved out of a sense of duty or devotion, he points out:

Such services can only be expected from one who has no will of his own; who surrenders his will in implicit obedience to that of another. Such obedience is the consequence only of uncontrolled authority over the body.

Because the basis of slavery is sheer physical power, this argument goes, the master must hold “absolute” powers of correction.

When King drew the connection between Black Power and the power of the enslaving master, he remained one step removed from State v. Mann. Phrases like “to govern absolutely” and “to obey implicitly” come from those planter tutorials, which in turn echo Ruffin’s opinion. State v. Mann itself lay largely unread in the 20th century until the 1970s, when, as the concerns raised by the civil rights movement found a forum on college campuses, scholars turned their attention to the law of slavery.

Focusing on the conundrum of the enslaved body as both person and property, some contemporary scholars have read State v. Mann as a statement on the civil law of property. In The Meaning of Property (2010), for example, Jedediah Purdy emphasizes the case’s contribution to an area of law that would evolve into the domain of free labor contracting. Karla Holloway, in Legal Fictions (2014), associates Ruffin’s articulation of the legal right to power over a slave with an ancient notion of sovereignty—patria potestas, or the power of the father—arguing that it parallels the master’s “legal claim as a property owner.” Similarly, federal judge James Wynn has argued that Ruffin’s description of the enslaved as an insentient being, “one who has no will of his own,” aligns with principles of property law, even though Ruffin understood that treating people as property was “ultimately a legal fiction.”

The property law analysis makes some sense. A “legal fiction” that drains the humanity from an enslaved woman fleeing for her life invokes a social construction that has held potency long since the legal end of slavery. It comes down to us in what King called the “thingification” of human beings. And yet State v. Mann was a criminal case. The charge was assault and battery. To situate it within the civil law of property is to obscure its full, and fully contemporary, force as a statement of a fundamental power relationship.

Earlier Black intellectuals understood State v. Mann to pose a problem of power immorally wielded. Booker T. Washington noted that in asserting that the end of slavery is “the profit of the master,” Ruffin’s opinion “brings out into plain view an idea that was always somewhere at the bottom of slavery—the idea, namely, that one man’s evil is another man’s good.” But the truth about slavery, he counters, is “just the opposite … namely, that evil breeds evil, just as disease breeds disease, and that a wrong committed upon one portion of a community will, in the long run, surely react upon the other portion of that community.”

W. E. B. Du Bois saw in the opinion the relationship between Black power and white fear. Alluding ironically to the case, he remarked that life in the South after the Civil War would have been hard enough even if all the freedmen had died. But given that four million slaves had survived into freedom, each one—here he quoted from State v. Mann—having been “ ‘doomed in his own person, and his posterity, to live without knowledge, and without the capacity to make any thing his own,’ ” each one was “bound, on sudden emancipation, to loom like a great dread on the horizon.”

Lawyer and civil rights activist Pauli Murray knew that while slavery existed, State v. Mann was even used to justify rape—with potentially far-reaching consequences. In Proud Shoes (1956), she looks back at her mixed-race North Carolina family to her great-grandmother Harriet, enslaved to James Smith, head of a prominent family connected to the University of North Carolina. Harriet, a beautiful young woman assigned as servant to Smith’s daughter Mary, was repeatedly raped by one of Smith’s sons, Sidney. Murray’s grandmother was the child of that violent union.

Mary was “mortified,” writes Murray.

She felt Sidney had disgraced them all. Not that she had ever seriously questioned slavery as a way of life or the foundation of her family’s wealth and privilege. Nor had she ever disputed a master’s absolute right over his slave’s person even when it included assault and rape. She had heard her father and Judge Thomas Ruffin expound these views too often to believe otherwise.

Harriet subsequently bore three more daughters by Mary’s other brother, Frank, and life in the Smith household became fraught with conflicting roles and emotions. “Miss Mary” was the aunt of the enslaved children of her slave. “Like Harriet, she was drawn deeper and deeper into a quagmire,” Murray writes. “She was to experience a common bondage with Harriet which transcended the opposite poles of their existence as mistress and slave.”

The perversions and inversions of power and fear constitute the most enduring legacies of slavery.

Ten days after my awkward conversation with that young Black man in Mississippi, a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, shot an unarmed Black teenager, abandoning his body like roadkill in the August sun. Following close upon the death of Eric Garner in the chokehold of a New York City policeman, the killing of Michael Brown jolted white Americans awake to the brutal realities of police power and the Black body. Among Black activists and their allies, Ferguson became the moment that galvanized the emerging Black Lives Matter movement, which had coalesced in 2013 in response to the vindication of the white neighborhood vigilante who had killed Trayvon Martin. Others quickly followed: Tamir Rice, Walter Scott, Freddie Gray, Sandra Bland …

More than six years have passed, the scenario repeating itself with gut-wrenching regularity: unarmed Black Americans slain by officers of the law, sworn or self-deputized. These incidents are painfully knitted into our common life, so much so that poet Elizabeth Alexander, writing in The New Yorker, calls young people born in the past 25 years the Trayvon Generation:

They always knew these stories. These stories formed their world view. These stories helped instruct young African-Americans about their embodiment and their vulnerability. The stories were primers in fear and futility. The stories were the ground soil of their rage. These stories instructed them that anti-black hatred and violence were never far.

During those six years, I tried 16, or maybe 60, times to finish this essay, only to face my numb inadequacy to the moment—a moment that calls those of us with white skin, and the associated unearned status, to circumspection. Black voices matter now, and it matters that we listen. At the same time, though, white Americans have a responsibility to reckon with hard truths about how the distorted power dynamics of the past shape the present. I can start by saying (some more of) their names: Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, Atatiana Jefferson, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor.

And George Floyd, whose prolonged execution at the knee of a white Minneapolis police officer, caught on video and seen around the world, drew agonizing cries of sorrow and new fear, firestorms of rage: the spark to the tinderbox. During a pandemic that itself has exposed unconscionable inequities in health and health care, masked actors have been unmasking the edifices of a criminal justice system that has never been neutral to Black Americans. Understanding the arresting power of symbolism, they are stepping up the pace of bringing down monuments to white supremacy, to a lost cause, statues built for the ages and shielded in masks of honor, duty, and tradition.

Just hours before Floyd’s murder, 1,200 miles away in New York’s Central Park, another confrontation had been captured on video. When Christian Cooper, a Black man quietly birdwatching, asked Amy Cooper, a white woman walking her dog, to comply with the leash law, she called the police. In a performance of hysteria tapping a deep cultural well of racialized fear, she accused the man calmly videoing her with threatening her life. (The irony in the accidental echo of the master-slave “family” name cannot be missed.) Amid the outrage over Floyd’s death, this story highlighted the everyday humiliations dealt to all Black people when white privilege is emotionally weaponized.

State v. Mann brought the master’s unbridled use of force within the sanctity of the law. Its warrant of immunity followed enslavers into the Deep South, where cotton production expanded and intensified to meet an insatiable world market. By 1850, under threat of the bloody lash, enslaved cotton pickers had increased their daily yield by 400 percent over pre-expansion levels. As historian Edward Baptist crisply puts it, “The shock of the whip made bales of cotton.”

Long after the abolition of slavery should have nullified State v. Mann, its relevance persisted, its essence simply adapting itself to new conditions. The Black codes enacted in the South immediately after the Civil War, for example, “were an astonishing affront to emancipation,” observed Du Bois in Black Reconstruction (1935), a “plain and indisputable attempt on the part of the Southern states to make Negroes slaves in everything but name.” Thomas Ruffin himself, by then retired from the North Carolina Supreme Court, kept his dependent laborers in a position much like slavery and in some ways worse: the terms of his sharecropper contracts, a Freedmen’s Bureau investigation found in 1868, so constrained “personal liberty” as to be “utterly foreign to free institutions.”

Accustomed to their mastery, Ruffin and others like him remained fond of the lash. The practice of whipping was so widely abused in North Carolina that, in December 1866, it was forbidden by military order. Ruffin was among the state delegation that personally implored President Andrew Johnson to rescind the order. Johnson had openly favored slavery, so the request was not implausible. But it was unsuccessful. Even under the relatively lenient terms of Presidential Reconstruction, the practice would not be tolerated.

President Johnson’s strategic ineffectiveness in reforming the South compelled a new Congress to enact stricter laws. The Reconstruction Act of 1867 imparted “a millennial sense of living at the dawn of a new era,” writes historian Eric Foner in Reconstruction (1988). Over the combined years of Presidential and Congressional Reconstruction, some 2,000 Black men served in all levels of government, reshaping the law to ensure the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of equality.

New statutes could not compel white men to share their power, though. Exploitation of Black labor continued apace. Even more abusive than the widespread practice of sharecropping was the convict-leasing system. Licensed by the fine print of the Thirteenth Amendment, former enslavers eagerly put prisoners to grueling work in the South’s emerging industrial landscape of railroads, mines, and factories of all sorts. Blacks were snared into this barbaric practice by laws that, despite repeal of the constitutionally offensive Black Codes, still were used against them on the slimmest of provocations. Black convicts were herded, shackled, forced to work under the eye of armed guards—cruelties “such as no tongue can tell nor pen picture,” reported an outraged Du Bois. “Hundreds of Southern fortunes have been amassed by this enslavement of criminals.”

The end is the profit of the master …

And something more than exploitation of Black labor came into play. The artificial increase of the numbers of Black criminals provoked an onslaught of mob violence. “White men became a law unto themselves,” Du Bois observed. “And the South reached the extraordinary distinction of being the only modern civilized country where human beings were publicly burned alive.” The Ku Klux Klan gained its footing after 1868.

… his security and the public safety.

But midnight raids were not the business of the gentlemen of the upper class. Judge Ruffin, for example, urged his son to stay clear of the Klan. He merely opposed its tactics, however, not its goals. “The whole proceeding is against Law and the Civil power of Government,” Ruffin counseled. Such dangerous vigilantism was no more than “an attempt to do good by wrong means.” His opinion remained private, though. As Foner points out, no one in authority would publicly decry what was tacitly understood. The comfortable elite were content to let others do their dirty work.

Although Ruffin would not live to see them through, the years of Congressional Reconstruction (1867–1877) were far more deadly and traumatizing to Blacks even than the era that followed. Du Bois interpreted events through the framework of power and profit versus shame and scarcity and fear:

Back of the writhing, yelling, cruel-eyed demons who break, destroy, maim and lynch and burn at the stake, is a knot, large or small, of normal human beings, and these human beings at heart are desperately afraid of something. Of what? Of many things, but usually of losing their jobs, being declassed, degraded, or actually disgraced; of losing their hopes, their savings, their plans for their children; of the actual pangs of hunger, of dirt, of crime. And of all this, most ubiquitous in modern industrial society is that fear of unemployment.

In short, as he saw it, the terrorist campaigns were the work of white men who were themselves afraid of losing their livelihoods to the newly free.

As Reconstruction came to its unceremonious end, white Southerners celebrated the release from federal oversight by proclaiming a new era of “Redemption,” a curious term conflating religion and the market. (Apt or not, it foreshadows King’s famous metaphor of the bad debt: “It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned.”) Though it would take more than a decade, and yet more violent oppression, by the turn of the 20th century, the white supremacist leaders of a defeated regime had regained firm control of state governments.

From that point, their unreconstructed policies would have to be carried out in a manner worthy of Ruffin’s proclaimed fidelity to the law: the law, that is, as redrawn to implement new federal guarantees of equal protection and voting rights for Blacks. As it happened, their reactionary agenda was abetted by a southward-facing Supreme Court, whose 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson constituted a mastery of form over substance. What followed was the familiar Jim Crow regime of discrimination through legal subterfuge: literacy tests and poll taxes to suppress the Black vote, separate but grossly unequal institutions, every possible tool of subordination within the letter of the law.

All the while, white terrorism raged on. The Equal Justice Initiative reports 4,075 lynchings in the South between 1877 and 1950. Gruesome scenes were captured on postcards, circulating among whites like memories of summer camp, tokens of warning to Blacks who would transgress the color line. Throughout the first half of the 20th century, extralegal measures buttressed the work of law enforcement to keep Blacks in fearful, if not perfect, submission, perpetuating the power of the master long after his authority should have been surrendered. Pauli Murray movingly evokes the long shadow of the past in her epic poem “Dark Testament,” written in 1943:

The drivers are dead now

But the drivers have sons.

The slaves are dead too

But the slaves have sons,

And when sons of drivers meet sons of slaves,

The hate, the old hate, keeps grinding on.

Traders still trade in double-talk

Though they’ve swapped the selling-block

For ghetto and gun!

Black men for decades had been suffering the consequences of a particularly virulent stereotype: the manufactured image of the Black man as bestial creature with primitive instincts, whose most fervent aim was to rape white women. The presumption of Black men’s sexually aggressive nature had arisen suddenly among southern whites after Reconstruction, for reasons Frederick Douglass and Ida B. Wells could clearly see.

A few months before his death in 1895, Douglass called out the dubious discovery of a new class of rapacious Black men as nothing but the latest campaign to keep them in their place, ultimately to deny them the power of the vote. Under slavery, he noted, Black men were not known to ravish their mistresses, not even while their masters were away fighting the war. During Reconstruction, white men did not charge Black men with rape to justify their violent response to so-called Negro rule. But Reconstruction was over. The white oligarchy had resumed its power. As Douglass wrote, “honest men no longer believe that there is any ground to apprehend Negro supremacy.” To cement the new political reality, he maintained, the myth of the omnipresent Black rapist could not have been better calculated. “It clouds the character of the Negro with a crime the most shocking that men can commit, and is fitted to drive from the criminal all pity and all fair play and all mercy. It is a crime that places him outside of the pale of the law.”

In her long campaign against lynching, Wells investigated case after case only to expose the frequent claim of rape as “the old thread-bare lie,” a cynical move in the relentless power game, a shameless excuse for mob murder. Lynching’s more likely causes were bad enough, as she documented, ranging from gambling to quarreling with a white man to practicing voodooism. But the pervasive lie projected a hypersexualized Black man, a grotesque image that preyed on white fears of “race mixing.” Morally debased and emotionally manipulative rhetoric instilled the widespread belief that white men should stand in vigilant defense of the sexual purity, if not the lives, of their women, while Black men, with reason, spent their days and nights in mortal fear of making any wrong move.

Those postcard images of lynchings—“of charred and blackened fruit / Aborted harvest dropped from blazing bough” (Murray, “Dark Testament”)—remain in circulation. So embedded in our psyches are they that we who never witnessed such a horror recognize the scene even with noose and hanging body edited out. (Lest you doubt it, look for the photo in poet Claudia Rankine’s brilliant Citizen.) Without the fabricated memory of the criminally aggressive Black man, the Scottsboro Boys might not have been sentenced to death on false charges of rape, or faced such a charge. Without it, Carolyn Bryant’s false accusation of Emmett Till might not have been believed, or made. Without it, George H. W. Bush’s Willie Horton scare ads in the 1988 presidential campaign could not have succeeded. Without it, Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson might have seen Michael Brown as a human being to be reasoned with, not a “demon” that invited attack. Without it, Amy Cooper might not have called the police on a Black man armed only with a cell phone.

Without it, I might not have hesitated to speak to a young Black man who only wanted my help to read a sign.

My white female body is implicated in a binary struggle older than the nation. An implicit racial hierarchy defined and delimited the terms of my East Texas childhood, during which the only Blacks with access to white neighborhoods were gardeners and domestics. Hundreds of years of elaborately coded white supremacy, meant to ease my place in the world, paradoxically impoverished my early understanding of it.

It’s quite possible that the young man I encountered at Broad Street Historical Park was illiterate. At the time of my visit, in 2014, the Leflore County school district had been taken over by the State of Mississippi for poor performance and mismanagement, and state takeover of the Greenwood district was being discussed. Decades of white flight (that fear again) had resulted in heartbreaking outcomes for those left behind. I learned about these developments only later, in the course of trying to come to terms with what he had said to me—and with my reaction.

As an early SNCC organizer in Greenwood, Carmichael had responded with sympathy to the condition of poor and uneducated Black sharecroppers. He saw that their circumstances were little changed from those of their ancestors under slavery. Like Malcolm X, Du Bois, and Douglass before him—like Thomas Ruffin in his own way—he understood that their suffering was perpetuated by structures of wealthy people’s economic self-interest. He also understood, like each of those men, that those structures were only as sturdy as the allegiance of Black labor, whether commanded under slavery or coerced in freedom.

As Carmichael would write, with fellow activist Charles V. Hamilton, in Black Power : The Politics of Liberation (1967), the generational effect of callous exploitation had been to breed “a race of beggars. We are faced with a situation where powerless conscience meets conscienceless power, threatening the very foundations of our Nation.” His response projected a radically inclusive vision of American democracy, one that, in the words of Joseph, his biographer, “stretched beyond the imagination of the Constitution’s framers.” It was a bold proposition that, as Carmichael put it, involved “putting power in the hands of the poor and letting them make their own plans.” It meant taking a fresh look at institutions, evaluating and restructuring them according to their capacity to address problems equitably. It meant questioning where and how to invest resources and reallocating them to gain more just outcomes.

For that brief moment, when Carmichael proclaimed Black Power in Greenwood, he and SNCC and King were aligned. To SNCC, the key to progress lay in registering Blacks and motivating them to vote their interests. (They “had Black Power in mind long before the phrase was used,” Carmichael wrote.) And though King disagreed with Carmichael’s refusal to rule out violence as a possible tactic and he chafed at the term “Black Power,” he agreed that extending political power to those who had been denied it was essential, and that self-respect, not fear, should be the movement’s driving force. Speaking to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1967, continuing to explore the question of “Where do we go from here?” he contended that “the movement must address itself to the question of restructuring the whole of American society.”

But the revolution in democracy did not come. The Black Power movement, brought to life as the Black Panther Party among sharecroppers in Lowndes County, Alabama, was soon overtaken, first in the popular imagination and then, in fact, by an aggressive new militance centered on the West Coast. Carmichael and SNCC parted ways. His belief that Blacks must first build power structures apart from whites ultimately led him to Pan-Africanism and to Africa. King was assassinated. Cities burned. The conflict in Vietnam tore lives and families and finally the country apart—all this before the young men in Broad Street Historical Park were born.

What might I have said to the one who spoke to me, this inquisitive member of the Trayvon Generation who had grown up surrounded by poverty yet in the shadow of giants? In vastly unequal measure, each of our lives had been buffeted and bruised by the oscillating forces of racialized power and fear. Perhaps we could have started by studying that marker. We might have appreciated the courage it took for Carmichael, King, and the rest to march against fear at a time when the white man’s claim of absolute power—sanctioned so long ago in State v. Mann—could still result in deadly retaliation. Perhaps we could have had the beginnings of a conversation about Blackness, whiteness, and why, after 50 years, so much seemed the same. The seeds of change, after all, had been planted in Greenwood, right there under our feet.