The Bonanza King

An excerpt from Gregory Crouch’s biography of John William Mackay, the 19th-century silver mine magnate

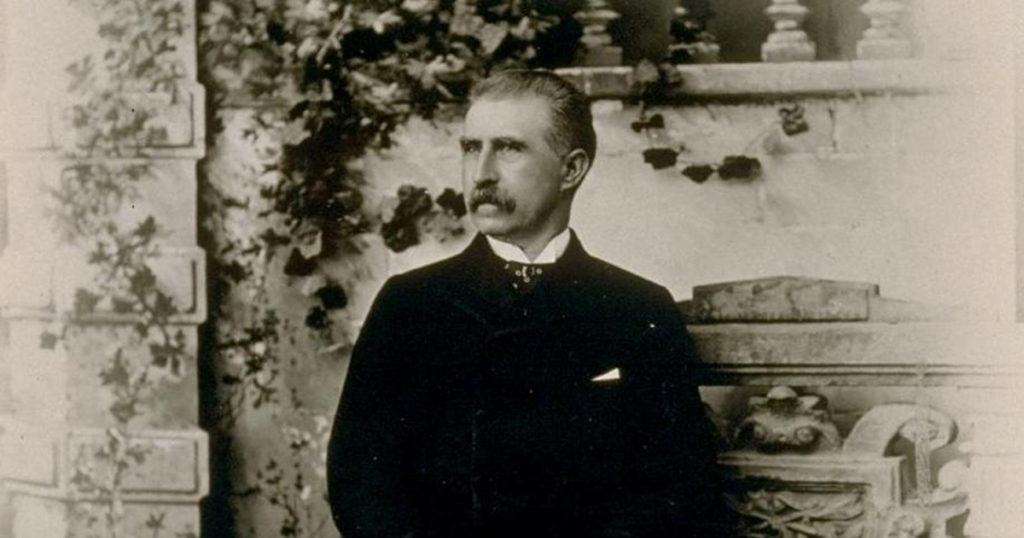

We’re all familiar with the rags-to-riches tale that lies at the heart of the American dream—the immigrant who stumbles upon a golden opportunity, propelling him to untethered heights of prosperity and fortune. As Gregory Crouch writes in The Bonanza King, there is no greater epitome of this dream than John William Mackay, an Irish-American prospector who struck silver and became one of the wealthiest men of the Gilded Age. In this excerpt from Crouch’s book, the class divisions between old and new money play out in Imperial Russia at the 1883 coronation of Czar Alexander III, where a self-made man mingles with emperors and becomes the talk of the town.

President Chester Arthur had asked Mackay to serve as special ambassador of the United States at the coronation of Czar Alexander III, whose father had been assassinated by bomb-throwing Nihilists two years before. Fear of the Nihilists motivated the long delay, but whisperings that “the present Emperor was only half a Czar so long as he remained uncrowned” eventually became too loud to ignore.

Telegrams to California described “the whole European press” fawning over the magnificence of Mackay’s private train carriage and the fifteen sumptuous dresses carefully hung in his wife’s private baggage car. Muscovites evinced much interest in “the Big Bonanza” and his wonderful silver mines in the tumult of events leading up to the grand coronation, considering him “one of the most interesting personages attending.” At the czar’s reception for the diplomatic missions held a night or two before his official investment, John Mackay chatted pleasantly with the Russian empress, fielding her questions about California.

The breathtaking coronation spectacle took place inside the Kremlin’s Cathedral of Michael the Archangel. The ceremony of chanting, bowing, receiving, anointing, addressing, faith-professing, cross-kissing, enrobing, and praying culminated when an attendant brought forth the imperial crown on a velvet cushion. The czar picked up the crown, held it high so all could behold its bejeweled magnificence, and put it on his own head. The New York Times’ man in Moscow found the ceremony “fully worthy of the occasion of the assumption of autocratic power by the absolute ruler of eighty millions of people.” A veteran diplomat considered the pageant the most spectacular and imposing he’d witnessed during a thirty-five-year career. Outside, in the city, mounted Cossacks patrolled every street, their steely eyes peeled for the Nihilists. At the ball held afterward, the new czar decided that Mrs. Mackay was the best-dressed woman present. Not even the stupendous pomp and barbaric splendor of a Russian imperial coronation could dim Louise Mackay’s star.

John Mackay never recorded his thoughts on the occasion, but of all the splendid personages present, he’d possibly had the lowest birth—which wouldn’t have caused him the least bit of shame. He must have been quietly proud of his wife, too, watching her enjoy the ball, fully aware that she’d covered every bit as much improbable distance as he had himself. They circulated with “the finest people in Europe.” Unfortunately, John Mackay found most of them unimpressive. Mackay was chivalrous to a fault, and nobody ever heard him utter an unkind word about any woman, of any station, either in public or in private. He displayed rather a lot less charity toward male members of the European nobility. Of them, in private, he was “profanely contemptuous.” He called them “bums and parasites” who “ought to go to work as I did.” In high company, Mackay took malicious pleasure in telling European aristocrats that he’d once been a common miner. Yes, he’d cooked his own food, and yes, he’d washed his own clothes. “It was either that or go dirty,” Mackay said. He’d been born in Ireland, he’d relate, the poorest country in the world, scion of a long line of Irish “bogtrotters.” He’d gone barefoot as a child and shared a dirt floor with the family pig. Louise feigned “mortification” and embarrassment in company, but she’d known the rude press of poverty herself. They’d traveled the hard roads their European associates had not. John and Louise Mackay had come as far as—and perhaps farther than—anyone else in the world, from the slums of New York and the filthy, transient mining camps of California to serve as their country’s official ambassadors at a Romanov coronation.

From The Bonanza King by Gregory Crouch. Copyright © 2018 by Gregory Crouch. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.