The Bully in the Ballad

Was Mississippi John Hurt really the first person to sing the tragic tale of Louis Collins?

Josh Ritter’s “Folk Bloodbath” is a haunting, hallucinatory song featuring the title characters from three great American murder ballads: Stacker Lee, Delia Green, and Louis Collins. Ritter methodically kills them all off and inters them in the same graveyard: “And out of Delia’s bed came briars, / And out of Louis’s bed a rose, / And out of Stacker Lee’s came Stacker Lee’s cold lonely little ghost.” It’s a strange and lovely mashup, a sidelong commentary on the curious human tendency to set brutal stories to beautiful melodies, and to tell those stories over and over again, in endless variations. Which makes it a little surprising that Ritter chose to build the song around “Louis Collins” and its famous refrain, “The angels laid him away.” It’s the least typical murder ballad in his trinity—more of a threnody, and one with minimal narrative. And whereas Stacker Lee and Delia Green have appeared in American ballads for more than a century, rambling through countless and ever-evolving variants, “Louis Collins” is something different—less the property of “the folk” than of one particular musician: Mississippi John Hurt, whose 1928 recording has always been definitive.

Little can be learned about how most classic murder ballads were composed, though their lyrics tend to draw from actual events. Stacker Lee really did shoot Billy Lyons, and Delia went to rest, and Duncan shot a hole in Brady’s breast, and John Hardy shot a man on the West Virginia line. We know all of this because researchers have tracked down the articles, inquests, and death certificates related to the figures in question. Here, then, is another way in which “Louis Collins” has been an outlier: everyone assumed that Mississippi John Hurt wrote the song, but no one knew anything about the killing that inspired it.

In the song’s brief narrative, Louis Collins is murdered by two men, Bob and Louis. Neither of those names sounds contrived, and the killing of Louis by a man named Louis sounds authentic almost to a fault. The potential confusion forces Hurt to refer to the victim, awkwardly, by his last name: “Oh, Bob shot once, and Louis shot too / Shot poor Collins, shot him through and through / The angels laid him away.” Surely, if you were a songwriter taking liberties with a story you’d heard, the first thing you’d change would be the name of that other Louis.

According to a 2011 biography of the singer, Mississippi John Hurt was indeed memorializing an actual death. “[Collins] was a great man, I know that,” Hurt said, “and he was killed by two men named Bob and Louis. I got enough of the story to write the song.” He also suggested that the murder might have taken place in Memphis. In late 2015, Patrick Blackman of Sing Out! magazine wrote that “John Garst, the chemist turned amateur folklorist who uncovered the story behind the murder ballad ‘Delia’s Gone,’ ” had identified two possible but not likely namesakes for “Louis Collins”—a man who was killed in an 1880 barroom fight in Texas and a prominent West Virginian named Lewis Collins who was murdered in his own bed in 1924. “Though radio was in its infancy as a tool of mass media,” Blackman wrote, “that murder might have been the subject of gossip over 500 miles away in Mississippi when Hurt was a young adult—but the details are wrong in comparison to the lyrics.”

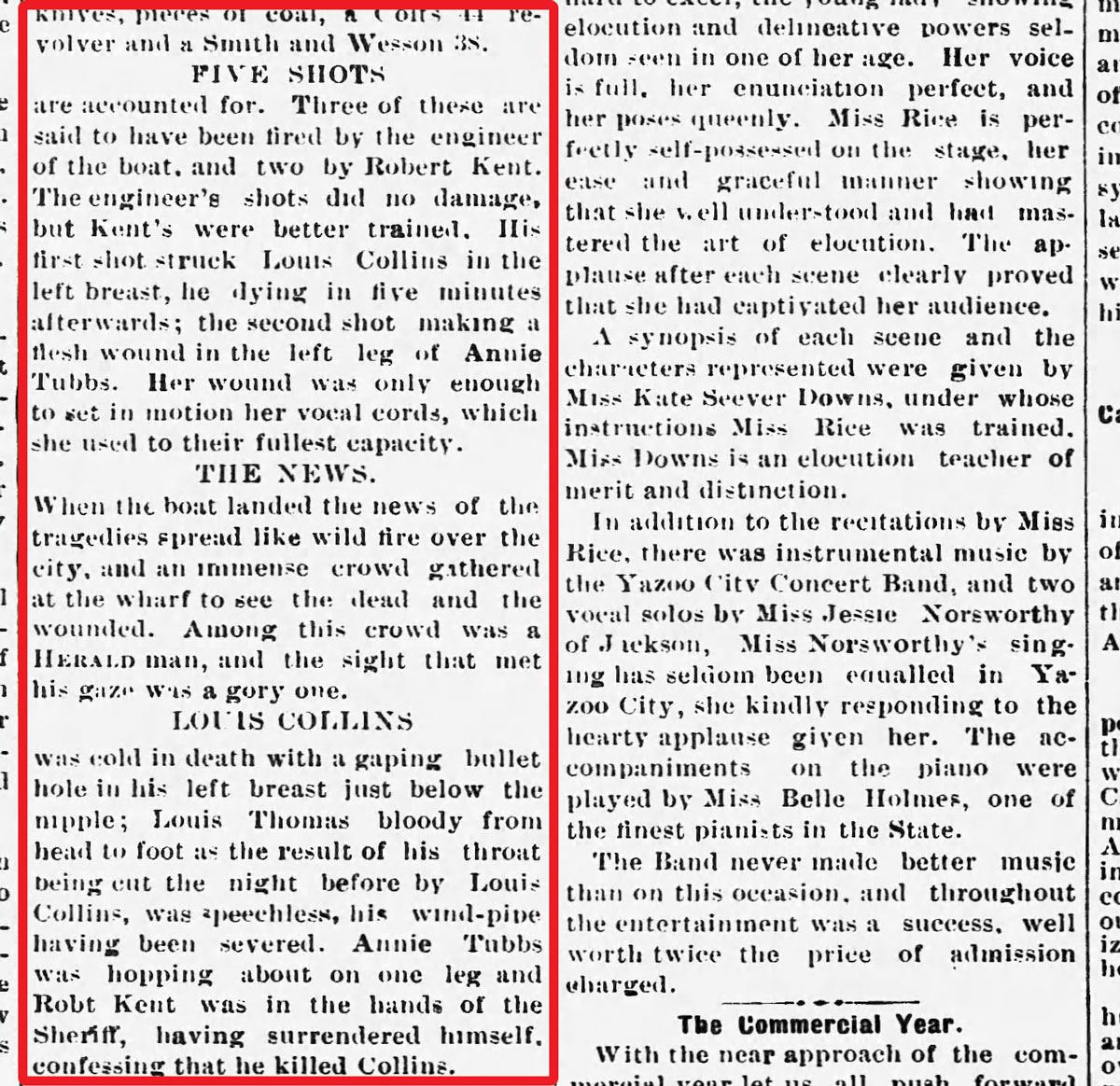

One day in the summer of 2019, I decided to dig deeper into the story. The recent digitization of old newspapers has been a bonanza for folklorists and music historians, and “Louis Collins” suddenly struck me as eminently researchable. I logged in to newspapers.com and entered the search terms “Louis Collins,” “Robert,” and “shot,” limiting my results to papers from Mississippi and the four adjacent states. In a matter of minutes, I had cracked the case, though I noticed that someone had beaten me to it. The article was bordered by a thin blue “clipping” outline—the digital scissor work of another researcher, “chris340.” At any rate, there it was: a drunken melee on a Mississippi riverboat excursion from Vicksburg to Yazoo City, in August 1897. It allegedly began with a knife fight between Louis Collins and Louis Thomas and ended when Bob Kent shot Collins to death. According to the Yazoo City Herald, “When the boat landed the news of the tragedies spread like wild fire over the city, and an immense crowd gathered at the wharf to see the dead and the wounded.” Yazoo City is about 65 miles from Avalon, where Hurt grew up. He would have been about four years old when the story started circulating. That the killing took place on a riverboat, I reasoned, could account for his having placed it in Memphis.

The article was full of hearsay and conflicting narratives, as was every scrap of subsequent coverage I could find. What seemed beyond dispute, though, was that this was the killing that had inspired Hurt’s song. I had my answer. Here also was yet another example of the novel power of keyword-searchable archives—needles in haystacks are easy enough to find, it turns out, when you’ve got an industrial-strength magnet.

I thought my research into Collins had come to an end. But this past summer, the music historian and folk blues guitarist Elijah Wald sent me a sound file he’d requested from the Library of Congress—a fragment of the song “Bully of the Town.” Recorded by John Lomax in 1933, it was an a cappella performance by an unidentified inmate at the Tennessee State Penitentiary. I’d been researching the Stacker Lee legend, and Wald was working on a book about the early blues. The “bully song” genre was relevant to both of our projects. (Bully songs are exactly what they sound like. Their lyrics depict a bully who terrorizes a town and/or gets his comeuppance; they were wildly popular in the 1890s—particularly with white audiences that liked to laugh at musical portrayals of violent Black men.) Wald noted in his email to me that the fragment he’d requested was in fact “a variant of the Louis Collins ballad that Mississippi John Hurt recorded, with just a passing mention of the bully.”

It’s only 39 seconds long. In a strong tenor, the inmate sings, “Louis Collins was a bully of the town, / Till little Kent, he laid him down, / And the angels laid him away.” He repeats that verse, then closes with, “All the women went dressed in red, / When they heard that bully was dead, / And the angels laid him away.” The fragment has the same verse structure and refrain as Hurt’s “Louis Collins” and very nearly the same melody. But the character of the song is completely inverted: Louis Collins is now a bully who has gotten his, and whose death is cause for celebration. What really had me leaning into my laptop, though, was the name of the avenger. Little Kent. Bob Kent.

When I mentioned what I’d learned from the Yazoo City Herald—that Louis Collins’s killer had been a man named Bob Kent—Wald pointed out the implication. Since “this singer doesn’t call him Bob and Hurt doesn’t call him Kent,” he wrote, “and the killing happened more than 30 years before either of them recorded it, I assume they both are singing variants of an earlier version that had the full name.” Hurt, in other words, was not the original author. “Louis Collins” had just been reclaimed for that most celebrated of folk-song composers: Anonymous.

Why, I wondered, had Hurt said he’d written it? He wasn’t known as a prideful or proprietary musician; in fact, he was notably self-effacing for a genius. Original compositions were only a small part of his repertoire, and he cheerfully acknowledged his debts: “This is one of Lead Belly’s songs I learned off the record,” he announced in one of his last studio sessions, introducing “Goodnight Irene.” Then again, authorship is a pretty fraught concept where old music is concerned. Did Lead Belly actually write “Goodnight Irene”? Depends on whom you ask, and what you mean by write.

I also wondered which “Louis Collins” likely came first: the mourned man, the cruel man, or some other man altogether. The refrain, “The angels laid him away,” suggests a charitable view of the victim. And yet, both versions have people reacting to the news of Collins’s death by dressing in red—not your typical funerary color. The “red” / “dead” couplet is actually an ambiguous “floating verse” that appears in numerous folk songs. People “re-rag in red” upon the deaths of the villain Brady, the hero Casey Jones, and everyone in between. In “Folk Bloodbath,” Josh Ritter even tips his Stetson to the tradition by having “all of them gentlemen” turn out in red for Delia’s funeral.

Learning what the real Louis Collins was like might provide some hints as to how he was first depicted in song, but that’s hard to do when his name appears only in some muddled hearsay about a riverboat brawl. The Jackson Clarion-Ledger reported that “Collins [had] been jailed several times for different offences,” but he was a Black man living in 1890s Mississippi, so that doesn’t tell us much. The strongest argument that the bully song came before the lament, I decided, was that the bully song genre was peaking in popularity at the time of the killing.

A few days after our email exchange, Wald announced the discovery on his blog and shared the link on Facebook, where his friends list is full of authorities on American music. One of them is David Evans, a professor emeritus of musicology at the University of Memphis. He commented that the Louis Collins killing had been discussed at length by columnist Chris Smith in Blues & Rhythm—an English magazine beloved by blues completists. Smith generously sent me what he’d written, a total of five pages spanning three issues of the magazine from late 2017. (He also confirmed that his newspapers.com screen name is “chris340.”) Smith, I now learned, had dragged a fine-mesh net through the digital archives for traces of Louis Collins, Bob Kent, Louis Thomas, the riverboat’s engineer, and several bystanders. Like me, he was struggling to reconcile the murderously violent man described in the articles with the “great man” Hurt believed he was elegizing.

The pages Smith sent included a response to his columns by the aforementioned David Evans. “I think the most likely scenario,” Evans wrote,

is that Hurt reshaped, recomposed, added material, or something such as that, to an already existing obscure and more or less localized traditional ballad. The song is what my old professor D. K. Wilgus called a “blues ballad.” Many, if not most, of these songs had a three-line structure of rhymed couplet and one-line refrain, a structure which became adapted to the familiar twelve-bar three-line blues. … [V]irtually all blues ballads using this … form were composed about events between 1890 and 1910, and it is a pretty safe assumption that the ballads were composed shortly after the events. … Of course, the older songs continued to be sung in later decades, some of them up to the present day. But black ballad composition was largely over by the 1920s.

It was a master class. Five years before Wald’s discovery of the 1933 variant, Evans had performed a lyrical carbon dating on “Louis Collins,” effectively ruling out Mississippi John Hurt as the song’s originator. And Evans wasn’t done. Hurt’s focus on the victim and the grieving survivors, rather than on the killer, was unusual for a blues ballad about a “bad man.” But it was typical of

the older Anglo-American ballad and sentimental song tradition. That’s not so surprising in Hurt’s case, as he often performed for white folks and had a lot of songs that would have appealed to white tastes. … This sentimental and victim-focused quality might be what Hurt added to whatever version of the song he heard and [what] allowed him to claim that he composed the song.

Such claims of having “made up” a song are, of course, very common in blues among artists who adapt traditional material or even do blatant “covers” of another artist’s recorded song.

It struck me as one of those extraordinary cases in which deep learning begins to resemble clairvoyance. Not only had Evans posited the existence of other, older versions of “Louis Collins,” he had also all but predicted that when one was discovered, it would be a song about a bad man.

If we trust Evans’s inferences—and Lord knows, I’m inclined to—we now have pretty persuasive answers to both of the big questions that the 1933 recording raises. Louis Collins was a bully of the town, at least when he first entered the folk song tradition. And by radically recasting a bully song as a mournful ballad—an achingly beautiful lament, at that—Mississippi John Hurt made a case for himself as its author.