The Uninnocent: Notes on Violence and Mercy by Katharine Blake; FSG Originals, 224 pp., $17

In The Uninnocent, Katharine Blake, an adjunct professor at Vermont Law School’s Center for Justice Reform, confronts a horrific murder committed by her cousin Scott, who as a teenager received a sentence of life without the possibility of parole. In detailing the facts, the aftermath, and her attempts to connect with Scott, Blake ruminates on the nature of heartbreak, forgiveness, family, justice, mercy, and redemption.

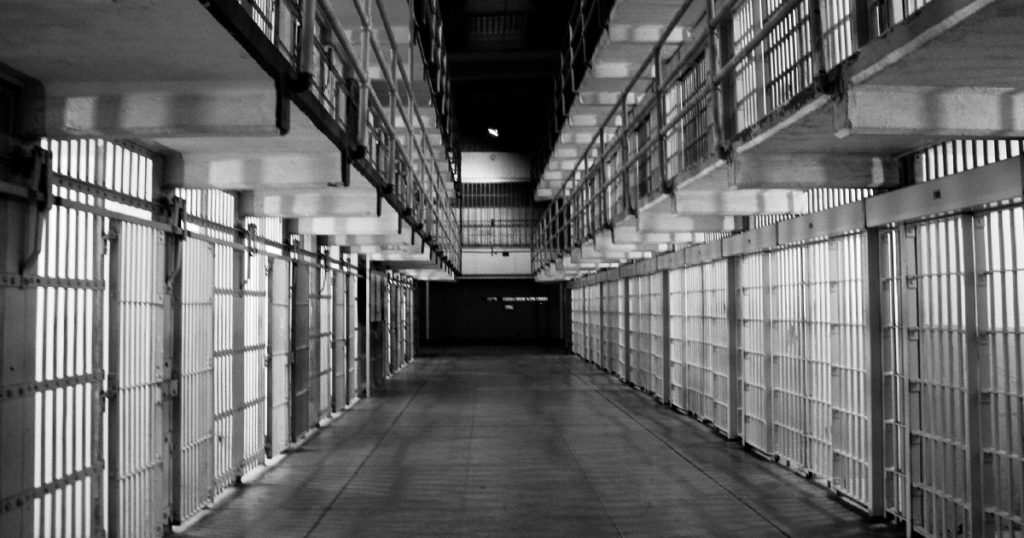

The Uninnocent is a hard book. It is not hard to read: the slim volume is filled with Blake’s lilting, at times poetic sentences—the cellblocks in San Quentin Prison are “like library stacks, rows and rows of stories down every dimly lit hall.” Her spare and often gorgeous prose is enriched by frequent quotations from Sumerian proverbs, Saint Augustine, the King James Bible, C. S. Lewis, and James Baldwin, among many others.

Blake’s book is hard to read because of what it asks of us: to have mercy for Scott. Given what Scott has done, this imploration will strain to the breaking point most readers’ capacity for grace and forgiveness. I confess that in the end I was unable to offer Scott either one. While that stinginess no doubt speaks to my limitations as a human being, it also indicates the book’s limitations as a persuasive document.

If uninnocent means blameworthy, then Scott is the word’s embodiment. When he was 16, he left his home, box cutter in hand, and headed to a trail nearby. There he waited until Ryan, a nine-year-old boy, rode by on his bicycle. Just behind Ryan were his mother and twin brother, but in that one shimmering moment, Ryan was alone and terrifyingly vulnerable. Scott grabbed the little boy, stabbed him in his back and chest, and then slit his throat. When Ryan’s mother, a physician, came upon her son seconds later, she found him lying on the ground, his head nearly severed from his body.

Blake describes Scott’s attack as a “fight,” implying a struggle between two people in which both of them have a chance, however slight, of emerging the victor. But Ryan never had a fighting chance, or any chance at all. There is no mutuality, no excuse, and no reason, so we look to Blake to help us fathom why.

It is here that her book falls short. Never close with her cousin, Blake had not seen him since they were children. She sends him books, but for a time cannot bring herself to answer his letters. When she finally does visit Scott in prison, years later, we don’t know what they say to each other because she doesn’t tell us. Asked at a dinner party why she cares about her cousin, Blake falters but later wishes she had said, “It’s hard not to care about someone when you begin to know him.” But what Blake knows about Scott she keeps to herself, leaving the reader pressed up against the glass, trying to see into a dark room.

A law student when the crime occurred, Blake provides a clear description of how the case unfolds: confession, arrest, charges in adult court, a guilty plea, and a subsequent death-in-prison sentence. These procedural steps, however, yield little insight into Scott himself. Blake draws an equivalency between Scott and Ryan: “both boys had fallen prey—one to the violence of murder, and the other to a slow and steady violence, the invisible invasion of disease, ravaging for days and months, maybe years.” But she offers no evidence to back up her claims—either that the boys’ suffering is in any way comparable, or more fundamentally, what the source of Scott’s suffering is. Any possible reasons for his violence remain shrouded in mystery: though Scott is evaluated prior to entering his guilty plea, no diagnosis is forthcoming. Years later, Blake visits a Harvard psychotherapist to get his opinion about the theory that Scott might have suffered a psychotic break. How is that term defined? she asks. The psychotherapist explains that “it’s a defense against fear or intense pressure.” He asks Blake to tell him what Scott might have feared or felt he had to defend against. “I don’t really know,” she answers. “I didn’t know him very well.”

Her answer is unsatisfying in light of the monumental nature of Blake’s ask—that the reader interpret “heartbreak” to encompass what has happened to Scott and extend mercy toward him even though she does not dispute the appellate court’s conclusion that “there is no mitigation.” As Blake explains it, “What they meant is that there was no abuse or poverty, there was no disadvantage or neglect, there was not even a legal diagnosis. This was an upper-middle-class white teenager who walked out one day and killed a child.”

Mercy, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, means “compassion or forgiveness shown toward someone whom it is within one’s power to punish or harm.” Blake quotes the renowned defense attorney Bryan Stevenson, who has written that “mercy belongs to the undeserving.” He argues that mercy may even have the power to “break the cycle of victimization and victimhood, retribution and suffering … to heal the psychic harm and injuries that lead to aggression and violence, abuse of power, mass incarceration.” Stevenson is a scholar and practitioner of mercy. His genius lies in explaining to judges—including majorities on the U.S. Supreme Court—and the millions of people who bought his book Just Mercy (2014) or saw its film adaptation that his guiltiest clients are still human beings. In Stevenson’s rendering, they are three-dimensional and deserving of a second chance.

In Scott, we are faced with the ultimate test of Stevenson’s thesis. Drinking in Blake’s lovely sentences, the reader turns the pages and waits for the three-dimensional man to emerge, and with him the evidence that he has reckoned enough, repented enough, and received sufficient treatment so that he will never brutally attack another human being or take another life. We wait for the illumination that will allow us to see how Ryan’s parents and brother would be healed if they could give Scott this precious, ultimate gift of mercy. But the room where Blake sits with her cousin remains dark. Scott, whose last name we never learn, remains a cipher.

It pains me to write these sentences. I have written extensively about the need for criminal justice reform, including the importance of appreciating that juvenile offenders are children and that no child should be sentenced to die in prison. But were I on the fence about these things, Scott’s case would not convince me. A former public defender, I have spent years representing people accused of horrible crimes. The vast majority of my clients are people I have come to believe are deserving of mercy and a second chance. But that is because I know them in three dimensions. I learned in the time we spent together that my clients were, as Stevenson likewise insists, better than the worst thing they ever did. But that heartfelt knowledge is hard to come by and even harder to explain to others. It is not clear to me whether Blake has this understanding of her cousin, but it is clear to me that if indeed she does, she has not explained it.