The Canyons, the Stars, and the Realm Beyond

Olivier Messiaen’s tribute to America

In the autumn of 1970, the New York arts patron Alice Tully sought to commission a piece of music commemorating the forthcoming bicentennial of the United States. She might have approached any number of American composers for the occasion, but she turned instead to Olivier Messiaen, arguably the most significant French composer since the death of Debussy. Messiaen had been to the United States before, for example in 1949, the year Leonard Bernstein conducted the American premiere of his mammoth Turangalîla-Symphonie. But writing an American work didn’t appeal to Messiaen all that much, and only after a fair bit of wining and dining and much cajoling on Tully’s part did the composer finally accept. There would be one important stipulation: Messiaen wanted to compose a paean to America’s landscapes, specifically the canyons of the West, photographs of which he had seen in a book. He had no interest in cities or skyscrapers. In photographs of Utah’s canyons, however, this devout Catholic saw nothing less than the handprint of God.

Born in 1908 in Avignon, Messiaen had a musical epiphany at the age of 10, when he gazed for the first time at the score of Debussy’s opera, Pelléas et Mélisande, with its luminous colors and diaphanous textures. Stravinsky and Bartók influenced him, as well, as did the musical traditions of Southeast Asia, India, and Greece. His studies led to the codification of seven “modes of limited transposition,” scales based on symmetrical groupings of whole-tone and semitone intervals. These modes would form the basis of Messiaen’s harmonic and melodic idiom.

Early on, he developed a taste for lush surfaces and the grandiloquent gesture, but eventually, his music grew spikier, more difficult. Like so many other 20th-century composers, he had an extended, fruitful dalliance with serialism. What set him apart from every other modernist was his lifelong obsession with birdsong. “Birds are my first and greatest masters,” Messiaen once said. They “always sing in a given mode. They do not know the interval of the octave. Their melodic lines often recall the inflections of Gregorian chant. Their rhythms are infinitely complex and infinitely varied, yet always perfectly precise and perfectly clear.” Traveling all over France in search of birds, Messiaen meticulously recorded what he heard, later incorporating these lines into his music, doing so in more or less literal fashion—no hazy impressionism for him.

Messiaen had the rare gift of synesthesia—musical tones and certain key signatures evoked for him the most vivid array of colors. And in every sound, every color, Messiaen felt the presence of the divine. He often used the phrase “theological rainbow,” and said that, ideally, his art would be the sonic equivalent of a stained-glass window radiant with a flood of sunshine. I sense this quality most intensely in the solemn, hypnotic pieces he wrote for the organ: Le Banquet céleste, L’ascension, La Naivité du Seigneur, Les Corps glorieux. Perhaps it’s because of the instrument’s churchly context, or the knowledge that Messiaen played the organ at Paris’s Church of the Holy Trinity every Sunday for more than six decades of his life.

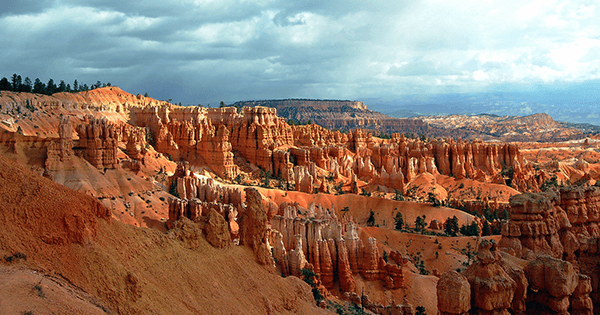

At any rate, given his keen synesthetic powers, how could Messiaen not have been enchanted by the terrain of southern Utah—all those rock formations lit up in brilliant orange and red? It was one thing to see these landscapes in a book, quite another to experience them firsthand. And though Messiaen began working on Tully’s commission in the summer of 1971, only after journeying to Utah the following spring did his massive, magnificent work—Des canyons aux étoiles … (or, From the Canyons to the Stars …)—take shape. Messiaen and his wife, the pianist Yvonne Loriod, first flew to Salt Lake City, then made the difficult four-hour drive to Bryce Canyon. There Messiaen beheld

the greatest wonder of Utah. It is a gigantic amphitheatre, with fantastic, red-orange and purple rock formations shaped like castles with square and bulging towers, natural windows, bridges, statues and columns—entire cities, with from time to time a deep and dark hole. This forest of petrified stone and sand can be admired from above (the altitude is about eight thousand feet) or you can go down to the bottom of the gorges and walk under this fairy-like architecture.

This is precisely what Messiaen and Loriod did, descending into the canyon alone. Today, our National Parks are flooded with hordes of selfie-snapping tourists, but Messiaen encountered quite a different setting in the spring of 1972:

It was marvelous, grandiose; we were immersed in total silence—not the slightest noise, except for the birdsong. … We took walks in the canyon for more than a week, and I transcribed all the birdsongs. I also took note of the fragrances of the sagebrush (an aromatic plant growing there in great quantity) …

The couple also went to Cedar Breaks, an unspoiled amphitheater of variously colored rocks through which the wind howled, and Zion Park, which he likened to a celestial Jerusalem. What a contrast this world must have been to the spare, humble, Montmartre apartment that he and Loriod shared!

The 12 movements of Des canyons aux étoiles …, completed in 1974, are grouped into three parts, the culmination of each being a striking depiction of a different site: Cedar Breaks, Bryce Canyon, Zion Park. The work is filled with complex and beguiling birdsong—the oriole, robin, steller’s jay, mockingbird, and wood thrush all have their eloquent say. This is music of violence and transcendence, lyricism and jagged rhythms, music constructed of monumental boulders of sound. It is also profoundly religious music in which dissonance predominates but consonance startles and amazes—the Bryce Canyon passages in E major, for example, and the throbbing, ecstatic A major at the end of the work, depicting the ascension to the heavens (thus, the ellipsis in the work’s title). I sense, above all, the feeling of spaciousness—of earth and sky and celestial realm—from the first notes: Messiaen’s description of an empty desert landscape, with a solitary horn call and a twinkling response from the xylophone, piano, and woodwinds. The percussion section is crucial throughout, with important roles for the xylorimba, glockenspiel, eoliphone, which produces the sound of the wind, and geophone, or sand machine. There are also extended solo parts for the French horn and the piano, writing that is both florid and fiendishly difficult.

Last Friday night, I heard Des canyons aux étoiles … played by the United States Air Force Band. The conductor, David Robertson, the long-time music director of the St. Louis Symphony and one of our most impassioned champions of contemporary music, has this music coursing through his blood, and the performance was outstanding. Messiaen’s mesmeric work came gloriously alive in the cavernous setting of Washington’s DAR Constitution Hall. But this performance had an added dimension. Photographer Deborah O’Grady spent parts of two springs taking images and video of the very sites that had captivated Messiaen—these were projected upon a screen behind the musicians, with the stage lit up with colors corresponding to those invoked by the music. O’Grady’s evocative photographs are full of life and movement, giving us an immediate sensation of being there in the West. And there is a political subtext to her work, as well; seeing the pictures, we are reminded of the grand ecological crisis facing us today. Still, as my eye flitted back and forth between image and stage, I couldn’t help wondering if this visual dimension were detracting from the musical experience.

I remember attending a concert many years ago when Leonard Slatkin led the National Symphony Orchestra in Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. That night, each of the paintings that inspired the different movements of Mussorgsky’s work, by the composer’s friend Viktor Hartmann, was projected as the music played. The trouble is, Hartmann’s pictures seemed to me banal, simplistic, uninteresting, inferior in every way to the music. This is what inspired one of the most canonical pieces in Western music? I wondered, bemused. The paintings weren’t just superfluous. They were a distraction. O’Grady’s visceral, thought-provoking photographs and videos are in a different league, yet once again I found myself distracted. A work as supremely complex as Des canyons aux étoiles … requires complete engagement from the listener: something approximating a meditative state in order to contemplate the work’s mysteries. Yet every time I looked at the screen, or noticed that the stage was aglow with red or orange light, my imagination was in turn diminished. Multimedia may be all the rage, but for me, the ideal way to experience Messiaen’s work in all its glory is to engage with it the way the composer himself encountered the canyons of Utah: as free of mediating influences as possible.