The Cloistered Books of Peru

A convent in the Andes is home to a treasure trove of rare, and possibly unique, early volumes

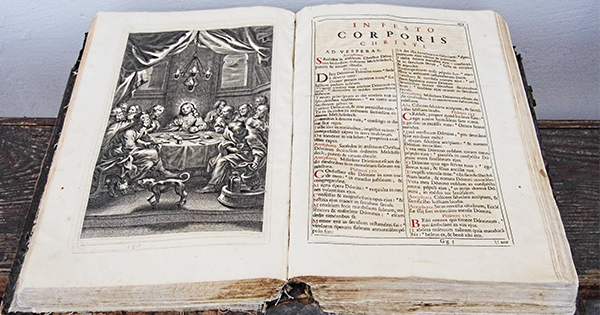

In our digital age of e-readers and same-day delivery, it’s worth remembering how much blood and sweat used to go into the distribution of the written word. Consider the journey of a book I’ve had the rare privilege to examine, a Catholic breviary published in 1697. A call-and-response worship device, bound with wooden boards and covered in tooled leather, it is printed in bold blacks and reds and features lush illustrations throughout. The massive tome measures 18 inches high, 12 inches wide, and six inches thick, and weighs in excess of 22 pounds. Not an easy book to carry around. Yet, not long after its publication, someone did carry it—all the way from its publishing house in Antwerp, down the thousand miles through Europe and the Iberian Peninsula to the city of Seville. There it was loaded onto a boat and transported down the River Guadalquivir to the Atlantic loading port of Sanlúcar, where, along with thousands of other books, it began a month-long journey to the Caribbean Sea. Arriving at one of the islands of the Lesser Antilles, it was offloaded and placed aboard a smaller vessel for transit through pirate-infested waters to the port of Nombre de Dios (later Portobelo), which lay on the Atlantic side of the Isthmus of Panama.

The next leg of the journey, crossing the Isthmus itself, a mere 30 miles at its narrowest point, was a cursed ordeal. The shorter of the two possible routes took only four days but wended up into the mountains and along the Isthmus’s spine on a perilously rugged and narrow path. The longer route, known as the Gorgona Trail, was safer but required two weeks of hard travel down the Atlantic coast to the Chagres River, a muddy mess harboring dangerous reptiles and malarial mosquitoes. Adding to the difficulties of either itinerary was the presence of pirates and fugitive slaves whose livelihood depended on plunder. Both routes led to the city of Panama, on the Pacific side of the Isthmus. From there, the breviary and its companion books were loaded onto galleons for the 1,400-mile voyage down the Pacific coastline to Lima—the City of Kings and, for the legions of Spaniards seeking their fortunes, the major port of arrival in South America.

Once in Lima, where they often spent some time in the collections of private owners, the books eventually made their way south some 630 miles, probably carried by mules through the mountains, to the southern city of Arequipa. Some of them may also have been shipped down the coast to the port of Islay, then hauled uphill another 70 miles by mule or oxcart to reach the city. In all, the breviary, which I could barely lug from one room to another, and whose precise route to the New World we can, of course, never truly know, traveled about 9,000 miles to reach its destination.

It resides there still, in the Convent of the Recoleta, perched high above the Chili River in Arequipa. The city was founded in 1540 by the Spanish conquistadors, though found is perhaps the better word. When the armored and sturdily mounted Spaniards first clattered onto the site, they encountered a series of riverside villages set among the Andean foothills. In due course, they created a prominent colonial center of civic buildings, churches, and mansions, all in the heavy stone architecture of Old Spain that nonetheless incorporated an exotic mix of New World décor. Carved depictions of Indian warriors and maidens mingling with cowled European saints bedeck white-stone façades and pillars throughout the city, somewhat to the confusion of modern-day tourists. The days are mostly sun-filled and, at an elevation of 8,000 feet, Arequipa—known in Peru as the White City—shimmers in the clean mountain air.

The Recoleta, established in 1648, was built as a retreat not for pious women but for the exhausted missionaries who spent harsh decades in the mountains and jungles of Peru pursuing the conversion of new subjects to the Catholic faith. Its bougainvillea-covered stone walls enclose four calm and sheltering courtyards, each featuring thick, green lawns, handsome fountains, and statuary. The building’s low-slung structure contains meeting rooms and private cells ideal for recuperation and reflection. As in most Latin American convents, there is also a library. The Recoleta’s holds some 20,000 volumes, and I am its librarian.

Some of these books show the ravages of their journey. Covers are broken; pages are ripped, disintegrated, or missing. Before 1800, a single complete work often consisted of multiple volumes, and in many cases our collection contains only portions of those works. I sometimes wonder where they parted from their siblings. Did the missing volumes bounce off a muleteer’s cart crossing the Pyrenees, the Isthmus of Panama, or the Andes? Did they decompose somewhere at the bottom of the Atlantic or Pacific Ocean? More than a few of the Recoleta’s volumes show some degree of water damage. Saltwater or fresh? Despite these hazards, many historic books in our collection remain in a condition that any rare-book dealer would rate “fine.” Even now, this never fails to astonish me. How did those Spaniards do it?

The founding of Arequipa was, of course, only a small part of the 16th-century Spanish conquest of the Americas. The conquistadors’ arrival was tumultuous and lawless, but in their wake followed impassioned men of God who believed they were bringing order and civilization to heathens in need of salvation. They came with the backing of the Spanish Crown, which, while countenancing much of the conquistadors’ rapacity, remained mindful of the spiritual needs of its new subjects. Many missionaries who answered the call hailed from Spain’s educated elite. They sought first to build a society of Christian believers, and within it, a place for high Spanish culture.

Such men needed books, and the Spanish Crown concurred, exempting virtually all printed matter from the taxes imposed on other goods—and the flow of books, substantial from the start, quickly grew to meet demand. Books were so highly valued that their prices often doubled upon reaching American ports, prompting illiterate sailors to tuck volumes into their gear for use as currency upon arrival. The first modern historian of this book exodus was Irving Leonard, whose Books of the Brave (1949) draws in part upon records kept by the office of the Spanish Inquisition. He cites a 1601 record of a single vessel carrying 10,000 books westward from a harbor south of Seville. Many tens of thousands of these books had been meticulously identified by order of the Inquisitorial censor, allowing us an invaluable glimpse into the history of reading.

The flood of books into the New World was but a part of the intellectual fervor going on in Europe between 1450 and 1800, a period known as the Golden Age of Hand Printing. The production of printed works and books was the primary vehicle for this surge, ignited and sustained by Gutenberg’s invention of movable metal type, but also by the expanding production of rag paper, which resulted from advances in the burgeoning field of textile crafts. Enhancing the technical aspects of the production of books were efficiencies wrought by urbanization and the growth of trade. Books played a growing role in the acquisition of literacy and learning, particularly in the Reformation’s emphasis on the sacred text, as well as an ascending rule of law nurtured by stronger central governments, the revolution in science, and the rise of universities engendered by the Renaissance. Commerce surged across Europe, fostered in part by new intercontinental trade with and exploitation of the Americas.

The library of the Recoleta is not a specialized collection of the kind that might be found in a monastery. Of its 20,000 volumes, only 3,500 date from the Golden Age, but these nonetheless form a microcosm of Renaissance Europe—or more accurately, Catholic Renaissance Europe, since the censorious hand of the Inquisitors prevented almost all dissenting ideas, mostly arising from Protestant Europe, from reaching the New World. Martin Luther and John Calvin, for example, are not represented. Even so, just 40 percent of the Golden Age books in the collection are religious texts. The balance is made up of a sizable body of works on civil and canon law, a good number of dictionaries and grammars, and a representation of the Greek and Latin classics, along with works of philosophy, history, economics, science, and literature. In the 16th and 17th centuries, most books were published either in Northern Europe or Italy. Spain lagged behind in the book trade until the 18th century, and for that reason, only the Recoleta’s later holdings come primarily from the Iberian Peninsula.

The library is not the only collection of old books in Arequipa, but of the city’s six historic libraries, only the Recoleta’s is open to the public, albeit in a limited sense. Visitors may enter and look at the books on the shelves, but they cannot touch. In the 1970s, the Recoleta turned the greater part of the original complex into a museum, featuring displays of pre-Columbian artifacts, colonial art, and Catholic art and décor. One popular room displays exotic stuffed animals, another is devoted to Amazonian culture, and yet another to missionary activity.

But the museum’s major attraction is the library, the likes of which the visitor is unlikely to see anywhere else in the world. Housed in a long room with floors, walls, and shelving of dark, rich wood, it is ringed by a second-floor balcony of books on three sides and tall windows on the fourth. The balcony is accessible by three graceful staircases, all of expertly carved wood. Overhead, six large skylights allow for reading, provided that you situate yourself properly. The library even smells nice—a soothing blend of books, leather, wood, and wax. Upon entering, most visitors stand quietly and simply look.

In 2002, having retired after many years as a librarian at the University of Iowa, I moved with my husband to Arequipa, where he had served in the Peace Corps in the late ’60s. We now spend our days caring for Golden Age books in an 18th-century workshop of stone walls and floors, adjacent to the Recoleta’s library. Obtaining the positions for my husband and me was a difficult, drawn-out affair. Fortunately, over the years my husband had maintained contact with Arequipa residents of social distinction. One of these, Alvaro Meneses, is a still-vigorous man of wide interests. He had been a banker, lawyer, and diplomat, and now, with a little persuasion, had decided to become a librarian. Of course, he would need an assistant—specifically, one with my technical training and experience.

So began his campaign to get us in—a process clouded by suspicion and further complicated by our status as foreigners. Thievery of all kinds abounds in Peru, and as a result, most Peruvians are cautious, including the padres of the Recoleta. Museums, churches, and libraries are particularly vulnerable. In December 2002, armed bandits, aided by professional bookmen giving direction by cell phone, robbed the Franciscan Convent of Ocopa, in the mountains of central Peru, of its most valuable early books. Likewise, the National Library of Peru over the past decade has lost at least 1,000 of its early books to professional thieves, often abetted by colluding employees. And local suspicions are further elevated by regular news reports of skirmishes between Yale University and the government of Peru over the treasures of Machu Picchu—some 35,000 shards of pottery and other artifacts that are slowly being returned to Peru after having been lent to (or, depending on your view, plundered by) American explorer Hiram Bingham, who opened Machu Picchu to the world in the early 1900s.

Alvaro set about persuading the padres in ways I never fully understood. I know there were phone calls, cocktails, and dinners. I suspect there were reminders of old family loyalties, of favors done, of the importance of reciprocity. Before launching his campaign, Alvaro’s daily habit had been to attend early Mass in churches throughout the city, but now he changed this pattern to attend only at the Recoleta. “How can they mistrust such a pious man?” he explained to me. And pious though Alvaro may be, today’s padres were as resolute in protecting their books as their predecessors had been for the past 360-odd years. Their skepticism was further heightened by their lack of understanding of what we wanted to do.

Librarians in North America have a long and laudable history of freely offering their holdings—printed and digital—to the public. Their resolve has spread through the United Kingdom and much of Europe, but, generally speaking, the momentum has not reached the rest of the world, and certainly not Latin America. On the contrary, there exists here a strong tradition of withholding books from those who might be ill-intentioned or careless—the historic echo of a time when books were considered objects of veneration that should go unsullied by use. Some religious libraries in Peru bar outsiders completely. Others, including the Recoleta, allow entry, but anyone seeking to use its holdings must come with scholarly credentials and proper referrals. Normally, they must seek permission well in advance.

The padres in charge of these institutions lack the resources to assist any but the most resolute researcher. The catalogs of holdings are sketchy at best, and many of the books are shelved in no discernible order. No extra staff watches over researchers using rare and delicate materials, an unbending requirement in nearly every library in the world. The guardians of these books know from centuries of experience that the impassioned scholar or bibliophile is also the most likely thief, and usually the most cunning. Perhaps most important, the religious institutions of Peru have serious competing needs, and assisting outside scholars is not the most pressing.

Over the past century or so, librarians and bibliographers across much of the globe have spent a great deal of time identifying and promulgating the location of extant books printed during the Golden Age. But the effort has barely reached Latin America, where thousands upon thousands of early books, like those in the Recoleta, have gone undocumented—precisely the problem I hoped to solve by cataloging and making public the existence of these volumes.

Librarians almost everywhere report the contents of their collections to an institution called the WorldCat, a massive database of more than two billion items in all alphabets and written languages. On the whole, it has been remarkably successful in clarity and scope, employing a uniform system of description that allows readers to locate books by author or subject the world over. Were there no such catalog, anyone desiring a specific book or source of information could find it only by extensive travel to relevant libraries and collections, as was the practice of scholarship in the not-so-distant past. The WorldCat is well established, adequately funded, and stands as an essential tool for the contemporary scholar. My fanciful notion was to catalog each of the Recoleta’s Golden Age books using the universally accepted standards and to enter the descriptions into the WorldCat.

For more than a year after his daily Mass, Alvaro wined and schmoozed. Meanwhile, I wrote formal proposals and solicited letters of support from important people. Money helped, too. Arequipa is home to the Cerro Verde Mining Company, which owns one of the world’s largest copper mines. It just so happened that a friend of Alvaro’s headed the company’s public relations department; he offered Cerro Verde’s financial support. In 2007, the Franciscan padres finally opened their doors to us. They assigned us the premodern workshop adjacent to the library; Cerro Verde funded its remodeling and equipped us with computers and access to the Internet. The local University of San Pablo provided technical expertise and student assistance to perform data entry and heavy lifting. Things started to come together.

Arequipa is an excellent natural locale for book preservation, with a stable and moderate climate of the sort that most modern libraries attempt to achieve through artificial air-control systems. The altitude is inhospitable to most species of vermin that eat books; and mold, which can destroy whole collections in short order, is not a factor in this semi-arid setting. Thus, many of the Golden Age books were in remarkably good physical condition, allowing me to move on quickly to identifying the contents of the collection.

At this point, however, my confidence began to waver. How could a couple of retired people with a scattering of assistants do this job properly? And if it ever got done, what was to happen to all the Golden Age books residing in the other historic libraries of this city? By now, I was also beginning to learn about the many thousands of similar early books hidden away in religious libraries all over Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia—in short, all of Latin America. What was I doing?

With a perhaps irrational exuberance, I nevertheless began the task, fueled as I was by images of the hearty conquistadors, padres, and fortune seekers who spent enormous energy getting these books here in the first place. As the work progressed, however, I couldn’t help but wonder at their motivations. Sure, I can understand the desire to carry a Bible for spiritual succor or a long work of adventure fiction for entertainment—gratifying possessions to have on hand when separated from civilization for a long period. But the existence here of some unusual and peculiar works is perplexing. For instance, one of the finest examples of Golden Age printing is a three-volume set, Ezechielem Explanationes, by Juan Bautista Villalpando, published in Rome between 1596 and 1604. This oversize set, the whole comprising 1,888 pages, is an imagined reconstruction of the Temple of Solomon. The author was an architect, a mathematician, and a Jesuit scholar who, under commission from King Philip II of Spain, worked for 10 years with the Book of Ezekiel and other sources to painstakingly recreate an imagined temple in exactitude—every wall, patio, and roof. His Explanationes presents 27 large fold-out plates showing detail down to the individual bricks. The work stands as a basic source for determining ancient Hebrew weights and measures and is acknowledged as having deeply influenced European Baroque architecture. The strong rag paper of our copy at the Recoleta is in excellent condition, yet creamy colored and pure, almost as if it just came off the press in Rome. The vellum binding is still holding strong. What is it doing here in a humble Franciscan convent at the foothills of the Andes?

Also consider the Libro de Tientos by Francisco Correa de Araujo, a Spanish organist and music theoretician. A collection of his musical compositions and treatises on theory and performance practice, it is a seminal work in the study of music. Correa’s essays have been reprinted and his compositions recorded in hundreds of editions and formats over the years, and his work is still widely studied and performed today. The collection in its original format is rare, with only three other copies reported to exist in the world’s libraries. In time, it will be known that it also exists at the Recoleta in Arequipa, Peru. Why it exists here remains a puzzle.

In addition to such oddities, there are many volumes of Roman canon law and the Corpus Juris Civilis, the basis for all modern civil law, issued in the sixth century by the Byzantine emperor Justinian. There are a number of sets of the writings of the Church Fathers and other Catholic scholars, many in such good condition that they have obviously never been used. I can only suppose that in their day, the very fact of their existence, standing on the shelves as tall and firm as soldiers, was sufficient to the intent—as the missionaries saw it, creating a European civilization out of a world of savages. Works by Cicero, Horace, Ovid, Homer, and other classical authors show moderate-to-heavy use. Early grammars and dictionaries of Greek, Latin, and Spanish were in demand. Many devotional and spiritual works bear generations of fingerprints.

I bump into other popular curiosities. There is a 1614 edition of Girolamo Menghi’s Flagellum Daemonum, a widely used manual on exorcism, handled so heavily that it is falling apart and lacking pages. Most of the volumes on Catholic mysticism have been well pored over. Within the collection are seven different early editions of The Mystical City of God by the Venerable Mary of Jesus of Ágreda, a cloistered nun from Spain, who, between 1620 and 1631, supposedly used bilocation (also known as astral projection) more than 500 times to teach the Catholic faith and rituals to the Jumano Indians of West Texas and New Mexico. It is reported that when the Spanish explorers arrived in the northern regions, they found these natives turned out with crosses and rosaries, awaiting baptism.

To date, we have cataloged into electronic format about 60 percent of the collection and are on course to complete our original proposal to catalog all early books in about two years. The most obvious next step would be to undertake similar projects in the other five religious libraries in Arequipa. I have examined all the collections (or their catalogs) and have determined that, including the Recoleta, some 20,000 early books reside in the city. Unfortunately, they all belong to different branches of the Catholic hierarchy, so my success in gaining access to the Recoleta’s collection will not automatically open other doors.

And what of the many religious libraries and collections elsewhere in Peru? Some of them have at least recorded and dated their holdings and provided counts of their size to the general public. The Jesuits—creators of a wide-ranging educational effort that was active during the early colonial period—were expelled from Latin America in 1768, but their collection of more than 4,000 volumes remains at the National University of San Antonio Abad in Cuzco. The Franciscan Library of the Descalzos in Lima holds another 5,000 early printed works. The National Library of Peru reports 4,000. Another five libraries with significant holdings, each ranging from 10,000 to as many as 25,000 volumes, provide dates of publication very spottily, if at all, making it impossible to determine how many of their books were published before 1800. If one totals up all of these reported figures, the number of Peru’s pre-1800 holdings approaches 76,000.

There are probably many more. Various churches and other institutions are unable or unwilling to publicize themselves. I recently spoke to the director of academic and special libraries of the National Library of Peru. She was making a first attempt at a census of the country’s libraries and guessed that up to 50 such libraries may exist, some doubtless within the crumbling colonial churches scattered throughout the mountains, high plains, and jungles. Many of these structures are still functioning but are in a state of near ruin. No one really knows how many libraries there are in Peru, much less how many books.

The books sitting quietly in Latin America, then, may well be the last of their kind. During the Second World War, the pillaging of Warsaw by the Nazis resulted in the loss of more than 16 million volumes, and the firebombing of German cities by Allied planes wiped out an estimated one-third of all books in German libraries. Recently I conducted a random survey of 100 books in the Recoleta’s collection, checking them against the WorldCat and other national and regional catalogs, and achieved a striking result: 18 are held in the same edition in only two or three other libraries in the world, six survive in only one other library, and four of the books are unique, that is, they were not reported to exist in the same edition anywhere else. It would be unwise to conclude that four percent of the 76,000 pre-1800 books residing in Peruvian libraries–or about 3,000 volumes—are unknown anywhere else in the world. That number seems high, but the count of unique books is likely to be substantial. And some of them—if and when brought to light—may well turn out to be unusual items eclipsed for centuries.

So what can be done about all these fine books hidden away in the remote religious institutions of Peru? In countries around the world, the identification and promulgation of the location of books in library collections ordinarily falls under governmental purview, specifically to the national library of the country in which the books reside. It has been a huge task, but during the past century or so, the national libraries of most wealthy countries have done this.

The Peruvian government, with comparatively meager resources to draw upon, has nonetheless directed considerable energy and funding toward uncovering, preserving, and elucidating the country’s cultural heritage, focusing in particular on its pre-Columbian past. The private sector has joined in the effort. There is little interest here in devoting limited funds to cataloging books printed long ago and far away.

Yet elsewhere, huge projects are ongoing. In 2014, the Vatican initiated a program to scan and provide worldwide access to each of its 82,000 manuscripts, comprising 41 million pages at an estimated cost of €50 million over 15 years. The Endangered Archives Program of the British Library has committed, for the period of 2004–2016, £10 million to preserve various archives from all areas of the world, mostly through digital reproduction. In the United States, the NEH has an annual budget of around $420 million, of which about $20 million goes to promulgating electronic indexes and scanning full texts of written and visual materials. In the 1990s, the Consortium of European Research Libraries began an ongoing effort to seek out, identify, and create elaborate descriptive records for all hand-printed materials created between 1450 and 1830. The consortium includes some 200 major libraries in Europe and North America, but has made no advances in Latin America. Most large libraries of the wealthy countries of the world are carrying out extensive programs to convert their own materials of specific interest into digital format. The caretakers of these collections concur with the words of the esteemed Monsignor Cesare Pasini, the director of the Vatican project, that it is “a service that we provide all mankind.”

But you don’t need thousands of librarians to record and announce to the world that these books are here. A well-planned project with a capable structure and adequate support and a few librarians can do the job. There is a new generation of church governance in Peru, whose members understand the significance and rewards of technological advances. With the proper backing, I hope that the padres will follow the precedent of the Vatican and open their doors for the good of all mankind.