The Corals and the Capitalist

The key to avoiding an ecological catastrophe might be found in the wealth of nations and the spirit of innovation

During winter break four years ago, our family rented a condo on the beach in South Padre Island. Stretching along the Texas coast, it’s the world’s longest barrier island, infamous for its spring break debauchery. But in the winter, it’s a low-key getaway of soft sand and seashells.

Reclining on a lawn chair on our rental’s porch, with the sound of the surging waves as background music, my 17-year-old tech-savvy son, Ben, lifted his head from his cell phone and said, “SpaceX just launched a GPS satellite into space for the Navy. First one.” He gestured south in the direction of Boca Chica Beach, where Elon Musk’s SpaceX had built a behemoth rocket-launch site.

“Everything go okay?” I asked.

“Perfect,” he said.

“You know,” I said, hoping to catch my son’s fleeting teenage interest, “there’s going to be an X Prize for saving coral reefs.” During a recent reporting trip to Florida to cover the future of coral reefs, I’d learned that the nonprofit X Prize foundation, which offers cash awards for technological innovation—including a $10 million purse for the first team to launch a reusable rocket into space—was looking to create a competition to save the coral. “No one thought a private company could send a spacecraft into space. Now, it’s a full-scale industry. So, they are going to try to monetize saving coral, in hopes it creates technology that can evolve into a business.”

Keith, my husband, was sitting at the sun-bleached breakfast table, his head similarly buried in his cell phone. But now he lifted his eyes from the addictive word game he’d been playing. “It’s called a market,” he said. “You create a market. That’s where innovation comes from.”

“No one has ever tried to use the free market to save an entire ecosystem before,” I said.

My capitalist husband smiled back at me before turning back to his word game. “So, we don’t know what’s possible.”

I rolled my eyes and snorted. His comments were precisely aimed at one of the major points of conflict in our otherwise healthy relationship, a chronic disagreement that I doubt we’ll ever settle. Keith believes wholeheartedly in the power of capitalism and the market to inspire creativity and move the world forward. He admits to capitalism’s imperfections, but he believes that no better system has ever existed to drive progress and innovation. “Find me one,” he says whenever the topic comes up.

I can’t. I’ve tried. And historically, he’s right. Since the advent of capitalism, the average human lifespan has grown by more than a dozen years, and two billion more people have been fed than scientists had at one time thought possible—to say nothing of capitalism’s role in creating the Internet, smartphones, satellites, and addictive word games. During our two-and-a-half-century experiment in capitalism, no authoritarian regime, no communist or socialist economy, no religious rule has been the source of as much creativity. And, on a per capita basis, no other system has been responsible for as much pollution, either.

I concede that a competitive market might be an unrivaled source of innovation. But at what cost? Markets are about the consumption of resources, not about their preservation or restoration. Businesses think in the short term, in quarterly reports. The damage to our planet has been institutionally excluded from the calculus of success. This is what economists call “an externality,” a consequence of business practice that isn’t included in the cost of a good or a service. For as long as there have been businesses, there have been externalities. And now, with climate change breathing its hot air down our necks, we are poised on the edge of a global crisis. Some have taken to calling our current version of capitalism “late stage,” in which inequality overwhelms innovation.

The coral reefs are predicted to be among the first casualties of the climate crisis. This is a story I’ve immersed myself in ever since that reporting trip to Florida four years ago. (The work led to my publishing a book on the subject in 2022.) Coral reefs have a disproportionate influence on the oceans, and our economies. They are home to a quarter of all marine species, estimated to be between 500,000 and a million in total. Not individuals, but species. Coral reefs account for around $2.7 trillion in economic value annually and provide as many as a billion people with their primary source of protein. Coral reefs are also the most effective barrier against ever-stronger storms, diffusing 97 percent of a wave’s energy before it reaches shore.

Despite their plantlike appearance, corals are animals. But they are animals with a superpower: the ability to form an alliance with symbiotic algae that live embedded in their digestive tracts. The algae photosynthesize, mixing carbon dioxide and water with the sun’s energy to form sugar and oxygen. The algae then feed 90 percent of the sugar they make directly to the coral. This sugar is the fuel that gives the coral the power to build the great calcium carbonate reefs of our seas.

Unfortunately, this superpowered duo has, as heroes must, a tragic flaw. For reasons that are still unclear, when the temperature rises by just a couple of degrees for a few weeks, the algae and coral alliance dissolves. The algae depart with their color and their sugar. This leaves the coral bleached and with fuel tanks on low. If the heat wave persists, the corals die. Large-scale bleaching events were unknown before the 1980s. Now they happen almost continuously. Half the corals in the world have already been bleached, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts that by 2050, 99 percent of the world’s coral reefs could be gone.

It’s probably not surprising, given how immersed I am in these facts, that I suffer from climate anxiety. I obsessively doomscroll the weather app on my phone, following storms as they pinwheel across the Atlantic Ocean and into the Caribbean. I watch wildfires pop up across the western United States, running up the coast to Alaska and northern Canada. I’m one of those people whose email lists serve up a daily dose of flooding and insect-borne disease.

My doomscrolling also serves up reports of failed attempts by governments to bring down the planet’s runaway fever. After 26 international climate conventions, nothing like the global plan we need to keep our planet and its ecosystems healthy has emerged. Since my book was published, I have frequently spoken to audiences about the plight of the coral and the connection to climate change. I’m so tired of being asked, “What individual actions can you suggest to protect the coral?” The question itself does nothing but foist guilt on us all. The truth is, our individual actions can never make a big enough difference. We’re at the point where systemic change is the only viable solution, and yet, systemic change affecting a system as big as our atmosphere feels far beyond our grasp. However, we did grab it once. And that knowledge keeps me from sinking into despair.

January 1, 1989, rang in not just a new year but also the implementation of a historic agreement. Called the Montreal Protocol, it was the first and only global environmental treaty to have a long-standing effect on the health of our planet’s atmosphere. The nations of the world, without exception, agreed to ban the production of chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, a class of molecules used for refrigeration, insulation, and aerosols, proven by scientific studies to be dangerous to life on Earth. In the environmental community, the Montreal Protocol is often held up as a beacon: as an example of how we can cooperate and come to an agreement when it really matters. Contrary to the prevailing trope, however, the beacon was lit by a different fuel than humanity’s collective sensibility.

Five years before the Montreal Protocol was signed, British scientist Joe Farman was working in a field lab on the edge of Antarctica. His expertise was measuring atmospheric gases, and he noticed a strange decrease in one of them: stratospheric ozone. For years, he had been measuring the same gases using the same sky-viewing spectrophotometer, and he’d never seen anything like this dip. In fact, the instrument Farman used was so old that he had taken to wrapping it in a quilt to steady its temperature, as if it were an elderly relative. Maybe the trusty spectrophotometer had finally reached the end of its life, Farman thought. So he put in a request for a replacement. But when the new instrument arrived, the ozone measurements were still uncomfortably low. The problem wasn’t with the machine; it was with the ozone.

Ozone, a molecule made up of three oxygen atoms, is concentrated in the stratosphere nine to 15 miles above sea level. There, it shields life from the sun’s ultraviolet light, which can damage DNA and lead to cancer and cataracts. Following Farman’s discovery, atmospheric chemists brought together disparate lines of evidence proving that the culprits thinning the ozone layer, popping apart ozone molecules like needles bursting bubbles, were industrial CFCs. A single chlorine atom in a single CFC molecule could destroy as many as 10,000 ozone molecules.

As the situation entered mainstream consciousness, the thinning ozone, which was concentrated in a roughly circular patch of stratosphere near Antarctica, was dubbed the ozone hole. There’s been speculation that something about that term played a role in the rapid response by the world. The word hole implied a physical void or a rift in a protective coating. We humans fear holes, which are dark, unknown places. Holes are dangerous. Add the clinical and unfamiliar descriptor ozone to the word hole, and you’ve got a scary-sounding and very effective bit of branding. The response becomes one of reaction: “Let’s fix this, and now.”

But it was more than branding. When the ozone hole was discovered, the United States was the world’s largest producer of CFCs. The bulk of that production was from a single chemical company, DuPont. DuPont estimated that CFCs contributed $8 billion to the U.S. economy and employed 200,000 people. In response to calls for limiting CFC production, DuPont contended, as the fossil fuel industry has for carbon emissions, that limits would result in unacceptable costs to the economy.

But as early as the 1970s, CFCs hadn’t been all that profitable for DuPont. Prices had leveled off and been undercut by volume sales to large customers. DuPont chemists had already been researching alternatives to CFCs and had some promising—and potentially more profitable—ideas in the cooker.

When the international community clamored for a solution to the ozone hole, DuPont saw an opportunity. The company was farther along in the development of refrigerant substitutes than its competitors. A ban would give it a market advantage. Meanwhile, by renouncing CFC production, DuPont could shape the perception that it was a good corporate citizen. In a three-week period in March 1988, DuPont’s chairman, Richard Heckert, shifted from saying that “there is no agreement within the scientific community on the potential health effects of any already observed ozone change” to issuing a company statement that “DuPont sets as its goal an orderly transition to the total phase-out” of the most damaging CFC products. It was a head-spinning turn. But really, it wasn’t the science or collective recognition of the environmental situation or some sort of morality or even good branding that catalyzed the first global environmental treaty. It was good business. The Montreal Protocol was implemented less than two years later.

But that is where the parallels between the story of the ozone hole and the broader story of climate change diverge. For years, I held a belief that a Montreal Protocol could happen for carbon dioxide, that if the nations of the world became convinced of an obligation to protect our future from climate damage, an agreement could happen. And for a few shining months, the Paris Accords—negotiated by nearly 200 countries and adopted at the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference—seemed to be Montreal’s equivalent. Then, the agreement collapsed before it even got going. Why? Lots of reasons, of course. Climate change is a wicked problem. But one of the main reasons why the Paris Accords haven’t fulfilled their promise is that no ready market existed. And the branding sucked, too.

Back in the fall of 1992, the doors of an elevator in a beautiful old biology building on the campus of the University of Southern California slid open. A professor was already inside, waiting for the lift to continue up. He looked up at me and said, “You’re the new graduate student who does math, right?”

“I guess so,” I answered, confirming that I did have an undergraduate degree in mathematics.

“I have an interesting problem I’m working on,” he said, as the elevator rattled up a floor. “Would you be willing to give me some advice about some work I’m doing?”

I nodded but was somewhat stunned. How could a fully tenured professor need the help of a newly minted graduate student like me?

The professor was Dale Kiefer, an expert in photosynthesis, and he was trying to calculate how much carbon dioxide the ocean takes up from the atmosphere. Satellites had just been launched that were streaming back images of the oceans from outer space. For the first time, we could see from above the complexity of swirling eddies and winding currents. In places where more sunlight was used for photosynthesis, less of it was reflected back to the satellites. The oceans looked darker. Could we use this new satellite information to calculate how much carbon dioxide the oceans were sucking up through photosynthesis?

I joined Dale’s lab, and although I contributed only a small part to the answer, one was found. The oceans absorb about a third of the carbon dioxide emitted by the burning of fossil fuels. If it weren’t for the photosynthesis of microscopic ocean phytoplankton, the climate crisis would be a whole lot worse.

When I first began studying the flux of carbon dioxide between the atmosphere and the oceans, what was then called the greenhouse effect was well known, and defining the sources and sinks of carbon dioxide was critical. Then, about two years into my degree, Dale took a sabbatical in Italy to work at the Food and Agriculture Organization, a United Nations program assessing changes in aquatic populations in the face of the warming oceans. I took the opportunity to work there for the summer as well.

When I returned to the United States in the fall, I remember watching the news one night. The reporter said that there wasn’t a clear consensus about the “so-called greenhouse effect,” that not all scientists believed the planet was warming. I remember being very surprised to hear this assertion—because it wasn’t true. Before I had left for Europe, climate change was settled. When I was in Europe, climate change was settled. For my dissertation, the work I did every day, I was studying climate change. All the scientists I knew were certain the planet was warming because of carbon dioxide emissions. What was going on?

I blame part of the problem on branding. None of the terms—from the greenhouse effect to global warming to climate change—have frightened people or inspired action the way ozone hole did. Greenhouses are places of growth and beauty. Warming conveys a sense of swaddling and security. I once read a textbook that described the excess carbon dioxide in our atmosphere as an extra blanket. What’s more comforting than an extra blanket? Change is just plain ambiguous, leaving a person to wonder what to feel. Lately, the terms climate crisis and climate emergency have gained traction, but perhaps because of the earlier lukewarm triad, there’s still a dismissive edge, as with the word hysteria.

as an extra blanket. What’s more comforting than an extra blanket?

The disconnect, however, was more insidious than branding. Even as the scientific consensus on the harmful effects of carbon emissions crystalized, fossil fuel companies did a calculation like what DuPont had done in the face of the thinning ozone hole. What they recognized was that they didn’t have in the cooker newer, more profitable ideas for supplying energy; neither were they willing to walk away from huge investments in fossil fuel extraction equipment and leases. To protect their profits, the fossil fuel companies doubled down, launching a misinformation campaign about climate change that put the brakes on energy innovation and polarized the political and cultural landscape. (If you haven’t read Merchants of Doubt or seen the 2014 documentary based on it, they’re worth your time.) Both sides became more entrenched, and they remained that way for two decades.

But in the four years since my husband, my son, and I sat on that porch in South Padre, something has been shifting, and it has started not with governments but with consumers. All of us have realized that we have a say in what we buy, and millennials in particular have been demanding that companies recognize their role in the health of the planet. In August 2019, 33 so-called B Corp companies, including Unilever, Patagonia, and The Body Shop, took out a full-page ad in The New York Times. These businesses had undergone a new kind of certification to “meet high standards of social and environmental performance, accountability, and transparency.” The ad urged major companies like Amazon and Apple to make similar ethical decisions—to care for their workers and consider the environment. As an article in The Guardian noted, “The B Corp movement is gaining momentum as the climate crisis coupled with rising inequality has made business leaders question what success looks like in the 21st century.” As of August 2022, more than 5,000 B Corps in 85 countries and a raft of more than half a dozen similar sustainability certification frameworks have emerged.

Proposed by the United Nations in 2006, the designation ESG—or environmental, social, and governance—is an umbrella term for efforts companies make to ensure that their actions are responsible to the planet and its people, and that those who run them represent the diversity of the people who buy their products and services. ESG designation languished for about a decade until companies that had paid attention to their environmental, social, and governance effects began reporting increased profits and decreased risks. When ESG-rated funds leaped from $5.5 billion in 2018 to $20.6 billion in 2019, investors and CEOs had no choice but to take notice. Not long after, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission created its own ESG rating system, in effect giving a kind of market-based blessing to the value of sustainability in business.

But even as the concept that the planet deserves consideration in business gained traction, cheaters took advantage. Fossil fuel companies released ads showing their commitment to alternative energy while lobbying for additional extraction permits. The term greenwashing, describing practices in which companies falsely claim environmental responsibility, has been tracking ever upward.

With businesses at the very least making a show of being environmentally friendly—and at the very best, changing their practices to decrease their environmental footprint—pressure to do something at the government level has been mounting. Finally, in August 2022, the U.S. government managed to pass a sweeping bill, the Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA, which analysts say will start to slow the flow of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

The IRA authorizes the spending of $374 billion on clean energy and climate resilience over the next decade. (If that seems like a lot of money, consider that, by comparison, fossil fuel companies reportedly received $5.9 trillion in government subsidies in 2020 alone.) What’s most interesting to me is that the IRA follows the CFC model precisely, by trying to create a market that replaces technologies that cause carbon dioxide emissions with something more profitable. As Robinson Meyer recently explained in The Atlantic:

In order to stop climate change, experts believe, the United States must do three things: clean up its power grid, replacing coal and gas power plants with zero-carbon sources; electrify everything it can, swapping fossil-fueled vehicles and boilers with electric vehicles and heat pumps; and mop up the rest, mitigating carbon pollution from impossible-to-electrify industrial activities. The IRA aims to nurture every industry needed to realize that vision.

The bill puts pressure on the market in four ways, pulling a collection of levers (collectively called “industrial policy”) that prop up innovation, supply, demand, and protection. In terms of innovation, just as the SpaceX rocket was spurred by the X Prize competition, the IRA provides $11 billion for hydrogen energy and carbon removal hubs, places where new ideas for shifting to clean-burning fuels and carbon removal technologies can be developed. On the supply side, it subsidizes domestic mines that provide the metals used in batteries and underwrites factories that make solar panels and wind turbines. On the demand side, it provides substantial tax credits for new and used electric cars. And regarding protection, the IRA requires that a portion of those electric vehicles be produced in the United States for automakers to claim those credits—one of a slew of policies that benefit “made in America” products. If all goes well, carbon emissions are supposed to fall by 40 percent from 2005 levels by 2030, putting us two-thirds closer to reaching our Paris commitments.

Another big move came just a few weeks after the IRA was enacted. With a rare bipartisan vote in the Senate, the United States ratified the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol. For the first time in 30 years, the United States has agreed to limit hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), which, like CFCs, are refrigerants. HFCs have 1,000 times the greenhouse gas potency of CO2. Several market-based provisions made the amendment palatable. Businesses from countries without HFC limitations will be subject to international restrictions, and manufacturers have been preparing for the shift for a decade. Also, alternatives exist. Even conservative Senator John Kennedy of Louisiana signed on to the environmental plan. As a press release from his office concluded, “Formalizing America’s support for the Kigali Amendment will reduce greenhouse gas emissions, boost U.S. exports, strengthen America’s manufacturing industry, lower consumer prices and create more jobs for U.S. workers.”

Although HFCs might seem obscure, the Kigali Amendment’s significance is anything but. Scientists expect it to avert a critical 0.5 degrees Celsius of warming by the end of the century. A few more coral reefs might just survive.

My mind often drifts back to that sunny day in South Padre four years ago, when the plight of the corals was fresh in my thoughts and I tried to lure my family into conversation about my work by talking about the X Prize. “No one has ever tried to use the free market to save an entire ecosystem before,” I’d said.

“So, we don’t know what’s possible,” my capitalist husband had responded.

We still don’t.

The X Prize competition to “save coral reefs” was canceled before it even got off the ground, or more accurately, before it even went beneath the waves. The funding partner pulled the prize money. I heard a number of explanations why. First, each reef is unique, so tools general enough to apply to a global coral restoration industry seemed unlikely to emerge. Also, how do you define save if each reef is unique? Ultimately, the funding partner decided to spend its money locally, an understandable example of market protection.

Looking back over the past four years, I’m struck by how much has changed, and how far we still have to go. Despite the terrible branding and disinformation campaigns, inroads have been made in tackling the climate crisis, which has lodged in our psyche and crept into both our business practices and our policy—not an easy thing in the stubborn United States. But though I’m encouraged by the market-building features of the IRA, I don’t hold my breath that a Montreal Protocol for carbon emissions will emerge. It will take time for the IRA, if it does manage to build a carbon-free market, to take hold and spread. An inescapable conclusion from the tales of chlorofluorocarbons and carbon dioxide is that without a viable market, we won’t be able to escape the precarious deadlock that we’ve been in for the past 40 years.

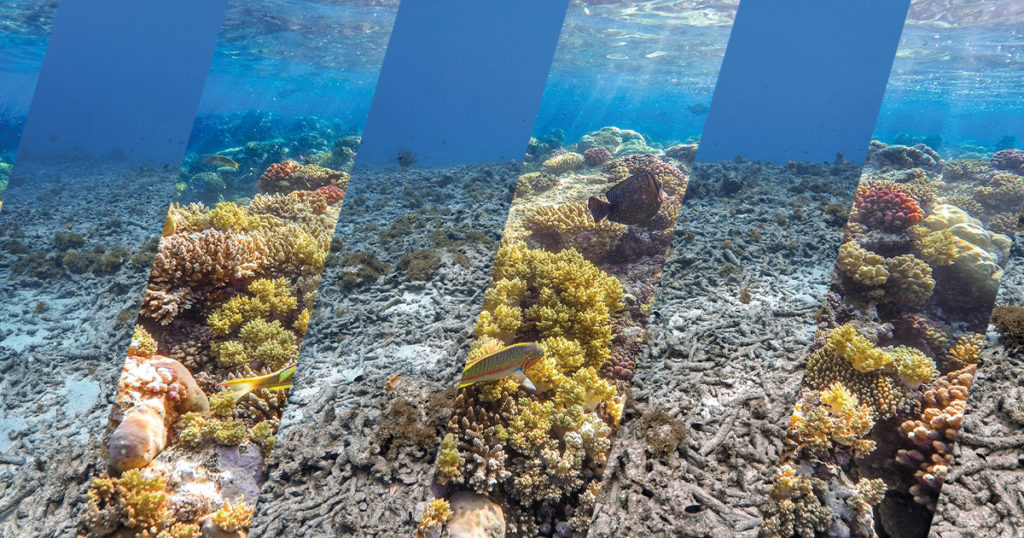

Meanwhile, by the time this essay is published, the next international climate meeting—COP27—will have been held in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt. Just offshore, in the Red Sea, is one of the world’s most diverse and, so far, healthy coral reefs. The very existence of those corals and others around the world depends on the decisions of policymakers and industry executives such as those gathering for COP27. If the world continues to avoid taking action, temperatures will continue to rise, seas will continue to swell, and hurricanes will throw their ever-more wrathful fury on our shores. All that threatens the coral will threaten us as well.

A few months ago, the X Prize foundation announced a new competition for saving coral reefs. The purse was doubled to $20 million with some funding partners in place and others yet to commit. I’ll be watching closely to see what happens. In this time of increased awareness and shifting business pressures, my husband’s words encapsulate what I’ve come to understand is the most valuable part of what capitalism has to offer: until we try, we truly don’t know what’s possible. Perhaps we’ve finally started trying.