The Uncanny Muse: Music, Art, and Machines From Automata to AI by David Hajdu; W. W. Norton, 304 pp., $32.99

What is art? What is music? Are they intrinsically human endeavors or can they be made by—not just with—machines? In The Uncanny Muse, his eighth book, David Hajdu traces a lineage of automated creative productions to answer centuries-old questions that have been thrust to the forefront once again with the recent explosion of artificial intelligence. A music critic for The Nation and a professor of journalism at Columbia, Hajdu is well positioned to ponder the philosophical stakes of algorithm-driven art, though the teacher in me wonders whether he is as tolerant of his students’ writing articles with ChatGPT as he is of the gamemaker who won the 2022 Colorado Art Fair with a work produced by the AI technology Midjourney. (I’m not.)

The title of Hajdu’s book borrows from the phrase “uncanny valley,” which, Google AI informs me, is “a psychological phenomenon that describes the feeling of unease or discomfort that people experience when they encounter an object that is almost human but not quite. The term was coined by Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori in a 1970 essay.” (When Hajdu directs ChatGPT to write a description of the history of itself “in the voice of David Hajdu,” the AI refers to its own “uncanny ability.”) Uncanny proceeds chronologically from an 1880s automated doll controlled by a magician to a 2023 AI doll controlled by filmmaker Baz Luhrmann. So much for progress. In between, Hajdu recounts tales of largely forgotten, and occasionally forgettable, moments and mavericks. The author of books on subjects as far ranging as the jazz musician Billy Strayhorn, early Bob Dylan, and comic books, Hajdu is a research GOAT. There’s Jane Heap, editor of The Little Review, who in 1927 curated the Machine Age Exposition, an exhibit of mechanical objects as art, and published futurist manifestos with the magazine’s founder and her life partner, Margaret Anderson. Frank Sinatra talks about how he learned to treat the microphone as an instrument, thus changing the course of recorded music. Hajdu even manages to find something obscure in the over-dissected Beatles catalog: Electronic Sound, an album recorded by George Harrison on the Moog synthesizer in 1969.

Occasionally the author gets a little lost in the weeds, and sometimes I wondered what exactly the throughline is from player pianos to Andy Warhol to electronic music pioneer Derrick May. The book can feel more like a series of interesting magazine articles than a cohesive narrative. Uncanny comes together in the end, though, especially in the chapter on the evolution of house and techno music. Hajdu is good at explaining complex subjects. I love the way he describes photography, which, as he points out, was once viewed as a mortal threat to art. “The camera transforms the visible in the name of capturing it,” he writes. Honestly, despite Hajdu’s best efforts, AI still confuses me. At one point, I began to wonder whether the whole book is a prank and written using ChatGPT. That’s when Hajdu admits that he did indeed use that gateway AI portal—but only for the preceding two paragraphs.

Hajdu doesn’t completely address the thorny, age-old ethical issues of replacing humans with machines or of using machines for nefarious purposes. He points out the creepiness of Luhrmann flirting with a doll of a young female, but he doesn’t mention that AI mannequins are already being sexualized in popular culture—or that a mechanical doll, unlike a human being, follows orders, doesn’t age, and won’t sue for sexual assault.

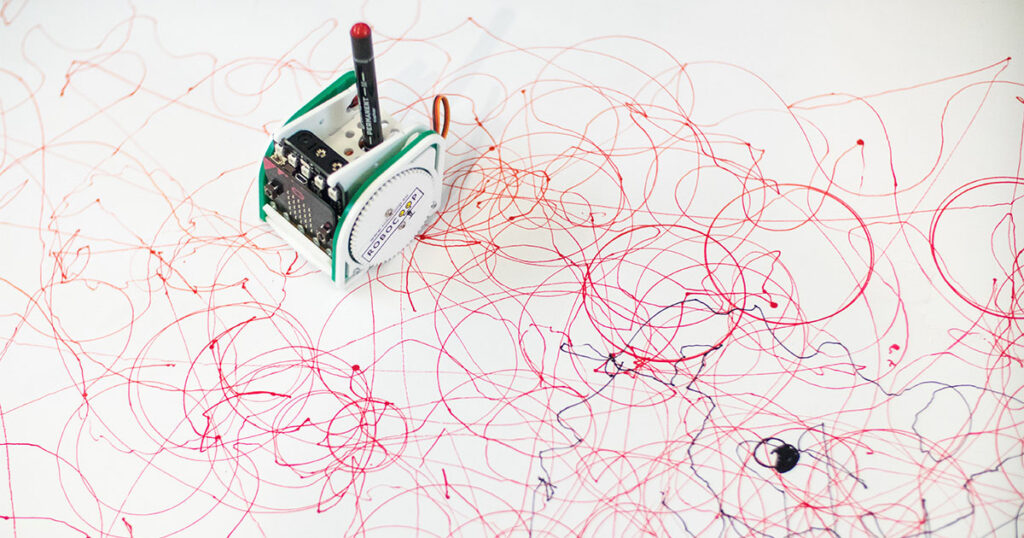

Hajdu proves the point that machines are and have long been instruments that are used by humans to make new art and music, and that’s a good thing. But he’s trying to articulate something even bigger, a concept hinted at by the architect Philip Johnson in 1934: “The craft spirit does not fit an age geared to machine technique.” Hajdu calls this statement “practically a manifesto for a new way of thinking about machines: as tools that were not merely conduits for human agency but tools whose use could carry distinctive characteristics that suggest something approaching a kind of agency of their own.”

The development of machine learning, however, goes far beyond this. Cutting-edge technologies such as AICAN and ChatGPT generate their own content. Bye-bye, mankind? It’s easy to dismiss AI creations as not up to human standards of technique, innovation, emotion, and thought. But Hajdu, quoting computational creativity scholar Simon Colton, raises a more interesting question: What if the point is not how AI art expresses the human condition, but how it speaks to “the machine condition”?

The case against AI goes back at least as far as Descartes’s statement that thinking is what makes us human. By focusing primarily on European and American art, Hajdu limits the scope of his book to Western ideas. That in itself seems a little old-school. He is so authoritative in his knowledge and references that I was surprised to find that Hajdu failed to cite the work of science historian Donna J. Haraway. Her writings on the relationships between humans, animals, and technology, beginning with her 1985 essay “A Cyborg Manifesto,” address many of the existential questions that drive Hajdu’s episodic history of artistic production and machines. She writes that science and technology have already erased the line between man and machine, and that feminists and animal-rights activists place humans as equivalent, not superior, to other species. “A cyborg world might be about lived social and bodily realities in which people are not afraid of their joint kinship with animals and machines, not afraid of permanently partial identities and contradictory standpoints,” Haraway wrote. Thinking that art is the sole province of human endeavor is the stuff of old white men. Have you ever seen an orb weaver’s sculptural masterpiece, or listened to a mockingbird’s vast repertoire? Hajdu ultimately reaches a line of thinking similar to Haraway’s but without crediting her. In that, he shows that humans are as fallible as the technologies they create.