The New Leviathans: Thoughts after Liberalism by John Gray; Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 192 pp., $27

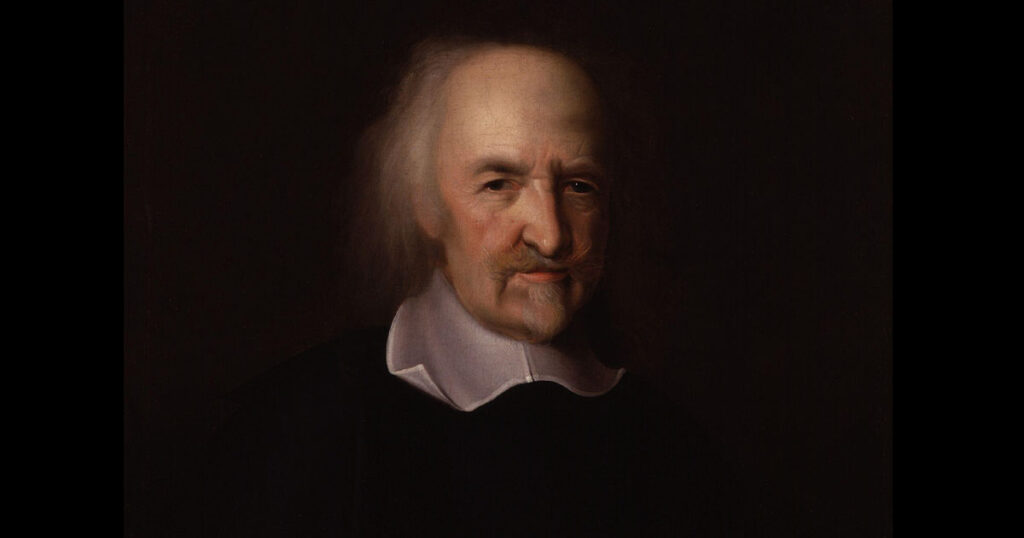

Was Thomas Hobbes being ironic when he titled his 1651 masterpiece Leviathan? The name alludes to the mysterious sea monster mentioned a half-dozen times in the Bible: something unfathomably massive, powerful, and fearsome. In his book, Hobbes was referring to something similarly gargantuan and dangerous, yet man-made: the sovereign nation-state, which alone, he asserted, possessed sufficient power to pacify the innately violent human race. Was Hobbes, then, critiquing our hubris, our tendency to worship ourselves and our own creations? That’s likely John Gray’s take, for at the end of his new book, The New Leviathans, he writes that “the real Leviathan is the human animal.”

The author of more than 20 books, many profound-to-the-point-of-life-changing, Gray is a British philosopher with an unparalleled ability to pull the rug out from whatever you believe. Best known for Straw Dogs, in which he contended that progress is a myth, in that whatever is achieved can be lost, he eloquently smashes the concepts with which we understand the world. In his new book, for instance, he declares: “History is like Humanity, an iridescent apparition. All that exists are mortal humans with their jarring and fading anecdotes.”

I think of Gray as a philosophical descendent of Nietzsche and Schopenhauer, yet since retiring from the academy in 2008, he no longer considers himself a philosopher but a writer, albeit of short books that keep getting shorter. The New Leviathans is slim but feels immense, an intricate polemic that rewards slow, thoughtful reading.

Hobbes was an archetypical realist, but Gray nevertheless sees him as “a liberal—the only one, perhaps, still worth reading.” Liberalism itself consists of four ideas: individualism, egalitarianism, universalism, and meliorism. Hobbes’s Leviathan has a single purpose: to secure its subjects against one another and external enemies. That was all well and good in the 17th century, Gray writes, but contemporary nations have become “engineers of souls.” Whether in dictatorships or democracies, he observes, “there is an unrelenting struggle for the control of thought and language.”

Gray presents a bleak perspective, one in which societies often unwittingly cause their own demise. In doing so, he delves into the rabbit-holes of history, illuminating the provocative ideas of obscure thinkers—like Konstantin Leontiev and Vasily Rozanov, anti-liberal Tsarist Russian writers of the 19th century who, Gray suggests, anticipated how liberals would eventually turn on the very societies that nurtured them, like a “creature eating its own tail.” Some may lament this turn of events for the tragedy that it is, yet Gray views its unfolding as “an absurdist comedy.” But as the Russian writer and humorist Nadezhda Teffi wrote during the Bolshevik revolution: “Life inside a joke is more tragic than funny.”

One might wonder why Gray focuses so much on Russia, its unfathomably violent civil war, and Soviet experiment. It’s not merely to relay chilling bits of history, but to show that the “same mixture of self-deception and adamant certainty” is driving 21st-century “hyper-liberals.” As usual, Gray’s perspective challenges both the right and the left, but it is the left that receives his most scathing critiques. For Gray, the ideology of the far left is neither Marxist nor a version of postmodern theory, for its practitioners lack the “rigour, breadth and depth of thought” of Karl Marx, to say nothing of “Jacques Derrida’s playful subtlety or Michel Foucault’s mordant wit.” Going further, Gray argues that, like the machine-smashing Luddites, today’s “woke” progressives are no longer progressive in the traditional sense, having creating not only a culture of illiberal intolerance but also a self-sustaining industry out of the enterprise. As Gray devastatingly states, “Woke is a career as much as a cult.” As a consequence, Gray sees “inquisitions staged on Western campuses”—where free speech is inhibited and diverse viewpoints are discouraged—as “a mark of advancing barbarism.”

What do all of Gray’s critiques, quotations, aphorisms, and anecdotes add up to? Perhaps he simply wants progressives to answer for themselves the question that Isaac Babel raised while fighting with the Red Army: “We are the vanguard, but of what?” The Bolsheviks believed they were creating a workers’ paradise, but they brought hell to Earth. Similarly, from the clear-eyed, cold-hearted perspective of history, Gray sees beneath our liberal experiment gone awry an unconscious death wish at work. Ultimately, the Leviathan that was supposed to provide us safety and liberty is denigrating toward dangerous, illiberal despotism. And unfortunately, we can’t prescribe a return to a purer liberalism as the solution to our problem, for that would be like telling a dying old man that the remedy to his disease is to become young again. It’s just too late for that.