Adventures in the Anthropocene: A Journey to the Heart of the Planet We Made, by Gaia Vince, Milkweed Editions, 448 pp., $30

Gaia Vince is hiking through Pokhara, a Nepalese lake town located about 125 miles west of Kathmandu. Nepal’s prime minister has vowed to transform the impoverished Himalayan country into the “Switzerland of Asia,” with Pokhara as the picturesque vanguard of that ambitious plan. Vince notes the lively cafés and shops dotting the lakeside, colorfully dressed crowds heading toward a Buddhist temple, fish leaping from the water, birds wheeling overhead …

But on closer inspection, the scene looks decidedly less Julie Andrews. Vince sees a “fetid slick of vibrant green run-off”—a mix of raw sewage and oily pollutants—issuing from the cafés and businesses directly into the lake. The town’s seemingly “quaint country homes” are really “dilapidated mud-floored shacks.” Children scavenge through piles of trash. And it is mid-December in the Himalayas. There should be ice on the lake, snow blanketing the surrounding mountain slopes. Instead, only the tallest peaks are white, and Vince has to stop repeatedly to peel off yet another layer of clothing. As she watches a boy squat down and defecate by the lake, Vince can’t help thinking, “We’re a long way from Switzerland here.”

Or are we? And if so, for how long? Vince’s impressive book, encyclopedic in its scope and relentless in its gumshoe derring-do, covers many site-specific examples of how humans have profoundly altered their environment. Its overarching theme? Global climate change is real, dear reader. Groan or yawn or roll your eyes all you want, but it’s here, it’s severe, and it’s about to get catastrophically worse. Sure, Switzerland may not be as immediately vulnerable to the effects of a warming climate and melting ice sheets as, say, the Maldives, an island state that Vince also visits. But how many droughts, floods, hurricanes, blizzards, heat waves, insect infestations, disease outbreaks, and other carbon-driven whacks can even the richest nations withstand before the fastidious grid of modernity begins to break down, garbage is left to molder in the street, power is out more often than on, supermarket shelves go unstocked for days or weeks at a time, crime rates climb, and the local alpine lake pinch-hits as laundromat and public loo? I wish I were exaggerating, but I’ve talked to enough scientists who are riven with anguish, who feel like background characters in a comedy as they jump up and down and wave their arms and try desperately to keep our clueless heroes in the foreground from doing something colossally stupid.

Vince, formerly an editor for the journal Nature, is well aware that global warming and related ecocrises are real. She has reviewed thousands of studies and spoken with countless scientists—about deforestation, ocean acidification, islands of plastic garbage afloat in the Pacific, the loss of arable farmland, the damming of rivers, vanishing migratory butterflies, the mind-boggling quantities of concrete that are poured every moment of every day, among other worrying trends. Yet she also heard plenty of positive news, evidence of “our triumphs, the genius of humans.” She learned how scientists were devising novel ways to cure today’s plagues and forestall tomorrow’s, breed hardier and more nutritious plants, grow meat and spare body parts in Petri dishes, design amazing new materials—invisibility cloak, anyone?—and robots to do our every bidding, including cleaning up the muck left by the geniuses who came before.

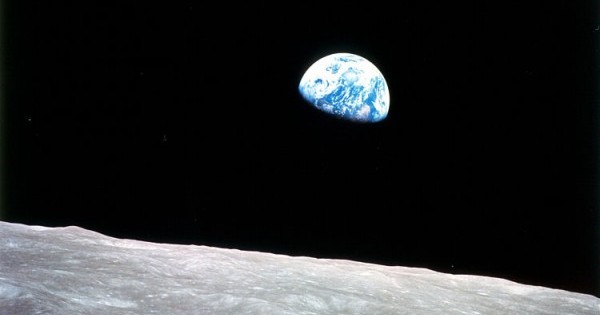

“No part of this planet is untouched by human influence,” Vince writes. “We have transcended natural cycles, altered the physical, chemical and biological processes of the planet.” Humans aren’t just another species anymore: we’re a whole new geological epoch. We’ve swept away the Holocene—the slice of geochronology that began with the end of the ice age some 12,000 years ago—and ushered in what Nobel chemist Paul Crutzen designated the “Anthropocene,” a time when human beings are the dominant force on Earth. We’re leaving so many fingerprints on the biosphere that future paleontologists will be able to read the onset of the Anthropocene as readily as today’s scientists detect the end of the Cretaceous period in a worldwide layer of iridium dust, the remnants of the meteor impact that killed off the dinosaurs and 75 percent of other living species 65 million years ago.

Vince wanted to see these changes for herself and talk with people in places most affected by them, so she left her London job and set off on a two-year international odyssey. And wow, did she take her mission seriously! There she goes, hiking up arduous mountain passages as vultures coast on thermals beside her, hunting with Hadzabe bushmen in Tanzania and watching as one hunter dispatches his avian prey by popping the bird’s head in his mouth to sever its spine; gliding down the Mekong River in Laos aboard a flat-bottomed wood boat, snacking on “citrussy” red ants and then riding a rented scooter 50 miles into the jungle; diving with biologists off the coast of Maldives in search of whale sharks, the world’s biggest fish; tracking jaguars in the Pantanal of South America and Bengal tigers in the lowlands of Nepal; and crawling deep into one of Bolivia’s oldest silver mines “through tunnels tight enough to panic in,” choking on air that is infernally hot and thick with caustic dust, and incredulous that miners work in such conditions.

Her book is an emporium of fascinating information, much of which I should have known but didn’t. For example: not only do humans now control nearly three-quarters of the world’s supply of fresh water, but by capturing and redistributing its weight around the world—through dams, reservoirs, pipelines, irrigation and the like—we’ve also slowed the globe’s spin by a fraction of a second. Humans and their domesticated animals now account for more than 95 percent of the terrestrial vertebrate biomass, up from just 0.1 percent when the Holocene began. We have truly worldly gullets: roughly 40 percent of the world’s non-ice land surface is now used to grow crops. But we’re losing about 38,000 square miles of arable land each year, partly to our ever-swelling cities. “And because cities have usually grown from settlements on the most fertile land,” Vince writes, “vast urban centers are now squatting on some of our best soils.” The urban garden movement makes more sense than we realize.

Vince meets with an array of everyday heroes and can-do inventors who are acting locally to confront global miseries. Melting mountain glaciers? Chewang Norphel, an engineer in Nepal, builds artificial glaciers cheaply and ingeniously, by diverting waste water to pools under trees, where the shade keeps the water frozen through winter, a precious reservoir to be used in spring planting. Islands vanishing as sea levels rise and plastic rubbish mounting out of control? Gerald McDougall, a Creole-speaking fisherman, has fashioned an island he calls Westpoint a couple of miles off the coast of Belize, painstakingly layering mud and sand with plastic, sawdust, and burned tin cans, and planting papaya and coconut trees to lash everything together with roots. In Lima, Peru, the largest desert city after Cairo, Javier Torres Luna and his neighbors are tapping new sources of water by harvesting fog, setting up large nets to capture airborne water droplets that then coalesce into streams. Ingenious as they are, the projects Vince describes often seem like so much duct tape on the windows in the advance of Hurricane Sandy. Still, evidence of human creativity always helps blunt the despair, just as the European Space Agency’s triumphant comet rendezvous helped salve the sting of ISIS and Ebola.

Paradoxically, we may find our salvation in increasing urbanization. More than half of all people now live in cities, and the numbers keep climbing, perhaps because cities, Vince writes, are where “humans feel most at home.” Cities can present terrible problems of their own, including slums and epidemics and bad air days, yet they are also impressively efficient. For every doubling in their population density, resource use and carbon emissions plunge by 15 percent. People work better in crowds. The citizens of nations with a lot of cities earn about five times more than their counterparts in countries that remain rural, and the economic output of a city of 10 million inhabitants will be some 20 percent higher than the combined output of two cities of five million people. As Vince writes, “The urban revolution of the Anthropocene could prove the solution … allowing humans to inhabit the planet in vast numbers but in the most sustainable way.” Or cities could prove our demise, “the dystopian megacity so often portrayed in science fiction.” Vince sides with the optimists here and ends her rigorously fact-based and footnoted expedition on a fictional reverie. She imagines her infant son in the year 2100 as an 87-year-old man living in a radically transformed London. She gives him what all parents want for their children: a future, a purpose, and hope.