The Dinner Party

Certain things shouldn’t be brought up at the dinner table, but in our fraught time, that’s nearly impossible

If you ignore the whine and hiss of overworked radiators, the dinner party is running smooth as tapioca pearls. I give myself a mental high five.

Go me!

Go Steven too, of course. My husband did most of the cooking, but that’s only fair since he’s a chef. Tonight, we’re entertaining Steven’s father, Jim, along with Clare, Jim’s fourth wife. And Celia, our sweet daughter home from college for the evening.

Over our laden table, everyone clinks glasses in a toast.

“To family, and difficult times finally easing up,” I shout over the radiators. There. Nice and innocuous.

You have to be careful at dinner parties. Jim and Clare are staunchly Fox News, while Steven and I (and our daughter Celia, because the apple didn’t fall far from the tree) lean strongly toward NPR.

Jim is also a shit-stirrer of the first degree, and though Steven and I vowed not to let him goad us into political arguments, Celia made no such promise.

I wanted my daughter desperately: I craved Celia with all my squishy heart, with every droplet of soul, should such a thing exist. Bringing her into the world was the wisest choice I’ve ever made. If I believed such things, I’d say Celia followed me from previous lives. I wanted her so vehemently that, when Steven and I discovered his wonky sperm, we hit up a fertility clinic and I took drugs to regulate my egg production, even though they left me starving as a black hole, jumpy as a treefrog.

Meanwhile, Steven visited a back room at the clinic with a racy magazine tucked under his arm. Upon making a deposit, his three or so working sperm were polished in a petri dish and reinserted into me via a turkey baster–like device while I stretched my legs in the stirrups, shut my eyes tight and imagined Keanu Reeves (sorry, Steven).

I wanted Celia with such ferocity that I quit the antidepressants that maintained my comfortable brain balance and kept me solid in my skin. And when I read the two pink lines on the pregnancy test, I shrieked for joy. All through Celia’s incubation, I cradled my expanding belly like a sleepy puppy and begged her, Just hold on, baby. Stay put for a while more, till you’re fully cooked and ready to come out.

Still, that’s not the entire story. Between the cradling and begging, I cried like the world was burning. Pretty much the whole way through my one-and-done pregnancy. I blame part of it on quitting the antidepressants. But—and you can call me unnatural now—I also disliked the whole experience of being pregnant, the claustrophobia induced by the forced sharing of my body with another being, the suffocating realization of Oh shit. What have I done?

At the dinner party, after three sorts of cheese and swanky crackers, after grilled eggplant and corn on the cob and salmon, but before Clare’s home-baked blueberry pie and coffee, Jim refills his glass of Merlot and tops off Clare’s for good measure. He offers the bottle to me.

“I don’t drink red,” I remind him. “Headaches.”

Twenty-year-old Celia holds out her glass and Jim looks to Steven before pouring.

“It’s fine,” I say.

Steven raises his Clausthaler NA in one final toast of the evening. “Here’s to being together after so long apart.”

Everyone lifts glasses—I’ve recently shifted from prosecco to water. We drink. An uncomfortable silence follows, all of us having exhausted our “safe” topics: recent Netflix binges, Celia’s relief that her senior year in college was in person instead of online, some discussion of Jim’s step-granddaughter who, according to Clare, has put on weight and looks downright hefty, this past month’s changeable temperatures, the late spring cold snap that sent our radiators into overdrive.

Then Jim gets that look on his face, like he’s up to no good.

“Sooo …” he starts, dragging out the word to build suspense.

Clare takes a delicate sip of wine. “Some people …” she begins, then trails off.

Jim gives us a little half smile. “So … About those cases up before the Supreme Court. The rulings are going to be announced any time now.”

I gulp my water, wishing I hadn’t put aside the prosecco quite so hastily.

At the very least, the myth of perfect femininity is a Victorian holdover and goes as follows: women are innate mothers. Our bodies are crafted for it and our feeble brains have no choice but to hop aboard the mommy train. Our uteruses might not wander willy-nilly around our torsos à la the ancient Greeks and Edward Jordan, but we’re nonetheless intrinsically and unequivocally shaped by the reproductive organs we happen to house. As such, we share an instinctive bond with our fetuses that overshadows higher cognition. They grow in us, are built from our blood and flesh. To not form an immediate love connection with the cells expanding in our bellies makes us unnatural women. See, it all comes down to nature.

As stated above, it’s a myth, long debunked.

You’d think so anyway. Yet those fairy-tale ideas pop up at the oddest times. Like at the Social Security office when I was so pregnant, I couldn’t catch a glimpse of my own feet, much less scratch the itchy one. The man beside me, big and bald with a spiffy goatee, and I had been similarly failing to make ourselves comfortable in the metal chairs when he pointed at his protruding belly, then at mine. “We sorta match, wouldn’t you say? But at least you glow.”

“I don’t glow,” I told him. “Trust me.”

“Naw, you do. Cause you’re so happy about the baby and everything.”

I’d said nothing, made no gesture to indicate I was happy. I wasn’t in the least. I mostly managed to limit my weeping to the privacy of home, traffic stops, or the stalls of public restrooms, but the despair that cinched me through my pregnancy was nearly constant, so I felt sure my girl would emerge in a torrent of saltwater.

And that “glow”—the excess blood flowing to my vessels and flushing my skin—was also raising my blood pressure and swelling my ankles.

Then there was that time in the grocery store when Celia was young, still strapped up front in the shopping cart. She and I had been discussing the benefits (me) and drawbacks (Celia) of avocados when a well coifed, elderly lady interrupted.

“Hello,” she said to Celia who declined to respond. She tried me next. “You have such a beautiful connection with your daughter.” I thanked her, and she added, “If you don’t mind me saying so, I can tell you were older when you had her.”

Uh, thanks.

“I guess your life is finally complete now,” she said.

“Huh?”

“Well, I’m sure you’ve done a lot of interesting things with your time. But there’s no more important work for a woman than being a mother.”

Though Steven attempts to divert Jim from the path down which he’s determined to lead the dinner conversation, my father-in-law is officially off his leash, raising various world affairs as though he has to stuff them in before the evening ends: the war in Ukraine, the coronavirus and its new BA.2 strain, the Amazon on the brink (Jim doesn’t believe it), a recent attack of the Islamic State in Israel that led to two deaths, rising inflation, gas prices.

We nod dutifully after his recitation of each disaster.

“And how do you think President Biden is managing these crises, hmm?” he asks.

Clare huffs.

“Who wants decaf?” I ask before she can elaborate. After taking orders, I head to the kitchen, hoping Celia will follow so we can roll our eyes at each other, but she stays put. I only barely hear what happens next. Something about the Taliban’s resurgence in Afghanistan, the dwindling rights of women there.

I return to Steven and Celia’s scrunched faces, along with Jim’s smile out in full force.

“What’s going on?”

Celia scowls. “I think it’s hypocritical to say a group of people you don’t like is harming women, but we used drones in Afghanistan. That hurts women too. It’s like you’re saying you’re for women’s rights while still being pro-life.”

“We’re pro-life,” says Clare. She looks over at Jim and catches his hand in hers. “And they’re just helpless babies. Someone needs to defend them.”

I get it. Babies, I mean. I chose to get pregnant. I’d fight for my daughter with all my teeth and claws. I’m also privileged to have a life partner, along with good health insurance, a safe home, etc. I think of the current suffering in Ukraine, and across the world, and count my blessings.

Yet pregnancy was nearly unbearable for me. And at the end of it, I got double whammied with postpartum depression on top of my everyday depression. I’d also been gifted a daughter with severe reflux and sensory issues that made the brightness and loudness of the world painful to her—which she let me know, vociferously.

After the bliss of Celia’s arrival into the world, my days turned gray. She and I were wretched. To make matters worse, I didn’t know this new, squirming person, this wailing, unpleasable human. It was a far cry from the myth of perfect, magical femininity.

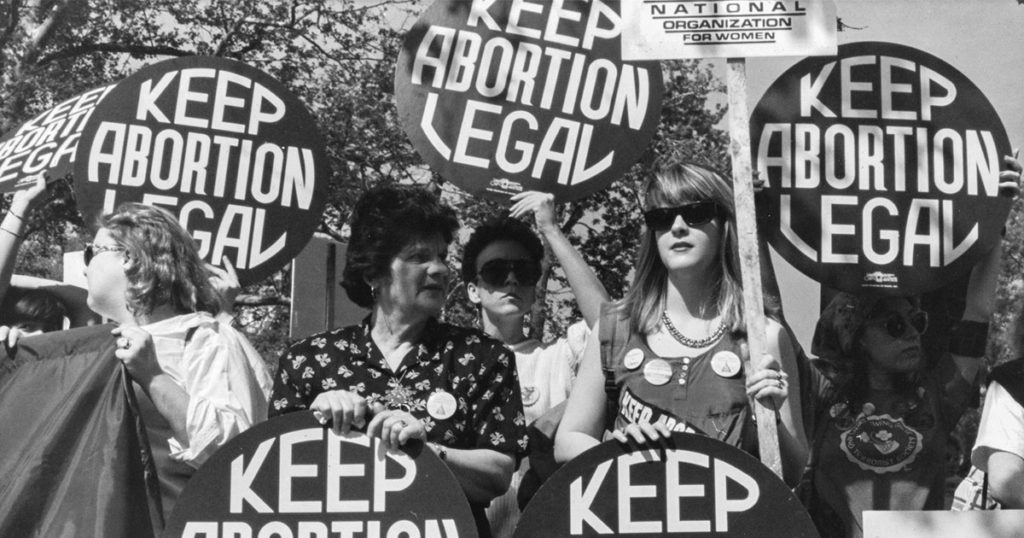

Abortion at a dinner party—there’s no greater hot-button issue, no bigger agitator, no other topic that carries such bludgeoning weight. And though Celia might not know it yet, there’s simply no way to win this train wreck of an argument, or even salvage the conversation.

Not that she tries. “I don’t get it,” Celia says in response to Clare. “Being pro-life is like telling someone they’re legally obligated to give blood transfusions to save a dying stranger. It’s saying a woman has to give up control over her own body in order to help somebody else, even if she doesn’t want to.”

“Well,” says Clare. “She should’ve considered that before getting pregnant.”

I’m officially sucked in. “Now wait a minute—”

Steven shakes his head.

Jim’s voice rises in decibels, ringing clear above the still straining radiators. “Transfusions and babies are not the same thing at all.”

“No. You’re right,” says Celia. “Because no one would argue a person, especially a man, has to give a transfusion if he doesn’t want to, even if he has a rare blood type and he’s the only one who can save another person’s life.”

I look at the blank expressions on Jim and Clare’s faces. “Think of it like being forced to give a kidney to a stranger,” I try. “No one would say someone is obliged to do that.”

“But a baby isn’t a stranger,” says Jim.

“A fetus,” says Celia.

“Of course, it is,” I say. Everyone looks at me. “A fetus is a temporary houseguest. One you’ve never met in your life.” Steven facepalms.

“But how is a baby the same as a kidney?” asks Clare.

Celia sets her hands on the table. “Because if pro-lifers have their way, women will be forced to provide their bodies to save someone else’s life. And not even a full person. But you’re right. Transfusion isn’t like pregnancy because pregnancy is dangerous. Women still die from it, they become incontinent, they tear during birth, their bodies are changed forever.” Celia’s near tears now.

Jim, Clare, and Steven stare hard at Celia. But even Steven doesn’t know Celia as well as I do, how deeply, passionately, she cares about this issue.

Jim opens his mouth, closes it, then opens it again. “Is there a reason this is so personal to you?” he asks my daughter.

“No,” Celia snaps. “I’ve never gotten an abortion—”

“Well then,” says Jim. “I still fail to see how your argument relates to babies—”

“Fetuses—” I say.

“It’s obvious—” begins Celia when Jim cuts her off.

“Don’t interrupt and roll your eyes at me, young lady.”

Celia shuts up. Jim then steers the conversation to late-term abortion, to near-term babies being delivered in their teeny-beeny cuteness, only to be shredded by abortion providers wielding scalpels of death.

Never mind Clare’s homemade pie; the evening is well and truly kaput.

I know the myth of perfect femininity denies it, but lots of women don’t want to be mothers, either during certain periods of their lives, or ever. Their reasons are endless and personal. These women are not outliers of some fairytale biological inevitability. Call the myth what it is—a lie.

The United States is currently divided for many reasons, access to abortion being one of the biggest. In some states, invariably the blue ones, women are still allowed to make their own choices as relates to carrying a fetus to term. If the decision is made prior to a fetus’s viability, it’s the business of the woman and that’s that.

In many red states, however, that situation has changed dramatically over the past several months. Because Texas passed SB8, and the Supreme Court gave its thumbs-up, abortion is all but outlawed there. Further, with the Supreme Court set to rule in June on a Mississippi law outlawing abortion after 15 weeks, a supposedly secret copy of the decision has already been leaked to the press, and now everyone knows that Roe v. Wade will likely be overturned. How many more states will then follow Mississippi’s example? How many will ban abortion outright?

As for Steven, Celia, and me, we live in Michigan, a blue state that upholds women’s right to choose. For now. Because a rabidly gerrymandered Republican legislature is dogging Governor Gretchen Whitmer’s heels every step of the way. God forbid that Celia needs an abortion someday, when she might not legally be allowed to obtain one.

I’ll do what I have to. Drive her to Canada. Fly farther if necessary. I’ve got resources and friends who love us. Who understand the dead seriousness of this game our nation is playing with our lives.

Not everyone is so lucky.

I was sure Steven got it. After Celia made her argument and he met my eyes across the dinner table, he was onboard with our thinking. He’s pro-choice after all, a proud feminist. But you never know when myths will insinuate their prickly tentacles.

By this point, Jim and Clare have long vamoosed. The radiators have been pumping humidity into the air, and my once-straightened hair frizzes like a wild nimbus around my head. Celia has wandered upstairs to text her boyfriend.

Steven rolls his eyes. “That was a disaster.”

“Oh yeah.”

“You know there’s no changing people’s minds when it comes to abortion.”

“Some ideas stay stuck to the bitter end,” I say. “But our daughter made a good case, huh?”

“How do you mean?” asks Steven. “Her argument was baffling. How can transfusions be the same as babies?”

Whoa. I wasn’t expecting that.

He’s not done yet. “A medical procedure between strangers is a transaction; no one should be forced to participate if they don’t want to. But it’s natural for women to share space with their babies.”

“Natural,” I say. Steven must hear something in my voice. He puts down the sponge he’s using to wipe the counter and nods.

“What’s natural is that fetuses are parasites sucking nutrients from their hosts. In the beginning, the fetus is just a cluster of cells, and even after the cells grow fingers and kidneys, their sole purpose is survival, never mind how it messes with a woman’s hormones and brain and body with no consideration of her wants or needs.”

“Well—” begins Steven.

“It might be natural,” I finish, “but that doesn’t mean it’s different than any other transaction.”

Steven raises his hands in surrender, but I’m still frustrated. I want to explain how mothering didn’t come naturally for me. I couldn’t even change a diaper in the beginning; the nurses taught Steven in the hospital, but figured that as the woman, I surely knew already. I couldn’t innately relate to the tiny, flailing human for whom I had total responsibility. I stopped sleeping; my milk didn’t come in. I cried. A lot. After months of this, Steven begged me to restart my antidepressants. The doctors eventually added more meds to make me sleep. Finally.

Here’s the truth I’ve never admitted to anyone: had some higher being rung my doorbell back then, during those first, terrible months, and offered me the opportunity to go back in time and make a different choice, I might have considered it.

That was then. Nowadays, Celia is my favorite person. I’d fling myself into a volcano if it spared her the same fate. But our relationship didn’t come in an easy flash. Like all steel-hard bonds, ours took time. Maybe not a lot in the scheme of things, but we had to learn about each other. I had to discover the person Celia was becoming after the early days of vomiting and screaming, followed by the months of guessing what she required from me.

I’m the only parent I know who celebrated her child’s first No! Thankfully, Celia’s came early. Finally! She can communicate a clear opinion about her needs.

And because Celia turned out to be a careful person, I had another partner in keeping her alive.

Because the world is a terrifying place, chockful of pandemics, school shootings, climate crises, unprovoked wars, difficult relatives, bad hair days, stress and fear and frustration. Strangers who want to take away our self-determination. Boiling volcanos around every corner.

On a recent Sunday, I visited Celia in Ann Arbor, where she’s recently graduated from the University of Michigan.

At Celia’s ramshackle house, I hand off the dried seaweed and raspberries I brought in my continuing plot to keep her alive. Afterward, we head to Panera for an early dinner. Upon collecting our laden trays, we settle into the outdoor seating area and catch up on what we missed since texting earlier that day.

I dunk my baguette into tomato soup and make a confession: “I told your dad not to come today. Said I needed alone time with my girl.”

Celia smiles her perfect smile. “I’ll see him next week.”

We talk about her classes and the lab position she’s taken. About Ukraine. About the likely end of Roe v. Wade and the painful repercussions for women across this nation. About the recent dinner party with her grandfather and this essay I’m writing.

“How’s it going?” she asks.

“I’m stuck at the end. What do you remember about that night?”

She tells her version of events. “Mostly I felt frustrated. Because I thought transfusion was a good parallel to forcing women to carry fetuses when they don’t want to, but no one got it.”

“I did.”

“Well, yeah. You’re the one who explained things to me in the first place. About how the world works for women.”

I cringe. In my conversations with Celia as she grew up, should I have laid off the real-life difficulties many women face in favor of the magical joys of mythical femininity?

“Er, sorry,” I say.

“No way. I’m glad I know everything I do.”

She means it. Celia can’t bear pretty lies, even as they ease our way through life’s excruciating moments. I know. I tried often enough during her childhood to soften this or that reality: bigotry in its endless permutations, the brutal people who harm children, the repercussions of war, how death arrives in all its randomness and we’ll never know with certainty what comes after.

But Celia wouldn’t have my saccharine fumbling. She picked at me, at her father and her teachers like the woodpecker at our apple tree until the darkness of what she learned left her trembling. And still, she had to know. How else to recognize light? How else to learn compassion?

“You understand, right?” I ask her. “That most people won’t budge when it comes to abortion. How it’s probably not worth the argument.”

“I get it.” She shakes her head. “Grampa Jim is just frustrating sometimes, even if he did call to chat and apologize.”

“He did?” Go figure.

I take a second to recalibrate my opinion of my father-in-law. None of us are one dimensional after all, something that’s easy to forget in the heat of disagreements.

“Yep. He’s all right, I guess.” Celia slurps the last of her soup, pops the final bite of grilled cheese into her mouth, then starts on her chocolate chunk cookie, breaking off little pieces to savor it longer. “He’s still a man, though. You know, I read somewhere that men invented patriarchal religions because they can’t create life on their own. So they came up with a male god who can.”

“Makes as much sense as anything.” I look at my daughter across the table, at her mermaid hair, her narrowed eyes as she considers some vital truth. “It’s challenging work being a woman, huh?” I ask her.

“Pa-lease,” Celia rolls her eyes. “Women rule. God just wishes he were us.”