The Doctor’s Discontents

A harshly critical new biography of the father of psychotherapy

Freud: The Making of an Illusion by Frederick Crews; Metropolitan, 768 pp., $40

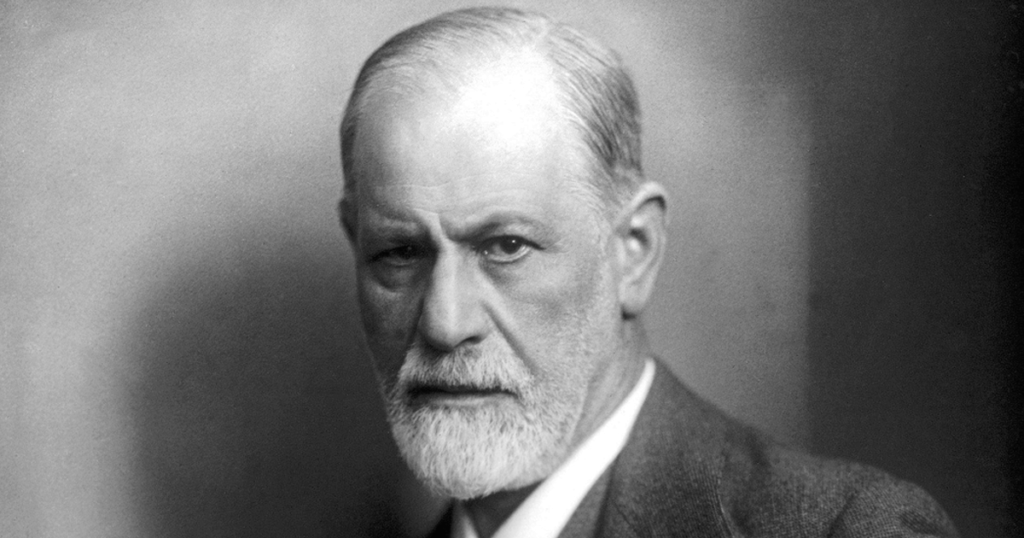

The Freud Wars may be over, but Frederick Crews is still shooting. Freud’s thoughts about human nature are not regarded as scientific, despite his aspirations to being a scientist. And many of his views on women (for instance that they suffer from a castration complex) are now roundly reviled. Few people believe that classical psychotherapy—five times a week, patient on the couch, analyst given to prolonged silences—is efficient or effective. Drugs like Prozac, it’s thought, have done more to help patients than psychoanalytically oriented therapists ever could. Insurance companies are increasingly hesitant to fund Freudian therapy. Freud himself is certainly no longer the colossus that W. H. Auden hailed in the great elegy he wrote in 1939, the year of Freud’s death: “A whole climate of opinion / Under whom we conduct our differing lives.”

My students at the University of Virginia, smart and well informed as they are, know almost nothing about Freud, except (usually) that he experimented with cocaine. To them, Freud is a relic of another time. A few therapists and professors continue to write about Freud and conduct classes on his work—I am one of the latter—but their numbers are declining. One of the causes—one of many—for the near-disappearance of Freud from the culture at large is the work of Crews. A professor emeritus of English at the University of California at Berkeley, he has written a series of essays about Freud, many of them published in The New York Review of Books. In them, he has attacked Freud’s ideas (not scientifically verifiable at all, he says) and his character (he takes Freud to be deceptive, selfish, manipulative, and more). Agree or not with the spirit and the conclusions of those essays (and I generally don’t), one has to admit that they are informed with wit, brio, and learning.

Crews’s latest contribution in this area is a massive biography that covers Freud’s life in excruciating detail up until about 1900, the year he published The Interpretation of Dreams. Missing are the wit and energy to be found in Crews’s earlier work. Instead, he offers a relentless diatribe against Freud, who seems to merit nothing but scorn. The book is comprehensive and accurate, but its unremitting contempt for its subject makes for an exhausting, dispiriting read. Never have I read a biography of a cultural figure that is so programmatically hostile, so lacking in nuance, subtlety, or indeed, simple humanity. Even the harshest political biographies will occasionally give their subject the benefit of the doubt. Hitler’s biographers, for example, generally pause to acknowledge that the future Führer was kind to his mother. But Freud apparently deserves no quarter.

To Crews, Freud is a villain whose work is rife with bad ideas, except for those he adapted from others. We hear in detail about Freud’s episode with cocaine—which, it is true, may have cost a dear friend his life. We learn that Freud betrayed his teachers and associates, that he did not tell the truth about his case histories, that psychoanalysis virtually never worked for anyone. Page after page, the indictment rolls on. For all of the book’s scholarly merits, the strength of its denunciation makes it virtually impossible to credit. We hate poetry that has a palpable design on us, said Keats. We do not care for such prose either.

There is much to say about Freud’s fall from cultural authority, but one point bears mentioning. My students come to school with almost no vocabulary for understanding their inner lives. They know nothing about Freud’s mapping of the psyche: his account of the ego and the id, and after 1914, of the superego. They have no idea what triggers dreams or how they might be interpreted. They know little about theories of the unconscious. Their sense of the psychodynamics of family life is usually all too simple. Freud’s ideas about authority and how it works in the public sphere are news to them. The transference—Freud’s theory about how we carry past prototypes into the present—is not available. When they get into psychological trouble—as college students often do—they have no illuminating terms for self-understanding at their disposal.

Freud’s terms are not perfect, far from it. But for those who need to develop their powers of introspection—and who doesn’t?—his concepts are a superior starting point. Freud’s exile from the culture has effectively left a generation without access to what probably remains the best takeoff point for understanding the inner life. The critique that Crews and others have put forward about Freud’s aspiration to being seen as a scientist doing scientific work seems to me entirely justified. Even so, that critique should have opened the way to our seeing Freud for what he is: a moral essayist far closer to Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, and Emerson than to any authentic scientist.

Freud’s banishment has had another effect, too: the prevailing terms of discourse and debate are now political. To be sure, the political idiom has its place, but when people lack a vocabulary to describe their inner lives, culture becomes thin, impoverished. Many of us now seem to feel that if we could only usher in the right political dispensation, we could be truly happy. Get him out of the White House! Get her into the Senate! Pass some new laws against bigotry! Then all will be well in the world, and one could begin to be happy. It’s pretty to think so.

In his elegy, Auden said that Freud wanted to make us more tolerant of our own inner lives, more relaxed and more accepting. Auden writes that “He would have us remember most of all / To be enthusiastic over the night … / Because it needs our love: for with sad eyes / Its delectable creatures look up and beg / Us dumbly to ask them to follow; / They are exiles who long for the future / That lies in our power.” From our dreams, Freud and Auden thought, we can learn the most necessary and simple truth, the truth of what it is we genuinely desire.

Peter Gay, Freud’s great biographer, said that Freud taught us that there is more to understand and less to judge than we had realized. That’s still something worth knowing.