The FBI, My Husband, and Me

What I know now about Ted, whose photographs documented the 1960s, and about J. Edgar Hoover’s attempts to label him a Soviet spy

Listen to a narrated version of this essay:

After Ted died in 2003, and I was finally at home and alone following the daze of formalities, I found myself methodically going through all of the pockets in his suits and jackets and coats. Borderline delusional, I know. But I thought he might have left me a note. Something he had forgotten to tell me, even though I’d been with him all those last hours and weeks and months, and the 36 years before that.

There was no note. So I crawled into a storage space under the basement stairs to pull out a box of old photos and some faded documents we inherited from his mother. Along with a cache of studio portraits of a very young Ted (“He vas my doll,” his mother once told me in her thick Russian accent), I found an envelope filled with snapshots taken during his first few months at the University of California. Ted in his room at the International House on the Berkeley campus, Ted piled in a jeep with a covey of new friends. He had sent the photos to his parents in China, with messages written in Russian on the back. In one dated May 1947, just two months after Ted’s arrival in the United States, he is pictured on a beach south of San Francisco. On the back he wrote, “Here I am on the other side of the Pacific Ocean across from Shanghai. When I was there I felt how close you are, only water was separating us. On one side of that ‘lake’ I was standing, and on the other side were you. Something strangely hurt inside. I was longing to cross the water and come to you.”

Something strangely hurt inside. I read those words and wept. Now I was the one on the other side of that lake.

The weeks without him became months, but I could not shake the feeling that I had missed something, answers to questions I had failed to ask him—the journalist’s dilemma: knowing there is more to the story. So on August 31, 2003, I wrote to the Department of Justice in Washington:

I am seeking information under the Freedom of Information Act about my recently deceased husband, Theodore E. Streshinsky, who entered this country at San Francisco on March 5, 1947 by ship from Shanghai, China. He was born in Harbin, China on January 30, 1923, and entered the University of California at Berkeley as a student. He was charged with anti-American activities in the spring of 1954 (or perhaps a year earlier) and a deportation order was issued. A review hearing allowed him to stay. He finally received his citizenship, became an acclaimed photojournalist, and lived a long and useful life. I would appreciate any information that might help explain what happened to my husband.

A year passed. The ache of his absence remained, but I had stopped reaching out to his old school friends, or breaking locks on elaborately carved wooden boxes he had brought with him from China, which turned up nothing more important than a library card from St. John’s University in Shanghai. I busied myself getting Ted’s photographs ready for the archives at Berkeley’s Bancroft Library and then returned to work on a book left too long in the back parking lot of my mind.

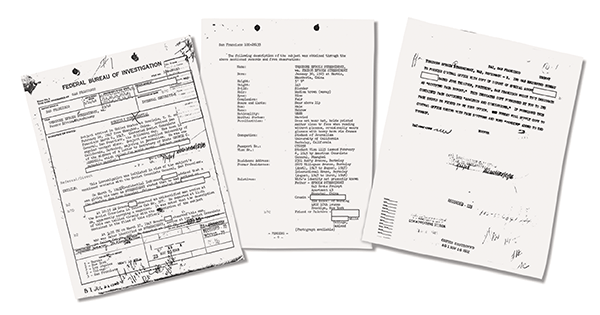

Late one afternoon in the spring of 2004, I came home to find a box sitting on top of my mailbox because it was too big to fit inside. From the Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, it contained a mass of photocopied sheets of paper—at least two reams’ worth—most pages stamped SECRET at least once and then this: ESPIONAGE.

In the summer of 1966, I married Ted Streshinsky in San Francisco’s city hall. That day we pledged to love, honor, cherish, and also create a partnership—career and life combined, full throttle. A day later, Ted drove south to the San Joaquin Valley, on assignment for The Saturday Evening Post to photograph Cesar Chavez, who was leading an assault on one of the nation’s entrenched problems: the plight of migrant workers. I stayed in the Bay Area long enough to finish an assignment of my own, then took the train to join Ted and the writer on the story, John Gregory Dunne, and his wife, Joan Didion, in Delano, headquarters of the new National Farm Workers Association. Joan picked me up at the station in Wasco. I remember asking whether she thought Chavez was, well, genuine. I don’t remember her answer, but in a book that was to prove prophetic, Dunne wrote, “In the summer of 1966 I went to Delano to see a town beleaguered by forces it did not understand, to see how and why Cesar Chavez had become the right man at the right place at what was, sadly, both the right and the wrong time.”

Delano was a mix of farmworkers, union reps, locals drawn to the struggle, some volunteers, a few veterans of the civil rights movement in the South, and observers like us. At the end of one evening in the union’s shabby storefront office, everyone, including Cesar and his wife, Helen, drifted into a circle, arms crossed. I felt embarrassed, an interloper. The anthem of the civil rights movement had spilled over to the migrant workers’ cause in California, and the song began: Nosotros venceremos—We shall overcome.

I was 31 that summer; Ted was 43. He had dropped out of graduate school at Berkeley, choosing photography over a PhD in political science, a decision he seemed to have made easily. I asked him once whether he had any regrets, and he said yes, he regretted not taking photographs in China when he was a teenager. By the time I met him, he was shooting for major magazines like Time and Life, where in those days people were getting their in-depth news. I had come to San Francisco from the Midwest with a journalism degree and a gnawing determination to report on the upheavals roiling the nation. A generation was struggling to push out of the complacency of the 1950s, old wounds had been reopened, new voices with new ideas were raised, and many of these crosscurrents were colliding in California. The stories were there for the telling.

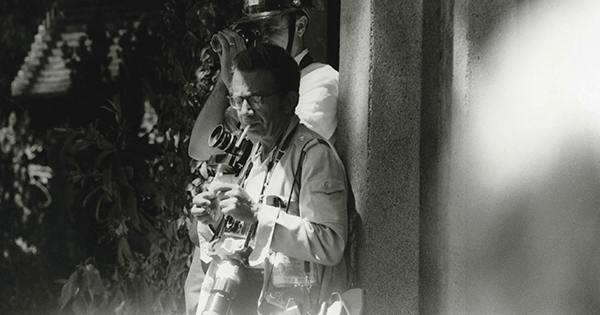

Ted Streshinsky on assignment in 1965, covering protests as a train passes through Berkeley with troops heading for Vietnam (Courtesy the Streshinsky family)

Inside San Francisco’s splendid Beaux-Arts city hall, a marble staircase sweeps dramatically from the grand rotunda up to the board of supervisors’ baronial hearing room. There, on the morning of May 13, 1960, the second day of sessions of the U.S. House Un-American Activities Committee—convened to look for Communist infiltration in Northern California—had begun. In his 2012 book, Subversives: The FBI’s War on Student Radicals, and Reagan’s Rise to Power, Seth Rosenfeld describes how students from Berkeley, the men dressed respectfully in jackets and ties, the women in skirts and blouses, arrived early and lined up to make sure they got seats. Only a few were allowed inside; eventually, some 300 students sat down on the stairway, resisting peacefully, according to plan. Four hundred San Francisco police officers took positions around the building. Another anthem from the civil rights movement lifted into the rotunda: “We shall not be moved,” the students sang, and the words echoed off the pink Tennessee marble. The police responded by turning fire hoses on at full blast, sending students tumbling over others below them on the stairs, screaming and crying. The cops then waded in, swinging clubs and dragging men and women down the stairs, herding them into vans and off to jail.

For me it was a wake-up call, marking the beginning of a ferment that would grow on the Berkeley campus and throughout the Bay Area during that tumultuous decade. I was editor of a company magazine, and one day Ted walked into my office, without an appointment but with the kind of innate courtesy that made it seem okay. He was slender and soft-spoken and had intensely blue eyes that, I was to learn, missed very little. That day he noticed John F. Kennedy’s book Profiles in Courage on my desk. What I noticed were the remarkable pictures in his portfolio, portents of the iconic photographs to come, which a 2015 book on documentary photography describes, in a section about Ted, as a “collection of images that dramatize the long-historical suppression of democracy by those who claim to uphold it.”

In December 1964, in what has been called the largest campus protest in American history, thousands of people rallied on the Berkeley campus in support of the free speech movement, which proposed that students had a constitutional right to organize politically on university property. Ted was in the crowd at Sproul Plaza, the center of the escalating action, as students surrounded folk singer Joan Baez and philosophy student Mario Savio, the passionate leader of the movement.

The following year, large-scale demonstrations against the war in Vietnam took place at the same plaza. One balmy evening in May, Ted and I joined a crowd on campus to hear comedian Dick Gregory’s bold and blunt antiwar teach-in. In August, Ted was assigned to photograph demonstrators attempting to stop a troop train going through Berkeley, and I went too. He pushed through the crowd, aiming for the tracks in front of a phalanx of police walking ahead of the engine. Men on the train were hanging out the windows, most of them jeering at the students with their “Stop the War Machine” signs. I looked at the faces of the young soldiers and wondered how many would come home.

The next day, too early, Ted got a call from an FBI agent who asked to see his film, in hopes of identifying protesters. Ted’s answer was uncharacteristically crude; I understood why he wouldn’t cooperate, but I didn’t yet understand his vehemence, or his disdain for the FBI.

I did know that J. Edgar Hoover—the powerful director of the FBI—had been searching for Communist sympathizers and subversives everywhere, especially among college students and professors. Berkeley seemed to top Hoover’s hit list. In 1967, according to Rosenfeld in Subversives, Hoover, intent on getting rid of UC President Clark Kerr, secretly gave California’s newly elected governor, Ronald Reagan, confidential reports about allegedly subversive students. Ted was at the UC Board of Regents meeting when Kerr was fired, and he photographed Reagan and Kerr together, but with their backs turned to each other.

We had settled into a house in the Berkeley hills not far from where Ted’s seven-year-old son, David, lived with his mother. Our son, Mark, was born the summer that Jimi Hendrix set his guitar on fire at the Monterey Pop music festival. A hundred thousand young people were descending on San Francisco, many in fact with flowers in their hair and looking for something missing in their lives. And the Black Panthers, headquartered in nearby Oakland, were gaining traction as a counter to Martin Luther King Jr.’s nonviolence movement. Ted covered them all.

Out-of-town writers sometimes stayed with us in a room over our garage, and now and then a few errant flower children would turn up with sleeping bags and copies of The Diary of Anaïs Nin or Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha. They saw themselves as free spirits searching for a world without strictures.

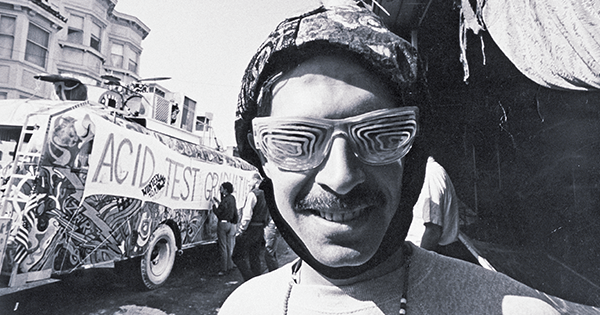

Tom Wolfe came looking for Ken Kesey, whose band of Merry Pranksters had been spreading the gospel of LSD (it was legal until 1970). Kesey had dubbed the drug “acid” and had promoted several acid-trip festivals, one in the San Francisco Longshoremen’s Hall, where the Warlocks (later the Grateful Dead) blasted their music and spiked the Kool-Aid with LSD. The Pranksters, who included Stewart Brand, Wavy Gravy, and Neal Cassady (the inspiration for Dean Moriarty in Jack Kerouac’s On the Road )—were harbingers of not just a new drug culture, but also of an inchoate take on life itself. When Wolfe showed up, Kesey—in jail for possession of pot—was about to get out after making a deal with local law enforcement agencies to publicly denounce the evils of LSD.

Wolfe, who had his own ideas about sartorial splendor, appeared in a blue silk blazer and a tie with clowns on it. Ted’s standard outfit was khakis and a safari jacket. Both were seriously underdressed when they set off to cover, for The New York Herald Tribune’s Sunday magazine, Kesey’s “Acid Test Graduation,” in which the Pranksters would announce their intention to do all of their future tripping without the aid of LSD. The event was held at the Warehouse, the scabrous garage of a defunct hotel (for old pugilists who had taken too many hits to the head), in San Francisco’s Tenderloin. From the ceiling hung a wonderfully sardonic banner: “Cleanliness Is Next.” The music was loud, and the dancers, Tom would write, looked like “freaking faeries out of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, dueling shirts and long gowns of phosphorescent pastels like the world never saw before.” In a copy of the book that resulted, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Tom would inscribe, “For Ted! Who captured it all in full-freaking Day-Glo better than anyone before or since; with thanks and admiration.”

In the spring of 1967, Joan Didion set out with Ted to scour Haight-Ashbury for a story on the hippie incursion, searching for the center of an ever-shifting scene. At night, we would project Ted’s pictures on our living room wall. Ted shot some of the period’s defining moments: in Golden Gate Park, kids making giant soap bubbles, and a pretty hippie girl, hair flying as she smiled and danced alone, oblivious, eyes closed as if in a trance—a poster child for the Summer of Love. The photographs captured all the pent-up, unfettered, acid-induced desires of a generation, writhing and gyrating, all flashing lights over the hard-rock beat of Janis Joplin and bands like her Big Brother & the Holding Company. The Diggers were offering free food in the park. A crisis center for runaway children was established in the Haight. What had been love and peace and kite dreams was fueled by LSD and pot, then by amphetamines and heroin. Joan’s article, with Ted’s photographs, appeared in The Saturday Evening Post under the title “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” from the W. B. Yeats poem, and signaled that something had gone very wrong, the center was not holding; the old rules had been thrown away, and there was nothing to replace them.

Two years later, Ted’s focus shifted to the Berkeley campus, where a group of young dissenters had created a “People’s Park” on an unused plot of land owned by the university. Officials moved to take it back, triggering a riot. Governor Reagan lost no time calling in the National Guard and imposing a curfew. I was pregnant with our daughter Maria; the day the Guard came marching down Shattuck Avenue in full combat gear, Ted’s mother and I happened to be nearby and stood watching. I’d never seen anything like it, but she had, all too often in her lifetime. She held hard to my arm, muttering “terrible, terrible.”

What became known as the People’s Park riots coalesced into the long-brewing Vietnam war protest and the free speech movement. Ted, with a gas mask supplied by Time Inc., made his way to the second story of a building that overlooked Telegraph Avenue and took one of the most memorable images of the era: a girl in white hippie garb, handing out antiwar leaflets while surrounded by California National Guardsmen, their bayonets pointing at her.

The other day, I pulled some of our old daybooks off a shelf in the basement of our house, spread them out on top of the washer-dryer, and got lost in the shorthand of our lives. At 10 in the morning one December day, Ted photographed UC–Berkeley physicist Luis Alvarez for Time magazine, and at 10 that night he went into North Beach in San Francisco to photograph a topless waitress, also for Time. On the evening of Martin Luther King Jr.’s funeral, several angry young black men shot and killed a young white bus driver named Martin Whitted. Redbook magazine assigned me to do a story on Whitted’s wife and their three young daughters, with Ted taking the photos. The following year, the magazine asked us to work together on a story about a Navy nurse, a lieutenant who was court-martialed for appearing in uniform in an antiwar demonstration in San Francisco. Even when we weren’t collaborating, Ted read all my first drafts, questioning facts and reasoning, but never my style. I did the second edit of his photos, poring over contact sheets and stacks of color transparencies. Our stories followed the leitmotifs of the century—war, race, migration, and the stress fractures that occur when democracy collides with capitalism.

Ted’s parents grew up in Odessa, on the Black Sea, a Ukrainian city with a long history of Jewish pogroms. After the First World War ended in 1918, the country was torn by the civil war between the Bolsheviks and the Czarists and soon became a Soviet socialist republic. The turmoil created economic chaos and famine, quickly followed by the search for scapegoats. Jews began to look for safe havens. Almost immediately after Reva and Efroim Streshinsky were married in Odessa in 1921, they climbed aboard the Trans-Siberian Railway and traveled under Ukrainian passports more than 6,000 miles to Harbin, China.

More Russians than Chinese lived in Harbin. Efroim, who was a chemist, established a company that produced pharmaceuticals and sold patent medicines, cosmetics, and French perfumes. Ted was born in 1923. He was tutored until his junior year, when he enrolled in a Russian high school staffed by university professors who had fled the Soviet Union. In 1937, when the Japanese confiscated Efroim’s laboratory, the family moved to Tientsin, into an apartment above a new drugstore Ted’s father had opened. There Ted entered a British school to learn English and prepare for the Cambridge University local examinations; he needed both to be admitted to a university in the United States, the obvious choice, since Europe was engulfed in the Second World War. Ted applied to UC–Berkeley in 1939, when he was 16, and was accepted.

But the Japanese were on the march and soon arrived in Tientsin. To escape them, the family moved to Shanghai, taking an apartment on the top floor of a new Art Deco building in the French Concession, an area leased by China to France and governed by French laws. Having to start over in Shanghai delayed Ted’s departure for Berkeley. Instead, he enrolled at St. John’s, an Anglican university founded by American missionaries, and continued to work on his English. When Japanese bombs fell on both Pearl Harbor and the International Settlement in Shanghai on December 7, 1941, and the United States entered the war, it was clear that Ted would be in China for the duration.

At war’s end, Ted was working as a reporter for the North China Daily News, a venerable British paper that renewed publication after the Japanese defeat. In a book of yellowed clippings, I found a story dated January 15, 1947, with Ted covering the final arguments in a trial before a four-man U.S. military commission of 21 Germans accused of war crimes, “the counterpart of the German SS, Gestapo and the Nazi party in this part of occupied Asia.” Three days later, he was back to see the judges issue sentences, which ranged from five years to life at hard labor. It was exciting, he once told me, to be involved in the rush of news from the outside world, after having endured years of Japanese censorship.

I once asked Ted if I could check, under the Freedom of Information Act, to see whether he had an FBI file. His answer was definite: he was only a student, he wasn’t important, it wasn’t worth my time. The pile of pages that the FBI later sent me seemed to contradict him. By now the papers had become a presence in my life, having taken up residence in a file cabinet in a corner of my office. My feelings were ambivalent: I wasn’t sure how much Ted would want me or anyone else to know. So I stalled. I traveled. I launched into writing the long-delayed book. But finally there was nothing to do but lug the file—12 pounds’ worth—into the dining room, where I could spread it out on the table and begin to read.

Ted’s photo of one of Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters and their school bus, made famous by Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (Courtesy the Streshinsky family)

In February 1947, at age 24, Ted boarded the SS General M. C. Meigs, a converted American troop ship destined for San Francisco, where at last he would enroll at Berkeley. He stood on deck, he told me, leaving behind his past and his parents as the skyline of Shanghai disappeared. He couldn’t know whether he would see them again.

On March 5, the ship sailed under the Golden Gate Bridge and dropped anchor in the bay. His first night in the city, Ted stayed at the Hotel Whitcomb on Market Street. The next day, a Friday, he put on a suit and tie and took a Yellow Cab to the Soviet consulate on Divisadero Street. He had no idea that an FBI agent was in a window across the street, photographing every stranger who came and went. Ted returned the following week, three more times in July, and once each month through November. The frequent visits caught the attention of Harry Kimball, special agent in charge of San Francisco’s FBI field office.

Ted spent the next few months across the bay, settling into the International House on the Berkeley campus, attending classes, and taking care of the paperwork for the student visa required by the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). One weekend, he boarded a bus to Seattle to see a woman he had met onboard the Meigs named Bernice Thompson—Bernie—who had spent several months in China working for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration helping to establish co-ops in the Chinese countryside. She happened to be a member of the Communist Party, and Ted did not yet know that Hoover, Reagan, Representative Richard M. Nixon, and Senator Joseph McCarthy were gearing up to convince Americans that communism, as practiced by the Soviets and the Chinese, was a deadly contagion that had to be eradicated.

On May 14, 1948, the San Francisco FBI office sent the first Ted memorandum to Washington, marked secret and strictly confidential: “Theodore Efroim Streshinsky” appeared at the top of the page, followed by a paragraph that was to be repeated time and again as file 100-28133 grew exponentially:

Subject … arrived San Francisco March 6, 1947. Contacted Soviet Consulate General, San Francisco, the following day. Has been in regular contact since. Subject now enrolled University of California, Berkeley, majoring in journalism. He was one of the signers of a letter to Secretary of State George C. Marshall, which called for world peace. … This investigation was initiated in view of the subject’s continued contacts with the Soviet Consulate General.

In a follow-up report, a note explained that Ted entered the United States on a Soviet passport that was to expire in less than a year. When the INS asked him to list all the jobs he had held in China, he dutifully included “Translator, English to Russian, for TASS, the Soviet News Agency.”

The Washington FBI’s reaction to the report was immediate: “You will prepare without delay a 5” × 8” white card. … [T]he caption of the card … must be kept current at all times. … Very truly yours, John Edgar Hoover, Director.”

The white security index card was integral to Hoover’s byzantine paper world. By the mid-1950s the index would hold the names of 26,174 people “who would be dangerous or potentially dangerous in the event of … serious crisis involving the United States and the U.S.S.R.,” Rosenfeld notes. If that crisis came, the FBI was to detain these people immediately. Some 200 of the names were in a special category: judged the most dangerous, they would be the first to be rounded up. It didn’t take long for Ted’s file to be flagged “Espionage” and his security index card to be marked “Special.”

The TASS connection was a flashing red light to the FBI, though Harry Kimball did point out that it would be peculiar for an aspiring espionage agent to admit to the INS this obvious Communist connection. I thought Kimball might have pointed out the same problem with Ted’s frequent visits to the Soviet consulate; his passport, after all, had to be renewed before the first of the year, and he had to be sure he could join his parents in the Soviet Union if they could find no way to join their only child. He was on a student visa, to be renewed yearly, and he could not stay in school forever. He would have felt the need to maintain friendly relations with the Soviets, to keep all options open for himself and his parents. The FBI timed each of his visits to the consulate; occasionally he stayed for an hour or two, more often it was for 10 or 20 minutes, as if he was returning to check on something—an answer to a question he had asked. Even as Ted had been crossing the Pacific, the United Nations was debating the possibility of a new Jewish state in Palestine, which could be a way station, another option, for Ted’s parents in Shanghai.

Unaware of the storm about to break over him, Ted married Naomi Gottlieb, an American graduate student whom he had met at the International House. She was also from a Jewish family with roots in Russia. The couple moved into an apartment on Bowditch Street near the campus. Kimball’s agents went through their trash, had the post office collect all return addresses, and tapped the telephone. When these maneuvers produced no promising leads, the FBI fell back on one of its illegal “black bag” operations, breaking into the apartment and photographing every page of Ted’s address book and a stack of other documents. The agents left with a whole new set of leads.

This blast of names was fired off to FBI field offices around the country: Los Angeles, New York, Savannah, St. Louis. In Seattle, a classmate from China told an agent that Ted was a “Soviet enthusiast,” but so was she at that time because, she explained, the Soviet Club was a good place to go for fun, to attend plays and dances. Another school friend remembered that Ted had been critical of aspects of Soviet communism and was disgusted by the corruption of Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Chinese government. FBI agents investigated Ted’s new in-laws in their old neighborhood in New York and in their new one in Los Angeles. Hoover signed a humble letter to the CIA asking that they investigate Ted’s father in Shanghai.

By June 1949, the San Francisco bureau had amassed enough information for a 75-page report. Friends who had written to Ted from Russia, Italy, India, and Belgium had been tracked down; the mail cover had yielded 88 separate leads, every one followed up by the indefatigable agents. The phone tap turned up 33 new leads, and the trash added a couple of chatty letters and a copy of a Russian magazine called New Time. The CIA reported that the subject’s father in China “allegedly cultivates influential Soviets when possible.” Page 62, titled “Analysis and Conclusions,” began: “It will be noted that no information reflecting espionage activity in the United States is reflected in this report or previous reports.” Along with the copy mailed off to Washington headquarters, the San Francisco office sent a copy to the INS, which had recently cleared Ted for an extension of his student visa.

Hoover, or someone acting for him, was livid. A message went to Kimball in San Francisco directing him to send an agent to the INS office immediately, to “recover and destroy” page 62 of the report—which had also suggested that “there are indications that subject may not be a Soviet agent”—and to advise that the report should end on page 61 with the notice “pending.” The message encouraged the INS director in Washington to withdraw the extension of Ted’s student visa because of “derogatory information” in the FBI’s possession.

Ted could not have known anything about recover-and-destroy orders in the name of J. Edgar Hoover, or the security index cards, or the lengths to which the FBI had already gone to try to prove him a foreign agent. But he had to know something was desperately wrong when he received notice from the INS that the recent visa extension had been “granted inadvertently” and that he should prepare to leave the country by the end of the month. When he asked for a reason, the bureaucrats repeated the phrase they had been given: “derogatory information.” Nothing more. All Ted could do was to appeal.

Photocopied pages from the 12 pounds of documents in Ted Streshinsky’s FBI file, released under a Freedom of Information Act request (Courtesy the Streshinsky family)

Whenever he was worried about something, Ted had trouble going to sleep; it annoyed him that I could nod off on the way to my pillow. But when I am troubled, I wake in the early morning hours, thoughts churning. These past months, having finally released the 60-some-year-old FBI records from my file cabinet, I find myself in my living room, watching the sunrise slowly light San Francisco Bay. I imagine the forces converging on Ted in those years before I knew him, and it makes me heartsick.

On January 30, 1950, his 27th birthday, he appeared for an interview at the INS building in San Francisco, where he swore under oath that he had no connection to the Communist Party, that he believed in the form of government of the United States, and that he wanted to become an American citizen. When one of the examiners asked outright whether he had been involved in espionage, Ted surely was jolted.

The INS director sent the report on Ted’s interview to the director of the FBI for comment. The response: “This Bureau’s investigation is continuing.” However, “the Bureau defers to your judgment regarding any action you might desire to take.”

In December, 11 months after the INS interview, Ted learned that his appeal had been rejected, and he would have to leave the country in two weeks’ time. Not long after Ted died, I met with his great friend from grad school, Victor Rosenblum, a long-time law professor at Northwestern and a distinguished legal scholar. He said that Ted hadn’t told him about his immigration problems until the deportation notice; some of their professors at Berkeley rallied to his support, and Vic found a Washington, D.C., immigration lawyer known for taking on tough cases. From the files, I note that at about this time the attorney advised Ted to renounce his Soviet citizenship and return his passport, then to apply for a change of status to Displaced Person. But that left Ted in a bind—if he wanted to see his parents again, he had to hang on to the Soviet passport as long as they needed theirs. They were still in China, hoping that Israel would open its borders before the INS threw Ted in jail and then out of the country.

On January 12, 1951, the San Francisco FBI field office sent off yet another of its ritual Ted reports to Hoover, with an even stronger suggestion that Ted be cut free: “Extensive investigation of subject has been conducted over approximately three years,” it said, “without establishing definite espionage activity.” The tide was turning in Ted’s favor. His security index card had been removed from the special section. Even so, the Washington bureau refused to close the case, and agents found themselves doing second interviews of old leads. One of Ted’s Shanghai acquaintances reported that she had run into him on the street and he seemed “afraid of his own shadow.”

Little wonder that Ted was frantic; time was running out. By the end of March he had been in the United States illegally for three months, so he would have been looking over his shoulder.

Then, suddenly, action in Shanghai. Early in April, Ted’s parents boarded a plane chartered to take a contingent of Russian Jews to the new state of Israel. The dates aren’t precise, but it looks as though Ted immediately renounced his Soviet citizenship, returned his passport, and became officially stateless—just before he was arrested on May 18 and jailed pending deportation. He was released that day on a $500 bond, and he returned to classes at Berkeley to continue studying politics while he waited to see whether he could get a hearing and have the deportation order rescinded.

By February 1952, he was still waiting when the San Francisco FBI field office reminded the director that its exhaustive search had failed to find any evidence of espionage and requested permission to call Ted in for a “thorough and comprehensive interview.” They had scores of man-hours invested in him; maybe they could shake out some useful information. Hoover agreed, and on the afternoon of March 13—almost exactly five years after Ted arrived in San Francisco—he appeared at the San Francisco field office. Ted began by saying he understood the government had received derogatory information about him and he appreciated the opportunity to discuss the matter personally. He could not have known the extent of the investigation or that it was the FBI that had caused his student visa to be denied. Neither did he know who had provided the derogatory information—he assumed that it was someone he knew from China who had given in to the temptation to offer a name in return for a favor.

Special agents, in three different teams of two, quizzed Ted on seven different days through March and April, each session lasting from 1:30 to 5:00 in the afternoon—more than 24 hours in all. He answered every question thoroughly. He explained that the Soviet Club was a place to go see plays, have dinner, socialize. He told them about the Jewish club, went into detail about the responsibilities of the staff at TASS, including his duties as a translator from English to Russian. He listed everyone, including a typist in her 60s whose last name he couldn’t remember. When it was all over, the agents concluded that Ted had seemed cooperative—and that he hadn’t told them anything they didn’t already know.

In 1953, the security index card for Theodore E. Streshinsky was withdrawn altogether, and someone in the FBI hierarchy (the name is redacted) strongly suggested that the case be closed. The last three papers in Ted’s file, dated May 18, June 3, and June 8, 1954, seem to be routine notifications from the Washington bureau of the FBI in response to INS forms indicating that Efroim and Revecca Streshinsky had applied for permission to enter the United States and that Ted Streshinsky had requested a suspension of deportation. I assumed that was the end of it. It was not.

When I finally returned the bulky files to their cabinet, I happened upon a smaller, personal file I had never noticed. It contained Ted’s parents’ Israeli passport, showing that they entered the United States in January 1958, along with a sheaf of correspondence between Ted and the immigration lawyer in Washington. My heart sank, and I can almost hear Ted say to me, with the wry grin he saved for certain occasions, “Well, you wanted to know.” The deportation order had remained stubbornly in force; between 1954 and 1959, Ted—now stateless—was subjected to four more hearings as he sought to have the deportation order lifted. Three times his appeal was turned down on the basis of “confidential information.” The FBI had not closed Ted’s case after all.

By 1955, Ted must have lost hope, because he applied to New Zealand for permanent residency. He was turned down without a reason. It had taken his parents more than 10 years to join him in the United States; now he was the one with no place to go. Liberation arrived in 1959, in the guise of a new INS regulation that abolished confidential information as a reason to deny the suspension of deportation. “This is a vitally important change for the good,” Ted’s D.C. lawyer jubilantly wrote. In May 1959, 12 years after he had arrived in San Francisco, the deportation order was voided, his case reopened, and Ted was at last allowed to become a citizen.

I had not known that Ted traveled to this country on a Soviet passport, that he worked for TASS, or that as soon as he arrived in San Francisco, he went straight to the Soviet consulate, and in the process did himself in. The FBI couldn’t resist; soon enough, it became the keeper of the elusive “derogatory information” that plagued him for so many years. Ted died without knowing that none of the scores of friends and acquaintances interviewed had had a derogatory word to say about him.

I do have to give J. Edgar Hoover some credit. If his agents hadn’t spent all those zillions of hours writing endless reports, based on information gleaned from trash bins, phone taps, break-ins, and all those interviews, I would never have known what happened to Ted during those missing years. Not that they got everything right. Ted was, after all, exactly who he told me he was: just a student, not important enough for an FBI file. John Dunne had called Cesar Chavez “the right man at the right place at … both the right and the wrong time.” So too was my husband.