The Feminine Arts

A writer explores the elation and difficulty of making art while female

Art for the Ladylike: An Autobiography Through Other Lives by Whitney Otto; Mad Creek Books, 311 pp., $23.95

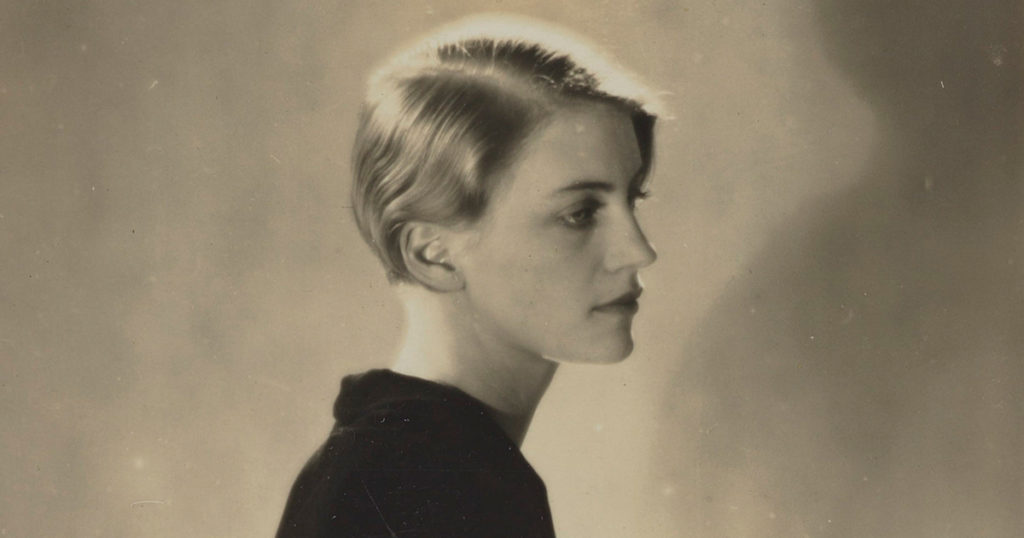

Lee Miller—a former fashion model, surrealist muse, and war photographer—was living in Hitler’s private apartment in Munich when she learned of his death. There is a photograph of Miller in Hitler’s bathtub; in the photo, her army boots are crumpled on the floor, and a formal portrait of the Führer leans against the tiled wall. She photographed the final two years of World War II for British Vogue, clad in fatigues, following American troops into battle, and capturing images of Nazi suicides and death camps.

In 1932, Man Ray, who often photographed Miller and was her sometimes lover, had gone looking for her in the streets of Paris, armed with a gun. He didn’t find her, and, later that night, took a self-portrait called Suicide, 1932, in which he has a bottle of poison, a noose around his neck, and a pistol aimed at his head. (Despite this incident, Miller and Man Ray were lifelong friends.)

Picasso painted Miller six times, she was filmed by Jean Cocteau, and she appeared on the covers of fashion magazines after Condé Nast, namesake of the publishing empire, saved her from falling into a New York City street in 1926.

At the age of 40, Miller married her second husband, had a child, and quit public life. Around that time, afraid of dying in childbirth, she told her husband, “I didn’t waste a minute of my life—I had a wonderful time … if I had it to do over gain I’d be even more free with my ideas, with my body and with my affections.”

In Whitney Otto’s essay collection, Art for the Ladylike: An Autobiography Through Other Lives, Otto gives a rejoinder to Miller’s statement: “Get the fuck out of here.” For Otto, Miller was an archetype for the successful female artist and adventurer, who transgressed the restrictions of a sexist society without shame. And even Miller wished she had been less restrained.

In her book, Otto explores the lives of female photographers, mostly from the first half of the 20th century. She describes the art they made and how they made it. She examines their love affairs and marriages, their politics and responses to motherhood. Otto’s own life—her Greatest Generation parents and California childhood, her work to become a novelist, her marriage and motherhood, her bonds to the art that sustains and inspires her—is braided into the photographer narratives. It illuminates how the lives and art of women such as Miller, Imogen Cunningham, Sally Mann, and Ruth Orkin guided Otto’s ideas about how to be a woman who makes art.

It turns out that it is not easy to be a woman who makes art.

Miller didn’t publish photographs after she had a child.

After Cunningham—who had earned a degree in chemistry, studied in Europe with the “foremost photo-chemist of his time,” and had her own studio—married and had children, her artistic pursuits were limited to the domestic sphere. One of her most famous images is Magnolia Blossom, 1925; the tree grew in her yard. Cunningham’s husband divorced her after 19 years of marriage, when she took an assignment from Vanity Fair that he felt was inconveniently scheduled.

As for Orkin, “in 1939, at age seventeen, she hopped on her modest little bicycle and pedaled from Los Angeles to the New York World’s Fair. Alone,” writes Otto. Orkin worked for MGM studios, but left when she couldn’t join the Cinematographers Union because she was a woman. She traveled extensively and photographed movie stars, famous musicians, and Albert Einstein. Orkin made popular movies. Then, after Orkin became a mother, she took a series of photographs, over several decades, out the window of her apartment that faced Central Park. “Now that I think about it, I don’t see how anyone but a housewife could have got all this done,” Orkin wrote in the introduction to her 1978 book, A World Through My Window.

Twice Otto cites the writings of the Guerrilla Girls, a group of anonymous female artists. The first time, she quotes one of the poets in the group without comment:

The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist, 1988

Working without the pressure of success.

Not having to be in shows with men.

Having an escape from the art world in your 4 freelance jobs.

Knowing your career might pick up after you’re eighty.

Be reassured that whatever kind of art you make it will be labeled feminine …

In the epilogue, Otto, whose debut novel, How to Make an American Quilt, was a New York Times best seller and was adapted into a movie, reprises the text but adds her own ironic annotation. “If you write a novel with the world ‘quilt’ in the title,” she writes, “then you deserve to be dismissed by the men who are dragged to your readings (as you’ve been told more than once) by their wives or girlfriends.”

Otto writes critically about the roles that love and marriage often force upon female artists. Even in cultural circles where men considered themselves politically progressive, marriage made it harder for women to make art. “Artistic couples are a pretty standard fantasy, art enhanced by an unconventional love affair,” she writes. “Muses and mistresses and lovers. Man Ray and Lee Miller and Kiki. Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore. Weston and Modotti and Mather. Stieglitz and O’Keeffe … No matter how much the Bohemian Class tries to explode the idea of marriage, they all end up married (or ‘married’) anyway, in one way or another.”

As a young woman, Otto had misgivings about the feasibility of romantic partnership and motherhood balanced against her artistic ambitions. Her own glamorous mother worked in advertising in midcentury Pasadena, California. “I knew my mother didn’t want to be home with us kids,” she writes. “We weren’t interesting enough, motherhood wasn’t interesting enough.”

Otto writes about two of her own relationships: one during her university days, with a musician who required that Otto make sacrifices for his artistic aspirations, and her marriage to a man she refers to as “J.” When the couple had a son, J. became a stay-at-home dad. “Once, when driving with our son, who was about six at the time, he asked me if a male friend of ours was coming over to the house,” Otto writes. “I said, No, he has to work. Our son gave me a sly smile, like he knows he’s being played with, and said, going along with the joke he thinks he’s getting, ‘Boys don’t work.’” Otto writes that she realized at this moment that her son had been pulled out of mainstream culture—one that told both women and men to limit themselves, to contort themselves into claustrophobic poses—and she was relieved.

“Being outside the mainstream is the very short, simple answer to How One Becomes an Artist; that is to say, one doesn’t become an artist or writer in order to move into the fringe,” Otto writes. “Look on the edge of any social map to find: You are here.”

It is not easy to be a woman who makes art, but reading about the lives of these female artists, one begins to feel like it is the only way to live. To be a woman who makes art is to be a woman who takes her own freedom, who re-invents what a woman’s life can be, who reveals that the female experience is meaningful. Who wouldn’t want, like Miller, to be more free with her ideas and affections?