The First President To Be Impeached

Andrew Johnson beat the charges against him by a single vote, but what did the nation lose?

February 25, 1868, Washington, D.C.

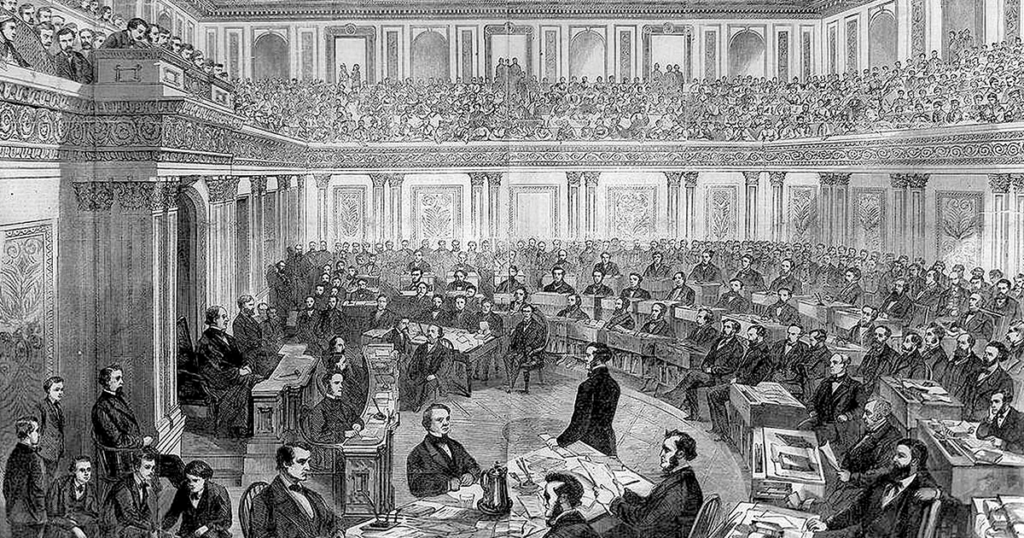

A cold wind blew through the city, and the snow was piled in drifts near the Capitol, where gaslights flickered with a bluish glow. Throngs of people, black and white, waited anxiously outside or pressed into the long corridors and lobbies.

At quarter past one in the afternoon, the doorkeeper of the U.S. Senate announced the arrival of Pennsylvania Rep. Thaddeus Stevens. Weakened by illness, Stevens was carried aloft in his chair and helped to stand upright, and after taking a moment to gain his balance—born with a clubfoot, he wore a specially made boot—he linked arms with Rep. John Bingham of Ohio, who had accompanied him to the Senate. The two men strode with slow dignity down the main aisle of the chamber.

The packed galleries were so hushed that there was no mistaking what Stevens, emaciated but inexorable, had come to say. He formally greeted Benjamin Wade, also of Ohio and the Senate’s presiding officer, and then pulled a paper from the breast pocket of his dark jacket and read aloud, each word formed with precision.

“In obedience to the order of the House of Representatives, we appear before you, and in the name of the House of Representatives and of all the people of the United States.

“We do impeach Andrew Johnson, President of the United States, of high crimes and misdemeanors in office.”

Just the day before, the House had voted, 126 to 47, to undertake this extraordinary step: the first-ever impeachment of an American president. No one dared to speak.

Stevens had been pushing hard for Johnson’s impeachment for more than a year, but previous attempts had failed. Now congressional Republicans believed they no longer had a choice: impeachment was the only way to stop a president who refused to accept the acts of Congress, who usurped its prerogatives, and who, most recently, had violated a law that he pretended to wave away as unconstitutional. But for people like Stevens, the specific law that President Johnson had violated—something called the Tenure of Office Act—was merely a legal pretext; Johnson should have been impeached by the House and brought to trial by the Senate much earlier, and he had been lucky to have escaped this long.

That is why Stevens was considered inexorable. Then again, so was the president, who had been heard to say, “This is a country for white men and, by G–d, so long as I am President, it shall be a Government for white men.” That vow offended Stevens to the core. He and his fellow impeachers believed that the war to preserve the Union had been fought to liberate the nation once and for all from the noxious and lingering effects of slavery. “If we have not yet been sufficiently scourged of our national sin to teach us to do justice to all God’s creatures, without distinction of race or color,” Stevens had declared at war’s end, “we must expect the still more heavy vengeance of an offended Father.”

“‘All men are created free and equal’ and ‘all rightful government is founded on the consent of the governed,’” Stevens had also insisted in 1867. “Nothing short of that is the Republic intended by the Declaration.” He had fought to create a world where blacks and whites lived in harmony and equal citizenship. Discovering that the place he had chosen for his burial would not inter black people, he immediately sold the plot and bought one in an integrated cemetery. He then wrote his own epitaph: “Finding other cemeteries limited as to race by charter rules I have chosen this that I might illustrate in my death the principles which I advocated through a long life, equality of man before the Creator.”

But President Johnson had sought to obstruct, overthrow, veto, or challenge every attempt by the nation to bind its wounds after the war and create a just republic from the ashes of the pernicious “peculiar institution” of slavery. To be sure, slavery had been recently eradicated—by proclamation, by war, and by constitutional amendment—but its malignant effects stalked every street, every home, every action, particularly but not exclusively in the South. “Peace had come, but there was no peace,” a journalist would write.

Stevens continued to read from the paper he’d pulled from his coat pocket. The House would provide the Senate—and the country—with specific articles of impeachment in the coming days, but in the meantime, he added, “we demand that the Senate take order for the appearance of said Andrew Johnson to answer said impeachment.”

“The order will be taken,” Senator Wade replied.

It sounded like a death sentence, an onlooker observed, though not to the young Washington correspondent Mark Twain. “And out of the midst of the political gloom,” Twain rejoiced, “impeachment, that dead corpse, rose up and walked forth again!”

“Andrew Johnson was the queerest character that ever occupied the White House,” one of his colleagues remembered. As Lincoln’s vice president, thrust into the presidency after Lincoln’s assassination, Johnson earned the hatred and opprobrium of most Republicans, particularly those members of Lincoln’s party in Congress who initially hoped that he had become one of them. Although he had been a Democrat, he’d been Lincoln’s running mate, after all. But just six weeks after the assassination, Johnson swerved away from what many considered to be Lincoln’s program for reconstruction and the fruits of a hard-fought, unthinkably brutal war.

Still, impeachment? That was new territory even for a president who had been widely reviled, as other chief executives had been: Franklin Pierce, old John Quincy Adams, and on occasion Lincoln himself. Yet never before had Congress and the country been willing to grapple directly with impeachment, as defined in the Constitution. Then again, never before had the country been at war with itself, with more than 750,000 men dead, at the very least, and countless men and women, black and white, still dying or being murdered, in Memphis, New Orleans, and other cities and in the countryside in Mississippi, Georgia, South Carolina, Florida, Texas, and Alabama.

And so in 1868 the Congress and the public would have to consider the definition of a high crime, the meaning of a misdemeanor. It was bewildering. “The multitude of strangers were waiting for impeachment,” Twain noted. “They did not know what impeachment was, exactly, but they had a general idea that it would come in the form of an avalanche, or a thunder clap, or that maybe the roof would fall in.”

No one knew what the impeachment of the president of the United States would look like or what grounds, legal or otherwise, would suffice. No one knew partly because the Constitution provides few guidelines beyond stipulating, in Article II, Section 4, that a federal officer can be impeached for treason, bribery, or a high crime or misdemeanor. The House of Representatives shall have the sole power of impeachment, the Constitution says, and a simple majority of members can vote to impeach. The Senate shall then have the sole power to try all impeachments, and if there is a trial of the U.S. president, the chief justice of the Supreme Court shall preside over it. No person shall be convicted without the concurrence of two-thirds of the members of the Senate present. A conviction requires the person be removed from office. As for further punishment, the convicted person may or may not be prosecuted by law. That’s pretty much it.

If the president was to be impeached for treason, bribery, or a high crime or misdemeanor, then “high crime” had to be defined. Originally, the crime warranting impeachment was “maladministration,” but James Madison had objected; the term was hazy. Yet “high crimes and misdemeanors” is fuzzy too. In Federalist No. 65, Alexander Hamilton clarified, sort of: a high crime is an abuse of executive authority, proceeding from “the abuse or violation of some public trust.” Impeachment is a “NATIONAL INQUEST into the conduct of public men.” Fuzzy again: Are impeachments to proceed because of violations of law—or infractions against that murky thing called public trust?

But surely if the only crimes that were impeachable were “high,” then the Founding Fathers must have meant “high misdemeanors” as well. For a misdemeanor is a legal offense ranked below that of a felony. Was a president to be impeached for any misdemeanor—like stealing a chicken—or did it have to be something, well, higher? Yet a man in a position of power must be held accountable for his actions. And so the Founders outlined a way to adjudicate accountability—to provide a way to maintain responsible and good government, which is to say to preserve the promise of a better day.

Still, the impeachment of a president seemed no less revolutionary, no less confusing, and no less terrifying for that. Impeachment was the democratic equivalent of regicide: Benjamin Franklin had said that without impeachment, assassination was the only way for a country to rid itself of a miscreant chief executive who acted like a king.

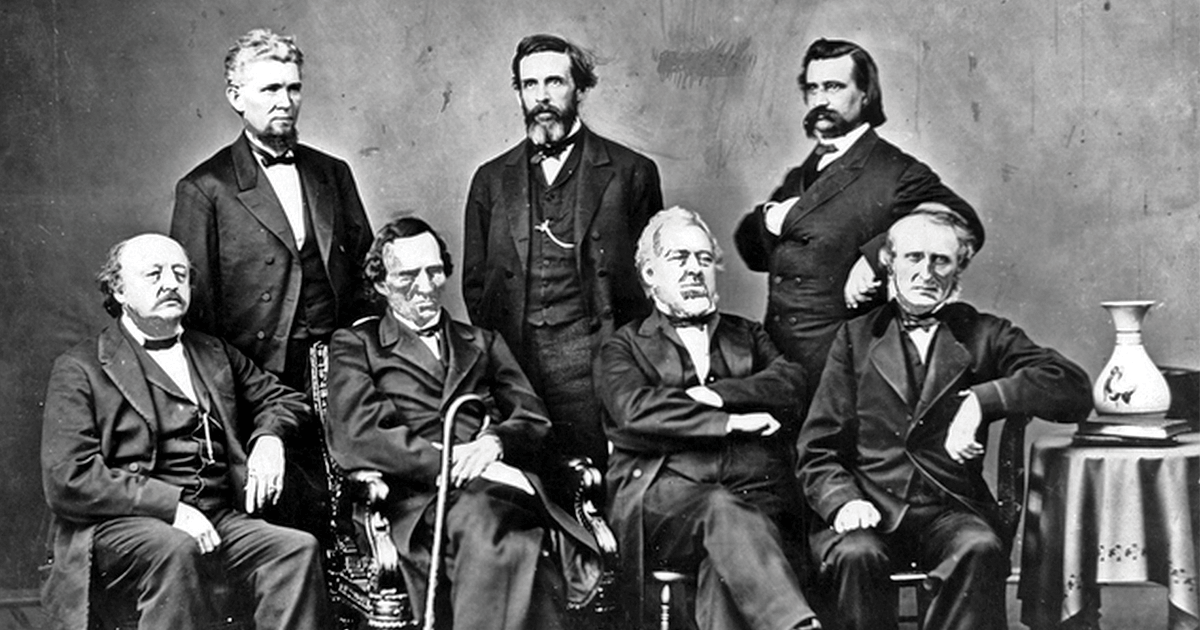

The House impeachment committee, photographed by Mathew Brady. Seated: Benjamin F. Butler, Thaddeus Stevens, Thomas Williams, John A. Bingham. Standing: James F. Wilson, George S. Boutwell, John A. Logan (New York Public Library)

President Johnson’s unprecedented impeachment thus presented knotty constitutional issues—and at a very specific, very difficult time in American history. The Appomattox peace agreement was not yet three years old, and the country was still seeking moral clarity, and more particularly, the restoration of the Union, while a popular if unreadable general, Ulysses S. Grant, waited in the wings to be nominated the next chief executive. Driven by some of the most arresting characters in American history—Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, Sen. Charles Sumner and Rep. Benjamin Butler, the abolitionist Wendell Phillips, and especially Thaddeus Stevens—the impeachment of Johnson was one of the most significant moments in the nation’s short history.

For there were concrete, burning questions about the direction the country would take: Under what terms would the states of the former Confederacy be allowed to reenter the Union? Should those states that had waged war against it be welcomed back into the House and the Senate, all acrimony forgotten, all rebellion forgiven, as if they had never seceded? President Johnson argued that the 11 states had never left. The Constitution forbade secession, and so the Union had never been dissolved. As a consequence, to his way of thinking, these southern states should resume their place, their former rights and privileges restored, as soon as their governments could be deemed loyal. That would happen if they renounced secession, accepted slavery’s abolition, and swore allegiance to the federal government. In theory, such a speedy restoration would swiftly repair the wounds of war.

Yet what about the condition of four million black men and women, recently freed but who had been deprived during their lives of literacy, legitimacy, and selfhood? Shouldn’t this newly free people be able to control their education, their employment, and their representation in government? Were these black men and women then citizens, and if so, could the men then vote? In 1865, just after the war ended, the white delegates to the South Carolina state convention would hear none of that. As journalist Sidney Andrews reported in disgust, to them “the negro is an animal; a higher sort of animal, to be sure, than the dog or the horse.”

Would the nation then reinstate the supremacist status quo for whites? “Can we,” a Union general was asked, “depend on our President to exert his influence to keep out the Southern States till they secure to the blacks at least the freedom they now have on paper?” Allowing white southerners to rejoin the Union quickly while at the same time denying the black man the vote seemed to many Republicans, black and white, “replanting the seeds of rebellion,” as Stevens said, “which, within the next quarter of a century will germinate and produce the same bloody strife which has just ended.”

In a South where houses had been burned, crops had failed, and the railroads had been destroyed, soldiers were hobbling home from the front in gray rags, seeking paroles, jobs, and government office. Thousands of people, both black and white, were dying of starvation. Around Savannah, about 2,000 people had to live on charity. Black men and women in the hundreds had been turned off plantations with little or no money and maybe a bushel of corn.

Visitors from the North frequently found white southerners smoldering, aggrieved, and intransigent; white southerners had tried to protect their homes, believing they had fought for the unassailable right of each state to make its own laws and preserve its own customs. Having lost the war, they would not surrender such rights easily. “It is our duty,” said South Carolina planter Wade Hampton, “to support the President of the United States so long as he manifests a disposition to restore all our rights as a sovereign State.” Union General Philip Sheridan, renowned for his unrelenting aggression during the war, alerted his superiors that planters in Texas were secretly conspiring “against [the] rights” of the freedmen. In New Orleans, the journalist Whitelaw Reid, traveling through the South, was stunned to find a picture of Lincoln hanging next to one of John Wilkes Booth, and above them both a huge portrait of Robert E. Lee.

All through the South, ex-Confederates vilified the black population, and one legislature after another passed “black codes,” ordinances designed to prevent freed men and women from owning property, traveling freely, making contracts, and enjoying any form of civil rights or due process. “People had not got over regarding negroes as something other than men,” wrote Reid. Meanwhile, Andrew Johnson, the Tennessean occupying the White House, had acted quickly. While Congress was in recess, he singlehandedly reestablished southern state governments by executive proclamation. He subsequently issued pardons to former Confederates on easy terms and at an astonishing rate. Later, he nudged out of the Freedmen’s Bureau those who disagreed with his position and tried to shut down the bureau by vetoing legislation that would keep it running. He vetoed civil rights legislation as unfair to whites and attempted to block passage of the Fourteenth Amendment, which guaranteed citizenship to blacks. He turned a cold eye on the violence directed toward the freedmen, and he emphatically staked out a position he sought to maintain, saying, “Everyone would and must admit that the white race is superior to the black.”

On December 4, 1865, at the opening session of the 39th Congress, the clerk of the House had omitted from the roll call the names of southern congressmen. Battle lines were being drawn, albeit without a rifle or a bayonet.

The four-year period between the death of Lincoln in the spring of 1865 and the inauguration of Grant seems a thicket of competing convictions, festering suspicions, and bold prejudices. Yet oddly, this intensely dramatic event—the impeachment of the U.S. president—has been largely papered over or ignored. Historians have often sidestepped that ignominious moment when a highly unlikable President Johnson was brought to trial in the Senate, presumably by fanatical foes. The whole episode left such a bitter aftertaste that, as the eminent scholar C. Vann Woodward wrote in 1974, historians often relegated the term “impeachment” to the “abysmal dustbin” of never-again experiences—like “secession,” “appeasement,” and “isolationism.”

The year before Woodward’s pronouncement, though, the historian Michael Les Benedict had brilliantly scrutinized the political dimensions of Johnson’s impeachment, thus breaking with the long tradition of embarrassment, outrage, or silence. Regardless, that tradition has persisted—despite David O. Stewart’s careful study, a decade ago, of how dark money may have influenced the final Senate vote. And although Stewart, a practiced lawyer, was not sympathetic to Andrew Johnson, he too concluded, albeit sadly, that the whole affair was a “political and legal train wreck.”

But to reduce the impeachment of President Johnson to a mistaken incident in American history, a bad taste in the mouth, disagreeable and embarrassing, is to forget the extent to which slavery and thus the very fate of the nation lay behind Johnson’s impeachment. “This is one of the last great battles with Slavery,” Sen. Sumner said. “Driven from these legislative chambers, driven from the field of war, this monstrous power has found refuge in the Executive Mansion, where, in utter disregard of the Constitution and law, it seeks to exercise its ancient domineering sway.”

Impeachment: it was neither trivial nor ignominious. It was unmistakably about race. It was about racial prejudice, which is not trivial but shameful. That may be a reason why impeachment and what lay behind it were frequently swept under the national carpet. Then too the whole idea of impeachment does not fit comfortably within the national myth of a democratic country founded in liberty, with abundant space, opportunity, and resources available to all. Impeaching a president implies that we make mistakes, grave ones, in electing or appointing officials. It suggests that these elected men and women might be not great but small, unable to listen to, never mind to represent, the people they serve, much less to serve them with justice, conscience, and equanimity. Impeachment suggests dysfunction, uncertainty, and discord—not the discord of war, which can be memorialized as valorous, purposeful, and idealistic, but the far less dramatic and often sad, squalid, intemperate conflicts of peace: partisanship, rancor, and racial division. Impeachment implies a failure—a failure of government of the people to function, and of leaders to lead. Presidential impeachment means failure at the very top.

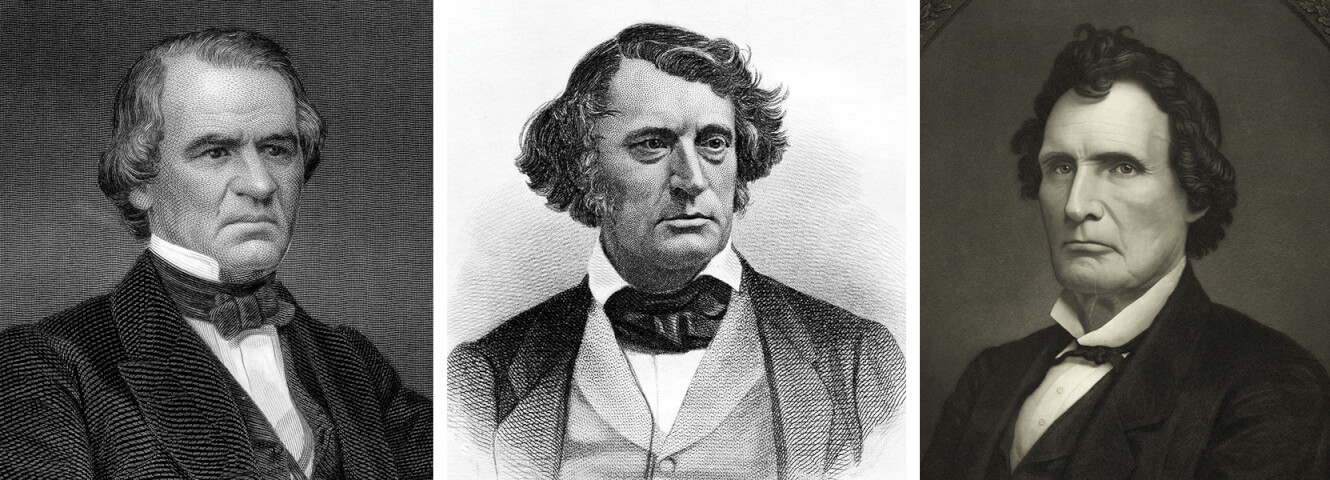

In 1868, President Johnson was impeached and then brought to trial in the Senate by men who could no longer tolerate his arrogance and bigotry, his apparent abuse of power, and finally, his violation of the law. Johnson’s impeachment was thus not a plot hatched by a couple of rabid partisans—notably Stevens of the House and Sumner of the Senate. Both Stevens and Sumner were unswerving champions of abolition and civil rights—and yet both were long considered to be malicious and vindictive zealots, cold and maniacal men incapable of compassion or mercy.

The president and his principal accusers: Did Sen. Sumner and Rep. Stevens act out of partisan rancor or a commitment to racial equality? (Left to right: iStock (2); Library of Congress)

Sumner, the regal advocate of human dignity and political equality, more or less came into his own thanks to historian David Herbert Donald’s two biographies of him: one earned a Pulitzer Prize in 1961; the other bore in its title “The Rights of Man.” As for Stevens, John F. Kennedy, in Profiles in Courage, called him “the crippled, fanatical personification of the extremes of the Radical Republican movement, master of the House of Representatives, with a mouth like the thin edge of an ax.” Kennedy’s depiction of Stevens in his 1956 book was derived in part from the diabolical portrayal of the congressman in D. W. Griffith’s controversial 1915 movie, Birth of a Nation. In 2012, in the film Lincoln, Steven Spielberg mercifully updated the record, with the actor Tommy Lee Jones playing a more likable version of him. But Stevens still lurks in the shadows of history, a fiendish figure whose clubfoot was said to be a sign of the devil, and a man vengefully bent on destroying the South.

Kennedy also applauded the “courage” of the senators who voted against the conviction of Andrew Johnson, ostensibly because they put the best interests of the country above career and politics. Singling out Edmund G. Ross of Kansas, Kennedy soft-pedaled the fact that Ross may have been bribed to acquit Johnson—or if he wasn’t exactly bribed, he successfully importuned Johnson for favors, perks, and position shortly after his apparently courageous vote.

Then there is President Johnson. Lambasted as “King Andy” in one of Thomas Nast’s biting political cartoons, Johnson was a self-made man, born in a log cabin and raised in poverty, who rose after Lincoln’s assassination to the topmost position in the land. In his youth, he had been a tailor with a taste for stump oratory and politics, and in 1829, at the age of 21, he was elected alderman in Greeneville, Tennessee, where he was living with his wife and child. He then became mayor, then legislator, then state senator, and he was subsequently elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. He served in Congress for 10 years before being elected governor of Tennessee, and he eventually landed in the U.S. Senate as a fierce states’-rights Democrat but also a staunch Unionist.

Johnson’s heroic, lonely stand against secession—he was the only senator from a Confederate state to oppose it—earned him an appointment as military governor of Tennessee during the war and then the vice-presidential slot when President Lincoln ran for reelection in 1864.

With a southern War Democrat on the Republican ticket, Peace Democrats could not easily tag Lincoln as anti-South. Johnson also helped Lincoln appeal to the working class, especially to the Irish, for Johnson did not approve of the common prejudice against Catholics. Yet his tenure as vice president began badly. Presumably suffering from a nasty cold, he had medicated himself with a concoction that included some fortifying shots of alcohol, and arrived at Lincoln’s second inauguration reeking of whiskey. After muttering something not quite comprehensible about his being a plebeian and a man of the people, he bent over and planted a sloppy kiss on the Bible. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles shifted uncomfortably in his seat and said to Secretary of War Stanton, who would play an important role in the impeachment, that Johnson must be either drunk or crazy.

Regardless, after the dust of impeachment had mostly settled, Johnson was credited as being the valiant public servant whose plan for Reconstruction had been temperate, fair minded, constitutional, and intrepid. One biographer in the 1920s, anticipating Kennedy’s portrayal, christened Johnson a “profile in courage” whom future generations would regard as an “unscathed cross upon a smoking battlefield.” Johnson was seen for a time as a populist, a champion of democracy and of the beloved Constitution, a man of principle, flawed perhaps, but honest, upright, brave.

Perhaps he had been brave—if, that is, one can separate mettle from mulishness. For in the end, Johnson assumed powers as president that he used to thwart the laws he didn’t like. He disregarded Congress, whose legitimacy he ignored. He sought to restore the South as the province of white men and to return to power a planter class that perpetuated racial distrust and violence.

Still, he had once vowed to penalize the traitorous, secessionist South. “The American people must be taught—if they do not already feel—that treason is a crime and must be punished,” he had said just days after Lincoln’s assassination. At the same time, he argued, as he always had, that since secession was illegal, only people could be traitors, not states. His position was that as long as rebels applied to him for pardons, which they amply did, he would amply grant them. A traitor, to Johnson, then became anyone he disliked—mostly Republicans, and especially men like Stevens and Sumner.

Convinced by the summer of 1866 that congressional Republicans were out to get him, Johnson toured the North and West, and in a set of speeches remarkable for their vituperation, he shouted out to the crowds that he hadn’t been responsible for recent riots, such as had occurred in Memphis and New Orleans. Blame Charles Sumner, blame Thad Stevens, blame Congress or anyone dubious of the southern governments he had put in place, crackpot fanatics who wanted to give all people the vote, even in some cases women, regardless of color. Don’t blame him.

The years right after the war were years of blood and iron: bloody streets, iron men, oaths of allegiance, as they were called, in which former rebels swore their loyalty to the Union. But to what kind of Union government were they promising to be loyal? For these were years in which the executive and the legislature struggled to define, or redefine, the responsibilities of a representative government—and the question of who would be fairly represented. These were nightmare years of sound and fury, fanaticism and terror, of political idealism and mixed motives, of double-dealing and high principle—of racism, confusion, and fear. It was a time of opportunism, paranoia, pluck, and tragedy: tragedy for the nation, to be sure, and for individuals, often nameless, who lost their lives in the very, very troubled attempts to remake the country and to make it whole.

The nation was at a crossroads, and at the very center of that crossroads was impeachment.

Brenda Wineapple’s The Impeachers: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the Dream of a Just Nation, from which this article is excerpted, will be published in May.