During and after the final year of World War I, some 50 million people worldwide died from the deadliest influenza pandemic in history. Called the Spanish Flu, on the mistaken belief that it had originated in Spain, it actually surfaced in rural Haskell County, Kansas. People there were familiar with the flu that emerged every winter and was symptomatically similar to the common cold. But something was different about the flu that sickened the Kansas farmers and others in January 1918. There were the usual symptoms: coughs, muscle aches, and fevers, but among new symptoms were very severe headaches. One local doctor noted that this flu was striking mostly healthy young adults, rather than children and old-timers—and it often led to fatal cases of pneumonia.

The outbreak in sparsely populated Haskell County soon trailed off, and appeared to be over. Instead, this was just the initial appearance of a novel avian virus that soon exploded from Kansas across America to Europe and then swept around the world in three distinct waves in the next 12 months, killing millions on every continent but Antarctica.

The victims never knew what hit them, because in 1918 no one knew very much about what a virus was, where it came from, what it could do, or how to treat it, let alone how to stop it. And because it was a novel strain, no person anywhere was immune to it. What was known: it was wildly contagious and evidently spread via close social contact.

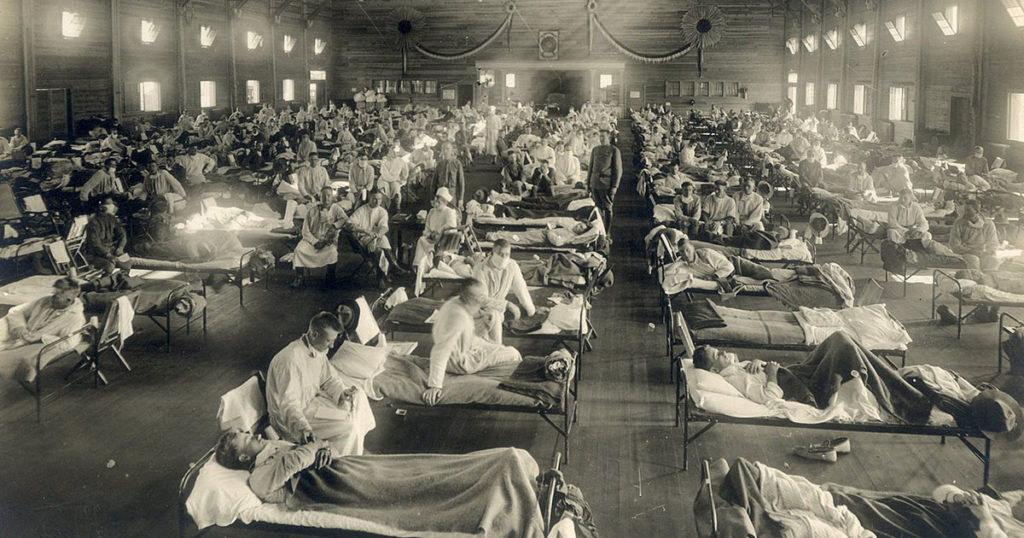

Some young men from Haskell County, already exposed to the flu, had joined the Army and been assigned to a new Kansas training cantonment, Camp Funston, the largest such camp in the United States. It was jammed with some 56,000 army trainees. One of them from Haskell County reported to the base hospital with a bad headache. Within hours, more than 100 other trainees checked in with acute flu symptoms, and the numbers grew every day.

The fast-expanding U.S. Army was on the move in 1918, preparing to join the Allies in the large-scale combat of World War I. Soldiers were traveling en masse to other training camps across the United States and to East Coast ports for shipping out to France. In their book, Three Seconds Until Midnight, Steven Hatfill, Robert Coullahan, and John Walsh, Jr. describe what happened next: “By the end of March, some 24 of the largest 36 military training camps in the United States were experiencing influenza outbreaks,” as were about 30 cities located close to the camps.

In the spring and early summer of 1918, World War I entered a critical phase. The beleaguered German army had gathered all its available troops for one desperate attack on the Western Front, the so-called Ludendorff Offensive, and the Allies were in equally desperate need of manpower to blunt the German advance. American troopships, many of them overcrowded and unsanitary, rushed thousands of young soldiers to France, and the influenza virus rode along with them. It spread quickly to the British and French armies, with many thousands of cases breaking out. It spread to civilian populations in France and England, to the German army, and by midsummer appeared in much of Europe, and continued to spread via ocean shipping to Africa and Asia.

Curiously, this first wave of the pandemic became less lethal as it spread. Hundreds of thousands sickened, but only a small percentage died. That was about to change.

During the summer, scattered reports emerged about new cases that were far deadlier than most earlier cases. In French and English cities, patients appeared with major lung damage, many of them going from first symptoms to death in just a few days.

This second wave of the influenza pandemic circled back to the United States in late June, with the arrival of a British freighter in Philadelphia. Crew members had fallen ill during their Atlantic crossing. Upon docking, they were quarantined, many with severe pneumonia, and about a quarter of them died. Then, in August, when many new cases broke out in the Philadelphia Navy Yard, Wilmer Krusen, the city’s director of public health, thinking the city was facing an ordinary seasonal flu, said “citizens had nothing to fear so long as influenza cases were strictly isolated.” The next day he learned that the Naval Hospital had received 400 new cases. Still, public-health officials and political leaders failed to grasp the magnitude of the threat.

That failure was highlighted by a tragic decision: Philadelphia’s civic leaders decided to go ahead on September 28 with a downtown event, the Fourth Liberty Loan Parade, before a crowd of some 200,000 people. The predictable result of this misjudgment was summed up in the University of Michigan’s The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919: A Digital Encyclopedia (2016): “Within a few days of the parade, Philadelphia was rocked by a massive spike in the number of influenza cases. Hospital beds quickly filled, and the city’s physicians and nurses were overwhelmed by the surge.”

While city officials hesitated to take action, Pennsylvania Health Commissioner Dr. Franklin B. Royer on October 3 issued a mandatory statewide closure order for, as the digital encyclopedia summarizes, “all places of public amusement, including theaters, poolrooms, dance halls, and salons. Saloons, hotel and club bars and cafés were also closed. Closure of schools and churches was left to local authorities.” It proved to be an exemplary move, and the city’s board of health promptly closed all public and private schools and all places of worship. Four days later, the new influenza cases in Philadelphia exceeded 5,500. The city paid a big price for its early inaction, suffering one of the worst death rates among American cities.

This second wave of the mutated influenza also broke in Boston with the arrival of a troopship returning soldiers––some already infected–– from France in late August. They were housed in a barracks near the harbor to await assignment to other military facilities. But almost immediately, nearly 60 cases broke out among those soldiers, and the rapid expansion of this deadly strain of the influenza in the Boston area had begun.

One of the hardest-hit places, northwest of Boston, was a large U.S. Army cantonment, Camp Devens. In the early days of September, it was already overcrowded with 45,000 army trainees, and the influenza quickly infected one-fifth of the young soldiers. Devens did have a large hospital, but it was soon overwhelmed, even as scores of military doctors and nurses were ordered to converge there. Many of them soon grew sick and some died. The survivors, professionally powerless before a violent disease with no cure, could only bear witness to the unprecedented carnage that was killing a hundred young soldiers a day.

Among visitors to the camp was a research team of doctors and other scientists led by William Welch, one of America’s most distinguished physicians. Seeking to understand this rampant disease, they examined and interviewed the sick and dying patients and began performing autopsies. They were stunned at what they found: lungs that were not merely dysfunctional, but were destroyed and all but unrecognizable, plus gross damage to hearts, kidneys, livers, and brains, with uncontrolled bleeding everywhere. This was a horrific form of influenza that no one had ever seen before. It was too late for quarantines; the second wave was already spreading across the country. The surge at Camp Devens was a preview of what would soon appear in American cities from coast to coast during September and October.

Every city had its own distinctive story about coping with the pandemic. Some cities responded with alacrity and swift closures. Others responded poorly. Many began by downplaying the severity of the crisis or even denying its existence, before realizing that they had no vaccines and no pharmaceutical remedies to deal with what was a very real problem. Most hospitals were already operating at capacity, and in many cities there were shortages of trained medical professionals due to wartime service in Europe. Quarantining and what is now called social distancing were the only means to slow the contagion. Gauze masks and closures—from school systems to saloons––were all they had.

In New York City, many ships from Europe arrived in late August and early September with flu-infected sailors and passengers, and the entire port was quarantined on September 12. An aggressive policy of identifying and isolating the infected was implemented, but the case count topped 4,000 by October 4. The city’s many settlement houses and volunteer organizations mounted major efforts to help treat the victims. When the epidemic faded in mid-November, the city had dealt with almost 147,000 cases and nearly 21,000 deaths.

Like other ports near military bases, Baltimore faced a rapid onset in September, with more than 300 cases at Fort McHenry and more than 1,000 at the Aberdeen Proving Ground. The city’s health commissioner, John D. Blake, believed it was just “the same old influenza,” and that closures “would do more harm than good.” But as the case count mounted, the school board unilaterally ordered all schools shut. Other closures followed, but soon, both hospitals and cemeteries were swamped. Through it all, the city’s racial divide remained intact, as all but two hospitals admitted only whites or only African Americans, and white city employees refused to dig graves for blacks. In response, the War Department assigned 342 African-American soldiers to dig graves.

In the end, 24,000 cases of influenza resulted in 4,100 fatalities.

St. Louis, unlike many other U.S. cities, acted quickly and decisively. Its energetic health commissioner, Max C. Starkloff, began monitoring the advance of the pandemic in eastern cities and, before the city had a single victim, asked physicians to report any and all suspected cases. He encouraged the mayor to declare a pubic-health emergency. In early October, the mayor and community leaders agreed to a sweeping closure order. Community volunteers including teachers, policemen, Red Cross drivers, and others from civic organizations provided many services. Closures were lifted only gradually as new cases declined. St. Louis emerged from the pandemic with one of the lowest death rates among American cities.

Pittsburgh officials were initially skeptical of news about the city’s first influenza case on October 1, while Pennsylvania’s acting commissioner of health, Benjamin Franklin Royer––alarmed by Philadelphia’s 635 new cases on that same day––initiated dramatic efforts to contain the disease. Royer’s statewide closure order for establishments and activities ranging from saloons to funerals was viewed by Pittsburgh mayor Edward Babcock as “too drastic.” That attitude changed in a few days, when the city reported 1,300 new cases and he ordered closures, opened temporary hospitals, and undertook aggressive home inspections. The closing of schools was delayed until October 24, and by that time there were 7,500 cases and climbing. Squabbling continued between state and local authorities and business people insisting on reopening. Businesses did reopen on November 9 and schools nine days later. But influenza cases continued into April. The upshot was that Pittsburgh’s epidemic death rate was the worst of any American city––possibly due to the chronic air pollution caused by the city’s steel mills.

After more than 2,000 cases were reported in San Francisco by mid-October, the city responded within days with closure orders and a major push for the wearing of gauze masks. The masks became a symbol of the city’s patriotism and concern, and a legal requirement on October 25—with violators subject to fines and even jail. Nevertheless, by the epidemic’s end in the winter of 1919, some 45,000 cases and 3,000 deaths had befallen the city.

The influenza pandemic of 1918–1919 claimed 675,000 American lives. Perhaps the most astonishing fact about this historic catastrophe is how very nearly its lessons were forgotten in America—and are only now beginning to be relearned.

Much of the factual information in this article is drawn from the Influenza Encyclopedia: The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919, a Digital Encyclopedia, produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library.