On a spring day in 1964, a boy walked into the Oldfield Hotel in the London suburb of Greenford—or perhaps the White Hart Hotel in Acton, or perhaps an unknown pub on London’s North Circular Road; fact slides so easily into myth—and demanded an audition from the band playing there that night.

The boy was 17 years old. He was the drummer for a surf band called the Beachcombers. He hit his drums so hard that six-inch nails had to be driven through the base of his kit into the stage to keep it from wandering off when he played. He had been playing drums for five years. He had first tried the bugle, but then he heard the American jazz drummers Gene Krupa and Philly Jo Jones, and he was enlightened, so he switched to the drums and practiced in a music store with a kindhearted and probably hard-of-hearing owner. At age 14 he quit school altogether and got a job repairing radios. Part of the reason he quit school was that his teachers thought he was a dolt: “Retarded artistically, idiotic in other respects,” wrote his art teacher.

Because of his job, he was able to buy his own drum kit and take lessons from an older drummer, for 10 shillings (about $7) per lesson. He began sneaking into the Oldfield Hotel’s tavern to watch his teacher drumming for a wild band called the Savages, led by a singer called (for good reason) Screaming Lord Sutch. The boy then joined a band called the Escorts. One of the other Escorts called his drumming “outrageous … madness bordering on genius.” He lasted about six months before joining the Beachcombers and becoming obsessed with surf music, though he had never surfed in his life. He listened to the Chantays and Dick Dale and the Beach Boys. He said years later that he would have joined the Beach Boys in a heartbeat, if only they had asked.

He lasted a whole year in the Beachcombers, playing at night, working during the day selling gypsum plasterboard. His father was thrilled he had a steady job, but the boy was not at all thrilled, and he kept going to the Oldfield Hotel at night to listen to other drummers. One of the bands he saw there played 16 times in early 1964. Most of their sets were covers of the American blues and soul music they loved: Willie Dixon, Bo Diddley, Howlin’ Wolf, Wilson Pickett, Chuck Berry; not until late in the year would they feature a song composed by the guitarist, who would end up writing almost all of their songs. The boy might well have seen every one of those 16 shows, as he is not reported to have had any fervid interests at age 17 other than playing drums, and his wages would have paid for admittance and beer.

According to one account, the boy walked into the Oldfield one day that spring, in either April or May, approached the band’s guitarist, cheerfully announced he could play better than the drummer they had, and proceeded to prove it when the guitarist invited him behind the drums. The guitarist, all of 19 himself at the time, remembers that the boy was dressed from head to toe in ginger colors and had dyed his hair ginger and was “a ginger vision.” How easy it would have been, during those first few astoundingly fragile moments, for the guitarist to sneer at the ginger boy’s bold pitch; how easy for the bassist to surrender, moaning, during the first few bars, unnerved by such bizarre drumming; how easy for the singer to shriek in fury as the ginger boy drummed right through an aria. But none of the other band members did those things, and so it was that Keith John Moon, son of Alf and Kit, joined the Who.

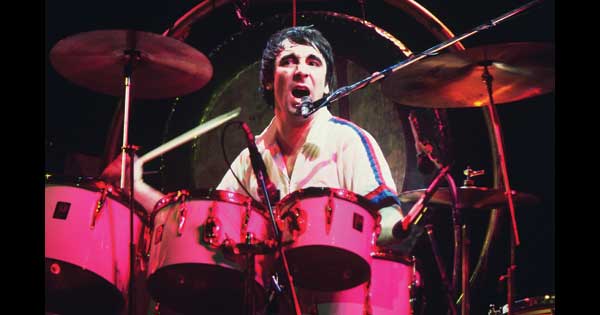

Of the man and the band and their subsequent adventures and misadventures much has been written; but I do not wish to add to that ocean of ink. No: it is those first minutes of his audition that I wish to sing, for once he had leapt up behind the drum kit, laughed maniacally as he took sticks in hand, checked his pedals, and nodded to the bassist to begin, the minutes that followed changed the course of rock music, and changed the way drummers played, and lit a fire under what might have been the greatest live rock band ever, and opened a door in the world for a wild music that has delighted countless people since. For Moon, I think, was the first rock drummer to perform not merely as a timekeeper, a rhythm anchor, a companion to the bass, the two instruments joined as foundations for the free play of guitarists and sax players and piano players and singers; he played the drums as a lead instrument itself, riffing not off the steady metronome of the bass but off the sprint and soar of the lead guitar. And because he was entranced by the spontaneity of jazz, he played freely, filling in runs wherever he pleased, playing fast or slow as the mood took him, essentially making his bandmates follow him.

We are so used to the character and composition of great bands that we forget sometimes that they were born by happy accident, and their later accomplishments hung by the merest thread of happenstance: Keith Richards noticing the blues records under Mick Jagger’s arm at a train station in Kent, John Lennon meeting Paul McCartney in a church hall in Liverpool, Clarence Clemons walking into a beach bar in New Jersey and meeting Bruce Springsteen, 15-year-old drummer Larry Mullen Jr. pinning a notice on the bulletin board of his Dublin high school looking for other kids who liked to play music.

And a boy all dressed in ginger, with his hair dyed ginger. He would go on to be a legend, in ways both sad and joyous: a roaring drunk, a manic and perhaps deeply lonely man, an utterly idiosyncratic genius on his instrument in his prime, a gifted wit and comic, and dead so young, too young, not yet 33 years old. But there was a moment there, in a hotel tavern one spring day, when the boy who could fix radios, who adored surf music, who practiced alone in a music shop, screwed up his courage and shouted cheerfully up at a young Pete Townshend; and everything was different ever after.