One of the best parts of living in France is the country’s proximity to Italy. From Paris, you can have cacio e pepi in Rome or try on a shirt in Florence for about what it would cost to board an Acela from Manhattan to Boston. I’ve taken advantage of this closeness at least once for each of the past five years. Though the country is famous for the cultural differences among its regions, in certain respects, it really doesn’t matter where you go in Italy: there are uniform standards of quality and taste that obtain nationwide. The same could be said for France or many other places, but unique to Italy is the extent to which these standards are assumed to be necessary, taken for granted even, but never fussed over or made precious. What I mean is that a perfect cup of coffee or an impeccable haircut in Italy, unlike in Paris or New York or Berlin, is not at all the provenance of hipsters.

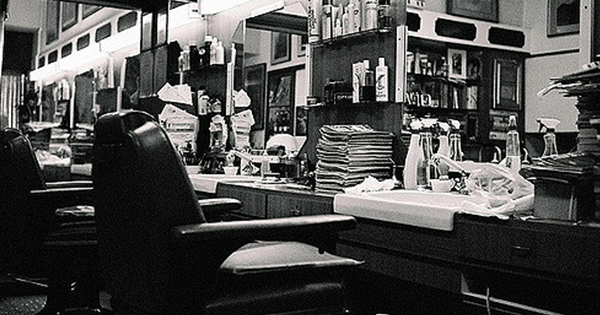

I have never had a better haircut and shave than I got a few weeks ago at Boellis in Naples, with the lather and the straightedge and the choreographed relay of hot and cold towels. (The second best “barba e caruso” of my life was a year prior at a random spot in Rome, behind the Vatican; after it was over, the barber retreated to a wooden desk and wrote out my bill in beautiful penmanship on a piece of paper.) At Boellis, they have been cutting hair this way since Antonio Boellis arrived in Naples from Apulia in 1924 and hung his own shingle. His grandson, wearing a white jacket and necktie, as all of the men in that salon do, was the one who shaved me.

I think of Boellis every time I pass the fancy new barbershop that just opened around the corner from my Paris apartment (where a “rasage à l’ancienne” will set you back about $35.00). The bearded, tattooed proprietors there are roleplaying, acting out a fantasy of what a place like Boellis is naturally. It is this aspect of performance that is so unsettling about so much of modern urban life, no matter how pleasant the game may be. It’s become cliché to marvel at the reach and scale of today’s global monoculture. In almost any Western city (and a great many non-Western ones) and deep into the suburbs, you can find a high-quality iteration of virtually anything you want, providing you’re willing to pay for it. This even means that the small New Jersey town I grew up in during the ’80s and ’90s—a place where good coffee was Dunkin Donuts, pasta was spaghetti, and nonwhite breads were slapped with outrageously generic labels, like “Italian” and “French”—has for years now boasted a wine shop that not only rivals but surpasses most wine stores here in Paris.

And that must be progress. But it comes at a price. Whatever we’ve gained in quality and variety, we have paid through the roof for in naturalness and maturity—a lack of self-consciousness, you might say. What is frequently so refreshing in Italy is the marriage of quality and authenticity. Perhaps this is because Italians have decided to attempt to do fewer things. You’ll be hard pressed to find sushi or even a decent cup of tea in many places. But you can have—at a gas station!—the kind of espresso that would gentrify a Brooklyn neighborhood, or the perfect haircut and shave, and the endeavor hasn’t become a trend or a life style. It’s just the way things are done.