Words fail to convey the magnitude of the Grand Canyon—that abyss almost a mile in depth that stretches to the horizon in three directions, containing a world of side canyons, peaks, and cliffs of all colors, usually washed with the moving shadows of clouds. To get a sense of the place, you have to see it for yourself—and in 2017, 6.3 million people did. Most of them took a quick look and got back into their cars. Fewer than 100,000 people scored a permit from the National Park Service allowing them to sleep in the backcountry, and about 29,000 were authorized to float through the middle of the canyon on the Colorado River. The most common means of doing so is to buy a seat on a 30-foot motorized raft run by a professional guide, who also supervises the “swampers” who do the cooking, cleaning, and worrying for you.

But there is another way.

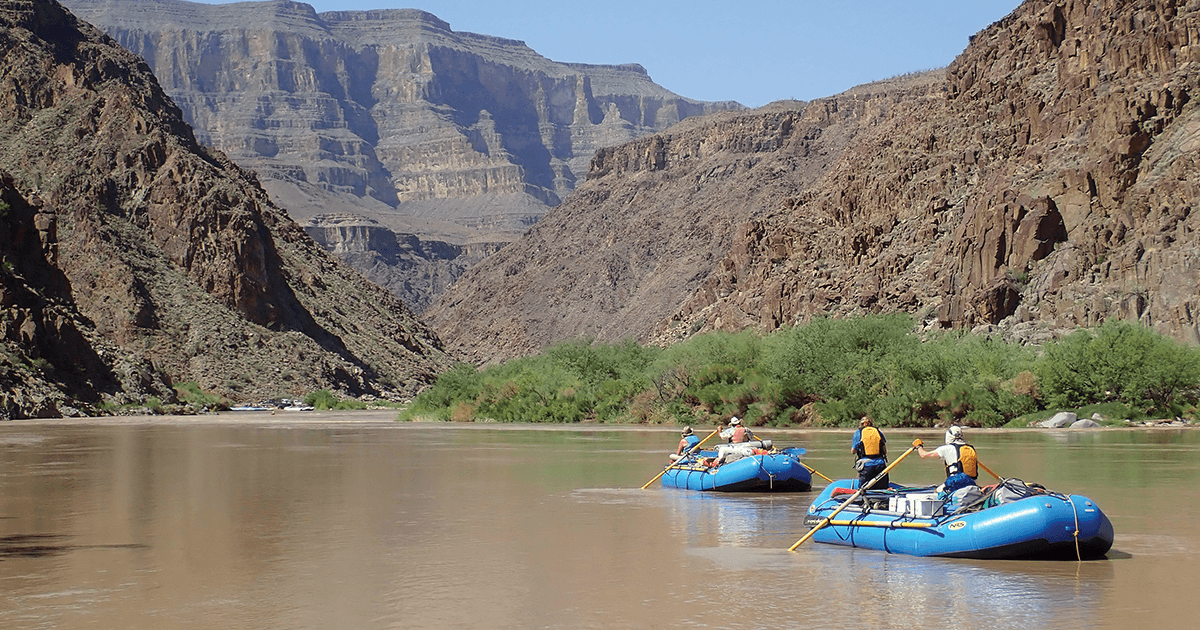

Twice, in 2014 and again last summer, I’ve gone on private, oar-powered rafting trips, in which passengers provide the muscle and manage the risks themselves, without paid help. In 2018, I was also the permit holder with overall responsibility for organizing the trip. Our three rafts were each 18 feet long and well over 1,000 pounds when loaded. Rowing them made for slow, quiet progress at the mercy of the currents. Along the way, we had plenty of time to admire the cliffs from below and anticipate the rapids that lay ahead, our emotions cycling from awe to fear to exhilaration.

More than 1.1 million acres around the Colorado River, not including several million adjoining acres that are also extremely remote, meet the federal definition of wilderness. The river, though, is anything but. In fact, it may be the world’s most heavily regulated running water. Famous for its beauty and power, it is also the canal that connects Glen Canyon Dam to Hoover Dam. Roderick Nash, author of the classic Wilderness and the American Mind (and a former river guide), likens the Grand Canyon to a municipal tennis court where people must make appointments and take turns to keep it from being overrun.

Although the canyon is renowned for its whitewater, which stars in thousands of Internet videos showing screaming people plunging through enormous waves, an equally harrowing obstacle is the law of supply and demand. The full 16-day, 226-mile trip from Lees Ferry to Diamond Creek, Arizona, costs about $4,500 per person with hired help. A private, noncommercial trip can cost half that much, but first you need a permit, and you can’t get one until you win a drawing.

Every February, the National Park Service holds a lottery that awards private permits to parties of up to eight or 16. Applicants can ask for as many as five different launch dates; winners get one of their choices, and changes are not allowed. The odds of getting a permit to launch during the peak season, May 1 to August 31, can be several hundred to one. If you’re fortunate enough to win, NPS requires that you follow 35 pages of strict regulations on such activities as cooking, eating, sleeping, and maintaining sanitary standards. They are essential to preserving human health and biodiversity at a small number of heavily used campsites and trails. They also help maintain the myth that the river is still wild.

The rules seem to work. No one got a stomach bug on either of my trips, the campsites were clean, the plants were healthy, and the animals seemed untamed, except for the ravens. We faced a constant risk that one would swoop into our camp, pick up something shiny or tasty, and fly away with it. Camps have lost half-empty cans of beer, bags of chips, and even digital cameras to these hardened criminals, who mate for life and work in pairs. Every morning as we broke camp, two ravens would alight nearby. As soon as we pushed off, they always landed exactly where the kitchen had been, policing the site even more closely than we had.

Although much of the Colorado River is deceptively flat and peaceful, beneath its surface, strong currents are constantly acting on the rafts. (Courtesy of the author)

After my first trip, I was so eager to do it again that I plunged into the NPS permit system. I was lucky: I won an eight-seat permit in February 2017, with a launch date in late July 2018. I immediately called Doc Swampy, a.k.a. Rod Metcalf, a geology professor at UNLV who presides over faculty meetings and presents papers at international conferences. Doc, his alter ego, is a good ol’ boy from Paducah, Kentucky, who loves to put on a beat-up straw cowboy hat, drink beer, and tell jokes. He has done the trip 19 times, both privately and as a professional guide, and like me, he has a constant yearning to go back.

Doc had been the lead boatman on my 2014 trip, and at the bottom of one scary rapid I rowed, he looked over at me, soaking and shaky, and said, “You did fine. A chimp could do this!” I needed to borrow some of that confidence as my wife, Tania, and I spent hundreds of hours choosing companions with experience on the river, hiring an outfitter, meeting various NPS requirements, making travel arrangements, planning the menu, reviewing gear, and losing sleep over all the facets of this expedition.

When the eight of us finally got to the launch site at Lees Ferry (Mile 0 on the maps), it was 102 degrees, with low humidity and a light wind. We felt like we were inside a food dehydrator. Spreading out everything we needed on the beach, we spent the afternoon inflating our rafts, fitting them with steel frames, and attaching 12-foot oars—two sets per boat, in case one broke. Then we loaded the rafts with huge, superinsulated coolers packed to the brim, waterproof food cans, watertight bags stuffed with personal gear, a mobile kitchen and bathroom, an array of safety equipment that had been inspected by an NPS ranger, and what seemed to me an unreasonable amount of beer.

We pushed off around 11 A.M. on July 24 and headed downriver, with our selves, our sustenance, and our security contained within three neoprene rings. We wore long pants and sleeves to ward off sunburn. When we got too hot, we’d fall backward into the river and go back to work dripping. Ten minutes later, we were dry again. After a few days of this, our clothes and skin resembled crinkled paper. The first thing we did every morning was smear any exposed skin with high-test sunscreen. The last thing we did at night was coat our battered hands and feet with an extra-strength lotion formulated to moisturize cracked horse hooves.

With all due respect to Roderick Nash, river rowers aren’t exactly like tennis players. We are willing to accept significant risks and discomfort to play our game. The only store along the river is the Phantom Ranch Canteen at Mile 88, which warns that “goods and services are minimal.” There are no road crossings, and the only way in or out is a long, dry hike or a ride on a rescue helicopter. But like tennis players, we do insist on eating well and having cocktails before dinner.

On the evening of Day 3, over margaritas and beneath a jaw-dropping sunset, I asked Doc why, earlier that day, he had stood up in his raft, turned toward river right, and held his cowboy hat over his heart. He told me about Bert Loper, who was born in 1869 on the same day that explorer John Wesley Powell reached the confluence of the Colorado and San Juan rivers. Loper was lead boatman of the 1920 expedition that determined the future site of the Hoover Dam. He died of a heart attack at age 79 while running the rapid at Mile 24.5. His crewmates couldn’t find the body, but they recovered his handmade boat and dragged it up to a small knoll at Mile 41.6, where the lumber remains today. Bert’s skull showed up 26 years later.

Doc also introduced me to Buzz Holmstrom, a small-town auto mechanic who escaped the grimness of the Great Depression by reading everything he could find about western rivers. Buzz shocked the tiny community of river runners in 1937 by rowing the Green and Colorado rivers alone. Advance research, careful observation, and intuition made him a genius at the skill guides call “reading the river.”

Near the end of his solo trip, just after a passage in his journal in which he explains how to shape biscuit dough by peeling it off a boat plank, Holmstrom writes,

I had thot—once past [the last rapid]—my reward will begin—but now—everything ahead seems kind of empty & I find I have already had my reward—in the doing of the thing—the stars & cliffs & canyons—the roar of the rapids—the moon—the uncertainty—worry—the relief when thru each one—the campfires at nite—the real respect & friendship of the rivermen I met & others

Lonesome cowboy musings like these are irresistible to those of us who have been bitten by the river bug. Buzz’s journal invites us into a mind that deciphers rapids the way we do, only better. We end our evenings on the river just as he did, marveling at the stars and lulled by the sound of running water.

I value Bert and Buzz as much as Doc does, but I was also grateful for our satellite phone, maps, guidebooks, and regular visits from other expeditions. I wanted maximum exposure to the canyon with minimum risk, and that meant spending lots of time on safety and sanitation. We purified one gallon of river water per person per day and followed detailed protocols for food preparation and cleanup. The NPS instructed us to pour our urine and strained dishwater directly into the river. Our feces went into a plastic jug inside a steel ammunition can called a groover. The name comes from the old days when the can did not have a seat, so it would leave marks on your behind. Every morning, we’d load the groover back onto a raft that we dubbed the poop boat.

The routine didn’t leave much time for wilderness hikes, so in our planning Tania and I had insisted that we include one layover day. On Day 5, we left our rafts at Kwagunt Creek (Mile 56), where the river elevation is about 2,800 feet, and started up the canyon. Our goal was to hike about four miles to Butte Fault and return to the camp’s shade before the worst of the midday heat.

We got to the head of the canyon around 10 A.M. and looked up to Butte Fault, which runs parallel to the river, through a valley that seemed entirely free of shade and water. I could squint and see the branches on the ponderosa pines up on the North Rim. Getting there would mean going another eight miles on barely used trails, with perhaps another 6,000 feet of elevation gain. I was tempted to try it, but, fortunately, Tania did not lose her mind. She went back down to Kwagunt Creek and lay down in the middle of its clean water fully clothed, stretched out like a salamander with an ecstatic smile on her face.

Despite the heat, hypothermia is a serious concern. The river water is released from the base of Glen Canyon Dam and has a constant temperature of around 50 degrees, even in summer. People quickly lose strength in water that cold, so no one is allowed to go in, on, or even near the river without putting on a whitewater-grade life preserver that has an attached whistle (in case you can’t be seen) and a knife (in case you get tangled in a line underwater). Drownings are not uncommon in the Grand Canyon, but the victims are almost always drunk, not wearing a life vest, or both. Still, even perfectly sober people feel like heroes when they get to the bottom of the big waves right-side up.

After a few soakings, I started to see the rapids for what they really are: beautiful displays of fluid dynamics. They are caused by flash floods in side canyons that dam the main channel with rocks and mud, resulting in a pool-and-drop pattern. In the first stage (the pool), the raft floats through water that is unusually still, the river gradually getting shallower and faster as it approaches the obstruction. Waves form just above the shallowest, narrowest point of the rapid, and a smooth tongue of water starts the drop. The tongue gets narrower until it is submerged by the waves, which increase in size and complexity depending on the volume of water, the steepness of the drop, and whatever obstacles are in the way of the superturbulent jet that flows past them. Reading the river means figuring out the effect these forces will have on your boat.

Mile 56, Kwagnut Creek, elevation 2,800 feet: Tania “stretched out like a salamander,” forgoing a hike to Butte Fault, which runs parallel to the river. (Courtesy of the author)

At Mile 77, we spent a long time considering our options before running Hance Rapid, which is legendary for flipping boats and cracking skulls. But really, there wasn’t much we could do apart from strapping on our helmets. Rowers can control only their angle of entry and the speed at which they enter a rapid. It’s a bit like lining up a billiards shot. A strong rower might be able to turn a raft once and bend its trajectory slightly in the 20 to 30 seconds it takes to go through a big rapid, but most of what happens is up to the river. Joan Fryxell, who was my raft mate and rowing coach, gave the most helpful advice as we stood on an outcrop and studied the 12-foot standing waves: “See that rock? Don’t hit it.”

If you do hit a big rock, it will often flip the raft. On the day I rowed Hance Rapid, the river was flowing at about 9,000 cubic feet (or 280 tons) per second. Larry Stevens, a river guide and ecologist at the Museum of Northern Arizona, explained how much power that is in terms of elephants. At five tons per elephant, that meant about 56 elephants’ worth of water was charging by my raft every second. Near the bottom of Hance are several big rocks, each one blocking perhaps one-third of the river channel. If I had hit one of those rocks and slid into the big hole and wave on the other side of it, the result would be like 18 elephants jumping onto my raft every second. So I was careful to follow Joan’s advice.

Your chances of getting through the rapid without swimming increase if you agree on a plan in advance, hit your marks, and keep rowing. In my case, that was rarely how it went. I didn’t flip my raft but came close at Lava Falls (Mile 180), when I entered the tongue a few feet too far to the right. Everyone assured me that this was not my fault. “There are three kinds of rowers,” said Doc. “Those who have flipped, those who will flip, and those who will flip again.” This is why every expedition carries lines and pulleys to turn rafts back over and drag them off of rocks, and why everything on a raft must be securely tied down.

Most of the river is deceptively calm and flat, but no less of a challenge to navigate. The water is always turbulent, even when the surface is smooth, and an eddy can grab a raft and drag it back upstream if a rower misses the signs. I wore myself out extracting my raft from these slow-motion whirlpools because the force of the water dwarfed what I could do with my oars. It’s far easier to stay in the current, which is often invisible on the surface. Finding it means paying close attention to how the water is moving and where the bubbles are going.

Piloting a raft, like driving a car, means staying hyperalert. I was rewarded for constantly scanning the next 50 yards and penalized for daydreaming, yakking, or making assumptions. But after hours of concentrating on the river, I was able to widen my attention to include the rocks and the sky, and after several days I began noticing different scales of time. During our first 10 miles on the river, we had traveled back in time 60 million years, Joan told me, and the rocks would keep getting older as we sliced deeper into the Colorado Plateau. At Mile 78, we saw the Great Unconformity, a billion-year gap in the geologic record, where the underlying rocks are about 1.7 billion years old. Some of the oldest rocks in the Grand Canyon are pinkish granite and look like freshly ground pork. Others are jet-black schist that can heat up to 140 degrees on an August day. These are weird, twisted, hard outcrops, folded and sinuous like the water.

One day in camp, we saw a pink rattlesnake. Its coloring seemed strange until the snake slithered into an outcrop of that pinkish granite and became invisible. The creeks in side canyons were full of tadpoles and tiny frogs, now trapped in the canyon, whose ancestors had arrived during an earlier era. Adaptations like these happen over millennia, as predators stalk prey and the climate changes. Behind it all are the rocks that seem a jumbled mess until you begin to think in geologic time, imagining the forces that make the weather that makes the animals.

Rod explained that the oldest rocks we saw at the Great Unconformity were created about 20 kilometers underground. As they gradually rose, the softer rock layers above them wore away until the old rocks broke the surface. Then they were submerged into a shallow sea about 525 million years ago and covered by layers of the younger sediments that make up most of the Grand Canyon. By the end of the trip, I saw the rocks and the river as part of a single process, and their silent, linked rhythms felt like Earth’s heart beating.

Everyone on the crew was weary when we pulled into Diamond Creek, but no one had flipped a raft or sustained injuries that a few days’ rest would not cure. Luck had a lot to do with this. On Day 12, we had camped at Fern Glen (Mile 168) and hiked up another beautiful canyon to a 60-foot dry waterfall. The day after we pulled out, an intense afternoon thunderstorm and flash flood devastated the site. Four rafters were evacuated by helicopter. It could easily have been us.

Sometimes I think I’d like to row the Grand Canyon every year. But then I remember the incinerating sun and the constant work and grime, the threat of norovirus and scorpions and falling rocks, and the absence of a cell phone signal for 16 days. After one stressful day, one of our crew, Christie Kroll, described the experience as “a death march with hors d’oeuvres.” But then I remember the river and the light on the rocks, and none of that matters. I want to go back.