The Great Detached

As a journalist, Tom Wolfe’s greatest asset was his emotional distance from his subjects

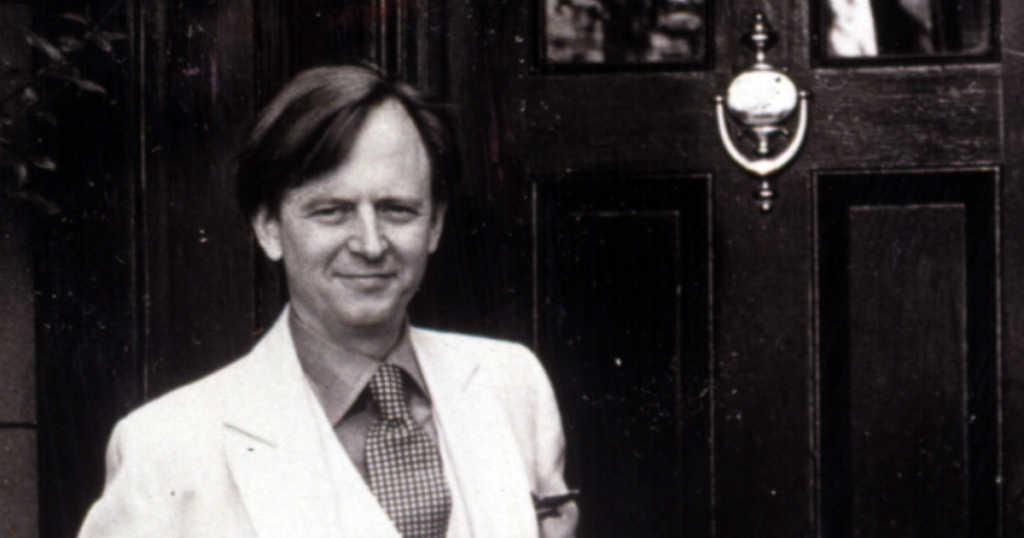

Tom Wolfe died Monday, at age 88, leaving behind a widow, two children, and (one assumes) a grieving Upper East Side dry cleaner. Those white suits—Wolfe wore them even when interviewing dirty hippies—seemed to defy you not to comment on them; they were an offense against taste and, you might erroneously believe, the kind of sartorial fetish favored by someone needy for attention but not deserving of it.

After I read The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Wolfe’s 1968 book about Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, I thought it scandalous that anyone so visibly pretentious could also be such a good writer. It took me years to realize that the suits were integral to the method. They were, he told The Paris Review in 1991, a form of anticamouflage. “There’s no use trying to blend in,” he said. “I might as well be the village information-gatherer, the man from Mars who simply wants to know.”

Leave aside the suggestion that Martians dress like Colonel Sanders. How many times have you read the work of a journalist whose boast, implicit on every page, is that he has gone native with his subjects, that he knows them because he has somehow insinuated himself into their ranks? The most vulgar version of this is insiderism, where the reporter elevates himself until he is one of his subjects—the tenth Supreme Court justice, the sixth Beatle, merely reporting the in-chambers or backstage banter among peers. Such a status is almost never earned—it is a pose.

Wolfe’s preposterous clothing was a constant reminder of a core journalistic truth: to be an observer requires distance, and a writer’s alienation from his subject is not to be annihilated but managed and, most often, treasured. His was a much better pose. There are few worthwhile memoirs of the space program or the High (in at least two senses) Counterculture. But The Right Stuff and The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test are as close to imperishable as journalism ever gets. In both cases, Wolfe examined a scene with a subjectivity and style exclusive to himself. He saw things as Tom Wolfe, with his own gift of studied by playful detachment.

He was the Great Detached. If that phrase sounds like an esoteric Hebrew name for God, then you are not far off: much of what felt new about Wolfe’s style was the way it coopted the omniscient voice. Readers had been trained to think of omniscience as the exsanguinated black-and-white prose to be found on the front of any daily newspaper. But Wolfe appropriated it for himself, bracingly, and supposed that God might use exclamation marks, deploy an arch or mischievous simile, or conceal meanings and themes. And he might do all these things without abandoning the advantage of distance.

No one looks good under the Almighty’s gaze, and many of those who hated Wolfe did so, I think, because he refused to join the team. The Left, in particular, resented his ironic detachment—first in the face of ’60s radicals (Wolfe says he never dropped acid, a sure sign, given the company he kept, that he was at heart a total square), and later that of New York liberals of the 1970s, or as Wolfe called them, the “Radical Chic.” How can anyone but the enemy of a great cause observe its followers and then decline to join their merry band? The affection shown him by conservative intellectual William F. Buckley, Jr. did not help, nor did Wolfe’s tendency to avert his withering, detached retina from Radical Chic’s conservative counterparts.

To tar him for his alleged cryptoconservative politics, though, is to miss the point. In 1983, Christopher Hitchens hissed that Wolfe “[found] the urge for social change to be risible,” on the basis of his account of a famous 1970 society fundraiser that composer Leonard Bernstein threw for the Black Panthers. A friend of mine who was there, and whom Wolfe quoted extensively, told me that he barely remembered Wolfe’s presence, and what he did remember, he did not like.

But one property of good reporting is that it transcends politics and forces an acknowledgment from the reader: Yes, that it is how it was. Fineness of observation becomes an end in itself, and if your sense of irony and detail is sharp enough, and expressed with a singular palette of acerbity, wit, and exuberance, you can get away with the most flagrant and reactionary moralism.