A stealthy prison break under the cover of darkness; a speeding getaway car that just barely evades the police; a clandestine exodus from a repressive country. Not just reserved for noir thrillers or espionage tales, dramatic escapes form the backbone of a range of stories, from classic works of literature to children’s books. These are some of our favorites.

Life After Life by Kate Atkinson

In Kate Atkinson’s spellbinding novel of mid-20th-century England, Ursula Todd is born in the middle of a snowstorm and promptly dies. She is reborn, again and again, and must escape her own death. It’s no spoiler to say that she fails, again and again. The many lives she leads entwine with the big moments in British history between the wars, but the greatest escape of all is Atkinson’s own: the novel is one long, elegant, and surprising answer to the question, “If you could go back in time, would you kill Hitler?” —Stephanie Bastek

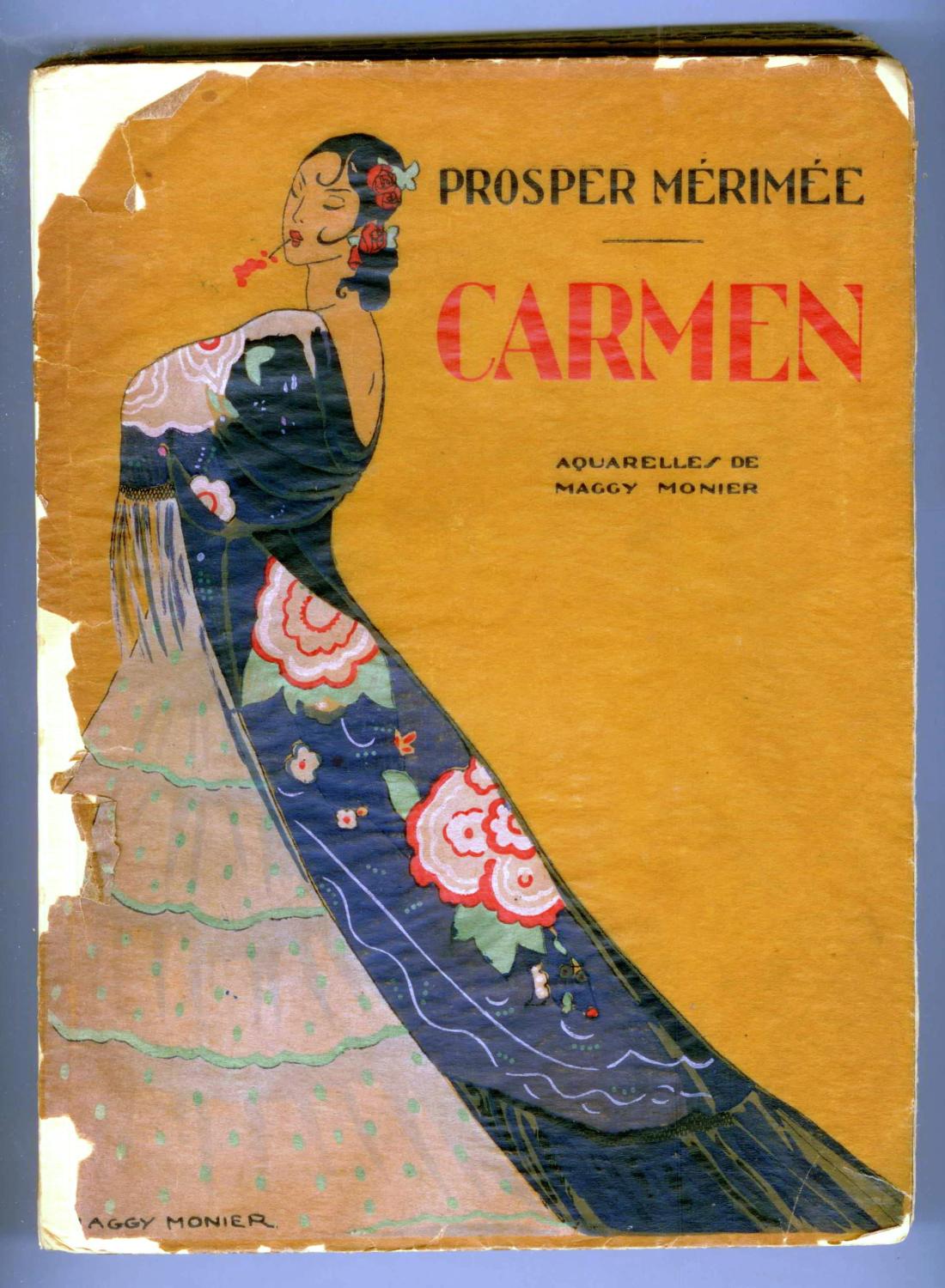

Carmen by Prosper Mérimée

Though originally from the Basque Kingdom of Navarre, José is living in Seville, working as a security guard at a cigar factory. One day, the hot-tempered Carmen gets into a fight and slashes Xs on an antagonist’s face. José is instructed to take her to prison, but along the way, Carmen begins speaking to her captor in Basque: “Laguna, ene bihotzarena—companion of my heart,” she says to him. “Are you from the Basque Provinces?” She tells him that she, too, is Basque, and that a band of Gypsies had kidnapped her, bringing her to Seville. “Ah! how I wish I were back at home,” she says, “among the white mountains! … My comrade, my friend, will you do nothing to help a fellow-countrywoman?” Against his better judgment, José allows Carmen to escape. In Georges Bizet’s operatic adaptation, this scene (at the end of Act I) is rendered as a grand seduction, with Carmen not only appealing to José’s nostalgic feelings but also tempting him with an alluring seguidilla. —Sudip Bose

From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler by E. L. Konigsburg

Who says all escapes should involve discomfort and bother? Precocious 12-year-old Claudia Kincaid is eager to break free from the stuffy confines of life in Greenwich, Connecticut, so she packs a toothbrush, clean underwear, and her younger brother Jamie, and sets off for New York City. Not for her the runaway clichés of sleeping on doorsteps and rummaging for scraps: Claudia decides that taking up residence in the Metropolitan Museum of Art will suit her just fine. Relaxing in a chair that belonged to Marie Antoinette? Check. Using the Fountain of the Muses as a personal bathtub? Check. For any child (or adult) who has ever daydreamed of running away, here is escape at its finest. —Katie Daniels

The Aeneid by Virgil

In Book II of The Aeneid, Aeneas recalls the end of the Trojan War, the Greeks tricking their way into the center of Troy and laying waste to the city they have besieged for 10 years. Amid scenes of looting and slaughter, Aeneas feels compelled to fight, but his mother, the goddess Venus, urges him to flee—after all, he must eventually find his way to Rome and found the Latin race. With his aged father hoisted upon his back, his young son walking beside him, and his wife trailing behind, Aeneas embarks on one of the most harrowing journeys in literature:

And so we make our way

Along the pitch-dark paths, and I who had never flinched

At the hurtling spears or swarming Greek assaults—

Now every stir of wind, every whisper of sound

Alarms me, anxious both for the child beside me

And burden on my back. (translation by Robert Fagles)

Aeneas loses his wife along the way, but her shade appears to him toward the end of Book II and assures him that after a long period exile, he will indeed lay claim to a distant kingdom—and marry another woman. —Sudip Bose

A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway

Two of the best escapes in American literature appear in the same book: Ernest Hemingway’s 1929 novel, A Farewell to Arms. The book chronicles the experiences of American ambulance driver Frederic Henry (loosely modeled on Hemingway himself) in Italy during the First World War. Henry is on the frontlines with Italian troops at the Battle of Caporetto when the Austro-Hungarians break through, forcing the Italians—and Henry—into frantic retreat. Soon, having fallen in love with Catherine Barkley, a British nurse, Henry effects another escape, this time from his own panicked comrades. He and Catherine undertake a dangerous journey through war-torn countryside to the Swiss Alps, where they hope to wait out the rest of the war. Read the book to see how things turn out. —Bruce Falconer

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead and Underground Airlines by Ben H. Winters

Colson Whitehead’s novel was by far the more acclaimed of the two, but I was equally enamored with Ben H. Winters’s alternate history of United States, in which slavery continued in the South to the present day. In both stories, young black protagonists escape from slavery—but that’s where their stories diverge. Where Whitehead imagines a literal railroad, and the stops along the way as different historical ideas of slavery, Winters uses the airlines as a metaphor—and draws an explicit line between historical American slavery and modern economic slavery, where children abroad and prisoners at home work for pennies, providing their labor “freely” in name only. Sentence for sentence, Whitehead’s novel was better—he’s a stronger, more melodic writer—but Winters’s ideas are worth sitting with, and I can’t turn down a good noir thriller. —Stephanie Bastek

Wartime Lies by Louis Begley

This short, partly autobiographical novel, published in 1991, tells the heart-pounding story of a Jewish boy and his aunt in Nazi-occupied Poland, who are forced to move from place to place, telling lies about their identity in order to evade capture and transport. Before they eventually escape into the countryside, they witness the uprising and destruction of the Warsaw ghetto and much else that is horrifying. But part of what haunts the boy years later, when he narrates the story, is those many necessary lies. —Robert Wilson

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen

The narrator of this luminous novel, a nameless captain, is a double-agent: an ardent communist spying on his South Vietnamese compatriots. Although he is able to escape Saigon with his general, the captain is unable to escape the tangle of his all-too human feelings for his subjects. A complicated exploration of loyalty, ideology, and the legacy of the Vietnam War. —Stephanie Bastek

The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas

How could we possibly compile a list of great escapes and not include perhaps the most famous example? Few characters in literature are as resourceful as our hero, Edmund Dantès, who is locked up without trial in the Château d’If for a crime he has not committed. (To make matters worse, he is arrested on the day of his wedding.) Dantès’s improbable and cleverly planned escape from the Bay of Marseille fortress leads to a revenge plot of symphonic dimensions. —Sudip Bose

A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens

Charles Darnay can’t catch a break. The end of A Tale of Two Cities finds him trapped in the notorious La Force prison at the height of the French Revolution, under the watchful eye of guards who are eager to test out a new weapon called La Guillotine. It’s a setup ripe for a good jailbreak, and Sidney Carton—a jaded, hard-drinking lawyer who bears a remarkable resemblance to Darnay—is the man for the job. While there’s enough action here to power a daytime soap opera, the real drama is Carton’s transformation into a man capable of heroic, unselfish action for the sake of the woman he loves (who, of course, just happens to be Darnay’s wife). —Katie Daniels

The Sherlock Holmes Collection by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

In story after story, Sherlock Holmes foils escape attempts by others, including the infamous Professor Moriarty. Even more impressive is Holmes’s own escape from Moriarty. This episode, made famous by numerous adaptations, concludes The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes. (Take note, because this is the vital reason you must read the complete collection of Sherlock Holmes tales and not simply the selected stories.) While I don’t want to spoil the drama of the Reichenbach Falls, I will say that the book ends on a literal cliffhanger, and against all logic, five more books featuring Holmes follow, including The Hound of the Baskervilles. If that isn’t the greatest escape in literature, I don’t know what is. —Taylor Curry

Dogs at the Perimeter by Madeleine Thien

Another escape/non-escape! Dogs at the Perimeter asks whether we can ever escape our own memories. Janie escaped the Khmer Rouge as a child and found refuge in Montreal, and, later, in the psychology lab of her colleague and friend, Hiroji Matsui. But after Janie abandons her family—and Hiroji disappears—she is forced to reckon with the scars of her past. I first fell in love with Madeleine Thien through her book Do Not Say We Have Nothing (check out my interview with her here), and this novel, though on a smaller scale, is no less impressive. —Stephanie Bastek