Typically characterized as a fantasy novel, Vincent McHugh’s 1943 I Am Thinking of My Darling imagined New York City in the grip of a tropical virus that rendered the infected void of any moral sense, particularly with regard to sex and fidelity. The city came to have the “unmistakable feel of a place with its hair down and a flower dangling over one ear,” its residents exhibiting “no more morals than a tomcat.” Yet for all the comic fornication and unconcern for consequences, the novel presented this radical changing of habits—“The toughest social force there is, probably”—as a genuine public crisis, the act of a society undergoing self-inflicted disorganization.

Two years later, when President Truman announced that the war with Japan was effectively over, San Francisco experienced 72 hours of social disintegration beyond anything in McHugh’s novel. An August 1945 Life magazine feature on the victory celebrations nationwide captured some of the mood in San Francisco. One photo shows a couple of attractive blonds skinny-dipping in a pond near the Civic Center, and another shows a small group of sailors looting a liquor store and passing out bottles. Life’s caption is admirably direct: “In San Francisco sailors break into a liquor store and pilfer the stock. Revel turned into a riot as tense servicemen, reprieved from impending Pacific war-zone duty, defaced statues, over-turned street cars, ripped down bond booths, attacked girls. The toll: over 1,000 casualties.” Direct as it is, however, the caption hardly captures the scale of the “peace riots” that convulsed San Francisco. Among the casualties were 13 fatalities and six women medically treated for rape, though shocking eyewitness accounts suggest that the incidence of sexual assault ran far higher than that. (The riots form the backdrop of Niven Busch’s 1946 novel, Day of the Conquerors.)

However extraordinary, McHugh’s “fantasy” and San Francisco’s nightmare are representative of the war years, when America not only pulled together industrially and militarily but also fell apart socially without ever fully coming back together. It all began with a huge increase in defense spending, which—after a long depression—helped boost the economy and with it the marriage and birth rates. But even before war’s end, things had gone haywire on the home front. By 1945, an unprecedented one in three marriages ended in divorce, up from one in five as recently as 1940, and the rate was still climbing. Rapes were up 27 percent in 1944 compared with the prewar average, and rape statistics were much higher among youths, with the total number of juvenile delinquency arrests (for a variety of serious offenses, including rape) 100 percent greater in 1945 than in 1939. Magazines of almost every stripe were fretting about an epidemic of venereal disease, with Ladies’ Home Journal reporting that in 1944, “11,000 girls between the ages of eleven and fifteen acquired syphilis.” Illegitimate births had increased, and had done so most sharply—according to Jane Mersky Leder, author of Thanks for the Memories—among the 20-something wives of military men. Then again, also according to Leder, a 1945 U.S. Army survey found that 80 percent of “GIs away from home for two years or more admitted to regular sexual intercourse. Nearly a third of these men had wives at home.”

Being away from home is the great variable here. Roughly 16 million Americans were in uniform during the war, most of them billeted far from home, usually overseas. However, contrary to popular assumptions, relatively few of those in the military at the time (roughly one in 16) saw combat. Most Americans who served in the war did so in rear-echelon posts or while performing occupation duty in conquered or liberated nations. That generation’s famed reluctance to speak about its war experiences is likely to be rooted less in painful memories of seeing friends die in combat than in painful memories of seeing friends (possibly married) swindle and sexually coerce desperate civilian girls in some war-ravaged city, or in painful memories of doing so oneself. The protagonist in Sloan Wilson’s The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, for instance, is less burdened by memories of killing in combat (even accidentally killing a friend) than by memories of cheating on his wife and siring a love child with a destitute Italian woman.

But it wasn’t just GIs who were away from home. Nearly as many American civilians (adults and children) found themselves uprooted owing to the war, primarily to answer the call of war-related industry and the siren song of high wartime wages. The cumulative social dislocation, military and civilian, involved 20 percent of the American population, and for civilians, the new settings could seem as foreign as those the soldiers experienced overseas. In his first novel, The Town and the City (1950), Jack Kerouac put a typically lyrical touch on the upheaval:

It seemed as though a whole nation of men and women were beginning to wander with the war. They traveled on trains and busses and their familiar unknown faces were suddenly everywhere. In far-away towns where eleven o’clock had once been silence and the swish of treeleaves and the sleepy rush of Pinefork Creek, and the echoing howl of the Eleven-O-Two, now it was the crowds of warworkers hurrying for the busses and the midnight shift at the vast swooping sheds three miles out of town.

This country-come-to-town immersion in the shadowy, hustling night world of factory and city is part of what made wartime film noir so resonant. It was a strange new environment, with a significant itinerant population full of questionable characters, men and women alike, a world in which too many American youths ran unsupervised and lost their way.

Of course, large numbers of young people were happy to quit school for the prospect of making good money in an economy that needed all available labor. The war, noted Francis E. Merrill in Social Problems on the Home Front (1948), reversed a trend toward decreasing reliance on adolescent labor and “established a temporarily unlimited demand for young persons in the armed forces and industry.” Thus did the war crack open a generation gap:

One of the concomitants of this increased adolescent independence was the comparison made by many adolescents of their own earning power and that of their parents during the depression. Many adolescents remembered vividly that their fathers were unable to find work ten years before. Others remembered that their parents worked at lower wages than they (the children) were earning during World War II. The economic reasons for this abnormal situation were not apparent to the majority of young people who imputed, consciously or unconsciously, an inferiority to the father and by comparison a certain superiority to themselves.

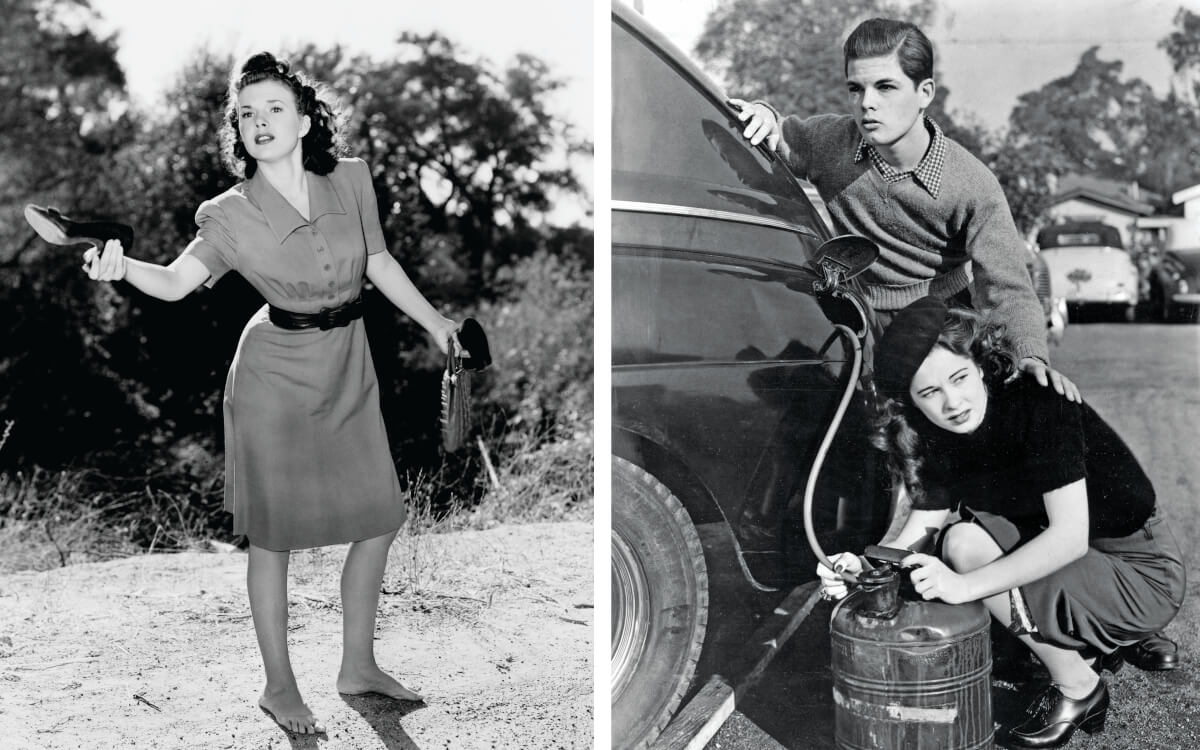

The theme of headstrong, ungoverned youth—deprived of proper guardianship, perhaps following the example set by dissolute adults—informed numerous magazine articles, novels, short stories, and movies of the war years and into the decade beyond. Several movies made during the war, along with the short public service film As the Twig Is Bent (1944), came at the theme directly (if ploddingly): Where Are Your Children? (1943), Are These Our Parents? (1944), Youth Runs Wild (1944), I Accuse My Parents (1944).

Using wartime dislocation as a narrative device, writers and moviemakers in the immediate postwar years continued to lay the groundwork for what would become a juvenile exploitation industry in the coming decades. See, for instance, Elisabeth Sanxay Holding’s crime novel The Blank Wall, with its pornography and blackmail, and Irving Shulman’s youth gang drama The Amboy Dukes, with its drugs, rape, and murder—both from 1947. Into the ’50s, the war continued to be invoked as the source of a generational problem plaguing America. The 1950 film So Young, So Bad and the 1955 movie adaptation of The Blackboard Jungle both cite the war’s contribution to juvenile delinquency. But this wasn’t just a conceit of writers and moviemakers. While being interviewed on a 1953 episode of The Kate Smith Hour, Senator Thomas C. Hennings—who was part of a subcommittee investigating the causes of and possible cures for juvenile delinquency—suggested that the country might be “harvesting some of the bitter fruit of the Second World War.”

With this connection so naturally assumed in the American imagination, one begins to see the war informing—or at least informing the reaction to—works in which the war has no apparent role. The 1945 movie adaptation of Mildred Pierce (1941), for instance, with its divorced, entrepreneurial mother and its predatory adolescent daughter, almost certainly struck viewers as topical in a way James M. Cain never imagined when he wrote the book. And in the 1950 movie Gun Crazy, a delinquent boy brought up without parents meets a girl who has been blackmailed into sexual servitude and who is part of a low-grade traveling circus—all of which evokes the dislocation, transience, and virtual orphanhood of the war years. Only after a quickie marriage does the boy discover the girl’s ruthless acquisitiveness and his unwitting enlistment in satisfying it, a scenario that recalls (in exaggerated form) so many hasty wartime marriages that women were suspected of entering into only for the military allotment checks and the possibility of an insurance claim should their husbands perish in the line of duty. Such marriages often met the death the husbands didn’t, and contributed to the great rise in divorces that attended the war and its aftermath.

Films like Where Are Your Children? and Youth Runs Wild played to larger anxieties about the war’s deleterious effect on social norms. (Everett Collection)

It was typical—in this battle of the sexes within the larger war—for women and girls to be portrayed as the aggressors and transgressors and for men and boys to be portrayed as largely guiltless (or if guilty, forgivably so, under the circumstances). If young people were caught having sex, for instance, he’d most likely be dismissed for sowing his oats while she’d most likely be deemed guilty of a crime against common decency. He could be found guilty of rape, were coercion involved, but if the girl had given consent, she alone was to blame. This double standard accounted for a distortion in juvenile delinquency statistics, which showed a shocking increase in the number of female offenders relative to the increase among males—the result of the many instances in which girls were singled out for a “sex crime” that involved an uncharged male accomplice.

For married couples, likewise, husbands away at war were almost expected to cheat, while wives were supposed to wait faithfully, and only the latter’s breach mattered. In William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), bombardier Fred Derry comes home from overseas to find that his hard-partying war bride has been consorting with other men while he was gone, a discovery that wounds him. What goes unmentioned in the film but which is explicit in MacKinlay Kantor’s Glory for Me (1945), on which the movie is based, is that Derry was himself enjoying some hard-partying extramarital activities overseas.

Derry was also enjoying the status and camaraderie that came with mass mobilization, an ennobling feeling of being part of something much larger than oneself—a feeling that was harder for American wives, girlfriends, and daughters to experience. Some women approximated it with war work, especially the relative few who did so in heavy industry, but for most, the sense of being part of a great communal undertaking was harder to achieve. Instead, they navigated the tumultuous times on their own, a phenomenon captured in Dorothy Parker’s short story “The Lovely Leave,” from the December 1943 issue of Woman’s Home Companion. In it, a bride is discombobulated to learn that her Air Corps husband has been granted a brief, unexpected leave while in transit. The news produces a painful onrush of hope just when stoicism had proved most effective for coping with marital separation. The story reverses any notion that the home front was a largely intact whole from which the country’s fighting-age men had been scattered to lonely extremes. Witnessing her husband’s intense camaraderie with his fellows in arms, and comparing that with her hollowed-out existence, the wife remarks, “You have a whole new life—I have half an old one.” Desperate to please and to be found irresistible by her husband, she ends up instead feeling like a third wheel in his relationship with the army. That women in such circumstances should sometimes find comfort in the arms of another is no less sympathetic than that men far from home should sometimes do the same.

Nowhere was the sexual double standard more pronounced than in the wartime reaction to venereal infections, the incidence of which rose alarmingly despite a crackdown on prostitution rings that had been operating in stateside garrison towns. The spread of VD was instead attributable to what a committee of the American Social Hygiene Association called “sex delinquency of a non-commercial character” and what others called “promiscuity not for hire.” That is, a vast number of young women and underage girls—with little discouragement from men—were caught up in the urge to do what was euphemistically called their “patriotic duty.” These women and girls, who as a group went by various names (“Good Time Charlottes,” “Victory Girls,” “Patriotutes”), were taking advantage of radically shifted national priorities and pressing national distractions to do what young people of any era are wont to do if given half a chance.

But if anyone caught a dose, the blame was entirely on the women and girls, a fact reflected in hygiene-oriented war posters—for instance, one showing a cherubic lass who “may look clean” but is liable to “spread syphilis and gonorrhea.” Other posters employed a lurid visual style that anticipated the covers of later exploitation novels, the sort that feature, in the words of Raymond Chandler, “shiny girls, hardboiled and loaded with sin.” Of those, one featured a femme fatale who’s labeled a “Juke Joint Sniper.” Another referred to its sleepy-eyed dame as a “Booby Trap”—a title that, like “Juke Joint Sniper,” is worthy of exploitation fiction as well.

Still others ventured beyond foul temptresses and into the realm of pure horror, presenting VD as either a cadaverous female or a skull-faced woman in an evening dress. Of the former type, one shows a pretty feminine mask separating itself from the ghoul underneath, the caption reading, “disease is disguised.” In all of the aforementioned posters, VD isn’t something to which men and women are equally vulnerable, something they might catch from one another and against which both need to be on guard. Instead, as presumably the original and only source, sexually available women essentially are the disease.

One problem with ascribing sexual delinquency exclusively to wayward American females was how to account for the fact that American military men, even in theaters of war, were just as prone to sexual delinquency as the women they left behind. As soon as GIs started showing up in Britain—operating out of airfields for bombing campaigns over the continent, being massed for the invasion of France—the incidence of illegitimate births and VD infections began to rise. The problem persisted following the invasion of Normandy. By December 1944, as Mary Louise Roberts writes in What Soldiers Do, the rate of VD infection among American troops in Europe was almost 200 percent higher than it had been as recently as September of that year.

Of all people, it was the very masculine James Jones who evinced perhaps the greatest empathy, and sympathy, for the slut-shamed, sexually active American women of World War II. In From Here to Eternity (1951), Karen Holmes, the wife of Captain Holmes and the secret lover of Sergeant Warden, at first seems like a woman off a wartime hygiene poster: a booby trap, a sexual sniper. She has a reputation among the unit for being a diseased tramp, primarily because another of the unit’s members, Sergeant Stark, previously picked up a dose from her. It’s later revealed, however, that the once-faithful Karen had contracted gonorrhea from her own husband, who’d contracted it during one of his routine sexual indiscretions. In despair over his betrayal, she began straying herself, during which time she infected Stark. Ultimately, treatment for her infection required a hysterectomy.

Done wrong by her husband, her reputation shot, the meaning of sex gone for her since she can no longer bear children, she is one of the most pathetic, sympathetic characters in a novel full of them. And, the book suggests, if anyone deserved to be on a hygiene poster as a filthy menace in respectable disguise, it was Captain Holmes and men like him.

Blame for the spread of venereal disease fell entirely on women, a fact reflected in these hygiene-oriented posters from the war years. (Alamy)

As if in confirmation of all this exclusively female turpitude (though having to do largely with the War Production Board’s rationing of fabrics), women’s fashions became much more revealing during the war. Women appeared at work and at social gatherings bare-armed and bare-backed, perhaps with plunging necklines and certainly with rising hemlines, and they roamed beaches in what came to be called the bikini but what then looked like a bra-and-panty getup not meant to be worn outside one’s boudoir, let alone one’s house. As with young women euphemistically “doing their patriotic duty,” these figure-baring, fabric-saving fashions were deemed “patriotic chic.”

Women also started cultivating an air of girlishness in their clothing choices. In 1943, Life struck an almost Lolita-ish tone in discussing the phenomenon: “This summer, children, girls and women all dress alike. … In these kid clothes [rompers, jumpers, pinafores] the female leg becomes notably conspicuous as women and girls loll around in the shade or roughhouse on the lawn.”

The war years, which witnessed a decrease in the average age of first-time mothers, also saw the introduction of what Life called “junior miss” maternity styles. “Only the youngest of young mothers can wear such styles,” Life noted. A touching photo caption accompanying the article further observed, “Young mothers like them because they resemble, in cut and bright colors, clothes they have recently outgrown.”

It didn’t take long after war’s end and a lifting of fabric restrictions for styles to change. Hemlines dropped, necklines rose, and armholes deepened. Pleats, pockets, and bows returned. Waists were pinched, hips were rounded, breasts were lifted, shoulders were ruffled, and gloves were cuffed as a Gibson Girl femininity replaced that of the nymphet in her dishabille and the femme fatale with her sleek, angular appeal. And as with the revealing styles of the war years, the more rounded and restrictive styles of the postwar years came to be seen as symbolic of broader social and sexual attitudes. Out was the now mostly overlooked libertinism of the 1940s, and in was the never forgotten (often misrepresented) repression of the 1950s.

According to the narrative of postwar repression, Rosie the Riveter had to surrender her lunch bucket and dungarees, get dolled up, and content herself with household drudgery (Rosie representing all women so oppressed); daughters were groomed for an extended virginity; and the patriarchy enjoyed such unchallenged complacency that its main function in national lore has since been to serve as the darkness before the dawn of the 1960s. But given what everyone had just gone through, there’s a conspicuous lack of retrospective sympathy (and a degree of special pleading) in that narrative.

Rosie and her ilk accounted for about 10 percent of the women employed during the war. The greater number by far were those who held office jobs, particularly in the growing, multiplying bureaucracies of the nation’s capital. The rush of young female workers to D.C. was enough to cause an acute housing shortage—the backdrop of such works as Faith Baldwin’s 1942 romance novel, Washington, USA, and George Stevens’s 1943 bedroom farce, The More the Merrier. Also, despite the layoffs that women (and men) suffered in the immediate aftermath of the war, by 1950 women’s presence in the workforce had more than rebounded. The number of women employed that year was 41 percent greater than in 1940, with almost half the female workforce made up of married women with husbands present, patriarchy be damned.

It’s true that the median age of employed women rose from roughly 32 to more than 36 from 1940 to 1950, indicating that much of the female workforce in 1950 was made up of married women who had reached or were nearing the end of their mothering years, and that—correspondingly—younger mothers did tend to be more homebound. Leaving aside that a certain percentage of homebound mothers, then as ever, must have found childrearing an important and satisfying occupation, even those who dreamed of wider horizons and more varied opportunities were living in the shadow of the war, and specifically of the war’s effect on children. Given what came before, young parents of the postwar years—mothers and fathers alike—probably agreed on the need for increased childcare and supervision compared with what had been common in the war years (when the term latchkey children first came into use, along with eight-hour orphans and shipyard orphans).

It’s also true that roughly a decade later, in 1961, the pollster George Gallup reported finding American youths to be an apathetic, overindulged, overprotected lot. Such depleted vigor, however, was at least in part a side effect of childhoods that had been stretched out too long by parents over-reacting to problems associated with childhoods that, in recent memory, had ended far too early, and abruptly.

As for the midcentury American male, who is cast as having enjoyed and exploited all advantage, he’d spent most of 15 years poor or in uniform (and possibly in harm’s way). Whatever the case, he and the women of his generation typically entered upon a more conservative path in the postwar years. After such widespread, transgressive upheaval, how could they have done otherwise? For those who had lived through the Depression and the war and their attendant social pathologies, prosperous, stable, nuclear families didn’t seem distastefully conventional. Prosperity and stability were delicate things that had only recently been coaxed into existence after much suffering, and convention seemed a means of both consolidating and perpetuating these new gains. It required the passage of time and the emergence of a new generation for prosperity and stability to be taken for granted and for convention to seem constrictive of a purer, more honest way of living.

The social strains of World War II, it should be noted, were not unprecedented. Doughboys had picked up plenty of VD in France during World War I, and the spread of automobile ownership, already decades in the making by World War II, had been affecting everything from living patterns and church attendance to teenage dating habits, the latter mostly by helping teens shake off adult supervision. (The war’s own influence on churchgoing wasn’t stark, but a longitudinal Gallup study does suggest a 10 percent drop in weekly church attendance among Protestants from 1939 to 1950. This dovetails with Life’s 1941 observation that booming defense towns weren’t known for their religious character. One such town, for instance, boasted more than 300 bars and strip clubs but not a single Protestant church.) And almost since the first recording of divorce rates in 1887, the clear trend was toward a steady, modest increase.

But World War II, like other periods of upheaval, produced social changes that were too accelerated to be allowed to continue. Thus, if it’s fair to say that the sexual revolution of the 1960s was a backlash against the more conservative climate of the 1950s, it’s just as fair to say that the more conservative climate of the 1950s was a backlash against the sexual revolution of the 1940s.

At any rate, as the new generation came of age, so did its awareness of grownups’ hypocrisy. How could mom and dad profess and enforce such a buttoned-down attitude toward sex when, in their younger days, everything from magazines to calendars to the nose sections of four-engine bombers was adorned with barely legal Vargas Girls, Petty Girls, and the like, and when Esquire found itself in a legal dispute with the postmaster general over whether its illustrations amounted to pornography? When, in mom and dad’s younger days, the sexually dangerous women of noir (Ava, Lana, Rita) ruled the screen? When—although they enjoyed hit songs about restraint, fidelity, and self-denial, songs like “I’ll Walk Alone,” “Till Then,” and “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore”—many in mom and dad’s generation, if not with the ones they loved, were loving the ones they were with? When, precisely because young people of mom and dad’s generation were not abstaining, hygiene posters portrayed women as everything from sluts to skeletons?

There’s hypocrisy in that unhealthy jumble, but it’s hypocrisy born of often firsthand awareness of consequences. The restraint in those old songs and the later hypocrisy of postwar parents are part of an adult reckoning with, and respect for, hard realities, as Mary Gaitskill gracefully observed in her 2005 novel, Veronica, in which the narrator muses on an old wartime ballad:

A song my father especially loved by Jo Stafford was “I’ll Be Seeing You.” During World War II, it became a lullaby about absence and death for boys who were about to die and kill. I’ll be looking at the moon, but I’ll be seeing you. In the moonlight of this song, the known things, the tender things, “the carousel, the wishing well,” appear outlined against the gentle twilight of familiarity and comfort. In the song, that twilight is a gauze veil of music, and Stafford’s voice subtly deepens, and gives off a slight shudder as she touches against it. The song does not go any further than this touch because beyond the veil is killing and dying, and the song honors killing and dying. It also honors the little carousel. It knows the wishing well is a passageway to memory and feeling—maybe too much memory and feeling, ghosts and delusion. Jo Stafford’s eyes on the album cover say that she knew that. She knew the dark was huge and she had humility before it.

The dark was even huger than Gaitskill’s combat focus suggests. Killing and dying, in some sense, weren’t the half of it (think again of The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit). Turning from Jo Stafford to the rock ’n’ roll of the later ’60s, the narrator continues: “The new songs had no humility. They pushed past the veil and opened a window into the darkness and climbed through it with a knife in their teeth.” Alluding to lyrics by such bands as The Doors and the Rolling Stones, she observes that even if a song “was about killing and dying—that was just another place to go.” Many pages later she concludes, “We were stupid for disrespecting the limits placed before us. For tearing up the fabric of songs wise enough to acknowledge limits. … But we were right, too. We were right to do it even so.”

She’s talking, obviously, about more than Tin Pan Alley reticence here. Indeed, it’s every generation’s right, almost obligation, to make its own mistakes, in its own fashion—to learn old lessons in a way that feels new if only because one is learning them for the first time.

Experience is the best teacher. The postwar moms and dads had it, but it was nontransferable, as it always is.

Twenty-five years after it was published, Vincent McHugh’s I Am Thinking of My Darling was made into a movie. With a humorous take on anomie, McHugh had essentially asked, “What’s so good about feeling good?” What’s so good about everyone pursuing individual bliss if doing so jeopardizes public order and even the public spiritedness on which we all rely, and which helps ensure the functioning of everything from mass transit to emergency services to the self-governed interactions of the city’s multitude?

The movie is perfectly forgettable, except for the interesting fact that Hollywood, in 1968, reversed McHugh’s sentiment and, in a leading fashion, titled the adaptation What’s So Bad About Feeling Good? On the big screen, the dogged functioning of New York City is taken for granted, and the focus instead is on metropolitan manners. Old-timers are grouchy, the counterculture is disillusioned, the city fathers are cynically preoccupied with tax revenues and reelection, and only dissociation and whimsy can save one’s soul.

With ready access to contraception and antibiotics, it might have seemed at the time, at least sexually, that there wasn’t much bad about feeling good anymore. Further, there was hope that if people adopted an “I’m okay, you’re okay” attitude, the abolition of standards (to each his or her own) would obviate social tensions and instabilities. Finally, if everyone mastered his or her own jealousy, ditching it like an inherited hang-up, people really could love the one they’re with, without hurting the one they love, and could—unmoved by jealousy—learn of their loved one’s doing the same.

That sounds about as gratifying as Karen Holmes’s sex life in From Here to Eternity, a series of encounters mostly robbed of meaning by her wandering, indifferent husband until she and Sergeant Warden developed a more exclusive bond, one lit by frictions of a sort that, for better and for worse, give love and sex an emotional intensity far more lasting than any physical sensations. The men and women of that generation learned that there was no such thing as free love, and as parents they tried—overmuch, perhaps—to protect their kids from paying too dearly upon their own sexual awakenings. But there’s almost no greater confidence builder than naïveté, so those kids eventually shook off the torpor in which George Gallup had found them and launched a sexual revolution, certain that they’d get it right where their parents hadn’t. It was the triumph of hope over experience. And in the end, experience won.