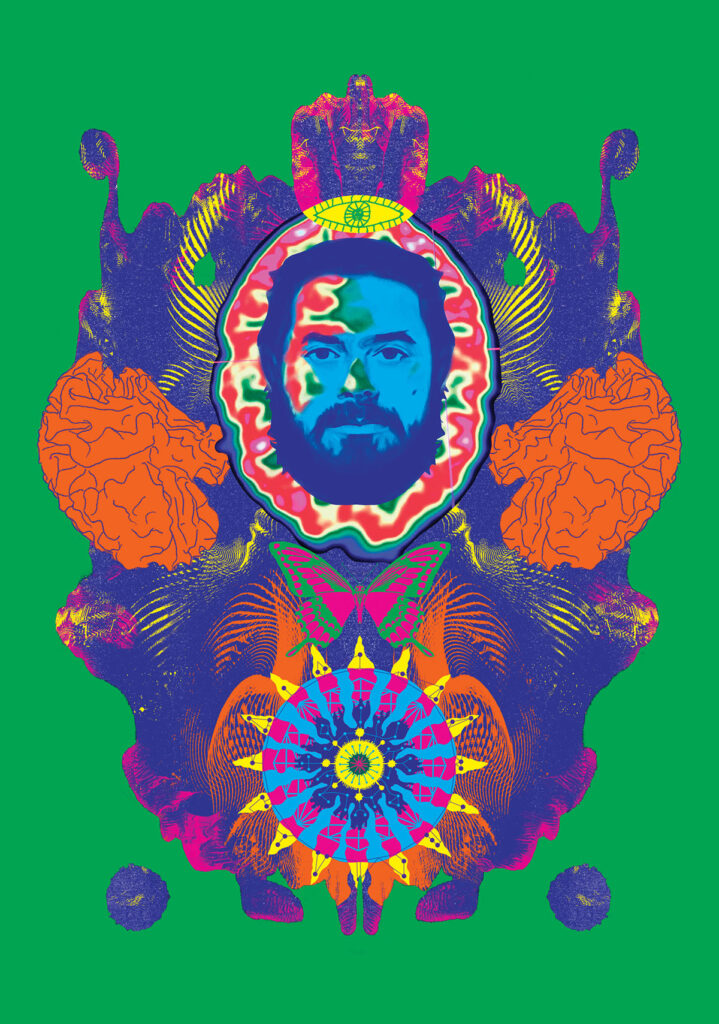

The Grinberg Affair

One of Mexico’s most curious missing-persons cases involves a scientist who dabbled in the mystical arts

Anyone who sees Aher, Elisha ben Avuya, should be concerned about

calamity, as he strayed from the path of righteousness.

—Talmud Berakhot 57B:6

I

All these years later, everyone who knew Dr. Jacobo Grinberg Zylberbaum is still puzzled by his mysterious disappearance. How could this famous Mexican neurophysiologist have vanished without a trace? Grinberg was a few days shy of 48 when he was last seen, on December 8, 1994. Almost immediately, rumors began to circulate: that the CIA had kidnapped him; that he feared for his life to such a degree that for weeks, maybe months, he had slept in a van; that he had become so absorbed in his explorations of shamanism in Mexico that he lost his wits and simply faded through the fissures of reality.

No corpse was ever found, meaning there was no funeral, no seven-day shiva, no matzevah, or tombstone, to mark a gravesite. In Mexico, the tributes were many. The newspaper Reforma described Grinberg as “the Einstein of human consciousness,” a moniker that by any account is a stretch. Journalist Sam Quinones wrote a long profile of him. And one of Mexico’s top sleuths, Comandante Clemente Padilla, director of the Ministerio Público Especializado, conducted a thorough criminal investigation that was eventually called off under dubious circumstances—purportedly at the behest of someone linked to the nation’s president at the time, Ernesto Zedillo. The Mexican media declared Grinberg a desaparecido—a disappeared person, presumably killed or secretly imprisoned for political reasons—a nomenclature that remains confusing because, for most of his life, Grinberg was anything but political.

The author of more than 50 books, Grinberg was a trained psychologist, though his interests ranged from telepathy to paranormal activity, from Kabbalah to Hinduism. How to characterize his books La luz angelmática (The Angelic Light) and Los cristales de la galaxia (The Crystals of the Galaxy), which argue that humans are atavistic creatures imprisoned in their own epistemological squareness? Some of his work deviates into sci-fi terrain, à la Philip K. Dick. Other writings recall the work of George Ivanovich Gurdjieff, the philosopher-mystic who was part monk, part yogi, and part fakir. It is perhaps not surprising, then, that the Grinberg affair would receive interest from unconventional quarters. I once heard from a person claiming to have seen Grinberg in January 1995 in western Mexico—boarding a spaceship made of three perfectly delineated spheres. And in 2020, El secreto del doctor Grinberg (The Secret of Dr. Grinberg), a documentary directed by Ida Cuéllar, made the rounds of several film festivals. It argued that Grinberg had come to learn things about the human mind that the rest of us shall never know.

Buried in all the overstatements, however, is the story of an ambitious scholar who had embarked on an honest, enlightening quest, one that pulled him in countless, at times incompatible, directions. My interest in the story is more wholesome than that of the lurid sensationalists, more grounded, and more personal: Dr. Jacobo Grinberg Zylberbaum was my relative, although not by blood. My aunt Hilda Elterman was his cousin. He is what in Mexican Spanish we call un pariente político, political family. Truth is, I rarely interacted with Grinberg, and over an extended period of time, I thoroughly disliked what he symbolized: the wacky, unreliable scientist. In my opinion, his use of neurobiological terminology to explain such phenomena as psychokinesis, telepathy, levitation, and retrocausality—as he did in the research papers published early in his career—was highly dubious. He experimented with children in ways that seem suspect, not to say frightening. And he surrounded himself with groupies who, instead of testing his ideas, bowed to his charismatic personality. Still, I have softened my perspective in recent years. Although Grinberg still strikes me as cuckoo, I find his intellectual odyssey admirable, not in what it produced but in how it sought to harmonize disparate fields of knowledge. He was, I believe, a heretical scientist on a mission.

II

When I was growing up in Mexico City, Grinberg was on the faculty at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), the country’s top university, its campus located a mere two blocks from my house. Grinberg had a lab, the Instituto Nacional para el Estudio de la Conciencia—the National Institute for the Study of Consciousness—apparently staffed only by himself and his loyal assistant, Ruth Cerezo. One could well have believed it to be a large operation, however, given the kind of press that he received for his research on out-of-body experiences and the alternative channels of human consciousness.

I met him only twice, both times in passing. The first encounter was during a family gathering, when I was still in high school. The only thing I remember is my mentioning to him that I had read, not long before, Carlos Castaneda’s The Teachings of Don Juan, about the use of peyote and other psychedelics among Yaqui shamans. He smiled and replied something to the effect of, “Beware of secret wisdom, for it may enwrap you.” Then, if memory serves me, I saw him in 1981, when I was 20. I don’t remember anything specific about that encounter, not even where it took place. But an impression of him lingers in my mind. Short, chubby, with a carefully manicured beard, he looked to me a near clone of Sancho Panza. I recall sitting in the car with my mother before the encounter as she told me about Grinberg’s teoría sintérgica, or “syntergic theory.” I didn’t know what syntergy meant. (I still don’t.) She said that Grinberg was interested in the capacity of the human brain to perceive aspects of reality beyond sensorial stimulation. My mother, who was also a psychologist, lauded him for being extraordinarily prolific. She also said he was petulant, stubborn, and temperamental.

Starting in 1987, Grinberg released his magnum opus, a six-volume study titled Los chamanes de México (The Shamans of Mexico). Before I emigrated from Mexico to New York, I tried to get my hands on these books, but they were hard to find. Then, Grinberg slipped out of my mind. More than a decade would pass before I thought of him again. One day, my mother phoned from Mexico to inform me that for months Grinberg had had no contact with anyone: not even with his daughter Estusha Grinberg, his two brothers, or Aunt Hilda, with whom he had been very close. Ruth Cerezo didn’t know where he was. Neither did his students or the chair of his department at UNAM.

Sometime later, I laid eyes on Los chamanes de México. In it Grinberg argued that Mexico exists in a state of subjugation to foreign colonial forces that have made it, over the centuries, lose its sense of self. Mexicans, he wrote, suffer from an inferiority complex, kneeling down to what appear to be more powerful systems of thought inherited from Western civilization—especially when it comes to a rational understanding of the self. But underlying the Mexican soul, he wrote, is a deeply rooted tradition of rebellion, thanks to which indigenous visions held by the Aztecs, Maya, Inca, and other pre-Hispanic civilizations remain intact. It is a matter of looking for them, which takes effort.

The style of Grinberg’s volumes is discombobulated and dense: imagine Martin Buber writing in a state of stupor. Repetition proliferates. Anecdotes mix with psychological theories without any proper context. There are typos everywhere and footnotes nowhere. The reader has the impression of being taken by the hand and guided by a Virgil who is at once hazy and prone to chaos. Every few pages, a black-and-white photo portrays shamans in action, but the poor quality of many of these images makes it impossible to say what’s going on. Indeed, the volumes seem not to have gone through any type of editorial process. This was makeshift publishing at its most audacious. Still, in terms of scope and determination, Grinberg’s study of Mexico’s shamans is unprecedented. Where the material lacks rigor, it abounds in vivid, direct experience.

III

Jacobo Grinberg Zylberbaum was born in Mexico City on December 12, 1946, during a period of rapid modernization in the country. President Lázaro Cárdenas, who had just finished his six-year term, was known as a strong leader who had helped lift the working class out of poverty and had recognized the plight of Mexico’s indigenous population, often forgotten by the ruling elite. Meanwhile, the Jewish state of Israel would soon be created (after the end of the British Mandate in Palestine), the first time such an entity would exist since the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE. These two realities—the resurgence of Mexico’s indigenous culture and the recognition that diaspora Jews could now opt to make Aliyah (ascendance) and become citizens of Israel—marked Grinberg’s education.

His family members were Yiddish-speaking Jews from Poland who had arrived in Mexico in the early years of the 20th century. Some were Orthodox. They had escaped pogroms in the so-called Pale of Settlement, the portion of the Russian Empire’s western region where Jews were allowed temporary residency. I have found little about Grinberg’s relationship with his father, but his mother was a significant figure in his life. (His parents were first cousins, a fact that worried the family when the couple announced the engagement.) Diagnosed with a brain tumor in 1956, she died from a stroke two years later. Grinberg was 12 at the time, the oldest of three brothers. As one might expect, this period proved traumatic. Such was his early dependence on his mother that for the rest of his life, he was never able to deal with women. He would fall in love quickly and easily, but the relationships would not last. Aunt Hilda remembers that after the death of his mother, Grinberg became obsessed with otherworldly events. In most of the photographs of him taken after that time, she added, he is shown gazing upward or in a distracted state, “his attention wandering and wondering.”

In 1963, Grinberg went to Israel, where he lived for a year on a kibbutz near Gaza and fell in love with his first wife, Lizette Arditti. He was not yet 20. On the kibbutz, he met a British medium who organized séances using the Ouija board to communicate with the dead. The exercise fascinated him. Rather than seeing it as an entertaining game, he thought seriously about the possibility that the dead aren’t altogether gone but are instead in limbo and might one day contact the living. Arditti recollects his stating, for instance, that a spirit had advised him that at a certain hour of the day—say, six p.m.—Grinberg’s watch would stop. Indeed, his watch stopped at that precise moment. Whether this was coincidence or evidence of genuine contact with the dead didn’t matter. For Grinberg, an area of further discovery had materialized right in front of him.

It was also during his first trip to Israel—he would return there on many occasions—that he discovered the depth of Kabbalistic thought, visiting the city of Safed in the Galilee. After the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492, and especially during the 16th century, Safed became a magnet for Sephardic rabbis with a penchant for mysticism. It was there that Moshe Cordovero, Yosef Karo, and Shlomo Halevi Alkabetz composed their treatises, including the Shulhan ’arukh (1565), the most important compendium of Jewish law. And it was in Safed that Isaac Luria, known by the Hebrew acronym Ha’ARI, founded a school of followers who explored meditative practices as well as such concepts as tzimtzum (the idea that God underwent self-contraction, thus producing emanations of light), shevira ha-kelim (the shattering of the divine vessels, or sefirot), and gigul (the transmigration or reincarnation of the soul). These concepts, concerned with visions of ascent to heavenly places and the throne of God, inspired Grinberg. Throughout his career, he would look for strategies to integrate them into his academic investigations. Aunt Hilda told me that when their grandfather, an Orthodox Jew, died in Mexico, Grinberg specifically requested all of his prayer and religious books. “He always had them next to him,” she said. “They made him feel attached to his ancestry.” Years later, when he bought a small cabaña in the state of Morelos, some 55 miles from Mexico City, he named the place Safed.

Upon returning to Mexico, Grinberg enrolled at UNAM to study psychology. Then, as he fell under the influence of the 1960s counterculture, a personality shift took place. He left his first wife and moved to New York City, where his perspective on parascientific phenomena became more radical. He enrolled in a doctoral program in psychophysiology (a precursor of neurometrics, the science of understanding the electrical activity of the human brain) at the Brain Research Laboratory, founded by the renowned neuroscientist E. Roy John at NYU’s medical school. Grinberg focused on the electrophysiological effects on the brain of such stimuli as geometric shapes and colors. But scientific research felt too square for him. It didn’t account for alternative ways of knowing. In 1977, he returned to Mexico and began teaching at UNAM. A portion of his time was dedicated to making inquiries into memory, visual perception, and physiological psychology.

At his lab, Grinberg attempted to prove that children were able to communicate via means beyond language, especially through sight. He claimed that he could make children read the words on a page without their actually looking at them. But, in an inadvertent outcome, these supposedly psychic children began seeing cosas feas—ugly things, such as the spirits of dead people. When their parents pulled them out of the experiments, Grinberg became distressed. His colleagues, including E. Roy John, began to doubt his techniques and question his findings. “The kinds of tests to which such data should be subjected are well known,” John told Sam Quinones. “He certainly knew what those tests were and never applied them. I don’t think he had a dishonest bone in his body, but he certainly had a lot of wishful thinking.” Grinberg did have his defenders, such as the physicist Amit Goswami, then at the University of Oregon. More typical was the skepticism of Karl Pribram, one of the deans of American neuroscience. “If it’s true what he was finding,” Pribram said after twice visiting Grinberg’s lab at UNAM, “it could be very, very important. But I think that his work needs a lot of confirmation and testing in other laboratories.”

Grinberg was restless. He was attracted by rational thinking, but he also believed that reason was an impediment in epistemological endeavors involving human consciousness. His scientific research was entering new horizons. He began to explore shamanism, widely embraced in Mexico, as well as indigenous practices that had survived centuries of repression. He also studied the Zohar, the influential 13th-century text of Kabbalah, to which he felt drawn “like wood to fire.” Prone to mood swings, Grinberg often consulted curanderos—shaman healers. His students loved him. He was able to procure federal grants. Yet his peers, perplexed by his refusal to allow scholars to corroborate his findings—and by his refusal to allow the students who worked in his lab to speak to others—continued to find his investigations suspect.

IV

My opinion of Grinberg changed in 2016. I was on a lecture trip in Colombia when I reluctantly accepted an invitation to participate in a shamanic ceremony. Along with 12 others, I lived for three days at a location in the Amazon to which we were taken in the middle of the night. My recollection of the ceremony has altered in the past seven years. I remember a jungle environment, a corolla of trees, a hacienda surrounded by a large expanse of land, an old brick oven around which most of us congregated in the cold. I had always avoided shamanic experiences, considering them too tumultuous for my taste, and I kept telling myself beforehand: This isn’t for you, Ilan. Just ask to be driven back.

On day one, I ingested ayahuasca. My lifelong devotion to Judaism as well as my hyperrational nature were instantly put in question. Was I seeking a higher plane of spirituality through a hallucinogen? Why surrender my sense of control when, for most of my life, I had been convinced that the divine was an abstraction and that only through the mind, through intellectual elucidation, could we reach heightened levels of consciousness? Everyone around me also drank the potion, which was dark and gooey. Their behavior quickly became erratic. Some started jumping frantically, hitting themselves against the oven wall, lying down on the ground and pretending to be dead. Others started to vomit, screaming without end, their eyes rolling feverishly. It felt as if I had been transported into a lunatic asylum.

For a long while, the ayahuasca did not have an effect on me, but once it did, I was in another dimension. I underwent an anatomic metamorphosis. First, I lost my sight, as if someone had stolen my eyes. Then I became a jaguar. Still later, my body, ceasing to be a cohesive unit, became a cloud of atoms dancing to their own rhythms. I traveled through space, flying over the corolla of trees, unbound by gravity. I also traveled through time. Not so much to another historical era, but cosmically into the oven, in which an intense fire was consuming a pile of logs. Suddenly, I found myself in Auschwitz, where a number of my family members had perished. And I came tête-à-tête with figures from the Talmud, such as Rabbi Akiva and the canonical rabbis Eliezer ben Hyrcanus and Joshua ben Hananiah, who exist in the text through their eternal opposition of views.

By the time I returned home to Massachusetts, I was a different man, starving for existential recalibration. I started to question, for example, the ways I had previously acquired knowledge. Processing what I learned in a strictly rational way now felt simplistic. I became aware of other sensory channels aside from sight, smell, hearing, touch, and taste. My teaching methods also changed: I learned how to listen and be humble, how to process insight not by reason but through every cell of my body. In general, I was more at peace.

Subsequently, I saw Aunt Hilda in Ohio. We talked about diverse things, including her sessions with Heriberto, a shaman who had guided and cleansed her, and from whom she had learned so much about herself. She talked to me now about Grinberg in much more detail. Although she loved him, she said, he had become irascible, unpredictable, an enigma. She didn’t know, furthermore, how to catalog his work. Toward the end of his life, he had stopped talking to her (because she had dedicated her master’s thesis to someone else), but she kept him in her heart. She told me about Sam Quinones and his investigation into Grinberg’s disappearance. As it happened, Quinones and I were long-time acquaintances. His profile of Grinberg, published in the July/August 1997 issue of New Age Journal, served as the backbone of Ida Cuéllar’s documentary. Quinones, who appeared on camera a number of times, said that although he found Grinberg intriguing, “the type of science he did—to put it charitably—had been diluted by his extreme beliefs.” For Quinones, Grinberg personified a volcanic mixture of deductive reasoning and an overinflated ego.

V

Grinberg had been attracted to shamanism since his year-long stay in Israel in the early ’60s. Like Kabbalists, shamans are interested in a higher realm of consciousness and in connecting the earthly with the divine. Convinced that the mind was trapped in the human body, Grinberg sought to liberate the mind through meditation, hypnosis, and hallucinations. As he relates time and again in Los chamanes de México, he not only participated in these practices, he also led groups of initiated followers, often in proximity to an established curandero, his preferred approach, but not always. He describes eating mushrooms and using other entheogenic substances. These episodes, though frustratingly lacking in any scientific underpinning, are narrated in an unencumbered way. He specifies the number of participants, the visions they experience, who speaks at a particular time, what the shaman’s overall behavior is, and so on.

According to several talking heads in Cuéllar’s film, in 1975, Grinberg was suddenly invited to Los Pinos, the central building in Mexico City where the Mexican president and his administration operated. Margarita López Portillo—the sister of the nation’s leader, José López Portillo, and a woman known as a flamboyant supporter of indigenous cultures—wanted to get to know him. More important, she wanted him to meet Bárbara Guerrero, the curandera known as Doña Pachita, a cabaret singer and lottery ticket seller who had fought as a young girl in the Mexican Revolution alongside Pancho Villa. Volume three of Los chamanes de México is exclusively devoted to Doña Pachita, whom Grinberg describes as his mentor. Her rituals were nontraditional. Any time the government went after her “for practicing voodoo rites,” she went missing for extended periods of time, as if she had evaporated from the world. In his book, Grinberg accepts at face value Doña Pachita’s assertion that she was the niece of Moctezuma and the sister of Cuauhtémoc, the last of the Aztec emperors. She “was capable,” he writes, “of materializing and dematerializing objects, organs, and tissue.” And he suggests that “by means of the manipulation of organic structures,” Doña Pachita could diagnose and heal people without being physically present. She could even perform organ transplants at will. “She did this with colossal power and accuracy.” As Quinones puts it, Grinberg’s

experiences with Pachita also influenced his scientific thinking. Grinberg came to believe that the neuronal field he had postulated interacted with what he called an “informational matrix,” a complicated concept that his students still have trouble explaining. He believed that experience and perception were created as a result of this interaction, and that the curative powers of shamans and curanderas like Pachita came from their ability to gain access to the informational matrix and change it, thereby affecting reality.

Sometime later, Grinberg became a disciple of another luminary in Mexico’s shamanic constellation: María Sabina, an indigenous Mazatec woman who performed purification rituals using mushrooms. Sabina was from the Sierra Mazateca area in the state of Oaxaca. One humid night at her home, Grinberg ingested mushrooms, intending to chronicle his experiences. But his hallucinations blocked his rational thought. Sabina was near him, chanting, over and over again, San Pablo, San Pablo. At first, he was cold, agitated, uncomfortable. In his mind, he wandered along strange, undulating streets. He then left Sabina’s house in a panic and went onto the road. Soon he was imagining himself in the comfort of his living room, reading quietly on his sofa. Then he returned to Sabina’s side. The hallucinations stopped. He describes all of this in volume one of Los chamanes, thanking María Sabina “for having shown me one of my emotional refuges, my incapacity to live in the present and my tendency to escape reality to seek shelter in a structure of comfort.”

An outcome of these encounters was an experiment Grinberg devised in 1987. It involved two participants who were placed in the same room, with electrodes attached to their heads. Grinberg asked them to attempt telepathic communication. Then, after one of the participants was taken elsewhere, the other was stimulated with sounds and flashes. Grinberg, studying the brain waves of each, immediately recognized a simultaneous reaction in the distant participant. This he named “transferred potential.” Over the next few years, he often repeated the experiment, documenting transferred potential in a quarter of his subjects. As Quinones puts it, Grinberg believed that the results of his experiment “supported his theory of a neuronal field connecting all human minds.”

In several episodes devoted to shamanic followers, Grinberg reaches into Jewish history to make a particular point. There is a section in volume one of Los chamanes called “Los ‘hasidim’ de Morelos” (The Hasidim of Morelos), in which Grinberg describes a shamanic group that performed its mystical rituals just like the 18th-century followers of the Baal Shem Tov—Israel ben Eliezer, the founder and leader of the mystical Hasidic movement. A special class of Hasidic Jews are supposedly able to communicate with nonmaterial entities, which help them cure an assortment of human ailments, physiological and emotional.

Grinberg painted himself as a kind of Mexican Hasid. Aunt Hilda passed on to me one emblematic story. Just like every other observant Jew, Grinberg would fast on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. But rather than attending synagogue to seek a state of introspection, he would travel about 50 kilometers to the highlands north of Mexico City and the ancient archaeological complex of Teotihuacán. In the Nahuatl language, Teotihuacán means “the birthplace of the gods.” The Aztecs built the city from around 400 BCE to around 300 CE, and the Temple of Quetzalcóatl, the Pyramid of the Sun, and the Pyramid of the Moon still rise proudly from its large esplanade. Every year, Grinberg climbed the steep staircase of the Pyramid of the Sun and sat for hours on the promenade at the top, entering a spiritual state. I can picture him now: possibly alone or accompanied by a friend or a student. In Kabbalistic literature, the most austere and inventive of prophets, Ezekiel, describes the revelation of the merkavah, the celestial chariot sent down for him so that he may achieve a mystical union:

I looked, and lo, a stormy wind came sweeping out of the north—a huge cloud and flashing fire, surrounded by a radiance; and in the center of it, in the center of the fire, a gleam as of amber. In the center of it were also the figures of four creatures. And this was their appearance: They had the figures of human beings. However, each had four faces, and each of them had four wings; the legs of each were [fused into] a single rigid leg, and the feet of each were like a single calf’s hoof; and their sparkle was like the luster of burnished bronze.

On Yom Kippur, one of the holiest days of the Jewish calendar, Grinberg felt that he was in direct dialogue with the divine. Then, as sunset approached, he returned to Aunt Hilda’s mother’s house in Mexico City, where, along with the rest of his family, he broke the fast.

VI

Mexico underwent a reckoning in 1994, the year Grinberg went missing. Carlos Salinas de Gortari was president at the time, and on January 1, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with Canada and the United States went into effect. The agreement was sold to the public as the catalyst of a new age in which foreign investment in manufacturing would finally lift many out of poverty, with goods freely flowing across the three countries. But everything went haywire on that New Year’s Day, when the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (EZLN)—known as the Zapatistas, after Emiliano Zapata, the hero of the Mexican Revolution—stormed multiple locations in the southern state of Chiapas, demanding social, economic, and political rights for the indigenous population. Its leader, Subcomandante Marcos, a.k.a. Rafael Sebastián Guillén Vicente, argued that this segment of Mexico’s society was once again being left behind, this time because of NAFTA.

Grinberg was an enthusiastic supporter of the Zapatistas. Throughout 1994, he joined marches in Mexico City, added his signature to public letters, and connected the Zapatista movement to his explorations of shamanic experiences and to alternative studies of the mind. It was about this time that Grinberg drifted further into the realms of impossibility. Might he have suffered a mental breakdown? There is an indication that in the last period of his life, he was overwhelmed by intense paranoia. He said, for example, that he was being followed, that his well-being was always in question. In his last interviews, Grinberg’s grandiose explanations of the mechanics of the universe descended into hyperbole. In his later writings, he depicted himself as a space traveler who wandered through galaxies using telepathic connections. And he offered a survey of different advanced civilizations—traces of which were invisible to the naked eye. He reported being overwhelmed by a supernatural type of love, which led him to the conviction that he had become a deity. He seemed unsettled, possessed by inner demons. Could the regular ingestion of hallucinogenic substances have further detached him from empirical reality? It is useless to speculate. His story is compelling precisely because its threads twist and turn at the end, making it ultimately indecipherable.

In the early ’90s, Grinberg befriended Carlos Castaneda, the Peruvian-born pseudo-ethnographer and author of The Teachings of Don Juan (1968), and many other bestselling New Age books about Don Juan Matus, a shaman in Arizona. (It was The Teachings of Don Juan that I had mentioned to Grinberg on first meeting him all those years ago.) In the past couple of decades, Castaneda’s work has been debunked as fictional, with Matus himself deemed to have been a concoction. Tony Karam, one of Castaneda’s former followers, said that Grinberg and his second wife, María Teresa Mendoza López—who went by Tere—visited Castaneda in 1991. Grinberg admired Castaneda’s studies of peyote and his accomplishments as a versatile chronicler for the New Age generation. Cuéllar’s documentary implies that Castaneda invited Grinberg to leave UNAM and join his fraternity. Grinberg wasn’t a true Castaneda junkie, though, and so he rejected the invitation. The relationship soured. Two years later, Castaneda was in Mexico City. According to Grinberg’s friends and family, he frequently called Castaneda “an egomaniac, more interested in power than truth.” They also recalled how Tere had encouraged Grinberg to reconsider joining Castaneda’s group. Quinones adds: “Students remember her speaking of her friendship with Florinda Donner, an associate of Castaneda’s.” Naturally, there is speculation—once again, quite sensationalist—that Castaneda’s entourage plotted Grinberg’s demise.

During what turned out to be his final days, Grinberg phoned his daughter Estusha to say that he was going to Kathmandu to participate in a series of meditations. If he had a ticket to Nepal, no airline has a record of his using it. Comandante

Clemente Padilla didn’t find any evidence confirming Grinberg’s departure from Mexico. No one saw him in Kathmandu. His siblings organized a birthday party for him on December 12 to which he didn’t show up. He had left voicemails for one of his siblings saying that Tere was persecuting him; the two would often fight as a result of jealousy. According to those I talked to, Tere suffered from bipolar disorder, and her own family didn’t know that she was wedded to Grinberg. Grinberg’s close circle—his brothers, his daughter, his first wife, Aunt Hilda—felt that Tere was an impostor who represented a physical threat, that she was part of a larger coterie with a vested interest in controlling him, for whatever reason. One of his brothers says that Grinberg feared he would be murdered—this was revealed during their final visit together. Quinones notes the argument made by Grinberg’s family and friends that Grinberg wouldn’t have left his job, or his daughter, whom he adored, of his own volition.

What we know from Padilla’s report is the following. After Grinberg’s disappearance, Tere cashed a check for $1,000 from her husband’s book distributor. She reportedly told the watchman at one of their houses in Morelos not to come back to work because her husband had flown to Guadalajara. But a few days later, she notified Grinberg’s stepmother that he was in the state of Campeche and that the couple intended to fly to Nepal when he came back. Telephone calls placed from various locations in Mexico and the United States linked her to a night watchman at a school, a man with a paramilitary background. She was also seen a couple of times with a blond woman, with whom she visited one of the Morelos homes so that she could retrieve her dog, some kitchen utensils, her clothes, and a table. Some months later, she was spotted on Rosarito Beach, south of Tijuana. On Mother’s Day, 1995, she called her mother. Then, María Teresa Mendoza López also disappeared—forever.

VII

In Spanish, the word aparecido isn’t quite the opposite of desaparecido. It is used to refer to a ghost, an apparition. Ever since he dissolved into the ether, Grinberg has been precisely that: a specter people keep invoking for all kinds of reasons. For them, he is proof that death isn’t final, that somehow a person who vanishes hasn’t disappeared but is simply misplaced. He will come back, his followers believe, wiser, with a cure for the blunt rationalism of our age, which blinds us to the mysteries of the universe.

Aunt Hilda and others talk about him with deep affection. They say that a lesson can be learned from his courage. A legend in Jewish tradition suggests that each human generation depends on 36 righteous individuals—Lamed Vavniks—without whom the world would cease to exist. The Lamed Vavniks are unaware of their importance as the pillars of life. They can be ignorant, loquacious, even pretentious. Yet they enjoy mystical powers and embody the divine presence. Grinberg might have been one of them.

To me, he was the embodiment of a dissatisfaction with the status quo. In a Catholic country of more than 125 million people, the Mexican Jewish community is minuscule. To survive, it protects its insularity through a certain disdain for the outside world. Its members to this day choose to be different by connecting themselves to an ancestral culture that spans diasporas. Grinberg rebelled against the community by finding ways to bring together his Judaism with the shamanic teachings he observed in the indigenous communities that he studied. He wanted to believe that everything had a deeper meaning. He was also a dreamer whose dream ate itself up. In those last few months, there doesn’t seem to have been a method to his madness. He was right that reality is unforgiving and that it is full of mysteries. The secret is to know not only how to approach those mysteries but also how to turn them into believable narratives.

Not long ago, I contacted a cousin of mine who happens to be a necromancer. I asked him to find out whether Dr. Jacobo Grinberg Zylberbaum was still alive. Enthusiastic about the assignment, he told me he would need a couple of weeks. It took three, maybe four. When my cousin finally got back to me, he said that he and a group of spiritualists, having performed a series of séances and other rituals, had done everything in their power without success. “Dr. Grinberg is in bardo,” he said, “the Buddhist liminal state between death and rebirth.”

That’s exactly how he lived his life.