The Hedgehog’s Great Escape

A young Frenchwoman who ran the Allies’ most persistent spy group was in the Gestapo’s grasp

The air in the barracks detention cell was hot and sultry—typical July weather for the southern French town of Aix-en-Provence. Not surprisingly, the woman lying on the cot was bathed in sweat. But the reason wasn’t just the stifling heat. It was also fear. A few hours earlier, she had been captured by the Gestapo while combing through intelligence reports from her resistance network. The Germans who had taken her captive knew she was an Allied spy, but they had no idea of her true identity. According to her papers—forged, of course—she was a French housewife named Germaine Pezet. Dour and dowdy, she wore spectacles, was drably dressed, and had lusterless, jet-black hair. It was the latest of her many disguises, this one concocted in part by a dentist in London who had made the dental prosthetic that helped transform her appearance. No outward trace remained of the chic, blond Parisienne she’d been before the war—a woman born to privilege and known for her beauty and glamour. For Marie-Madeleine Fourcade, those prewar years seemed like ancient history. Immediately after the German occupation of France, she’d joined the resistance—part of a “minute elite,” as Kenneth Cohen, a top British intelligence official and close friend of hers, called the comparatively few French men and women who rose up in 1940 to defy the Nazis.

In 1941, at the age of 31, she became la patronne—the boss—of what would emerge as the largest and most important Allied intelligence network in occupied France. Throughout the war, it supplied the British and American high commands with vital German military secrets, including information about troop movements; submarine sailing schedules; fortifications and coastal gun emplacements; and the Reich’s new terror weapons, the V-1 flying bomb and the V-2 rocket.

Over the course of the conflict, Fourcade, the only woman to head a major resistance network in France, commanded some 3,000 agents, who infiltrated every major port and sizable town in the country. They came from all segments of society—military officers, architects, shopkeepers, fishermen, housewives, doctors, artists, students, bus drivers, priests, members of the aristocracy, and France’s most celebrated child actor. Thanks to Fourcade’s determined efforts, almost 20 percent were women—the highest number of any resistance organization in France.

Her group’s formal name was Alliance, but the Gestapo called it Noah’s Ark because its agents used the names of animals and birds as their aliases. Fourcade had come up with the idea and assigned each agent a nom de guerre. Many of the men bore the names of proud and powerful denizens of the animal kingdom: Wolf, Lion, Elephant, Bull, Eagle, to name a few. For her own code name, she decided on Hedgehog.

On the surface, it seemed an odd choice. A beguiling, bright-eyed little animal with prickles all over its body, the hedgehog was—and is—a beloved figure in classic children’s books. In Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, hedgehogs are used as croquet balls by the Queen of Hearts. In Beatrix Potter’s stories about Peter Rabbit, one of her most endearing characters is a hedgehog named Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle, who was based on Potter’s own pet hedgehog. But the hedgehog’s unthreatening appearance is deceiving. When challenged by an enemy, it rolls up in a tight ball, which causes all the spines on its body to point outward. At that point, as a friend of Fourcade’s once noted, it becomes “a tough little animal that even a lion would hesitate to bite.”

Until July 1944, Fourcade had managed to elude her foes, but many others in her network had not been as fortunate. For the previous year and a half, the Gestapo had engaged in a full-scale offensive to wipe out Alliance. Hundreds of her agents had been swept up in wave after wave of arrests and killings; whole sectors had been annihilated. In the summer of 1944, Fourcade had no idea how many of her people were still alive. Dozens, including some of her closest associates, had already been tortured and executed.

After each crackdown, the Gestapo was sure they had destroyed the group. But they had not reckoned with its leader’s resourcefulness and fierce persistence. Every time a regional circuit was decimated, she managed to cobble together a new one.

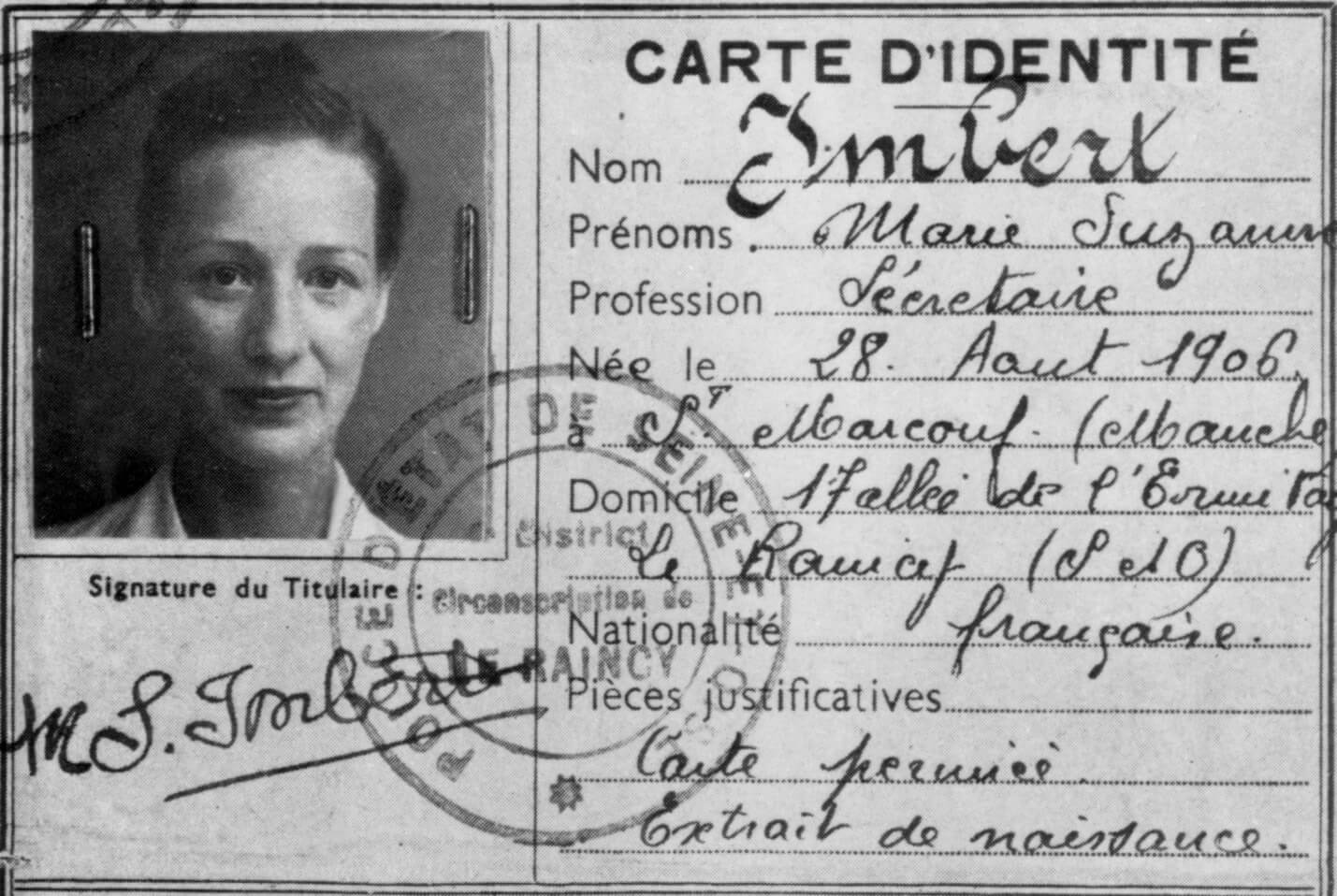

A false identity card used by Fourcade

By July, Helen des Isnards, the scion of a prominent aristocratic family, who headed Alliance’s operations in southeast France, had things well in hand. So Fourcade, after a week in Aix-en-Provence, decided it was time to move on to Paris to help her other beleaguered agents in the north. Georges Lamarque, a brilliant young mathematician who ran an Alliance subnetwork called the Druids, was then in Marseille; he made arrangements to pick her up in Aix on July 17 and escort her to the French capital.

On the afternoon before she was to leave, she stood at an open window in her flat and gazed out at the narrow street below, watching housewives come back from their daily shopping trips for groceries. The day was hot and humid, and the scent of the roses that grew everywhere in the city was particularly intense. Lulled by the peaceful scene and the heat, she was startled by a knock at the door.

When Fourcade opened it and saw des Isnards’ grim expression, her lethargy instantly vanished. He’d just been informed, he said, that the Germans were planning to raid Aix the following morning. They were apparently trying to track down a group of maquis (resistance agents) that had set up camp nearby. He urged her to pack all the reports, and he would take them and her back to his farmhouse. She argued against leaving, noting that the raid wasn’t scheduled until the next day and that he could pick her up early in the morning. When she made clear that further arguments would not change her mind, des Isnards reluctantly agreed.

After closing the door behind him, Fourcade went into the kitchen to get something to eat. Once she’d finished, she returned to the sitting room to tidy it in preparation for her departure. At that moment, she heard a loud crescendo of voices speaking German in the stairwell. Realizing she hadn’t locked her door’s deadbolt after des Isnards’ departure, she rushed to push it into place, to give her time to escape out the back door and into the courtyard. Try as she might, though, she couldn’t resist the force of the men pushing on the door from the other side.

It crashed open, and well over a dozen gun-waving Germans rushed in, all but four of them in gray-green army uniforms. “Where’s the man?” they shouted at Fourcade, a couple of them pushing her back against the wall with their revolvers. Her heart thudding, she replied that no man was there; she was on her own. Then she went on the offensive, just as she had done during a search by the Germans of her Marseille headquarters almost two years before. Why did they think the man was in her apartment? There were plenty of other apartments in the building.

Her play-acting was convincing enough that the leader of the raid, dressed in mufti and clearly Gestapo, ordered all but one soldier to search the entire building. With the lone guard training a machine gun on her, Fourcade wandered around her sitting room, waiting for a chance to move a stack of intelligence reports from the table on which they were piled. When the man turned his head for a moment, she scooped up the papers and pushed them under a divan. Now that the papers were out of sight, she asked the guard to describe the man they were seeking. He was tall and fair, the guard said, and the Gestapo called him Grand Duke. Fourcade’s heart skipped a beat. So the Germans’ quarry wasn’t the maquis. It was des Isnards himself.

After a few minutes, the rest of the raiding party returned, disgruntled over their failure to find the man they were after. They began searching the flat, turning over the mattress in the bedroom, pulling out the contents of the closets, and rummaging through the cupboards, bureaus, and her suitcases. She had wadded up and hidden much of the intelligence material inside two padded footstools in the sitting room, which the Germans ignored. They also had shown no interest in looking under the divan.

As the search continued, Fourcade continued to vigorously protest her innocence. She was a native of Marseille who had come to Aix to get away from the Allied bombing raids of her hometown. The bombs were driving her mad, she said. She hated the war, and all she wanted was a little peace and quiet.

The Gestapo leader told her the man they were looking for was an important member of a terrorist resistance organization called Alliance. They obviously didn’t realize that the head of the network was standing right in front of them.

No, she said, no one answering the man’s description had come to her door. In fact, no one had visited her at all since she’d arrived in Aix. She rambled on and on, continuing her complaints about the bombing and the war and trying to make herself sound as stupid as possible.

Finally, after what felt like an eternity, the leader seemed convinced that she was telling the truth. He ordered her to let him know if she came in contact with the man they were seeking, and when she agreed, he motioned the other members of the raiding party toward the door. As they picked up their guns and headed out, one of them casually glanced under the divan. He looked again, and with a shout, sank to his knees and pulled out a large handful of coded messages on grid paper, holding them up in triumph.

With his discovery, the others went berserk. They ripped open the upholstered furniture in the sitting room and found the papers hidden in the footstools. Several of them advanced menacingly toward Fourcade with their revolvers and machine guns, and for a moment, she was afraid they were going to shoot her on the spot. At that moment, her only thought was that at last her turn had come—like the hundreds of others who had gone before her.

Incandescent with rage, the Gestapo leader violently shook her. “Who are you?” he roared. She replied that she was a spy sent by London to meet some agents in Aix. The man for whom they were searching had indeed come to her door, but she didn’t know who he was. He was simply an emissary who was there to arrange an appointment between her and the operatives she was to meet the following day.

When the German ordered her to give him her real name, she coolly responded that he was far too unimportant for her to deal with. She would speak only to the senior Gestapo officer in the region. The leader snapped an order to a subordinate, who ran off. In a few minutes, he returned and whispered in his boss’s ear. The leader told Fourcade that the senior Gestapo official in Marseille had agreed to come to Aix the following morning to question her. He ordered her to pack a suitcase, then hustled her down the stairs and into a black car that drove off at top speed, two Gestapo men flanking her in the back seat and the leader in the front.

She was taken not to a prison but to an army barracks in the center of Aix, where she was pushed into a punishment cell for soldiers. The several men in the cell were rousted out, the cell’s heavily bolted door closed behind her, and she was left alone in the small, bare space that stank of urine, sweat, and tobacco. She sank down on a cot covered with a filthy gray blanket, and then suddenly felt sick to her stomach and ran to the corner of the room to vomit. Notwithstanding her outward composure in front of the Germans, she was mortally afraid. Exhausted and gasping for breath, she returned to the cot and ordered herself to get some sleep, to be better able to stand up to the ordeal that assuredly would face her the following morning. By then they would have combed through her mail and found out who she was.

Would she be able to remain silent and withstand the beatings and other forms of torture that would follow? She remembered confiding her fears about a Gestapo interrogation to the priest at confession and his response: taking cyanide in such a situation would not be suicide but a necessary way of resisting the enemy.

Fourcade opened her handbag, which had not yet been confiscated by her guards. Perhaps she should take the cyanide now to make sure she would never talk. But then she realized that if she did, the Gestapo would be waiting the following morning for des Isnards to arrive at her flat. He and his operation, the bulwark of Alliance, would be wiped out, and almost certainly the entire network would fall as well. Before she took the irreversible step of suicide, she must explore every possibility of escape.

Feeling faint in the hot, stuffy cell, she walked over to the barred window to get a breath of air. As she stood there, she looked carefully at the window, which was large and had no glass panes. A thick, horizontal wooden board was screwed into the window frame, blocking more than half the opening and leaving a relatively small space at the top to allow in air and a bit of light. There was also a space between the board and the bars covering the window.

Without the right tools, it would be impossible to remove the board and one or more of the bars. But could she possibly slip between the board and the bars and ease her body out? She remembered her father telling her how burglars in Indochina would oil their bodies to squeeze through the bars of the gates and windows of houses they had chosen as targets. Thanks to fear and the stifling heat, her own slight, slender body was slick with sweat. Could she follow their example? She decided to try.

She waited until the guards outside her cell went off duty at about three A.M. Pushing the cot under the window, she picked up a large washbasin, turned it upside down, and put it on the cot. After taking off all her clothes, she climbed onto the basin, a light summer dress clenched between her teeth.

She managed to pull herself up and over the board. With her body tightly pinned between the board and the bars, she began trying to ease her head between the gaps. The first two were far too narrow. The next one was wider, and she thrust her head as hard as she could through the opening. Although extraordinarily painful, the maneuver worked, and her head popped through.

Just then, a German truck convoy lumbering down the street stopped outside the barracks, directly opposite Fourcade’s window. She quickly pulled her head back through the opening, with a pain so fierce she feared her ears had been torn off. It was the Gestapo, she thought. They’d come early, and they would find her pinned like a bug between the wooden board and the bars.

An officer emerged from a staff car and shouted something at a sentry standing in front of the barracks, a few hundred feet away from her window. With a great rush of relief, she realized he was asking for directions. The convoy was not Gestapo, as it turned out, just an ordinary army unit that had gotten lost. Once the sentry responded, the officer got back in the car and the line of trucks disappeared down the street.

After the convoy had gone, she again forced her head through the bars, an effort even more excruciating than before. She squeezed one shoulder through, then her right leg. The most searing pain came when she began easing one of her hips that had been displaced through; as she worked at it, she told herself that torture would be far worse than the agony she was enduring now.

Miraculously she succeeded and found herself out on the ledge, with her dress still gripped between her teeth. As she jumped to the ground, the soft thud of her feet alerted the sentry, who clicked on his flashlight and shouted, “Who’s there?” She lay flat, and the beam of the flashlight passed above her. When the sentry finally turned off the light and moved away, she wrapped her dress around her neck and scuttled on her knees, like a crab, across the street.

On the other side, she jumped up, put on her dress, and stumbled off in the darkness. After a few minutes, she spied a cemetery that was dotted with white family mausoleums, some as big as chapels. There she could hide for a moment and figure out what to do next. She found a crypt with a broken door and crept inside. Sinking down to rest, she examined the damage to her body from the escape: she could feel that her face was bruised and bloodied, and could see that her knees were badly skinned and the soles of her bare feet shredded from running through brambles and on the stony streets.

She knew she couldn’t stay there for more than a few minutes. She had to reach des Isnards’ farm no later than seven, to stop him from going to her flat in Aix and walking into the Gestapo trap. But first she had to thwart the efforts of the German searchers and dogs that would soon be on her trail. Remembering a book she had read as a child about an escaping officer who had eluded search dogs by washing off his scent in a stream, she found a trickle of a creek nearby and bathed her injured face, knees, hands, and feet. As she did so, she tried to remember how to get to des Isnards’ farm.

She was appalled when she realized that to reach the road leading to the farm, she would have to retrace her steps through town, past the barracks from which she had just escaped. And she had to do so as soon as possible. Dawn was breaking, and before long the guards would open the door to her cell and find her missing.

Trembling with fear and pain, she walked back the way she had come. Everything was quiet in the golden early-morning light, and although a few passersby looked at her curiously, the sentry in front of the barracks paid her little heed. But just a few minutes later, as she turned onto the road leading to des Isnards’ farm, she heard in the distance the sounds she had feared: the barking of dogs and the unearthly din of sirens. They had discovered her escape.

Mechanically, she kept walking as she struggled to come up with a way to dodge the roadblock that would soon be set up on this road, as well as on all the others leading out of Aix. She headed into the field that stretched beside the road, where a number of old peasant women were gleaning stray ears of corn left on the ground from the previous harvest. Fourcade joined them, occasionally stooping over and picking up an ear or two. Soon, from the corner of her eye she saw soldiers halting foot and motor traffic on the road and checking papers. None of them paid attention to the women in the field.

Fourcade continued gleaning for a while longer—until the soldiers and roadblock were well in the distance. Back on the road, she finally found des Isnards’ farmhouse. The front door was unlocked, and she limped inside. As she did, she called out the names of des Isnards and his wife. She opened their bedroom door, and they sprang from their bed, their eyes wide with surprise. “I’ve just escaped,” she said. “I’ve saved your lives.”

And then she collapsed.

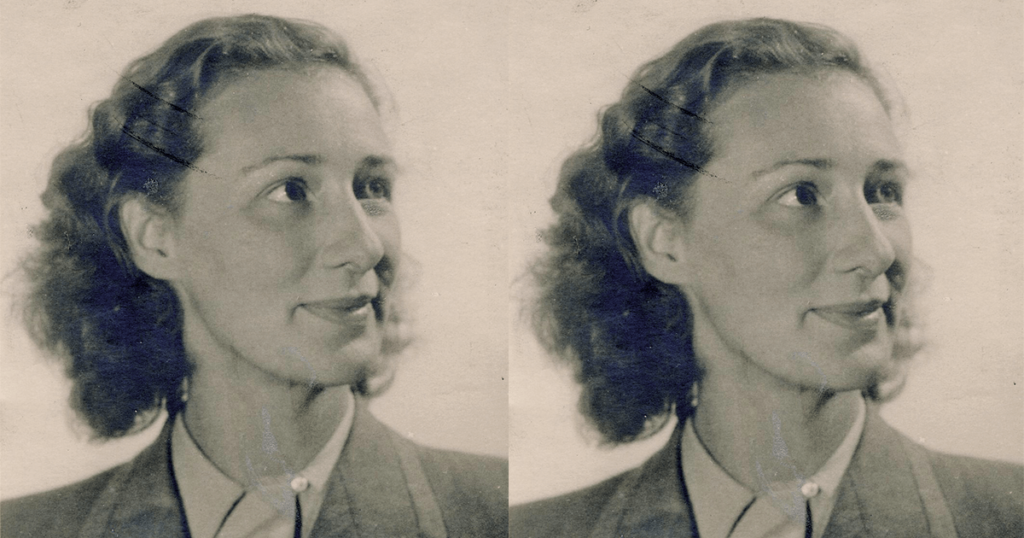

This photograph shows the scrapes and bruises Fourcade received as she squeezed her sweaty body through a tiny opening in the bars of her cell.

After Marie-Madeleine Fourcade’s escape, she made her way to Paris. Just before the city’s liberation in August 1944, she traveled to northeastern France to scout out information about enemy positions for the benefit of U.S. troops heading toward the German border. Fourcade and her network did not finish their mission until the war in Europe ended in May 1945. No other Allied spy organization in France had lasted as long or supplied as much crucial intelligence over the course of the conflict.

Although she survived the war, some 500 of her agents did not. She spent much of the rest of her life fighting for jobs, pensions, and medical care for her fellow network survivors, as well as for the families of those who had died. She also wrote a memoir, entitled Noah’s Ark, which was rightly described by one reviewer as “a Homeric saga” of her and Alliance’s daily life under German occupation. It is the source of many of the details in this story.

When Fourcade died on July 20, 1989, she became the first woman to be given a funeral at Les Invalides, the splendid complex of buildings in Paris that celebrates the military glory of France.