The pandemic that engulfs us has dislocated all of our lives dramatically, often tragically—but for some among us, the obligatory isolation has been a boon for musing. Among the weighty matters I muse upon is my complicated bond to the city of Vienna, a place that I last visited just a year ago, but that owing to the coronavirus, now seems out of reach.

Nature abounds with examples of animals—from butterflies and salmon to storks and eels—that harbor a homing instinct: an urge to return at a certain stage of life to where their lives began. Now, in the 10th decade of my life, I appear to be subject to a related phenomenon, and I find myself engaged anew with my native city, Vienna. Although I lived there for only 15 years before fleeing from the murderous Nazis, the city’s history, its vernacular speech, and its cookery, remain anchored in my consciousness. Countless songs and snatches of poetry that I know from my youth float into my mind these days, and when I am at home alone, I have been known to articulate my feelings aloud in German, and usually, in Viennese.

I recall that as a boy it meant a lot to me that my father’s store was located on the Hoher Markt, the high marketplace, the site where Roman legions had established their camp two millennia ago. In the Middle Ages, the municipal courthouse stood there, and it was where executions took place. Since the early 18th century, the marketplace has been dominated by a huge monument, known as the Vermählungsbrunnen (wedding fountain), which depicts a Jewish high priest as he joins the hands of Mary and Joseph in matrimony. The three figures are surmounted by an ornate high canopy, and the Latin inscription at the base informs us that emperor Leopold I, on whose behest the monument was erected, dedicates it to Joseph—possibly because there were already a great many statues dedicated to his more famous wife.

But I digress. The fact remains that 80 years after I left my native city and entered a rich, full life, Vienna still has a strong pull on me. Fortunately, I have had many opportunities to visit there since the end of WWII. Until the 1970s, Austrians were still mired in their country’s dual identity: of being the first victim of Hitler’s aggression, and of being his avid supporter—circumstances that made my finding rapport with Viennese people problematical. While visiting Vienna with my wife and young children in 1970, we were, by chance, invited to chat with Herr Steinbrecher, who still owned the apartment building that I grew up in, and who still lived there. After a few minutes of chitchat, he turned to me and asked in cultivated Viennese: “Sagens mir bitte, Herr Eisinger, warum haben Sie eigentlich Wien verlassen?” (Tell me please, Mr. Eisinger, just what was the reason that you left Vienna?) I told him that I was a Jew, whereupon he slapped his thigh lightly, saying: Ah so, ah so! Yes, indeed.

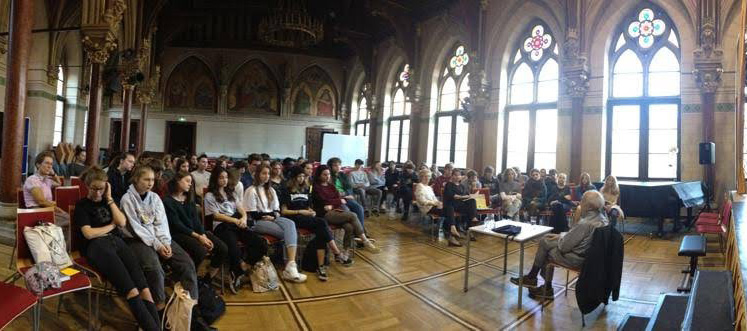

With the passing of generations and the city’s growing prosperity, Vienna became a friendlier place to spend time. A few years ago, when I visited my former high school, the Akademisches Gymnasium, I received an exceedingly warm welcome and was invited to address the students in the Festsaal (assembly hall), and also in their classrooms. I talked about my experiences and answered their questions. The school holds a solemn assembly each year to commemorate the countless victims of the Nazi ideology. Today’s atmosphere in the school could not be more different from that in my school days, when all students were boys and all teachers were dour men—now, largely replaced by strikingly liberated and amicable young women. Recently, I was also pleasantly surprised when the DÖW, the eminent archive that documents Austrian resistance under the Nazis, wished to publish a German translation of my youthful memoir, Flight and Refuge. I was invited to the festive Buchpräsentation in Vienna’s City Library and after I gave a brief talk, I was deeply moved by the enthusiastic reception I was accorded by the audience—mostly young people who must have regarded me as a living fossil. Lengthy reviews of the occasion appeared in the newspapers and on TV, and a few months later, the DÖW announced that it would distribute free copies of my book to all who requested one. They even ordered a second printing in order to fill the demand.

On my recent visits to Vienna, my involvement with the city grew. I now enjoy several new friendships with citizens of what has become a very livable city. On my early visits, a remark of my erstwhile professor, Vienna-born “Vicki” Weisskopf, had often come to mind: it is the fate of a European that no matter which side of the Atlantic he is on, he longs to be on the other side. Later, however, I could enjoy my strolls through the old neighborhood, and they provided me with a reality check of my checkered life. The Reisnerstrasse and the blocks around it have changed little, though they are more affluent. The grocer down the street from my house is gone, as is the Molkerei (where you bought milk, taking your own container to be filled), and the only neighborhood shop that has survived is the Tabak Trafik in the Neulinggasse. My old Volksschule appears untouched, but it no longer has separate classes for girls and boys.

It is not known what draws eels and butterflies back to the places where they were born, but in my case it is at least in part the food that I grew up with. Consequently, my visits to Vienna are not complete without stopping at the Buffet Trzesniewski for a few of their inimitable sandwiches, accompanied by a 1/8-liter glass of beer, known as a Pfiff (a whistle). I also never miss having a dish of Beuschel und Knödel (lung ragout with dumplings) at the venerable bistro Zu den 3 Hacken (3 Hoes), where Beethoven and Schubert once dined.

The true focus of my wanderings through the city is, however, the Stadtpark, Vienna’s first public park, located in what remains of the glacis that adjoined the old city wall. It is just two blocks from my former home, and I passed through every day on my way to school or to my father’s shop. The park harbors many monuments of famous or largely forgotten persons, and the river Wien runs through it. Once prone to disastrous flooding, it now dribbles in a wide channel, bordered by walkways with art nouveau stone decorations. I always end up at the Wetteruhr (weather clock), a civic monument that harks back to the late 19th century, when such public shrines provided citizens not only with the right time, but also with meteorological information. As children, my sister and I visited the Wetteruhr almost daily. We measured our progress toward adulthood by how many of the steps leading to its balustrade we were able to jump down from. The marble top of the balustrade is engraved with lines showing the directions to important cities, from New York to St. Petersburg, and inspecting them as boy made me feel that I was at the center of the world!

When I visited the Stadtpark last summer, I was happily accompanied by my daughter Alison, and as I usually do, I looked for a vacant park bench near the Wetteruhr, in order to make a quick sketch of it. An impish little girl was silently playing on its steps, and her mother was kind enough to photograph the three of us, as I savored the gentle flow of time.