The Heathen School: A Story of Hope and Betrayal in the Age of the Early Republic, by John Demos, Knopf, 352 pp., $30

Cornwall, a small community in northwestern Connecticut, would seem to have been an unlikely place to launch a campaign to save the world. But as John Demos recounts in this wonderfully crafted, deeply disturbing narrative, that is precisely what happened during the early decades of the 19th century. A group of highly educated Protestant ministers, energized by the evangelical fervor of the Second Great Awakening, devised a bold plan to bring true religion to millions of people who had not yet heard the word of Christ. Such ambition had a long and depressing history. The first Europeans who landed in the New World strove to convert the Native Americans, and even though these efforts seldom fulfilled the missionary dream, generation after generation insisted on trying to rescue the heathens from ignorance and evil.

Converting native peoples always turned out to be harder than the evangelicals anticipated. Before the heathens could become proper Christians, they had to learn the ways of civilized society, which in practice meant adopting European customs. The ministers reasoned that if they could just persuade the heathens to speak English, dress in English clothes, and live in English-style houses, they would be more receptive to Christianity. This was a one-sided conversation, of course, driven by a conviction of European superiority, and when the objects of missionary zeal resisted, they discovered that racism and violence visited those who refused to be saved.

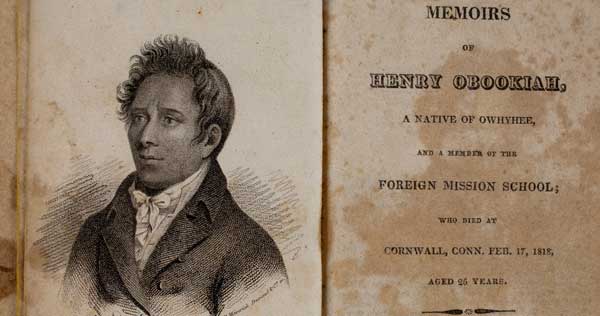

The Mission School in Cornwall hoped to provide bright young men from foreign cultures with a civilizing environment. Only after they had undergone thorough re-education could they return to Hawaii, China, or the American frontier, where they would help their people discover the path to redemption. During the early days, the seminary had a stroke of good luck. One of the first students to arrive in Cornwall, in 1817, was Henry Obookiah, a remarkable man from Hawaii. His intelligence and integrity impressed the school’s supporters, and he served as a model for the entire enterprise. If this heathen could learn so much so quickly, then other, equally promising boys could surely follow in his footsteps.

The banner year was 1818. The Mission School had no problem recruiting students, the majority of them Native Americans. As one Connecticut newspaper exclaimed, “We rejoice to learn that in this state there is … a Seminary for the education of heathen youth, at which there are twelve of this description from different counties.” People throughout the United States contributed money; leading Protestant ministers praised the good work being done at Cornwall. Even though Obookiah died of pneumonia in 1818, before he could bring Christianity to Hawaii, the evangelical community remained optimistic. After all, as one commentator noted, “The experiment has been tried, and has proved successful. Heathen youth can be civilized, and instructed, and prepared for extensive usefulness among their countrymen within a limited period and a comparative small expense.”

But as we learn in this splendid reconstruction of everyday life at the school, the sanguine rhetoric masked deep problems that would in time bring down the entire institution. Enthusiasm outran practical considerations. Ignorance and naïveté encouraged the sponsors to overreach. The curriculum would have been extremely difficult for any young American, but for young men who had recently been torn from their native cultures and who brought only a smattering of English to Cornwall, the challenge of acquiring full English literacy proved overwhelming. Many boys simply gave up. Others showed no interest in their studies. Indeed, only a few students experienced full conversion. All of these things might in time have brought down the school. What did the most damage, however, was love. As one observer declared, “Among all who came to the school from strange lands, the little heathen Cupid, entering uninvited, was the mischief-maker.”

The source of the trouble hardly warranted the public’s hyperbolic reaction. John Ridge, a brilliant student who would become a leader of the Cherokee Nation, fell in love with Sarah Bird Northrup, the daughter of the school’s steward, and she with him. The relationship shocked the missionary community; the girl’s friends shunned her. In the face of extraordinary community pressure, neither John nor Sarah retreated. People throughout Connecticut demanded to know why the school had allowed this affair to develop. After all, she was a white woman, and he a Native American, which meant a person of color. The desire to convert the heathen, to save the world, quickly gave way to racist vitriol. The editor of a Connecticut newspaper reminded readers of “the affliction, mortification, and disgrace, of the young woman [who] … throwing herself into the arms of an Indian … has thus made herself a squaw.” There was talk of vigilantes destroying the school buildings. One self-appointed defender of Christian virtue declared, “the girl ought to be publicly whipped, the Indian hung, and the mother drown’d.”

Then, a short time later, another Cherokee student, Elias Boudinot, announced his intention to marry Harriett Gold, a member of a respected local family. Like Sarah, Harriett insisted that love trumped race, and both couples were properly married before moving to Georgia, then the heart of the Cherokee Nation. The mission board found the whole episode disgraceful. Claiming to speak in the name of “the Christian public universally,” the group labeled their courtship and marriage as “criminal; as offering an insult to the known feelings of the Christian community.”

Then, a short time later, another Cherokee student, Elias Boudinot, announced his intention to marry Harriett Gold, a member of a respected local family. Like Sarah, Harriett insisted that love trumped race, and both couples were properly married before moving to Georgia, then the heart of the Cherokee Nation. The mission board found the whole episode disgraceful. Claiming to speak in the name of “the Christian public universally,” the group labeled their courtship and marriage as “criminal; as offering an insult to the known feelings of the Christian community.”

The school closed in 1826. The evangelical community decided that it was safer to send white missionaries to the heathens than to bring the heathens to the Christians. Demos, whose prize-winning The Unredeemed Captive (1994) explored the complex relation between race and love, describes what happened at Cornwall as a story of “high hopes, valiant effort, leading to eventual tragic defeat.” For all their righteousness, the ministers who wanted to save the world never considered how the so-called heathens perceived the exchange. Who, after all, complained when white men seduced Indian women? For the Native Americans, the fulminations of the missionaries served only as a confirmation of prejudice. “In vain,” an Indian wrote in 1829, “have I looked for the Christian to take me by the hand and bid me welcome … and if they did, it was only to satisfy curiosity and not to look upon me as a man.” After almost two centuries, it is not clear how far we have come from the failed experiment at Cornwall.