When my father died a few years ago, I brought several boxes of LPs back home with me from Florida. My mother was downsizing, and in any case, their turntable had long since broken down. Each of those albums, I realized, as I added them to my shelves, played an important part in my musical education, but two had special significance. These also happened to be the first records my parents acquired upon moving to this country from India in the late 1960s: performances of the Beethoven and Brahms Violin Concertos by the French violinist Christian Ferras, with Herbert von Karajan conducting the Berlin Philharmonic. I cannot count how many versions of those seminal works I have heard over the years, but Ferras’s interpretations are the ones I return to. They are the standards by which I judge all others.

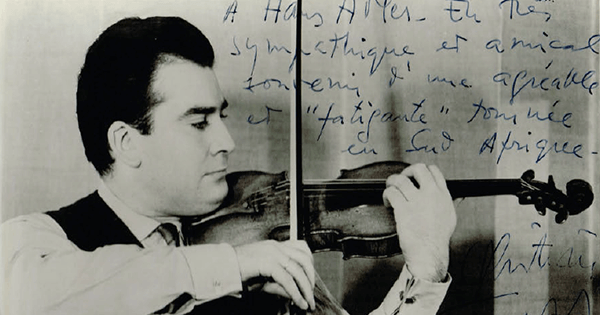

That Ferras, one of the leading exponents of the French violin school, isn’t as widely known as he ought to be seems a bitter shame. Born in 1933, he exhibited a prodigious talent as a child, studying with George Enescu and eventually coming to the attention of the leading conductors of his day. His discography—covering the Baroque era, the great Romantic concertos, the extensive sonata literature (which he traversed with the pianist Pierre Barbizet, his friend and compatriot, with whom he formed a wonderful, symbiotic relationship), and the music of his own time (including the haunting Alban Berg Violin Concerto)—can stand with anyone’s. He was a soulful, intelligent artist who produced a sound that was patrician and elegant, sumptuous and golden, but earthy, too. He also had what all the great violinists of an earlier age had: the quality of inimitability, each performance marked with a musical thumbprint, unique and recognizable. Put on a Ferras recording, and there’s no mistaking that rapid, intense vibrato or his distinctive portamenti (the expressive slides from note to note). Indeed, he could convey a whole palette of tone color in the way he connected just two notes, with a rich and fleshy slide down one inch of the fingerboard.

One Ferras performance will always stay with me: a live recording of the notoriously difficult Sibelius Violin Concerto—filmed on May 26, 1965 and released on DVD some years ago. (A bonus: the chance to glimpse an impossibly young looking Zubin Mehta, then only 29, leading the Orchestre National de l’ORTF of Paris.) It is as close to an ideal interpretation of this work as I could ever hope for, majestic and committed, exhilarating, brooding, poetic, more daring than the version Ferras recorded with Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic, roughly around the same time.

Sibelius composed his concerto in between debilitating alcoholic binges, his marriage frayed, his finances in shambles, and in the second movement, the movement marked adagio di molto—some eight minutes of pure longing and heartbreak ending in a climax of almost indescribable sadness—we sense something of the composer’s despair. It is during this movement, as well, that Ferras will break your heart.

During the pyrotechnics of the previous movement, Ferras had assumed an almost statuesque pose, his head perpendicular to the violin. But as he begins the long, impassioned line of the adagio, he turns his head so that his left cheek is pressed against the violin’s chinrest—an intimate, introspective posture that allows for greater communion with the instrument. As Ferras now plays his slow, sorrowful lines, his tone rich and robust, each phrase turned with such elegance, he seems in the depths of this great lament. The music unfolds with increasing angst, and when the orchestra takes over, we hear storm clouds gathering—a deep rumbling, increasing darkness. The momentum builds via a series of rises and falls. The violin line soars, with sharp trills on the E string, and just when the tension seems unbearable, it dissipates. Yet the feeling of unease returns, now in a sequence of ascending broken octaves, Ferras’s bow rocking back and forth across the strings like a boat upon unsteady waters. A passage of double stops (that is, two notes played simultaneously) then leads to that shattering climax. The movement ends with the soloist hushed and withdrawn, and the camera pans in on Ferras, a tight crop, his face filling the television screen. His eyes are closed, his cheek still pressed against the chinrest of the violin, as he plays his final, whispered utterances. Here, just before the resolution of the cadence—an awful, beautiful moment—something extraordinary happens: tears start streaming out of Ferras’s shut eyelids, rolling quickly down his cheeks.

When I watch this, over and over again, I feel a purifying, cathartic sadness, but also the deepest envy. To be immersed so completely in a work of art, to be moved to tears in the act of its creation—just once I would like to know what that feels like.

But we are rarely privy to the whole story with any artist. For Ferras, the agony was all too real. He suffered, for many years, from acute depression, his illness—and the alcoholism that accompanied it—so severe that he had no choice but to abandon his concert career. After a hiatus of seven years, he attempted a comeback, but it was not to be. In Paris, on September 14, 1982, not 20 years after this wondrous performance of the Sibelius Violin Concerto, Christian Ferras took his own life.