Gray early morning light seeping through the window bars, my thin blanket barely keeping away the chill of another dawn. I can hear The Guard, an early riser, moving around, whistling to his Alsatian: a vicious brute that growls at me and all other black men, having acquired but not lost its master’s biases. How I hate the Island and wonder, not for the first time, if I will live long enough to be free of this place. The Guard kicks hard at my door, jolting me out of the last moments of sleep. In spite of myself, I feel adrenaline flood my body.

“Maak gou,” he shouts. “We don’t have all blerrie day, you lazy skelm.”

His is a voice that cannot speak quietly; nothing less than a bellow would be satisfactory to this bull-like man. But I am grateful to him. Without his prodding, I would get no exercise at all, just grow into an old fat lag, squinting into the harsh light and lime dust of Robben Island. Today, however, I am going to punish him for this rude interruption to my sleep.

I dress quickly and lace up my running shoes, jog outside, my breath billowing steam in the dawn air. The Guard is waiting for me, shifting from one foot to another.

“10K this morning,” I tell him. “And I’m setting the pace.”

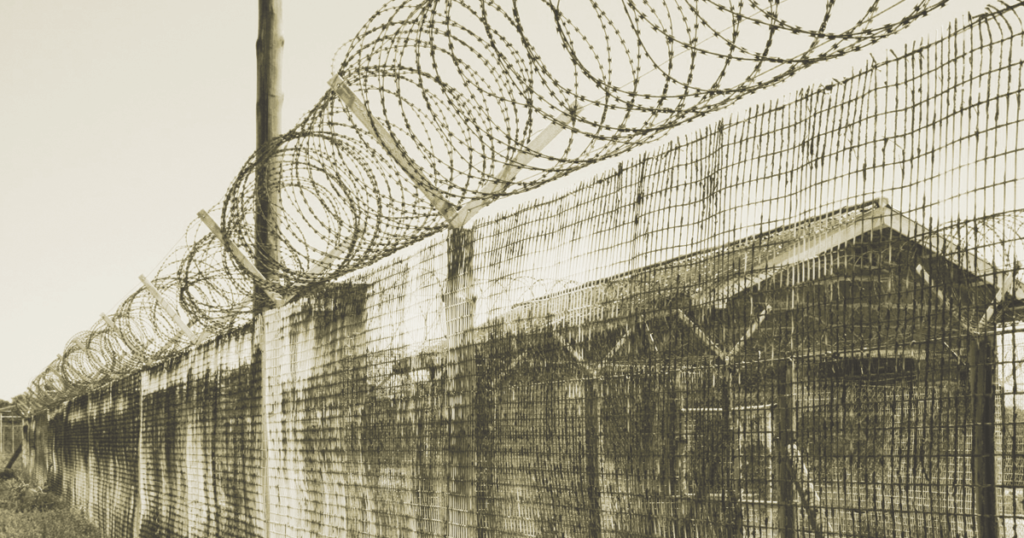

We take off at a good clip, leaving behind the old guards’ barracks where I share a cottage with him, since both our families stayed on in Cape Town. We jog past the prison gate with the inscription “We serve with pride,” then out toward the penguin rookery near the harbor, muscles beginning to warm inside our tracksuits as we settle into our strides. We will cover the whole island several times and be back in about 45 minutes, ready for a hearty breakfast and then showered and dressed well before the first tourists arrive.

I was 19 when I first arrived on the Island, one of the youngest prisoners to be sent here, and I will never forget the way my heart fell when I first looked across the last brief stretch of gray roiling water between the ferry and my place of incarceration. I had been caught with “the goods”—a box of dynamite that had sat moldering for 20 years and was dangerously unstable, stolen from the railroads by the man who betrayed me. He was already working for the police when he persuaded me to store the explosives we planned to use to blow up a power station. The police who staged the dawn raid on my little Soweto hut just laughed when I told them I had no idea what was in the box. “Don’t play the fool,” one said, cuffing me hard on the temple. “We have you on tape talking about your sabotage plans.”

The Guard took a special interest in me from the day of my arrival. Perhaps it was because we were close to the same age—he was the younger brother of a long-time guard, a new recruit into a life of dominating and watching over his fellow man. “You’re mine now,” he told me that first morning in his guttural Afrikaans, thrusting a farm-boy’s massive, rock-hard fist a quarter inch below my nose. “You’re never going to leave the Island.”

He seemed to delight in catching me walking too slowly or pausing at the hard labor we were forced to undergo. At first I hated him as he hated me; he became the human face to my misery and imprisonment. But, over the years, I got used to him … to his loud voice, his shoves when my chained shuffle was slower than he deemed fit, his frequent loud nose-blowing because he’d acquired a permanent allergy to the lime dust that was ruining the health of all of us, prisoner and warden alike. His name was van Tonder, but we prisoners called him uMninawa, “younger brother,” to distinguish him from his older sibling, Sergeant van Tonder.

At the close of one long day breaking rocks at the north end of the island, I sat down to watch several storm petrels struggling against the wind above the sparkling ocean, the long rays of the disappearing sun coloring the foamy tops of the waves a bright maroon. I suddenly felt a looming presence and tightened my muscles for the expected blow and screams of outrage at my laziness, but instead he squatted at my side and gazed out at the view that had drawn my attention.

“Heerlik!” The word was more drawn out of him than expressed. And, yes, the sight was glorious.

“The island is beautiful …” I ventured to say. And then, “But the prison is ugly.”

“Yes. But it is supposed to be that way. To make you understand that you are being punished for your crimes.”

“And what is it that you look at every day?” I asked him.

He looked nonplussed for a moment, and then he stood up and nudged me with his boot, none too gently. “Up!” he commanded in his stentorian voice. “We have no more time for laziness.”

I like to think that something changed in him that day, but it was several months of a shift in demeanor that took place so slowly that at first I did not notice. Then, one day, I realized that I was being chosen for work in the distant, wilder parts of the island, being allowed more time to just take in my surroundings. Van Tonder was always there, and gradually he confided in me that he loved being out in the country, that he had wanted to be a game ranger when he was a child but the prison job had come up, and besides, these days you needed university training to work in the game reserve. He was not the only guard whose attitude was undergoing a shift; you heard less shouting, and it was becoming a rarity that a warden raised a hand to a prisoner.

Then came that wonderful day when I was told that my sentence had been reduced to time served, and I packed my few belongings, was processed out and driven with a double handful of other prisoners to the dock. Aboard the ferry to Cape Town, I did not even bother looking back at the place where my youth had drained into the rock and hard soil of the Island, where I had sat longingly gazing at the lights of Cape Town, imagining the pleasures enjoyed by those lucky enough to live there. At first I was a little bewildered by the noise and bustle of the city. Several times I almost got run down by the cars that streamed too fast everywhere. I ran wild for about a year, drinking too much, getting into fights, trying to make up for the years of confinement and the loss of my youth. And then I met Nomzamo, and soon she was pregnant with my child, and I knew I had to settle down and start providing for my family. But I was not the only one searching for work in a city flooded with migrants from the countryside—after the hated Influx Control laws were lifted—and from all over the African continent. What jobs could I expect with no work history, not even my matric or high school equivalent? For mine was the generation that had brought the system to a halt by making the country ungovernable, the schools unteachable.

I was fortunate enough to land a job, through a cousin, as a parking attendant at a strip mall of fancy shops just outside of Cape Town. We lived with Nomzamo’s parents in a single-room shack in Cape Flats, and six days a week I would commute by bus or kwela to the mini-mall, where I would don a yellow reflective vest and run up and down all day directing cars into the narrow spaces, my pay the two- or five-rand coins the more fortunate—the drivers of BMWs and VWs and Mercedeses—would slip into my proffered hands after they had returned with their purchases and backed out, ready to go on to their next destination. Nomzamo worked part-time as a maid in a house in Greenpoint—Indians, not even whites—while her mother looked after our son, Sipho, “the gift.” But still we made barely enough for food and to help with the rent, not enough to send our bright child to the kind of school he needed.

When I could, on my days off, I would go to the employment office to see if there was anything better available to me. On this one occasion, the young counselor was clearly more interested in the workings of his mobile phone than in me, the humble supplicant before him, even though he would not have had his comfort, his freedom from fear, without people like me. So when he asked me if I had any higher education, I responded sarcastically: “I’m a graduate of Mandela University. Eight years of hard study … so what is that the equivalent of? A master’s? A PhD?”

He looked at me with a gleam of respect. “You were on the Island?”

I nodded.

He began to rummage through some papers on his desk, then looked up with a smile. “This may be your lucky day. You see, one of the honorable ministers went to visit the island, and he was very distressed that his guide was not a former prisoner, nothing to do with the old days. So there’s been a big shakeup, and they’re looking for former prisoners, anyone who was there.”

He saw me hesitating, formulating my reply, and he hastily continued: “The job pays well, very well. And there are government benefits that come with it.”

I sat back, thinking of our overcrowded shack, of my son’s bright smile.

“But …” he hesitated. “Something I’m supposed to ask. You’re not … angry? Bitter?”

There was so much I could say to this, I had trouble formulating the words. And that was a good thing, for it gave me time to think of school fees and what it would be like for my wife and me to have privacy together. Of course the tourists don’t want to hear about anyone’s anger. They want to hear talk of how well the Rainbow Nation is working, a great thing, all the different many-colored birds singing joyfully in unison.

“No,” I said. “Not bitter at all.”

Who did I see that first boat ride back to the place I had sworn never to set foot on again, but The Guard. Spying me, he came rushing forward to pump my hand like we were old maties, the best of friends.

“You, too,” he kept saying. “You, too!”

We jog past the old lighthouse, past Robert Sobukwe’s hut, and then we are back at the guards’ barracks. I shower first, while van Tonder cools down. He is bulkier than I am, and he finds these runs harder. While I soap off, I think about how I tried at first to commute between Cape Town and the Island, taking the first boat out and the last boat back, how burdensome that became. Then my former nemesis and I talked it over and decided to share a cottage, allowing both of our families to stay across the water and enjoy the fruits of our earnings.

We spend the rest of our day taking successive groups of tourists around: to the lime quarries and the cave that became “Mandela University,” to the cracked concrete exercise yard, to that special cell—number 5 in section B—where each visitor is afforded a brief glimpse through the bars at the neatly folded blanket on the narrow bed, the tin-bucket toilet, the tiny enclosure that held that great man. I marvel at how the tourists are from every nation on the earth, how this place, my Island, has become one of the most popular destinations in all of Africa, how reverently they look at all that I point out to them.

At the end of the day, we wind up in the communal dining cell, The Guard’s tourists and mine, and together, trading places like tag-team wrestlers, we tell our stories. It always ends with van Tonder relating how he had told me that this place must be as ugly as possible, to teach the prisoners a lesson for daring to defy the authority of his people. And how I had replied, “And what is it that you look at every day?” In that moment, with the late-afternoon sunlight falling through the high window bars to light up patches of the cell and throw others in shadow, the tourists look at me and see what I mean.