The Last Naturalist

A zoologist happiest in the fields and streams of Ohio wrote major works about the state’s birds and fishes

“The fact which interests us most,” wrote Henry David Thoreau, having paddled a pair of rivers and pondered countless facts on a week’s canoe trip, “is the life of the naturalist. The purest science is still biographical.”

Writing in the 1840s, he would have meant the American naturalist of the hundred-odd years just past: the lone and footloose observer, the collector, the explorer who set out to catalog the wild contents of the new continent. A soloist, let’s say, in the symphonic exertions of science, without whose work we could not today have known what too soon was gone, wiped out, from that primal world. A scientist first, the naturalist emerges also as a romantic figure, contending with heat and cold, hunger, claw and venom—not to mention, early on, encountering justly wary groups of Native Americans, not always to mutual advantage.

Here, then, was an intellect, a literary worker, often an artist with pen or paint, a kind of scientist who by the late 19th century—or the early 20th, depending on how rigorously you define the type—had almost ceased to exist.

Almost.

The night starts out normally enough. The setting, the southernmost of a string of islands in Lake Erie, may seem a bit out of the way unless you’re a bird or a fish. Still, it’s a normal starry night, calm, quarter moon, in May 1954.

A lean, intense islander by the name of Milton B. Trautman—named for the sightless poet, an irony of colossal proportions—has spent the morning at work on his magnum opus, a book about fishes, and the afternoon in his garden sowing cucumbers, tomatoes, and squash. During the day, he has kept an eye, too, on the birds, noting in his journal, “Marvelous conditions for migration high in air.”

At 9:30, the darkness over South Bass Island is split by the sudden spotlighting of an enormous Doric column, an effect like a 350-foot fluorescent tube set on end. The illumination feels no less fierce than Oliver Hazard Perry’s set-to with the British in the War of 1812, which the monument commemorates. Minutes later, Trautman wheels up on his bicycle, swinging an empty sack. Already a feathered rain is falling: migrant birds by the dozen, dazzled by the glare and collided with the column, pelting down. Into the sack goes the night’s sad toll as Trautman pleads with the caretaker to shut the damn lights off. This is done, but not before Trautman, for his trouble, is hit smack on the head by one last casualty.

Back home at his kitchen table, he shakes out the sack, 40 birds, 17 species, most of which he’ll make into museum skins, against some far-off day when it might be doubted that such avian glory ever lived on a dilapidated planet. Remembering then that final fallen bird, he feels in the pocket where he stashed it and fishes it out. Yellow breast, gray back, streaked sides: a sublime rarity on a spring night, a female Kirtland’s warbler.

In 1954, fewer than 500 Kirtland’s warblers survive, wintering in the Bahamas and nesting in Michigan. Seldom are they seen in migration. Surely no other Homo sapiens has ever been hit on the head, or ever will be, by a Kirtland’s warbler fallen from the sky. The spheres seem well pleased with Milton Trautman.

“Kirtland skin lovely,” he records, “one of the best I ever made.”

Four years later, and a year after the publication of his landmark work, The Fishes of Ohio, I first met Milton Trautman. I was 12, and my father and I, hungry after a morning’s fishing, were about to enter a busy lunchroom when its door burst open, liberating a rawboned man of resolute look. Out he strode, donning his hat, a fedora at noonday. My father not only knew him but had written, for the fish book, the bio of the author. The encounter seemed a rara avis come down to crown me. The thing was, I had gotten hold of the book, my father’s copy with a thank-you inscribed in Trautman’s old-timey hand, and read all 683 pages, hardly coming up for air, a feat my father did not omit now to mention.

Trautman must have made some amused remark about meeting his youngest reader. I missed the import but caught the peculiar quality of his voice, not quite singsong but poetic in pattern, and just short of soprano. Deepening the oddity were big ears made bigger by a baldish head, and a beaked nose with a pair of wire-rimmed glasses. He was birdlike, a heron watchful of the shallows about him.

There was that. But I felt almost as if The Fishes of Ohio had been handed down from heaven, and here before me was a certified saint. Fooling around in the outdoors was half my life, reading the other half. I would lay the book open on my bed like a hymnal and luxuriate in its descriptions of shiners, dace, bass, suckers, and carp while a roué named Dr. Bop spun larval rock ’n’ roll on the radio.

It titillated me to think that below the murky surface of our lakes and streams lurked 172 species of fish, potential takers of my home-tied flies. Not the least mystical feature of the book was its distribution maps, one per species, dotted to show collection sites on the very waters I frequented with my father. I pored over every page, the intimate evocations of habitat, the odes to stream gradient and the Allegheny Front escarpment, even the keys to identification, with their arcane allusions to gill arches and scale counts along the lateral line.

Not about to be missed, then, was the book’s foreword, though it seemed a bit oblique. This was written by Carl L. Hubbs of the University of California, whom I myself, in my mental associations with the state, didn’t know from Walt Disney. Hubbs, I learned, was a noted ichthyologist; he praised Trautman’s genius in this “grand volume,” but first, and more boldly, he floated the idea that Trautman might be “the last of the naturalists.” What he meant by this he didn’t say exactly, not defining naturalist, and in any case, he backed off, allowing that “the tribe lives on.” Perhaps he feared stepping on the toes of any aspirants to the title. “Long live such naturalists as Milton B. Trautman,” he concluded, and it’s a nice thought, but he left no doubt that Trautman stood alone.

Still, what was a naturalist? If it was someone, as I supposed, who knew birds and bugs and the names of any number of them, wasn’t I one myself? I had read Margaret and John Kieran’s biography of Audubon, a known naturalist, who as a boy swanned around in woods and fields, taking in the organic sights: that was me.

In that minor key there will always be naturalists, which is only to say there will always be nature, at least of a sort, if not nature as we know it. Picture the microbe-to-hominid tree of life sawed to a stump, sending out an occasional wan shoot. But Hubbs would have been thinking of bigger fish: the sort of naturalist, or Naturalist with a capital N, who prevailed in the hundred or so years when North America was still the field of dreams, lush and without limit. “Last of the naturalists” suggests a line of succession. It means a mythos.

How strange it is that Emerson, in his Representative Men, celebrated the Philosopher, the Poet, the Mystic, the Skeptic, and more, but left the Naturalist out. Here was a rover, a self-reliant individual, an intellect who focused on what was newest in the New World, a fauna and flora apart from the European. The naturalist was an avatar, raw as dawn, of the Emersonian virtues, an idealist’s ideal.

Nearly to a fault, the early naturalist owned the small boy’s instinct to collect specimens. These landed in museums in America and abroad, in the cabinets of paying collectors, or in simple window light as subjects to draw or describe for science. The naturalist was a literary creature: a writer of field notes and journals, whole natural histories, and letters to other workers, even to Carl Linnaeus, who in Sweden cataloged, binomially, the American novelties he was sent.

Some naturalists were artists, hawking prints of birds and mammals and flowers to well-heeled subscribers, but these same depictions, precamera, served the needs of science. Among the popular naturalist-painters were Charles Peale and his aptly named son, Titian; others, including Audubon, Mark Catesby, Alexander Wilson, and William Bartram, not only painted but also produced important writings, at once scientific and literary. Bartram, in the florid but factual prose of his Travels, narrated his explorations in the exotic Southeast—a book that so caught the fancy of Samuel Taylor Coleridge that he bought several copies, thought to have played a part in inspiring his visionary poem “Kubla Khan.”

Naturalist, affirms the OED, is a “less precise term than zoologist, botanist, etc.” Constantine Samuel Rafinesque, flighty enough to smash Audubon’s valuable Cremona violin while flailing it to collect a bat, wrote brilliant (if erratic) works in ichthyology, botany, geology, and taxonomy; Meriwether Lewis, on his expedition with William Clark, described some 300 new species of birds, fish, mammals, and plants. Poles-apart characters, Rafinesque and Lewis, yet in the breadth of their studies they typified the “tribe.” The naturalist was a generalist.

To note that we live in an age of specialization—in the sciences and humanities and in everything, even in our varieties of self-regard—is no revelation. Nonetheless, at Ohio State in the ’60s, when I was majoring in zoology, a lot of us didn’t yet take this lying down. We wanted to look at everything, and not in a lab. The field—as in field naturalist—beckoned, and all that was in it. The jest, truer than not, was that the chairman of the department had made a career out of studying the bacteria that lived on the legs of mites.

It was possible to imagine we might ditch the paradigm because there on campus was our exemplar, Trautman. We glimpsed him crossing the Oval, unbent, bucking the winter winds. “All mythology opens with demigods,” as Emerson wrote in Representative Men. That was it: we, or I anyway, had something empyrean in view.

On completing the fish book, Trautman had moved from the university’s biological lab on Lake Erie to the campus in Columbus, where he became a lecturer in zoology and curator of vertebrates at the Ohio State Museum. He lectured in the classes of others but taught no course of his own. His doctorate was honorary, and there was the rub. Trautman had never gone beyond the eighth grade.

Born in Columbus in 1899, he suffered from abdominal pain and nausea that hindered him in school and at home left him peering from the curtains while others played outdoors. Not to suggest that a child’s torment is any sort of boon, but Edmund Wilson, in The Wound and the Bow, held that early affliction could foster a creative gift—a thesis for which Trautman might have served, with Dickens and Kipling, as a study. He did befriend a boy who had lost an eye to a toy arrow, the future writer James Thurber, the two of them sharing “the same type of ridiculous humor.” At a doctor’s urging, Trautman’s parents took him traveling; they went as far as Lake St. Clair, meaning to stop briefly before moving on, but when the boy wandered off to a pier and began catching perch, plunking them in a tub and raptly watching them swim around, the trip went no farther. For days he caught and contemplated tubs of fishes, releasing them at evening and making the first notes in a journal he would keep the rest of his life.

The ailment persisted, forcing him to quit school at age 14. When able, he explored the farm country around Columbus by horse and buggy, fishing the creeks and hunting rabbits and pheasants, observing all things wild, and fattening his journal. In time he went to work in his father’s plumbing business, becoming a master plumber, then took on a second job, seining streams to sample fishes for the state of Ohio. He would bend to haul a seine and throw up: so be it.

A week before his 30th birthday, surgery revealed and removed a Meckel’s diverticulum, a bulge in the small intestine. Healthy for the first time, he considered returning to school but concluded it was too late. As if to focus him on his métier, the doctor weighed in again. Two jobs, he advised, were too many. Trautman deliberated this and installed his last sink.

So he seined: day and night, all seasons, cooking meals on a plumber’s furnace, sleeping in barns. College was out of the question, but with the support and tutoring of scientists he knew in Columbus, he immersed himself in borrowed books and study afield. Hired, variously, by the state of Ohio, the University of Michigan, the Ohio State University, and others, he would manage always to work at the margin, on the fine line between institutional fealty and the freedom of the loner. In 1940 he would publish his major work in ornithology, The Birds of Buckeye Lake, Ohio, a marvel of long-term intensive study on a cluster of compact habitats. (“I love old-fashioned acumen in the field,” wrote Aldo Leopold, reviewing the book, “and I welcome Trautman’s proof of how good a job it can do.”) In 1957 came The Fishes of Ohio, rigorous in its science yet readable to nonscientists, concise despite its page count, as peerless in its way as Audubon’s Birds of America. He produced in addition a stream of papers, not all on Ohio subjects. In Yucatán he described new taxa of birds; in Alaska he studied grizzlies and salmon.

Eventually he would become a professor—though not yet in 1968, my senior year, when one day in May is indelible: spring in the air, protesters in the administration building, classes skipped in solidarity. Trautman is to lecture to the advanced ornithology class I’m taking. Trautman lecturing on birds is akin to Teddy Roosevelt busting trusts in your political science class. Everyone shows up.

Atop a long cabinet, he has set out study skins from the manifold families of American birds. The display is dazzling: waterfowl, pheasants, warblers, and more, among them a Kirtland’s warbler with a tag dated May 24, 1954. Not mentioning the cranial mode of its collection, he dwells instead on the subtle distinction between two ducks, the greater and lesser scaups, a question of the cast of the head’s iridescence, green versus purple, elusive to student eyes. He stresses the value of skins in research, and moreover the need of them, not sightings alone, for reliable records as humanity multiplies and habitats vanish. The talk begins in taxonomy, drops back to evolution, coalesces in ecology.

Someone ventures to ask about the “Original Vegetation of Ohio”—the heading of a chart on the wall, which depicts, in different colors, patches of prairie, beech-maple forest, and so on. “No no no,” protests Trautman, in high register, to the inquirer, much taken aback. There’s no such thing as the original vegetation of Ohio, we’re informed, unless we want to count spores in the late Silurian. The point is taken; the chart, exploded, seems to have no business being there, aside from baiting the unwary into a critical frame of mind. “Anything I can’t identify without a microscope,” he adds, speaking of spores, “I don’t care about.” Of course, he can’t mean it. On the way out, I say so.

The topic of microscopes, it’s true, is a trifle quirky. Lurking about it is the classic Thurber story “University Days,” relating the writer’s inability, in a botany class at Ohio State, to see anything in a microscope but his eye’s own reflection.

“I play to the gallery,” confides Trautman, dropping a bobolink back in its drawer.

A nippy evening in September 1982, the dusty-sweet haze of harvest in the air. Chimney swifts twitter above Big Darby Creek, a sycamore run looping through level farmland, a couple of long stone-skips wide.

Five of us file across a riffle, Trautman midway in the file, then clatter along a bank of cobbles pink with smartweed. At the next riffle up, we unfurl the seine, eight feet long by six feet high, quarter-inch mesh, a wooden pole and a graduate student at either end. The students wade upstream with the seine bagging a bit in the current, skimming the streambed. Trautman looks on, focused as a crow. “You’ve got it,” he affirms. “That’s how I used to get ’em.”

Used to takes in a lot of interval: since 1924 he has seined this spot at least yearly, usually several times a year. In that span Big Darby has stayed passably healthy for an Ohio stream, cutting a wide arc around Columbus and its effluents. On this particular stretch, known to researchers far and wide as Trautman’s Riffle, more fish species have been found than anywhere else in the state.

The students, Craig Ciola and Rich Carter, kick along a bed of water-willow and then lift the seine, spreading it on the cobbles for a look at the contents, a clump of yellow leaves and a scatter of fishes, finger length or less: a silver shiner, rainbow darter, and a momentary puzzler Trautman identifies as a sand shiner.

Everything goes wiggling back to the creek, though not before Ted Cavender, curator of fishes at the Ohio State Museum, logs the species and numbers. These data are not quite trivia, but for present purposes are a bit beside the point. Cavender has a federal grant to locate, against the odds, a living example of a long-lost species known only from Big Darby Creek, only from Trautman’s Riffle, and only from 18 bottled specimens.

Trautman leads off now, wading backward ahead of the seiners, his hands on their shoulders. “Too much mud there,” he tells them, changing course when a brownish cloud of silt boils up. “The best place is where the current is fast enough to wash away silt but not so fast it washes away sand. When you seine for the Scioto madtom, your feet aren’t supposed to sink.”

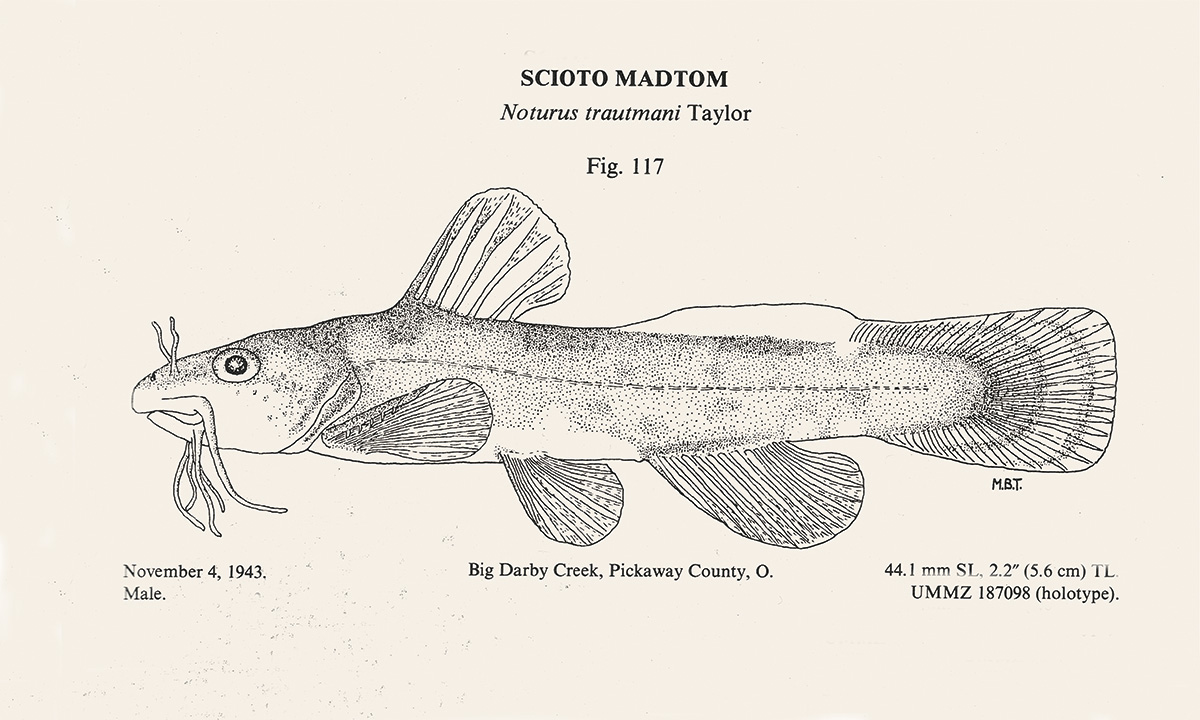

The Scioto madtom, Noturus trautmani, is, or was, a tiny catfish, two and a half inches at most, lumpy, olive-brown, with a palooka jaw and an array of dorsal and pectoral spines that can inflict a painful neurotoxic sting. Trautman seined the first two specimens in November 1943, at this same spot; a month later, the creek frozen except for the riffles, he caught another, wading with a seine while his wife, Mary, stood by in a snowbank with the collecting jars. One more was taken in 1945, and a phenomenal 14 during the fall of 1957. Since then, nothing.

And not for any lack of trying. In Ohio’s streams and its swath of Lake Erie, Trautman estimates he has caught or identified more than a million fishes. He has relied also on other seiners, notably the Riffle Rangers, a group of colleagues and students, and has examined every major collection of Ohio fishes, from the Smithsonian to the California Academy of Sciences. The written record factors in, too, back to Rafinesque’s Ichthyologia Ohiensis (1820). In all this effort, no single site has been sampled more consistently than Trautman’s Riffle on Big Darby Creek, where, clearly, that work continues.

The seine turns up a northern madtom, a species unknown here until Trautman collected one in 1957 but now grown numerous. “It may have crowded the Scioto out,” Cavender theorizes. Trautman thinks the northern may be more recent on the evolutionary scale, more adaptable to silt and pollutants. He palms the creature, standing it on its pectoral spines. It opens its froggy mouth and emits a faint croak.

“You don’t want to get stung by a big northern,” warns Cavender.

“I don’t want to get stung by any of them. The worst one is the mountain madtom.”

“Never got stung by that one.”

“Next time I get one, I’ll bring it to you.”

The sun dodges low in the trees and we all put on headlamps. With the fading light our chances may improve: madtoms forage after dark, coming out from seclusion under rocks and in the burrows of crayfish. The next lift yields a sodden wad of box elder leaves, amid them a stonecat madtom, ornate with orange fins, and a three-inch hellgrammite, an insect larva with a pair of stout pincers, which it sinks deep in Ciola’s finger, eliciting a wince.

“Beware the Jabberwock, my son!” whoops Trautman, not passing up so prime an opportunity to quote his favorite poem. “The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!”

Esprit, then, in spite of it all. No one here would deny the quixotic nature of the evening’s quest. A decade ago, Trautman lamented to me that half the species in The Fishes of Ohio had become so depleted in the state, he wouldn’t be able to find them again. That may have been a bit pessimistic: when advocating for the environment, he’s not one to sugarcoat. Gloom isn’t his mode, though, even in a book that describes loss so unsparingly.

It opens with a comprehensive natural history of the state, from its successive glaciations to the headlong revisions by humankind, in which Ohio comes to seem, in many ways, a microcosm of the continent. Species accounts make up most of the volume, with maps of collection sites and scientific drawings of every fish. Trautman did most of the artwork, taking precise measurements, with calipers, from a representative specimen and transferring these to the portrait. Dots representing individual chromatophores—pigmented cells—were inked in under a microscope, as many as 50,000 per drawing. In every aspect, The Fishes of Ohio became a model for studies elsewhere; when it sold out, used copies going for $200, the American Fisheries Society passed a resolution calling for a reprint. Trautman went to work on a larger, updated edition, 782 pages, issued in 1981.

In truth the book was an intertwining of effort, his and Mary’s. The two met in the summer of 1939, at the Stone Lab, Ohio State’s biological station on Gibraltar Island in Lake Erie, where Milton was doing ichthyological research and working on the book, and where Mary, with a PhD in entomology and a faculty post at Ashland College, had served as summer librarian. They married the next year and in 1943 had a daughter, Beth. Mary helped compile data and edit manuscripts for The Birds of Buckeye Lake and The Fishes of Ohio; the latter would take 15 years to finish, and without her support and contributions might never have wrapped up at all. In 1978, rightly, Ohio State awarded not one Trautman an honorary doctorate, but two.

Full dark now, temperature in the 40s. Cavender calls it a night. Twenty-nine species, but not the grail. We turn back downstream, Trautman not quite ready to quit. “I don’t think the Scioto madtom is extinct,” he muses, or merely insists. Indeed the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service will continue, as of 2021, to list the species as endangered. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature will beg to differ, having labeled it extinct in 2013.

Midway in the last riffle down, knee-deep, Trautman stops and makes a show of yanking his waders up to his chin. “You know,” he says, his nose highlighted under the headlamp like the comical beak of a character out of Dickens, “this really has been an unsuccessful night. Nobody’s been stung by a madtom.”

The scientific drawings for The Fishes of Ohio , often inked under a microscope, became a model for studies elsewhere. (From The Fishes of Ohio)

Dawn: a breeze stirs the cattails on Buckeye Lake. Kevin Ciola (Craig’s brother) and I set out the decoys, then row back to the blind, where Trautman waits in top sportive form.

“I’ve decided,” he declares judicially, “I’m not going to let you guys come in.”

We climb in. The blind is just big enough for the three of us, a frame of two-by-fours with sheaves of cattail tacked on for camouflage. It perches a half mile from shore, atop the remnant of an old towpath where a canal once ran through the lake. Trautman props his shotgun in a corner and takes up instead a 20X spotting scope mounted on a walnut gunstock worn smooth, he says, by a hundred years of handling. The decoys bob in the wavelets, a clump of 20 mallards to the left and a crescent of 40 scaup to the right, an opening between. We wait.

The birds of Buckeye Lake, Ohio: he began studying them formally in 1922, for the book of the same name. The project may sound parochial, but it renders a reality with broad ecological relevance, rooted in 12 years of intensive field study on 44 square miles of mixed habitats, including the seven-mile-long lake itself. All this he did on his own time and dollar, no grant beyond one for the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology to publish the 466-page book.

The sky pales; gaps open in the ring of cottage lights around the lake. The legal shooting time, 7:20, passes without a glimpse or whisper of duck.

From a blind on this same spot, Trautman has seen as many as 40,000 ducks migrating south in a single day. That was before 1930, when draining began on the northern prairie potholes where the ducks nested, and before Buckeye Lake was girdled with concrete walls and cottages and tarted up with an amusement park. He devotes a hundred pages to the human and natural history of the study area: Native Americans, early settlers, and market hunters (the last still living as he began his work), the cutting and burning, the draining and eroding of fertile topsoils. One gets a sense, from this saga, of the synchrony of settlement and desecration, and how Buckeye Lake nests seamlessly in the nation’s story as a whole.

Sunrise, 7:55, a slice of red-orange under an outcrop of clouds. Wisps of fog slither along the water. Then high overhead flits a mere speck, Trautman calling it a wigeon. To see as keenly, as intuitively, as he sees, a half century older than the two of us with him, a pipe fitter and a sleep-deprived writer: now a high flight passes over, and he’s the only one who can spot it with the naked eye. Scaup, he says, seven.

He holds out hope for an 11 o’clock flight, a phenomenon he first heard about from the market hunters. He surmises these late flyers are ducks from Lake Erie, a hundred miles north, taking to the air at dawn and heading southward. “The ridiculous part is, when the time change comes, we still look for them at 11 o’clock.”

The heart of The Birds of Buckeye Lake consists of its accounts of 282 species, much of it reading like narrative more than monograph, rich in anecdote, objective but with an occasional dash of metaphor and whimsy, Trautman the pal of Thurber not always able to suppress the inner wag. Flocks of ducks, with their daily comings and goings, are likened to the crowds and “attendant bustle” in a railroad station. A red-headed woodpecker, having busied itself for hours stashing grains of corn in the wrinkled bark of a tree, “helplessly fluttered about and watched the robbing of its granary” by a red squirrel. A largemouth bass lunges at—and misses—a low-flying kingbird. Prothonotary warblers build a nest in a bucket hanging in a boathouse, which, on windy days, they can enter only by timing the waves and flying in under the door. Red-backed sandpipers spot Trautman’s eye peering out from the rocks, then creep within two feet, twitter, and settle “in a most meditative fashion” to keep watch on the eye.

We sit like stone buddhas when out of the sun comes suddenly a single duck, whistling fast over the decoys, stealing a look, not set to alight. Trautman takes the crossing shot, having traded scope for shotgun by some sleight of hand, then rows out alone to retrieve the bird: a young drake mallard, green flecks on the head reflecting the sunlight. For the record he’ll note its stomach contents, but nothing more. “That’s a duck that’s not going to be made a skin. I’ve eaten so few ducks with skin on them.”

Indeed, most of his shooting has been collecting, without which museum cupboards would be bare, and ornithology, and biology in all its guises, would be a bit ethereal. The necessity of specimens: nobody likes to think his stent insertion depends on poking around in a cadaver, but nobody wants a surgeon who skipped that day in med school. And it is true that Trautman, no less than Audubon, is a hunter by instinct. Hunting, he wrote in a review of a book on the pursuit by the novelist Vance Bourjaily, “can be ignoble and degrading, or ennobling or elevating.” The hunter, mindfully, “hunts to find himself, and in his best moments succeeds. At such times he is looking down both ends of his shotgun.”

Or, as another pundit put it: “These modern ingenious sciences and arts do not affect me as those more venerable arts of hunting and fishing.” So wrote Thoreau.

A great blue heron lumbers past, a bill with a belly. Then a snow bunting, weeks ahead of schedule, flying fast. Having arisen at 3:45, we break out the lunch early, homemade dills and ground-up Canada goose in sandwiches made by Mary.

“Milton,” I commence, plugging a conversational gap, and rattle on about a field trip with a mutual friend, a famed nature cinematographer. The capper is, on returning to his car we found on its windshield a fresh, fat splatter. “Dammit,” wailed the friend, “that’s what I get, after all I’ve done for the birds.”

“Well,” offers Trautman, finishing his sandwich, an eye on the sky, “in the final analysis, what have we done for the birds?”

Silence, aside from the nattering of coots. The 11 o’clock flight never shows.

On a July morning when Milton was 84, we set out from Columbus and drove north, the two of us, through some of the flattest country in the state, and the starkest. Old fencerows ripped out, corn and soybeans clear to the horizon, relieved now and then by a forlorn woodlot—farmland like this, he pointed out in a paper long ago, was losing out to cities for diversity of birdlife, by default.

Sometimes the sepia rear view looks livelier. Together we’d fished creeks for smallmouth bass, slogged through marshes hunting for rails, and climbed a promontory where no glacier had ever gone. Best of all, though, he’d made the trip to Florida, where I lived, on the promise he extracted from me of a five-pound bass, a thing he’d never caught, and which might not have proven necessary, given the delight he took in our nearly two-year-old daughter, who swept a wildflower field guide up to her nose to sniff the pictures. Beyond all promise, he caught his bass: an epic specimen he carried back, on dry ice, to the Ohio State Museum.

On this summer day, heading north to Lake Erie, we cleared the cornfields and caught the ferry to South Bass Island, and from there a university launch to the cliff-edged little island of Gibraltar, where Trautman had worked on his book and taught for so many years, and where now he was to speak once more: the Last Naturalist’s last lecture. The room filled with students, the evening sun flickered off the water, the harmonies of boat motors played through the windows. From the lectern at the Stone Lab, he rehearsed what humankind had done to Lake Erie, most of it in his own lifetime, though he began further back with the plowing of lake plains that once had grown tall with grasses, their roots holding the soil and the soil holding the roots, the siltation that followed, the industrial waste and fertilizers, the loss of mayflies that once had slicked the lanes of lakeside villages, and the forfeiture, one by one, of species that sustained the commercial fishery.

Aside from basic remediation, he doesn’t presume to say what to do about it. In fact, there are too many people in the watershed, a situation unlikely to turn around. “Before the white man came, with his uncanny ability to exploit, destroy, and modify his natural environment …” It’s the sort of basal, almost biblical sentence that finishes itself.

For an hour we sit listening in squeaky wooden chairs, with scarcely a squeak. At the end, Trautman steps down to take questions. A student with her hair in an artful snarl wonders how it is that he has managed to do the disparate sorts of work that suited his leanings—and is it doable today? “There’s so much to know now,” he tells her, kindly. “No one can do what I did, thrash around in two different disciplines. The time for that is past.”

No doubt. But the two books endure, the 130 papers, the 15,000 pages of unpublished journals, and a third book, which he’s working on now, a bit fitfully, Birds of Western Lake Erie—and which his friend Ronald L. Stuckey will edit and publish in 2006, 15 years after his death.

In the course of the lecture the sun has bowed out. Stuckey, a professor of botany, sits with us now on the lawn, looking across the bay to the lights of South Bass, the masts of moored sailboats bristling like sedges in a marsh. On a dock piling nearby, a black-crowned night heron perches motionless, a funerary effect.

“When nature removes a great man”—this is Emerson, prophetic for our purposes—“people explore the horizon for a successor; but none comes, and none will. … In some other and quite different field, the next man will appear; not Jefferson, not Franklin, but now a great salesman; then a road-contractor; then a student of fishes …”

And of birds.

Rock music thuds from a saloon across the water. The Perry monument lights up, rising atop its reflection, the scene of Trautman’s anointing, after a day in his garden, by the Kirtland’s warbler. Not so different from his naturalist forerunner Thoreau, who, hoeing his own garden when a sparrow alighted on his shoulder, felt “more distinguished by that circumstance than I should have been by any epaulet I could have worn.”

Trautman bids goodnight and starts toward the island dormitory, a towered old hulk that seems to mirror, darkly, the monument across the bay. “I don’t know when I’ll get up,” he says, breaking out his mildest smile, “but I’ll get up. I always have.”