What a Fish Knows: The Inner Lives of Our Underwater Cousins by Jonathan Balcombe; Scientific American/Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 304 pp., $27

“Okay, so what can I eat, Mr. Balcombe?” was just one reaction I had to What a Fish Knows, which, among other things, demolishes the common justification for eating fish: namely, that they aren’t sentient and don’t feel pain. According to Jonathan Balcombe, they are and do. He cites a slew of field and laboratory studies that suggest that fish can innovate, cooperate, strategize, use tools, and pass on knowledge. As for pain, studies imply that they not only feel it but also recognize suffering and distress in others and sometimes respond helpfully.

Some of the studies he cites would be newsworthy if they related to higher mammals. In one, scientists put food into a plastic pipe to see whether stingrays could figure out how to extract it. They did, some by moving their fins to create a current through the pipe, others by using their bodies to create suction. Seeing this, the diabolical scientists added extensions to each end of the pipe, one of which contained wire mesh to prevent the food from coming out. All the rays quickly turned their attention to the end that was not blocked, and one invented a new way to move the food—by blowing water from its mouth through the pipe.

What a Fish Knows fits into a fast-expanding literature on intelligence and consciousness in creatures that scientists had all but ignored until recently. Researchers have more typically studied animal cognition in big-brained, long-lived, social species with protracted juvenile periods. But more and more studies have begun to document seemingly intelligent behavior in small-brained, short-lived, solitary animals. Octopuses live only five years, for example, but can go tentacle to toe with orangutans when it comes to plotting complicated escapes (as evidenced most recently by an octopus named Inky, whose escape from a New Zealand aquarium received worldwide attention). Lately we’ve seen a flood of books on the intelligence of birds (such as Jennifer Ackerman’s The Genius of Birds), and now Balcombe asks us to consider the possibility that fish are capable of feats of intelligence we once thought unique to apes, whales, and humans. What’s next, Machiavellian worms?

The late pioneer of animal cognition Donald Griffin argued that nature might endow all sorts of creatures with some degree of consciousness simply because it is more efficient than hardwiring every organism to respond to every conceivable challenge. As Balcombe puts it, referring to some of the sophisticated things scientists have observed fish do, “brain size be damned, if it’s critical to a species’ survival then that species will most likely be good at it.”

This attitude, radical though it may be, is simple common sense from an evolutionary perspective. The term “convergent evolution” describes how natural selection tends toward optimal—and similar—solutions to specific physical challenges even in species with vastly different genetic histories. Is it unreasonable to wonder whether this principle applies in the mental realm, too?

Indeed, another great gift of Balcombe’s book is to deepen his reader’s appreciation of the natural magic of evolution. Although water dominates the planet, we have difficulty grasping what it would be like to evolve and live in this fluid medium, where gravity really doesn’t matter, and where the depths offer an evolutionary stability unknown on land. In the oceans, nature has had a long, long time to work things out. Sharks first emerged 450 million years ago, 220 million years before the dinosaurs, and since then have survived five great extinction crises. (Whether they will make it through the present, man-made extinction crisis is anyone’s guess.)

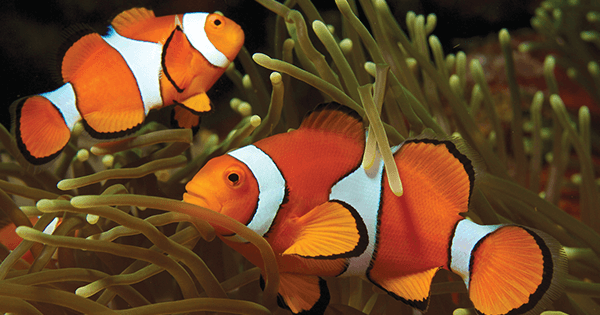

But nowhere is the full glory of natural magic more prominently on display than in reproduction. Hot tip to the North Carolina legislature: if you’re worried about LGBT bathrooms, you might want to skip this chapter. Romantic notions aside, sex in the aquatic world is about finding the best possible mate to perpetuate the species—and in the quest to do so, anything goes. Some fish change sex more than once, depending on which one might be more advantageous at various stages of their life cycle. With clownfish, when the breeding female dies, the top subordinate male switches to female and becomes the breeder. Male seahorses take yet another approach to blurring the gender divide: they fertilize eggs in pouches attached to their abdomens and then expel the hatchlings—“give birth”—once they’re viable. Meanwhile, other fish compete for mates in ways more familiar to humans: some guppies have penis-like appendages that account for 20 percent of their body weight, and the mosquitofish’s “penis” can extend to 70 percent of its body length.

Balcombe covers the waterfront, so to speak, from fish cognition and perception to their social structures and breeding practices, all the while drawing on a dizzying array of experiments and studies. In the hands of a lesser writer, the sheer weight of material could have overburdened the reader. But Balcombe’s prose is lively and clear, showcasing his gift for pithy sentences.

Will he succeed in changing the way we look at fish? So far, the public is much more open than the scientific establishment to accepting evidence of animal intelligence. That’s changing, though, as a greater number of field scientists simply begin to accept what they observe. Such progress, while welcome, does not readily translate into more enlightened and sustainable habits and diets. The scientific recognition that farm animals feel pain has not stopped the great bulk of humanity from eating meat; neither will such recognition stop the great bulk of humanity from eating fish. Still, a world populated by many minds seems far more interesting than the monotonous landscape inhabited by only one sentient species—the traditional view of Western science. What a Fish Knows goes a long way toward showing just how rich and varied that tapestry is for life forms inhabiting four-fifths of the biosphere.