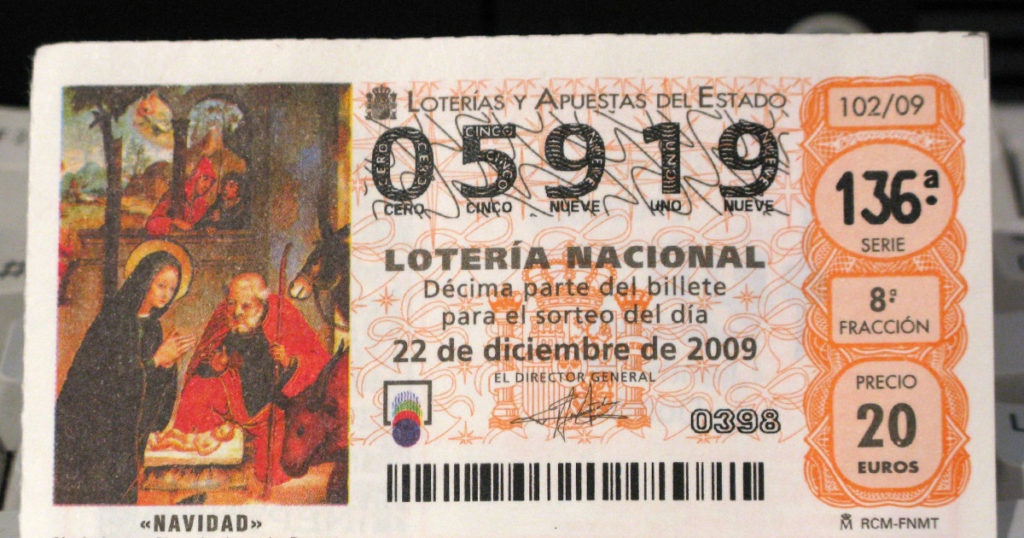

Me tocó is the happy cry of anyone winning the state Christmas lottery, on December 22, or the Kings’ Day lottery on January 6. El gordo is the big cash prize, but smaller amounts are awarded too. A ticket is a common gift among friends or family and is often a prize at competitions, and selling portions of tickets is a way for kids to pay for school trips or for clubs to add to their coffers. So instead of the individual me, it’s often the plural, nos.

Nos tocó, which literally means it touched us, is used for bad luck as well as good, and in English I’d have to say “What are you going to do? It’s just how things turned out,” to approximate a Spaniard who says, “¿Que se va a hacer? Es lo que nos tocó.” It’s a common Spanish sentiment, often said with a shrug or a quick shake of the head to emphasize that bad luck just happens, it’s dealt out blindly, no right or wrong about it, no sense in protesting it. In addition, nos tocó, which also means it was our turn, suggests that though random, everyone is in for some of it. That’s how it was said by the workman who was in my classroom a week before Christmas to seal the windows. He’d made a joke about getting his high school diploma at 42, after a question from his son had piqued his interest in a subject he knew nothing about. A couple of years of night school, and he was finished.

The man was part of a crew that had been working on the building façade for some eight months, and now they were almost done. The scaffolding had been taken down, the work sheds hauled away, only a last touch on the windows remained. He was shorter than I am, very slim, swarthy with a scruffy beard, an earring, and a modified mohawk. He looked like a pirate.

But no, not a buccaneer but a family man, inspired by his son. That’s a happy story, I thought. The workman and his workmate had finished with the windows, and I considered what to say next to wrap it up. I wondered if there’d been some friendly competition between father and son, comparing grades. “How old was your son then?” I asked.

“Let’s see,” he said, then counted back the years. The diploma took him two years to finish, he was 42 when he got it, 48 now, his son was 15 now, so he would have been 7 at the time. “Ah,” I said, “so you graduated before your son.”

Right, he said, and now his son was working on the ESO, the preliminary degree. Then he added, “He has cancer, so he gets classes at home. Of course, they don’t expect the same work from him.”

I was shocked. “Oh,” I said, “I’m sorry.”

“We have an appointment tomorrow. We’ll see what the doctors say.” He was moving toward the door.

“That must be so hard.”

An awful year, he said, then shrugged and raised his eyebrows. “Es lo que nos tocó.”

It’s how things turned out, it’s our lot, it’s what we have to live with. Any of that, all of that, was in his expression, but no self-pity, no fear, and nothing like lethargy or defeat. A shadow of confusion flitted across his face, as if from the awareness that he was in a game with rules he hadn’t set and didn’t care for. Otherwise, just the shrug.

That day’s brave face didn’t mean he’d have the same face after talking to the doctor, or on taking his wife’s hand in his, or when opening the door to let in his son’s teachers. He’d have a lot of faces, and the one I saw was just the one he put on that day, a week before Christmas, a day before yet another report from the doctors, at the end of a hard year. Nos tocó, he’d said, but it wasn’t likely he’d be saying it about either of the holiday lotteries. He wouldn’t win those, and he wouldn’t care. His heart was set on a different win.