The Lotus Position

What does one of television’s biggest hits have to say about the nature of a certain kind of American tourism?

At the beginning of 2022, I decided to travel the world and be a nomadic writer. I didn’t want an itinerary; I just wanted to be free. But the problem with that plan arose right away: I didn’t know where to start. A few years before, on a visit to Florence, I had fallen so deeply in love with that city that I almost stayed for four months to study painting. (I don’t paint.) I briefly contemplated a return to Florence before discovering that rental rates there had skyrocketed. Because of the pandemic, prices for all sorts of things had spiked around the world, but still, the cost of living in Florence seemed particularly high. Instead, I decided to start my journey in Málaga, in the Andalusian south of Spain.

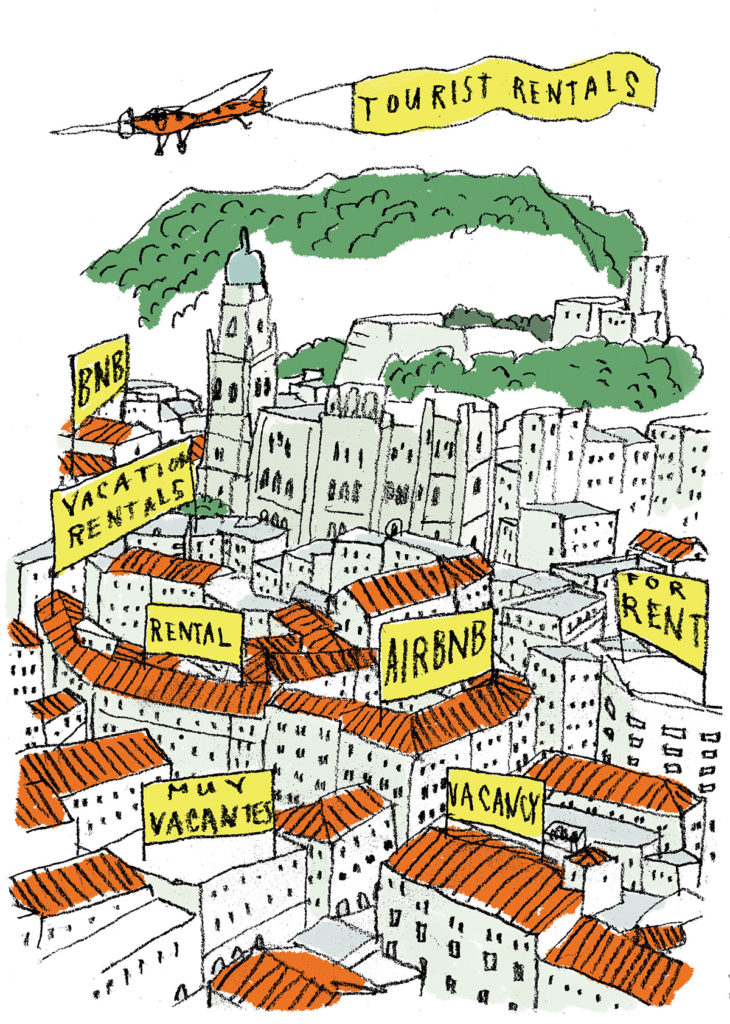

It was the low season when I was there. Nevertheless, tourists escaping the northern cold continued to come in droves, taking advantage of what they perceived to be a low-cost vacation—and transforming the city before my eyes. Residents complained of being pushed out of the city center to make way for more Airbnbs, like the one where I stayed for three months. (In my experience, the longer the rental agreement, the lower the cost. A contract for anything less than a year cost significantly more than what Malagueños would pay but was still drastically cheaper than the going rate in most American cities.) Some residents who owned large apartments were moving entire families into a single small bedroom so that they could rent out the remaining two or three bedrooms to tourists. One day, a café was advertising a main course, dessert, and drinks for eight euros; the next day, the same meal was going for 18 euros. Gone were the café’s comfy couches, replaced by a long bar where tourists could plug in their laptops, with a maze of extension cords that couldn’t possibly have been legal. I knew that I was at least partly complicit in all of this, that the presence of tourists—particularly Americans and Northern Europeans—was changing the economy to such a degree that the local population was being priced out of housing and becoming displaced. In a couple of years, I realized, Málaga could turn into Florence.

It was at this time, and with these thoughts present in my mind, that I began watching season two of the HBO hit The White Lotus. The series, which has won a host of Emmy and Golden Globe awards and was picked up for a third season, takes place at outposts of a fictional resort chain (the White Lotus). The first season is set in Hawaii, the second in Sicily, and the show’s creator, Mike White, has hinted that the third may be located somewhere in Asia. These locations are opulent places where the rich can luxuriate and behave badly, and they are meant to inspire the rest of us to daydream—even as we witness the various psychosocial dysfunctions that affect both employees and guests.

The brilliance of the show lies in both the nuanced writing and the acting. It critiques wealth, power dynamics, and whiteness, and it attempts to depict how tourism can transform the physical landscape and economy of a place, as well as the very fabric of its culture. Relationships are redefined—not only those between locals and tourists but also those between locals and locals. And yet, this critical, satirical take on the luxury class doesn’t go far enough in addressing the devastating effect of American tourism on places like Sicily. Moreover, in a parallel thought about complicity, I kept wondering whether the writers were aware that they were perpetuating the same views that both seasons of the show were meant to satirize.

Amid the breathless coverage of the show’s first season, one character had remained overlooked and underexplored: Belinda, the resort spa manager, played by Natasha Rothwell. That Rothwell was nominated for an Emmy at once complicates and underscores the strange position shared by both actor and character, as Black women in largely white spaces. As a Black woman, I often get the feeling, in shows with a nearly all-white cast, that certain figures have been inserted simply to meet a diversity requirement. Belinda’s role felt like that to me. And I couldn’t help thinking of her during a trip I took to Marbella, a small resort city in the province of Málaga that’s known as a playground for the rich. During the summer, its population nearly triples, and because the climate is Mediterranean, the season extends well into October. You could easily imagine a White Lotus resort opening up there. At one very nice restaurant, I noticed that the only other Black person present was a woman who limped as she mopped the floor, making her way between the tables filled with luxurious food and extravagant wines. She attended to the bathrooms, which were spotless and fresh, yet because the patrons ignored her, it was as if she were not even there. Her tip bowl contained only a smattering of coins.

One thing that had been very different from my day-to-day experience in the States: in Spain, I had begun to feel unaware of myself as a Black woman in a largely white place. Spain may suffer from its own problems with racism, but for a while, I was oblivious of my situation, and I owned this obliviousness, happy not to think about it as I explored my new surroundings. But watching that woman work among the pampered restaurant diners in Marbella snapped me out of that phase. I thought not only of Belinda but also of the disembodied presence of Black women in literature and cinema—both present and absent in white spaces. In Playing in the Dark, Toni Morrison offered a critique of this phenomenon. “Through significant and underscored omissions, startling contradictions, heavily nuanced conflicts,” she wrote, “through the way writers peopled their work with the signs and bodies of this [Black] presence—one can see that a real or fabricated Africanist presence was crucial to their sense of Americanness.”

Belinda’s involvement in the plots of both seasons also has something profound to say about the effect of tourism on local residents. In season one, Tanya McQuoid—a character, played brilliantly by Jennifer Coolidge, who appears in both seasons—dashes Belinda’s dreams of owning her own business. In season two, Tanya sips on a drink and casually mentions Belinda, as if she’s an irrelevant, minor figure—no matter the emotional damage wrought when their relationship went to ruin. That Belinda actually comes off as more than simply a token presence is a credit more to Rothwell’s acting than to the character as written.

The main conflict of season one is centered on the effects of colonialism—in the form of modern-day capitalism—on a marginalized, indigenous Hawaiian population. Among the wealthy guests at the White Lotus are the Mossbachers, who have brought along their daughter Olivia (Sydney Sweeney), their son Quinn (Fred Hechinger), and Olivia’s friend Paula (Brittany O’Grady). In stark contrast to the Mossbachers is Kai (Kekoa Kekumano), a Native Hawaiian in desperate need of money who performs indigenous dances for the pampered guests. He also happens to be Paula’s vacation fling. Paula, a biracial Black girl, is so disgusted by the rich white people at the resort that she persuades Kai to rob the Mossbachers.

The plan goes awry, with the audience unsure if Mrs. Mossbacher is seriously injured or even killed—we still don’t know by this point in the show who is in the coffin shown at the beginning of the season. At any rate, Kai is carted off to jail, leaving Paula sickened by what has happened. But in the end, she goes back to her life and her friendship with Olivia, whom, for good reasons, she doesn’t like or trust. Quinn, meanwhile, who begins the season as your typical teenager glued to his phone, experiences tremendous growth, falling in love with the ocean life and running away from his family to live with the members of a local rowing team. As for Kai, he remains very much a stereotype, a symbol, not nearly as fleshed out as the white characters around him—a charge leveled by critics such as Mitchell Kuga, writing in Vox in August 2021.

“I didn’t know that I had the gumption to wade into those [colonialism] waters again,” Mike White said about season two in an August 2022 article in Vulture, “knowing I was going to get sniper fire from every direction. … Maybe the classic sexual politics, the naughty subversive stuff we’re getting into, will take the edge off a little bit from that.” And yes, sexuality, sexual politics, and sexual relations come to the fore in season two. If the vacationing guests inhabit the White Lotus bubble largely ignorant of the world beyond it, the Sicilian characters seem more in control of their lives than did the Hawaiian characters. These include sex worker Lucia (Simona Tabasco); Mia (Beatrice Grannò), Lucia’s friend and an aspiring singer who also dabbles in sex work; and Valentina (Sabrina Impacciatore), the resort manager. These women see the decadent wealth around them and are all too happy to take their cut.

In one storyline, Lucia manipulates Albie (Adam DiMarco), a recent college grad, out of 50,000 euros by convincing him that a local thug is threatening her. Nice guy Albie is a California progressive and so naïve that he spends the night with Lucia without realizing he is expected to pay for her services in the morning. But when he does realize, his response is so enlightened. He apologizes for not knowing, then promises to get her the money, which he does. Lucia initially falls for his innocence and considers a real relationship with this sweet and wealthy young man. But ultimately, reality sets in—she lives in Sicily, after all—and she uses Albie’s innocence to bag the 50,000 euros from him, a minuscule amount for his family.

I was both annoyed and fascinated to think that White thought that if he focused the season’s conflict on gender roles between lovers and friends—particularly the women, and more specifically Daphne (Meghann Fahy) and Harper (Aubrey Plaza)—that the arguments around colonialism would somehow become less fraught. And though the plots involving the Sicilian characters are brilliantly developed, it’s telling that in The White Lotus’s fictional worlds, the best hope for the future of humanity comes to rest on two young, white American men (Quinn in season one, Albie in season two). Do the writers and producers worry about what their narratives say with regard to their role in perpetuating the notion of white male superiority both here and abroad?

We anthropologists are acutely aware that when we arrive at a location to study its culture—when we attempt to unravel and unpack the things we observe—our very presence changes what we see. But the producers of The White Lotus are not anthropologists, and this otherwise dazzling show suffers from that fact.