Hidden Portraits: Six Women Who Shaped Picasso’s Life by Sue Roe; W. W. Norton, 304 pp., $35

Over seven decades, Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno Crispín Crispiano María Remedios de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz Picasso annexed women nonstop. To Marina Picasso, her celebrated grandfather was an obligate carnivore, in life and in art. “He needed blood to sign each of his paintings,” she declared in 2001—the “blood of all those who loved him,” adding later that he “submitted them to his animal sexuality, tamed them, bewitched them, ingested them, then crushed them onto his canvas.”

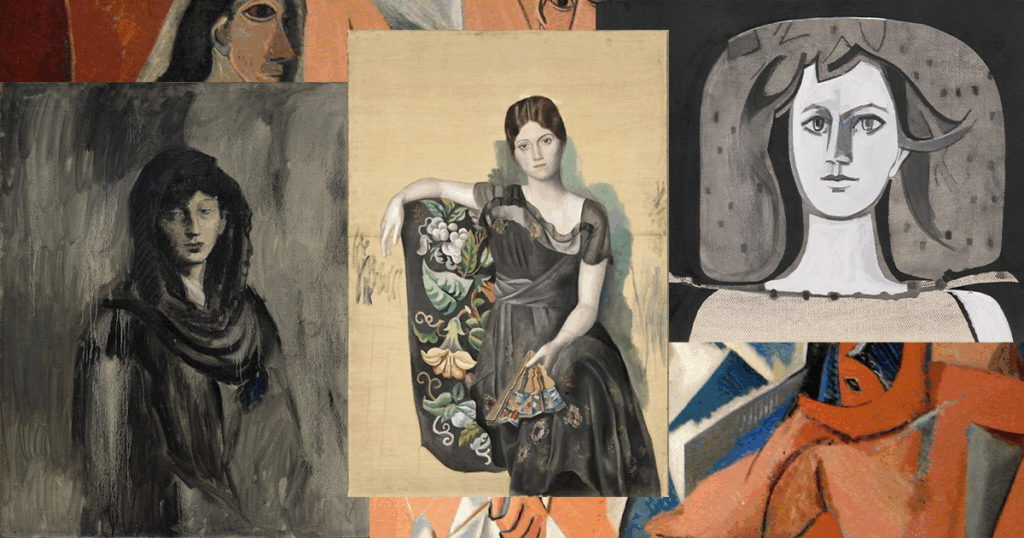

To generations of art experts, mostly male, a turbulent home life was merely a sideshow to Picasso’s phenomenal productivity, which resulted in the paintings that built modernism, from 1907’s Cubist marvel Les Demoiselles d’Avignon to the great antiwar Guernica of 1937. Two wives, four cohabitations: What of it? Genius has license to trample. Such has been Picasso’s excuse, but more recent historians, mostly female, side firmly with Marina.

What did Picasso’s women have to say on passion and fame? Two left memoirs, others gave interviews, but their eyewitness testimony has been sadly neglected. No more, thanks to Sue Roe, a British expert on Virginia Woolf also known for backstage art histories from both sides of the Channel (In Montparnasse, In Montmartre, The Private Lives of the Impressionists, Gwen John). Picasso, she realized, is the most thoroughly documented artist of the 20th century, but Fernande, Olga, Marie-Thérèse, Dora, Françoise, and Jacqueline were “invariably removed from centre-stage … dismissed as his supporters, companions and muses.”

Roe returns all six to the spotlight, and her glimpses of life chez Picasso charm and chill. He could be marvelous company when in the mood, washing dishes, dandling babies, bestowing perfect presents. But always there is the lover stashed in the garden shed, always that trail of blood. Hidden Portraits is the first book in English to inquire, at length, what kind of woman volunteers to move in with the Minotaur.

In Roe’s reframing, these six savvy moderns willingly sat for the artist, admired his work, and shared studios, apartments, houses, and holidays. They all ignored the advice given by Picasso’s mother to his first wife, Olga Khokhlova: “I don’t believe any woman would be happy with my son. He’s available for himself but no one else.” And all of them tried to keep some independence, when they should have been looking for a lawyer. For every 10 years or so, Picasso tore up one life and launched another. To recover this counterhistory was more than a challenge, given the coiled and overlapping amatory timeline, not to mention all the screaming.

“One problem—for him as for the women who loved him—was that Picasso was the marrying kind,” Roe writes. “He could never bear to lose anyone entirely.” Because he hated scenes, the constellation of the discarded kept growing, like the fata morgana of vast inheritance, as did the age gaps: His last wife was 26 to his 72.

Postmodern biography offers ingenious ways to configure female group histories, from The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper to the artist-colleagues of The Equivalents or Juliet Barker’s wise The Brontës. Roe updates the collective-lives tradition of Plutarch and Lytton Strachey, and her views on the biographer’s duty are firm: “We are not art historians, critics, journalists or novelists (though sometimes it feels as if we need to be all of them). We can only build a story from the facts available … put together, or retrieve, the hidden picture, with empathy rather than omniscience, to illuminate rather than judge.”

Roe’s safe, gray prose sometimes switches to panting purple: “We can only imagine the chemistry between the charismatic, seductive, black-eyed painter, who by all accounts exuded charisma even when standing still; and the poised, serious dancer.” Always and ever, biographical structure is crucial, chronology fighting it out with theme—and in Hidden Portraits, both take a beating. Biographies that run on romance can be tricky to elevate, ranging as they do from love triangles to polyfidelitous polycules; here, Picasso’s six amours are spokes to his hub, but the book never finds full balance because only three are genuinely interesting: the Parisian artists Dora Maar and Françoise Gilot plus much-maligned Jacqueline Roque, the pottery shop saleswoman obliged to deal with Picasso’s legacy. And so the narrative leaps and lags.

But Roe gives each one her chance, thanks in part to overlooked sources: photographs, memoirs, diaries, long-lost trunks of memorabilia. Fernande, the beguiling, scatty model who powered Picasso’s Rose Period, lived with him in bohemian squalor (though they could definitely afford opium). Picasso met Olga Khokhlova, a Russian dancer, when designing sets for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Next he picked up a blond sports-mad teen, Marie-Thérèse Walter, outside a Paris department store. (A man in a superb tie, she remembered, suddenly offered to paint her portrait. “I am Picasso!” he declared; she’d never heard of him.) The surrealist Dora Maar caught his eye with performance art at Les Deux Magots, one of the cafés favored by Parisian intellectuals. She wore black gloves embroidered with red roses, produced a knife, and slowly stabbed between each finger; Picasso was enchanted. Peak confusion arrives in 1935–37, when Marie-Thérèse bore him a daughter while Picasso was still married to Olga but also seeing the strongly anti-Fascist Dora, who photographed every stage of Guernica’s creation.

Only the poised Françoise Gilot walked out. They met in a café in occupied Paris. Picasso gave her a bowl of black-market cherries. She told him she was an artist. “That is the funniest thing I’ve ever heard,” he said. “Girls who look like you could never be painters.” Leaving was not liberating, she later explained, for she was never his prisoner, and as proof, she wrote the tart bestseller Life With Picasso, then married Jonas Salk, saying, “Lions mate with lions.” Two of her paintings sold for $1.3 million apiece, in Hong Kong and in London, before her death in New York at 101.

“The Woman Who Says No,” Picasso called her, and without Gilot’s bracing example, Hidden Portraits would chronicle mostly cruelty and sadness. The ardent bully who called women machines for suffering, goddesses or doormats, is 50 years gone. But Roe’s steady gaze helps us assess anew his monstrous, needy ways.