Eisenhower in War and Peace, By Jean Edward Smith, Random House, 950 pp., $40

Why has Dwight D. Eisenhower received such short shrift in the world of presidential biography? One reason is that Eisenhower was the only Republican president in an era of liberal dominance, his two terms bookended by four crucial Democratic presidents—Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry Truman before him, John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson after him. They and their string of liberal achievements—civil rights, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid—have enjoyed more attention than Ike has had, from admirers and critics alike.

Meanwhile, the contemporary conservative movement has turned its back on Eisenhower. Republican presidential candidates applaud Ronald Reagan as their hero, forgetting that Ike, too, was once a member of the GOP pantheon. His pragmatic streak runs counter to the conservative movement’s animating conviction that the federal government is an albatross around the nation’s neck—a sentiment that has fired up virtually every major Republican presidential candidate since 1980, leaving no room for tributes to a moderate president like Ike.

Numerous presidential biographies in recent decades have defended their subject’s greatness. Historians have reaffirmed George Washington’s brilliance, bolstered John Adams’s reputation, and resurrected Truman’s legacy. Now comes Jean Edward Smith’s Eisenhower in War and Peace, which seeks to lift Ike’s reputation just as David McCullough’s best-selling biography did for Truman.

Smith rates Eisenhower with FDR as America’s “most successful” 20th-century presidents, resting his assertion on the theory that Eisenhower orchestrated an era of prolonged peace, promoted international stability, and established a record of economic prosperity here at home. Eisenhower “ended a three-year, no-win war in Korea with honor and dignity,” Smith coos, “weaned the Republican Party from its isolationist past, … tamed inflation, slashed defense spending, balanced the federal budget, and worked easily with a Democratic Congress,” among other achievements.

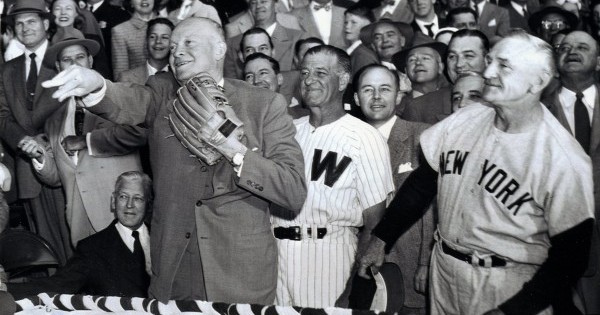

But Smith’s vividly written biography is more convincing in its portrait of Ike’s military career than in its lofty claim of his greatness in the White House. He shows that Ike’s penchant for order, his search for consensus, and his affinity for alliance building are all traceable to his military career. Raised in poverty in Abilene, Kansas, Eisenhower excelled on a competitive entrance exam, which won him a spot in West Point’s class of 1915. The academy provided him a gateway to a better life, and his ardor for football and other sports made him, one soldier recalled, a “physical culture fiend.”

Several hardships informed his early career. His three-year-old son died from scarlet fever in 1921—“the greatest … disaster in my life,” Eisenhower said—and work became a balm. But despite his eagerness to prove himself under fire, he missed participating in World War I by a matter of weeks. Learning of the Armistice, he vowed he would “[cut] myself a swath that will make up for this.”

Ike’s prediction came true. He commanded a newly formed tank corps based in Gettysburg, protected soldiers from the Spanish flu, and later helped the Army return to a peacetime footing. Superiors consistently lauded him as a natural leader who had a talent for organizing men and materiel and solving logistical challenges with speed and common sense. His assignments took him around the world—experience that proved invaluable in World War II and beyond, when he built a reputation as a skilled military commander with a diplomatic touch.

Eisenhower’s superiors pushed him up the ranks. Serving in the late 1920s under General John Pershing both in Washington and in Paris, Eisenhower helped write a comprehensive military analysis of the U.S. role in World War I. His assistance during the 1932 crackdown on the Bonus Army march in Washington blotted his record, but he went on to serve as General Douglas MacArthur’s virtual chief of staff in Manila, where MacArthur praised him as “a brilliant officer.”

Smith hails Eisenhower’s achievements as Supreme Allied Commander during World War II, when he held the fractious Allies’ coalition intact—winning the confidence of George Marshall, FDR, Charles de Gaulle, Winston Churchill, and even Joseph Stalin. Although his combat inexperience hampered his strategic decisions, he was adroit at building alliances and ultimately proved himself more political sophisticate than military genius.

Eisenhower in War and Peace leans heavily on details of military strategies and clashing wartime personalities—describing Patton’s antics and British-U.S. tensions, for instance. It devotes less attention to the evolution of Eisenhower’s politics and foreign and domestic policy views. In a book hailing Eisenhower’s presidential greatness, his presidency receives only 250 of its more than 750 pages of text.

Smith makes it hard to discern the origins of Ike’s progressive Republican politics. The book doesn’t fully explain why a commander in chief immersed in military culture learned to disdain McCarthyism and became such a strong defender of civil liberties. What effect did his son’s death have on his subsequent career and worldview? How did Eisenhower’s visit to the Nazi concentration camp at Buchenwald affect his understanding of human nature and war, and shape his approach to global affairs during his White House years? The book is silent on all of these questions. There is ample discussion of Ike’s mistress, Kay Summersby, but Smith shortchanges more consequential matters, like the origins of Eisenhower’s views on racial equality, his thinking on gender in 1950s America, his attitudes toward unions and corporations, and his economic vision beyond balancing budgets.

Smith argues that Eisenhower’s presidency was significant domestically because he accepted the New Deal as a legitimate social force and refused to heed the calls of bumptious conservatives to destroy the welfare state. Instead, Eisenhower practiced the politics of common sense. He agreed to expand the Social Security program, achieved racial integration in the U.S. military (building on Truman’s agenda), and repudiated the witch-hunt for Communists in the federal government and other domestic institutions. In doing so, Ike breathed life into moderate Republican politics as few leaders have done in recent decades.

But other aspects of Ike’s greatness in domestic affairs aren’t as convincing. His civil rights record was less robust than this biography claims: far from exercising moral leadership, Eisenhower’s politics were, above all, cautious, his approach, incremental. He framed his 1957 decision to enforce school integration in Little Rock as a simple defense of law and order—not an endorsement of racial equality.

Ike’s legacy as commander in chief is also a mixed bag. He refused to use nuclear weapons when his military and other advisers proposed it as an option to save French forces at Dien Bien Phu in Vietnam, brought a swift end to the Korean War, and expressed his antimilitarist convictions in a farewell speech warning of the perils of the military-industrial complex. But he nevertheless embraced anticommunism as the overriding goal of the nation’s foreign policy, ousted democratic leaders in Guatemala and Iran (as Smith makes clear), and led civilian defense drills across the United States that sent an absurd message to the public: nuclear war was actually winnable. His administration also helped usher in the age of the hydrogen bomb and the doctrine of “massive retaliation.”

Ike was exceedingly popular for much of the 1950s, but winning reelection doesn’t necessarily translate into presidential greatness. His campaign slogan, “I Like Ike,” evoked Eisenhower’s convivial personality but didn’t convey any policy ambition. Indeed, it left the impression that he felt more at home playing country club golf courses with his wealthy friends than using the bully pulpit to propound his vision of a just society. Though Eisenhower overwhelmingly won two presidential elections, Kennedy’s narrow 1960 victory was due, in part, to his critique of Ike’s incremental politics.

Smith’s defense of Eisenhower’s presidency is as engaging as it is ambitious and impressive. But the resulting portrait of Eisenhower reads too much like an effort to burnish his legacy. Ike’s presidency was more consequential and more fascinating than the literature on the ’50s conveys. A better-balanced treatment of Eisenhower’s White House years would have made this biography as subtle as it is smart.