The Mule on the Stairs

Remembering the school in the midcentury South where “We Shall Overcome” was born

It seems an unlikely place to have played such a vital role in a movement that shook America to its roots and changed the nation for the good. What remains of the place is unimpressive—just a couple of low-slung buildings on a bluff under pin oaks off Highway 41 between Monteagle and Tracy City, Tennessee, on the Cumberland Plateau. A historical marker gives a few details. Even its name is a bit of a puzzle.

The Highlander Folk School, in case you’ve never heard of it, was a progressive training school founded in 1932 where activists went to learn about nonviolent resistance in the early days of the civil rights movement. My partner, Suzy Papanikolas, and I met at Highlander when we were both 19. That was in 1960. She was a student at the University of Texas; I went to Sewanee.

The Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. was often at Highlander. He was friends with Myles Horton, the school’s founder and the inspiration behind its philosophy. A sharecropper’s son from Savannah, Tennessee, on the Tennessee River near Shiloh, Myles had gone to Denmark in the ’30s to learn about its adult education folk schools. There, according to Diane McWhorter’s book Carry Me Home: Birmingham, Alabama, the Climactic Battle of the Civil Rights Revolution, the approach was to encourage “an oppressed people [to] collectively hold strategies for liberation that are lost to its individuals.”

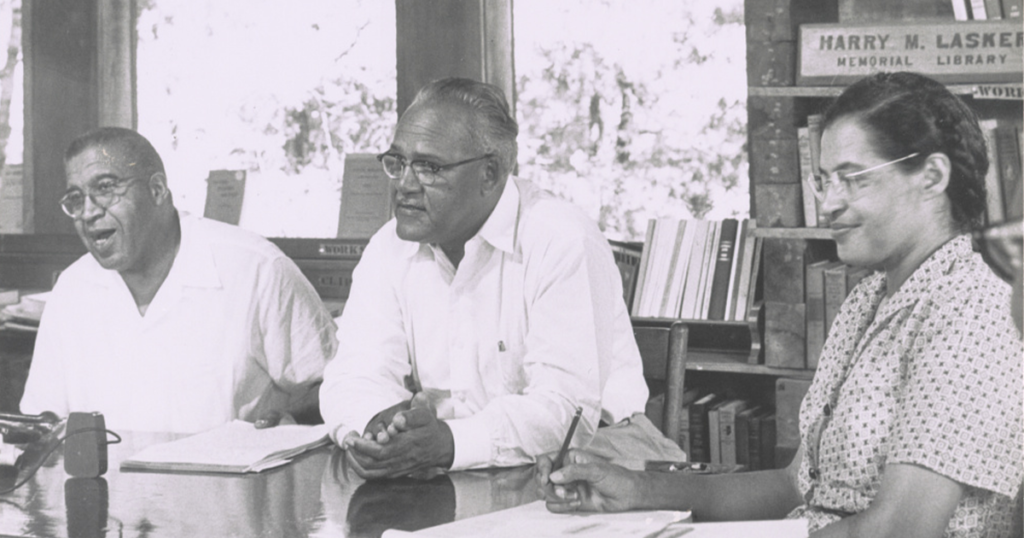

Dr. King would sometimes be accompanied by movement colleagues like the Reverend Ralph Abernathy; Congressman John Lewis from Georgia, another sharecropper’s son; the Reverend C. T. Vivian, who was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Obama in 2013; and Septima Clark, the African-American educator from Charleston widely known as the Queen Mother of the civil rights movement. People think of Miss Rosa Parks as a quiet little lady who got fed up with riding in the back of the bus in Montgomery, Alabama, and refused to give up her seat to a white man. Few know that before initiating the Montgomery bus boycott she studied nonviolent resistance at Highlander or that the boycott was part of a well-thought-out tactical plan. These days, as I drive up the freeway in Portland, Oregon, where my children and grandchildren live, and pass the exit for Rosa Parks Way, I wonder how many people in the cars around me know anything about her at all.

As for Suzy and me, I was from Memphis, she was from Southern California. Her sister, Nelly Bly, who was enrolled at Pomona College, had spent a year as an exchange student at Fisk College (now Fisk University) in Nashville. It was she who told Suzy about Highlander. Nelly Bly’s Pomona roommate Candie Anderson later married the folk singer Guy Carawan, who became Highlander’s musical director. Guy looked like a pirate in a black-and-white Hollywood movie. Working with Pete Seeger and Zilphia Horton (Myles’s wife), Guy adapted the Black spiritual and labor union song that became “We Shall Overcome.” Guy, Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, and their folkie friends had rewritten the words to traditional folk songs for the labor union movement in the ’30 and ’40s, and now they found they could do the same with spirituals. In an interview, C. T. Vivian remembers:

Here he was with this guitar and tall thin frame, leaning forward and patting that foot. I remember James Bevel and I looked across at each other and smiled. Guy had taken this song, “Follow the Drinking Gourd”—I didn’t know the song, but he gave some background on it and boom—that began to make sense. And, little by little, spiritual after spiritual began to appear with new words and changes: “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize, Hold On,” or “I’m Going to Sit at the Welcome Table.” Once we had seen it done, we could begin to do it.

Suzy and a group of other students from her race relations group at the University of Texas drove up to Highlander from Austin in the spring of 1960. To reach Tennessee, they had to cross Arkansas. They had heard it was against Arkansas law for Black males and white females to ride together in the same car, so they carried musical instruments—in case they got pulled over, they could say they played in a band. For me, the trip to Highlander was shorter and less arduous. I was a student at the all-male, imposingly named University of the South, just a few miles up the road from Monteagle in Sewanee. Friends of mine and I would go down to Highlander to listen to lectures and sit in on seminars.

An old upright piano stood against the wall in the main meeting room, and there were always guitars and autoharps and fiddles around. Or if no music was going on, we would hang out and drink beer from the icebox, putting a couple of bucks in the “honor box.” From time to time we’d get to sample the sprightly moonshine and applejack that Myles, who enjoyed a drink as much as the next man, acquired from his friends in the coves and hollers. I could play a few chords on the guitar and knew some songs I had learned off records by Woody Guthrie, Joan Baez, and the Weavers. And Suzy could sing too—after all, she played in a band, remember?

Having grown up in Memphis in Jim Crow days, I didn’t know too many people from backgrounds other than my own. I hadn’t left Tennessee yet, and here were all these people from exotic places like California and New York City, along with African Americans who looked like people I had been around all my life but had never really gotten to know. And in the few cases I had gotten to know them, it was always on terms dictated by the system of apartheid that governed our every interaction.

As students at our separate universities, Suzy and I got involved in sit-ins and other efforts to try to bring about change. My hometown and the adjacent Mississippi Delta were, as everybody knows, one of the most virulently racist regions in the world. But among the many goodhearted people in East Tennessee, there was also an Appalachian racism, and many in Franklin, Grundy, and Coffee counties hated what we were trying to do.

Compared with the harassment, intimidation, and physical beatings endured by civil rights heroes like those I have mentioned, and the police dogs, tear gas, water cannons, church burnings, shootings, and bombings they were subjected to and endured, what we did at Sewanee was a cakewalk. Sewanee was a different place, an Episcopal Church school, an island of civility on the Cumberland Plateau. Nobody threatened us, spat on us, dumped food on us at lunch counters, beat us up, shot or turned water cannons on us, or bombed our churches. I never even caught a whiff of tear gas until a decade later, during the demonstrations and street battles in Berkeley. The worst I suffered at my college was social ostracism in some quarters and the occasional sotto voce “N-word lover!” muttered in my presence by a fellow student.

In times of societal stress, when a culture’s core values are challenged, as they were during the fight for desegregation, fault lines develop and the ugliest of human emotions rise to the surface. One of my classmates, a mild-mannered French major whom I’ll call Perry, invited an African-American girl he met at Highlander to a fraternity dance at Sewanee. I don’t think Perry was trying to prove anything; he just liked the young lady. A couple of nights after the dance, a group of students kidnapped Perry from his room, took him up to the roof of their dormitory, shaved his head, and painted it black. This was disturbing for all kinds of reasons. I remember thinking you might expect that kind of behavior from rednecks, but not from the sons of doctors, lawyers, and businessmen like our parents. I was news editor of The Sewanee Purple, and a group of us at the paper got busy and put out a special edition condemning the incident and its perpetrators. The rhetorical tone of what we wrote was pretty sophomoric and overblown, but we made our point.

In terms of our positive goals, our first aim was to integrate The Sewanee Inn, because in the rare instances when Black visitors came to the Mountain (as people still call the Sewanee campus), there was no place for them to stay. The inn’s proprietor, Miss Clara Shoemate, was, like Dr. Edward McCrady, whom you will meet shortly, just as nice as she could be, up to a point. Miss Clara’s chess pie was the best I’ve ever tasted, and she was a doting, protective mother figure to a lot of us boys, who ate at her restaurant when we could afford it. But you’d know I was lying if I told you she had cold Cokes sent out to us as we picketed her restaurant. She was an over-my-dead-body segregationist who stood at the door of her Sewanee Inn as resolutely as Governor George Wallace stood at the door of Foster Auditorium at the University of Alabama.

I was a member of the Sewanee Jazz Society, and in 1960 we did ourselves proud by being one of only two or three venues in the South that declined to cancel a concert by Dave Brubeck when he not only announced that his band was an integrated group but also insisted that admission had to be open to everyone. We hadn’t succeeded in getting the inn integrated yet, so Myles put Brubeck and his musicians up at Highlander. As they drove down from Nashville, they were confronted along the highway with a billboard showing a classroom at Highlander full of both white and Black students, with Dr. King in the front row, and emblazoned with the caption, MARTIN LUTHER KING AT COMMUNIST TRAINING SCHOOL. Brubeck asked his band members, “Did you fellows bring your cards? Don’t you know you can’t get in there unless you’re a card-carrying Communist?”

I don’t know if you can imagine what Dave Brubeck playing an out-of-tune old upright piano would have sounded like, but that’s what he did at Highlander—good-naturedly, too, incorporating the wrong notes into his improvisations. Joe Morello, behind the coke-bottle-thick lenses of his glasses, quietly whisked his brushes over his snare drum, and Eugene Wright resonantly plucked his stand-up bass. Paul Desmond’s tone on the alto saxophone has been likened to the taste of a dry martini, but that night he blew his horn out through the oaks and hickories around the Highlander Folk School as clear and sweet as Tennessee whiskey.

In 1961, when we hosted the Modern Jazz Quartet, Vice Chancellor (as the president at Sewanee is called) Edward McCrady offered to give a party for the ensemble. An Oak Ridge scientist and devout Episcopalian, a Renaissance man who was as comfortable translating Latin poetry as he was playing the cello, an amiable and distinguished man in almost every respect, our vice chancellor also happened to be a dyed-in-the-wool segregationist. According to Gardiner H. Shattuck, in Episcopalians and Race: Civil War to Civil Rights,

No one was more determined in his racial views than the newly appointed vice chancellor, Edward McCrady. McCrady belonged to a family that was “proudly Charlestonian.” … True to the patrician heritage in which he had been raised, McCrady maintained that “the salvation of any Negro soul is as important to God” as the eternal destiny of a white person, but he questioned the intellectual abilities of African Americans and saw no benefit in social interaction between the races.

But as he entertained the MJQ, members of the Jazz Society, and other guests at his spacious residence, Fulford Hall, Dr. McCrady didn’t let his prejudices interfere with his hostly duties.

To understand the level of racial ignorance in the Jim Crow South 60 years ago, you need to know that the only African Americans many of us encountered as white middle-class southerners from cities like Birmingham, Nashville, Atlanta, and Memphis were folks who cooked for us, looked after us as children, cut our hair, butlered, raked our leaves, and if we happened to be rich (which my family was not), chauffeured the family Packard. They were “like members of the family,” we would state smugly and obliviously.

So here we were at Sewanee, undergraduate jazz fans and our faculty sponsors, drinking cocktails with the Modern Jazz Quartet. Suzy had flown up from Texas and was at my side in the “little black dress” of the day. John Lewis—the jazz great, composer, pianist, and leader of the MJQ—and his colleagues were men who wore Italian suits and handmade shoes, who could order a meal in French and play Bach as easily as they could play Duke Ellington. They paid us the compliment of not condescending to us, no matter how provincial I’m sure we seemed to them. I think they actually liked us! We must have come across as charming exotics. Percy Heath was one of the kindest and most gracious men I ever met. I was delighted when it fell to me to drive him to the airport in Chattanooga the day after the concert in a friend’s MG. I wanted to talk about the civil rights movement; he wanted to tell me about the quartet’s recent trip to Venice.

Little did I know of class distinction in the African-American community back then. I suppose I first got glimpses of it at that long-ago cocktail party at Fulford Hall. Moving in and out among the guests with trays of drinks and canapés were Dr. McCrady’s house servants, several of whom were descendants of the formerly enslaved house servants who had followed their former masters, Confederate officers and their wives, when they returned to the Mountain in the late 1860s after the war. In the chaos of the post-emancipation South, when freed slaves took to the roads in a desperate search for employment off the plantations, these freedmen were lucky to be in a place like Sewanee, rather than in Birmingham, Montgomery, or the Mississippi Delta. To see the glances exchanged between those white-jacketed waiters and John Lewis, Percy Heath, Milt Jackson, and Connie Kay of the Modern Jazz Quartet was a study in class worthy of the pages of Marcel Proust.

But there was music on and around the Mountain of a different genre than jazz played by elegantly groomed men in striped trousers and morning coats. Guy Carawan made musical connections with every kind of picker and singer around. No one could be less like C. T. Vivian than Hamper McBee. Hamper was a moonshiner, bootlegger, heavy drinker, heavy smoker, sometime short-order cook and carnival barker, as well as a renowned balladeer. He wasn’t a folksinger out of the Pete Seeger–Greenwich Village mold; he was the genuine article, a rascally, ornery cuss who had grown up in the hollers around Sewanee.

Guy backed Hamper up on his Prestige record, Cumberland Moonshiner, which mixed traditional standards like “Good Old Mountain Dew” and “Wreck of the Old 97” with Grandpa Jones’s “Methodist Pie,” as well as the old English ballad “Henry Martyn,” which Hamper learned from a Joan Baez record at Highlander. I remember watching him play the cut from that Vanguard LP over and over again as he tried to learn the lyrics. When Guy asked him why he had always sung unaccompanied before then, Hamper replied, “Well, Guy, tell you the truth, I never could get nobody else to play with me.” Getting to know Black musicians at Highlander was as much an education for Hamper as it was for the rest of us.

I hung with Hamper both at Highlander and at fraternity parties in Sewanee, where he sold moonshine to the frat boys. He was famous for having ridden a mule up the stairs at the Kappa Sigma house, my fraternity house. Once they got the animal upstairs, nobody could get it down. If you know mules, you know that though a mule will climb stairs, it won’t come down again. I can’t remember how we ever got it out of there.

The last time I saw Hamper, I visited him in his double-wide trailer back behind Monteagle, shortly before his death from emphysema or lung cancer more than two decades ago. Hamper had always sported a handlebar mustache that would put a Harley-Davidson to shame. But on this occasion, I found that he had shaved off one side of the mustache. That way he could get oxygen from the tank that sat beside the decrepit recliner where he lounged, while at the same time sipping malt liquor from tall boys and turning the oxygen off so he could smoke Pall Malls, accompanied by horrendous bouts of wheezing and coughing.

Suzy and I live most of the year in Hawaii now, but we found a way to buy a little summer place for ourselves back in Sewanee. Living in Europe and Hawaii has taught me that however great the charms of foreign cultures, my truest connections are with the place where I grew up—visiting with my home folks in Tennessee and the Delta, listening to fiddle music or the blues, sitting around the holiday table with cousins, breathing the rich air of summer nights lit up with lightning bugs. After a few days below the Mason-Dixon Line, my southern accent comes back unsummoned. If you could taste my skillet cornbread, you’d swear I’d never left.

Much is the same, but much, thankfully, has changed. In 2020, the University of the South appointed its first Black vice-chancellor, something that would have been unthinkable when I was a student there. The United States elected and reelected our first Black president, a wise and inspiring man.

And yet, in the intervening years, mobs of white supremacists have marched through our cities by torchlight, and though we thought we were going forward, it appears the very opposite is happening, with all the old ugliness returning again. That white supremacy is on the rise is particularly troubling to those of us who are living in the last years of our lives. We managed to coax the mule up the stairs, and now they’re trying to force it back down again.

In the midst of these troubling thoughts, I ask myself what Suzy and I absorbed from our time on the fringes of the civil rights movement all those years ago. Suzy is a painter whose subjects are drawn from the indigenous cultures of Hawaii and other Pacific islands. I believe the respect and admiration she feels toward members of these cultures and the care she takes in documenting their lives derive to some extent from what she learned from African-American culture. As the novelist and essayist Marilynne Robinson has eloquently written, “It is true and always to be remembered that the great influx of Africans was a gift to the culture that has given it a brilliance and rich distinctiveness the whole world enjoys. That they came as captives and lived as slaves is an inexpressible grief and transgression.”

As for myself, I see the change in my attitudes about race as a process of opening, of becoming more fully human. Simplistic as that may sound, think about it. Many white southerners back in the ’50s and ’60s simply closed and opposed—people like Miss Clara at Sewanee and, in an uglier and more consequential way, Governor Wallace declaring in 1963, “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!” People like Suzy and me, Myles Horton, Guy and Candie Carawan, and all the other white allies and sympathizers were saying yes instead of no. That’s all. I’m not trying to give ourselves a pat on the back, but it was important because, at the time, so many people were saying no.

One thing that’s different in the South today, it seems to me, is the nuanced way in which Black and white people relate to one another. Even in the bad old days, these interactions seemed to take place more easily in the South than they did in the North, if only because of familiarity. As an octogenarian, I particularly enjoy my casual interactions with African Americans in my age group. There are certain benefits to being an old-timer. The conversations I find myself falling into now in Memphis and the Delta seldom explicitly touch on the subject of race. But it’s there. As we talk, you can feel an unspoken awareness and acknowledgment of all the history we have witnessed in our long lives. It’s interesting to me that so many African Americans have pulled up stakes in the North and, in a reverse migration, have moved back home. Like the hero of Gladys Knight’s song “Midnight Train to Georgia,” they’re “going back to find … a simpler place in time” in a “world [they’d] left behind.” Thank God that place has, to a degree, changed.

The civil rights movement was an African-American movement, with its own martyred leader, Martin Luther King. Myles Horton saw his role at Highlander as reminding members of this oppressed population of strategies they might use. Once he felt he had transmitted the essence of these ideas, he was content to repair to the sidelines, his job done, and let others work things out. Dr. King may have learned a lot about civil disobedience from Horton, but he also learned from Gandhi, Thoreau, and especially from the New Testament. Given his background in the church, probably Dr. King’s most heartfelt expressions of a nonreactive response to evil came from scripture. Jesus’s words were, “I say unto you, That ye resist not evil: but whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also.” And yet this kind of passivity does not fully describe Dr. King’s radicalism or that of the movement. A friend who used to write for the Nation of Islam’s paper, Muhammad Speaks, reminds me that Dr. King was a preacher who sometimes packed a gun and was surrounded by bodyguards with guns, prepared to defend both him and themselves.

The State of Tennessee shut Highlander down in 1961 for selling alcohol without a license. Evidence for the “illegal” alcohol sales was that honor box next to the icebox to replenish the beer fund when someone took out a beer. Undeterred, Highlander, now called the Highlander Center, relocated to a site in New Market, Tennessee, 20 miles east of Knoxville, where its emphasis shifted to Appalachian issues. In April 2019, a fire set at the center destroyed its main building, and a white nationalist symbol was found nearby. Segregationists and white supremacists have always tried to destroy the school. They recognize the force of its mission and message.

The year before Guy died, Suzy and I drove over from Sewanee to visit him and Candie in their log cabin at the “new” Highlander. We had some good visits there on their porch, four old-timers talking about old friends and looking back at the history we had witnessed together. Guy’s dementia was far advanced by then, and he had a hard time remembering the words to his old songs. I played a few tunes on his guitar, and finally one or two of the old songs slipped back into his memory and he sang them for us.

Where would the civil rights movement have been without “We Shall Overcome”? Anyone who was involved will remember holding hands, swaying to the music when we were surrounded by threatening enemies, and singing: “We are not afraid, we are not afraid, we are not afraid today.” The song said it for us and helped us believe it. When Bull Connor unleashed his police dogs in Birmingham, when John Lewis had his head cracked open by a policeman’s club on the bridge in Selma, when Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner were murdered that dark night in Mississippi, when Dr. King stood on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis a nanosecond before the fatal shot was fired, the same truth can be said to have resounded unspoken within all of them: “Deep in my heart, I do believe, we shall overcome some day.”