I had little incentive to see Todd Phillips’s Joker when it first appeared in the fall of 2019. A. O. Scott of The New York Times called it “weightless and shallow.” Richard Brody of The New Yorker said it was a film marked by “a rare, numbing emptiness.” I was never a great fan of Marvel or DC Comics and their monopoly on films about superheroes and supervillains. Batman, in particular, seemed humorless in all his incarnations. His butler, Alfred, when played by Michael Caine in Christopher Nolan’s three Batman films, was far more appealing. So I was prepared to leave Phillips’s Joker behind. But I had long admired Joaquin Phoenix and his quirky performances, and I have always been nostalgic about Batman’s Gotham City, a funhouse mirror of Manhattan, where I, a Bronx native, have been living on and off for the past 50 years.

The film I watched at a Cineplex on West 23rd Street was not “a story about nothing,” as Scott had declared with such disdain. It was a disturbing tale of our time, depicting the numbing darkness of an America that had itself become a surreal cartoon, where billionaires live in gated, fortresslike manors while millions struggle to survive. Batman’s father, Thomas Wayne (Brett Cullen), is the DC Comics version of a superrich American, and when he refers to Gotham’s rabble as “clowns,” he seems to summon up Arthur Fleck, who morphs into Joker in the middle of the film.

Arthur is a party clown and a novice standup comic who longs to be discovered by Murray Franklin, a late-night show host played by Robert De Niro. Arthur lives in a shabby apartment with his mother, Penny Fleck (Frances Conroy), who is both disabled and delusional. Having once worked as a housekeeper at Wayne Manor, Penny has been writing to Thomas Wayne, asking for help. When Arthur happens to read one of these letters, he confronts his mother, who confesses that she and Thomas had been lovers and that Arthur was their secret child.

In the film’s most poignant moment, Arthur goes to Wayne Manor and stands in front of its unwelcoming prisonlike gate. He tries to entice the young Bruce Wayne (Dante Pereira-Olson)—his supposed little half-brother and the future Batman—by performing magic tricks, but the churlish butler, Alfred Pennyworth (Douglas Hodge), cruelly sends him away. Undaunted, Arthur goes to a benefit at Wayne Hall, hoping to confront his father. He sneaks in, wearing an usher’s uniform. Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936) is playing on the big screen, and we see a curious resemblance between Chaplin’s Tramp and Arthur Fleck. Both are clowns, both members of the downtrodden underclass. Both films depict worlds in which the rich are devourers and the poor have no choice but to rebel. But where Chaplin’s comic character is touching and inventive, Arthur is a failed comedian in a failed town. All social services have been cut in Gotham. Arthur is denied his meds. Whatever creative spark he had is gone, his growing mental instability having led the way to violence.

Arthur follows Thomas Wayne into a lavatory at Wayne Hall. Thomas is completely cold to this “lost son” and punches him in the face, insisting that he was adopted and that Penny had to be locked away at Arkham State Hospital. Arthur goes to Arkham and makes off with his mother’s file. He discovers that one of Penny’s boyfriends had tortured and sexually abused him as Penny stood by.

By this point, Arthur has already crossed the line into madness and mayhem. Earlier, while wearing his clown costume on the subway, he encounters three drunken stockbrokers from Wayne Investments who are annoying a helpless young woman. When he catches their attention, the three brokers kick and punch him. But Arthur is armed with a gun and murders all three in cold blood. Immediately he is revered by the masses as Gotham’s notorious “Killer Clown.” In an instant, Joker is born.

With Gotham in the middle of a crippling garbage strike and the metropolis flooded with giant rats, the city’s disaffected now put on Joker masks and set fire to every car they find. Meanwhile Penny has had a stroke and is in the hospital. With Joker’s venom in him, Arthur smothers her with a pillow.

In one of the film’s iconic scenes, we see Arthur in his clown’s painted face dancing down a towering street of stairs. This bit of Gotham is actually located in the Bronx—the stairs link Shakespeare and Anderson avenues in the Highbridge neighborhood—and today, those so-called Joker Stairs are visited by fans from all over the world. In my childhood, I clambered up and down this same hilly street of stairs every day. I climbed with magic in my head, imagining myself as a pirate conquering the Kingdom of Highbridge. When I saw this location being used in Joker, I felt as if Phillips had appropriated my stairs. But I could also sense the full lyrical force of the film as Joker dances down the steps, with Phoenix capturing the sense of sudden, maddening joy. No other actor could have played Arthur Fleck with the same consummate skill. The haunting musical score by Icelandic composer Hildur Guðnadóttir adds a note of deep sadness and a spark of humanity to murderous Arthur, who will end up at Arkham among the criminally insane.

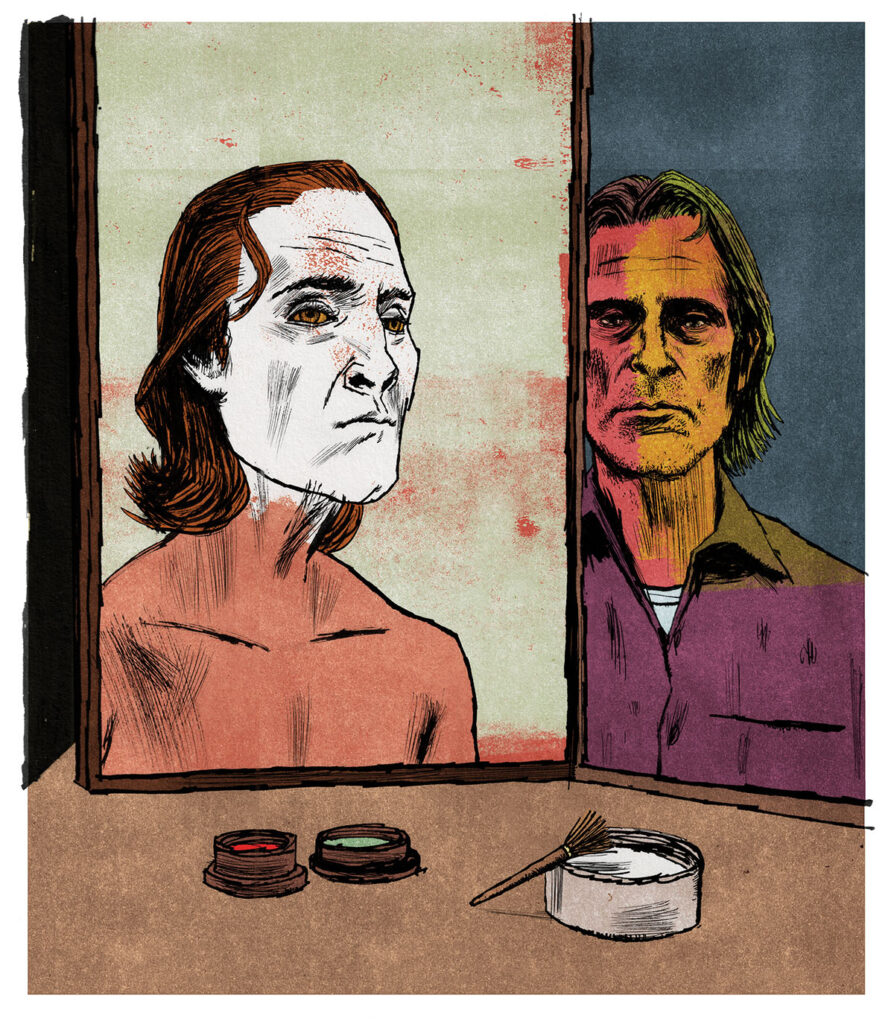

Joker isn’t the usual villain origin story. Among Batman’s gallery of villains, Joker stands alone. Some critics see Martin Scorsese’s fingerprints all over Phillips’s film and have even accused the director of stealing from Taxi Driver (1976). Travis Bickle, played with a frightening allure by a much younger De Niro, is a crazy man in a sane world. (Scorsese also cast De Niro as a standup comedian in the 1982 film The King of Comedy.) But Arthur’s craziness is much closer to us. We can identify with his pain—with the howl inside his head—and sympathize with his plight in a way we do not with Travis Bickle and his Mohawk haircut, his moodiness, and his desire to maim and kill. Arthur is Chaplin’s Tramp gone awry. Today, Thomas Wayne seems more of a villain than Joker, and not only because of his billions. He cares nothing for Gotham’s residents, whom he seeks to govern as mayor.

Joker was a success worldwide, the first R-rated movie to gross a billion dollars. So what can explain the absolute failure of its sequel, Joker: Folie à Deux? Was it because the movie was released so close to the 2024 presidential election, which left half the country in a state of hysteria? There was a certain dread at the film’s New York premiere, a concern that the film would incite audiences to wreak havoc on Manhattan. But pandemonium did not break out. The only commotion was a dead firecracker, like the film itself.

Yet the sequel had seemed destined for success. Phoenix returned as Joker in Folie à Deux, accompanied by Lady Gaga as Lee Quinzel, the cocoon of another arch villain, Harley Quinn, a Joker groupie who happens to be a pyromaniac. It’s a noir love story that should have ignited audiences. But Folie à Deux fell flat. The décor turned out to be all wrong. Much of the story takes place in Arkham State Hospital, but this isn’t the diabolic asylum of comic book fame, filled with an assortment of Batman’s enemies and other maniacs. The Arkham of Folie à Deux isn’t frightening in the least. It seems more like a community college than the hellhole it should have been. Arthur has no momentum here.

Phillips, who directed the sequel, asserts that Folie à Deux is not a musical, but the film’s 16 musical numbers, such as “Gonna Build a Mountain” and “That’s Life” (sung by Frank Sinatra), often destroy the film’s narrative flow. Lady Gaga is very good as Lee, a rich girl who pretends to be poor, who has herself committed to Arkham so that she can be near Joker. But she drops him the moment he gives up his alter ego and becomes Arthur Fleck again, leaving the audience with no one to love.

That all changes in the film’s last 15 minutes. Suddenly we feel Arthur’s pain. He sings “If You Go Away” to Lee while on the prison phone, like a poet rather than an ex-clown. Then a psychotic inmate stabs him repeatedly in the stomach with a shiv. As Arthur lies dying, the inmate carves a smile on his own face with the shiv and becomes the next Joker in line, with a brand-new origin story, unknown to us.

In his dismissal of the earlier Joker, Richard Brody wrote that Arthur “isn’t so much unhinged as unmotivated and, to all appearances, undirected.” Never mind that Phoenix received an Academy Award for his portrayal of Arthur Fleck. Awards may not mean that much, but audiences were still rhapsodic about him. Phoenix carried Joker. He is the film. Perhaps he directed himself. If his performance seems unhinged at times, it’s because the world around us feels increasingly unhinged. He’s more linear in Folie à Deux and far less convincing. The landscape narrows as we move back and forth between Arkham and the courthouse where Arthur stands trial for the murders he has committed.

Brody trashes both Joker films, and he believes that Phillips deals in a fashionable commodity “called darkness.” But he ought to look again. That darkness resides in Phoenix’s skeletal frame, in his birdlike bones. Joker frightened me. Arthur’s disjointed persona felt exactly like mine. I’m not a murderer. But I might have become one had I been tied to a radiator and beaten while my mother watched. In spite of his bleeding to death on Arkham’s floor in Folie à Deux and the end of his reign as Joker, Arthur still persists as a 21st-century Everyman, with memories of a clown’s green wig, his bag of tricks, and his masterly dance on a street of stairs in the backwaters of the Bronx.