When I was a graduate student at the University of Kansas, I lived in a rented farmhouse and owned a horse. I knew people enrolled in the Pearson Integrated Humanities Program, a curriculum based on classical Greek and Roman texts. Some students, inspired by their readings of Theocritus and Virgil, decided to spend a semester at a farm in Marysville, Kansas, where they would live close to the land. They also thought they should farm with horses—genuine horsepower. I boarded a horse for my friend Eva Tarnower, who was part of the humanities program, and another for John McDonald, who later founded Boulevard Brewery. The three of us agreed to loan our horses to the program for a semester. We weren’t sure they would return better educated, but they’d certainly be well used.

We chose the traditional way to transport the horses 150 miles to the farm: we’d ride. So, in the late summer of 1973, we set out with bedrolls, my guitar, a small amount of cash, and a couple changes of clothes each: Eva on her horse Flower, her friend Roger Williams riding John’s mare Jo, and I on my little Morgan/Shetland horse Cuck. We were relying on the kindness of strangers for pasture, food, and barns to sleep in. And rural Kansans were generous: we were well-fed and slept mostly in beds; our horses were given grain and shelter. We didn’t need to spend our cash. As Roger speculated about those Kansans, “They were people who may have been startled to see three riders on horseback, one with a guitar, appear in their barnyards out of the heat on a late August afternoon, but they did not feel like aliens had just arrived. Because horses and music were things they grew up with, or their parents did.”

The trip took five days. Our singing helped us through the long hours. We entertained one another, and, since we’d vowed never to repeat a song, covered plenty of musical terrain: songs from our childhoods, church hymns from three denominations, Boy and Girl Scout songs, camp songs, along with folk songs, blues, ballads, and shanties. We learned about our respective musical traditions, and even more about one another.

Several songs I offered were by Robert Burns. “Auld Lang Syne,” of course: most everyone has the chorus and a couple of verses by heart. But also “A Red, Red Rose,” and what in our family was its companion, “The Henpecked Husband.” My brother and I had written music for both, since we didn’t know that Burns composed them as songs, and I still like our compositions, even after I have become intimately acquainted with Burns’s affinity for music. Scotland’s Bard spent the first half of his life as a poet who also wrote songs and the second half as a collector and writer of songs who also sometimes wrote poetry. Burns was part of our family culture, as was music. The Carsons, my grandmother’s family, sailed from Dalbeattie to Massachusetts, where she was born in 1890, then to Vermont, to California (where my father was born in 1924), and finally to Kansas. When I sang Burns songs on that 150-mile horse trip, I did not know that he himself recited and composed on horseback, whole songs like “Saw Ye Bonnie Lesley” taking shape in a several-hour journey. But even his poems are rooted in motion, in music. Burns’s first poem, “O Once I Lov’d,” or “Handsome Nell,” was inspired by music that was beloved by his beloved. He was around 15 years old, enamored of Nelly Blair (some say that her name was Nelly Kirkpatrick), a year his junior. She was paired with him in the harvest fields; most likely he cut the barley with a sickle, and she tied it into sheaves. “Among her other love-inspiring qualifications, she sung sweetly,” he wrote in a letter, “and ’twas her favourite reel to which I attempted giving an embodied vehicle in rhyme.”

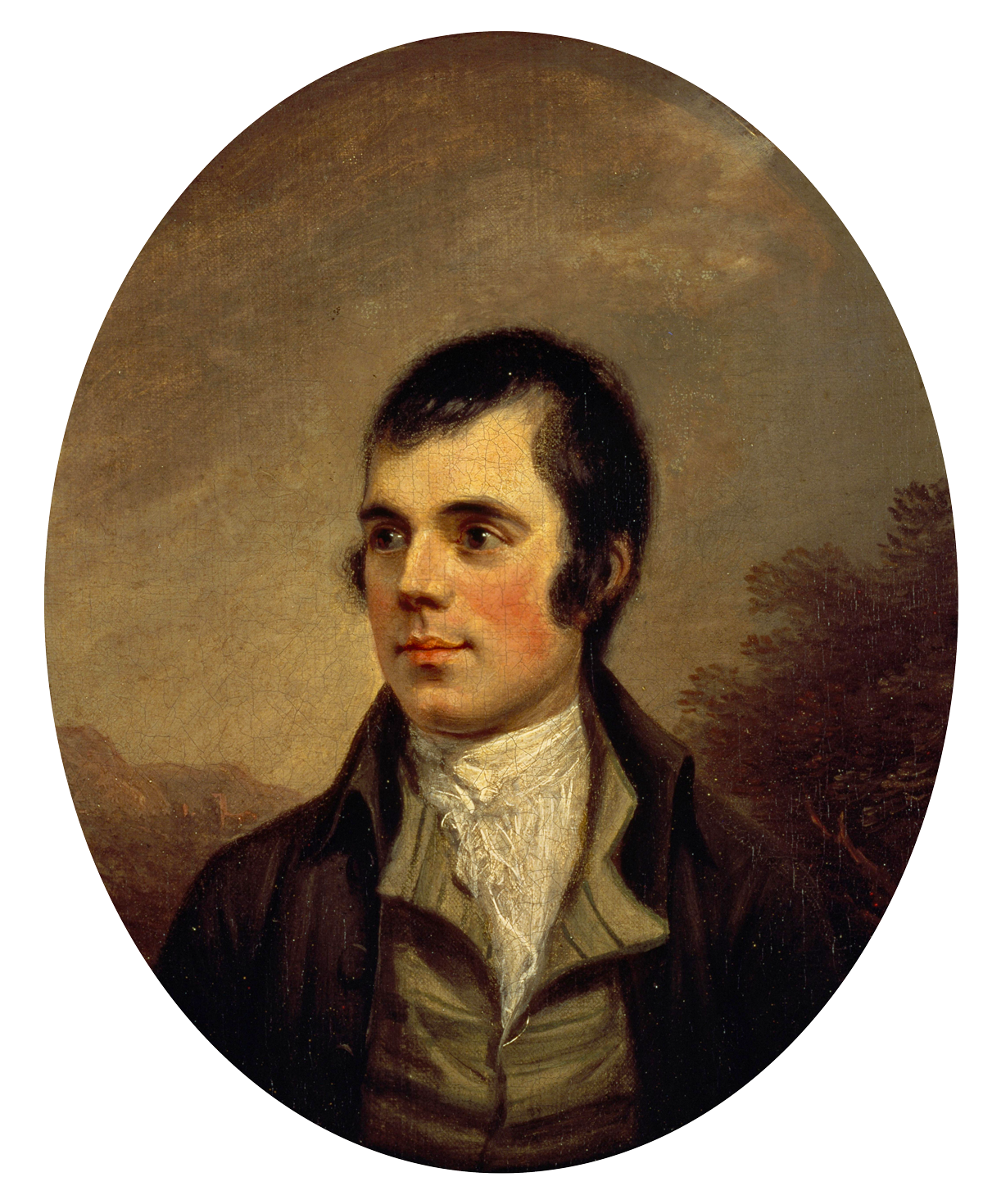

Portrait of Robert Burns by Alexander Nasmyth, 1787, Scottish National Portrait Gallery

Burns grew up with a mother who sang to him, as my father did, and as I did. (My grandmother sang Burns to my father when he was a boy, playing “Tam O’ Shanter” for him on the piano.) Burns lived in a rich oral tradition, albeit one under threat. The British were clearing the Highlands, enacting laws against clans, prohibiting the wearing of tartans and the playing of bagpipes and exorbitantly taxing the sale of whisky. There was pressure to speak “proper” English, and Burns was admonished not to write his poems in the Lowland Scottish Dialect natural to him. But his stubborn attachment to Scots language and culture is revealed in the title of his first published book, Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect (the Kilmarnock Edition of 1786).

The book won him immediate fame in Edinburgh, where he stayed for a time, working on an expanded Edinburgh Edition. There, he met James Johnson, who was preserving the nation’s traditional tunes and songs in The Scots Musical Museum. By May 1787, Burns was contributing songs. One biographer notes that some of the traditional songs, without his sympathetic touch, “would probably have been lost.” Beyond collecting them and often tweaking lines, he also wrote his own lyrics, creating songs so artful that the tunes would become part of Scotland’s legacy. Burns collected avidly during 1787, when he set out on three tours of Scotland, to learn its history, hear its legends, and behold its natural beauty.

In all, Burns contributed around 177 songs to the Musical Museum. Of the process, the Canadian scholar of Scottish literature G. Ross Roy writes,

The craftsman in Burns refurbished a good deal of what he came across in the oral tradition, rounding out a line, supplying a better line, sometimes using only a fragment of the original to be incorporated in a complete song. In this sense Burns was a creator, not a conservationist—his concern was to leave the world a work of art.

Burns was, according to Gerard Carruthers of the University of Glasgow, “on a national mission to foreground the song traditions of his nation at a time when there were fears this tradition was dying out and might be forgotten.” Burns was like John and Alan Lomax—who traveled the South collecting folk songs, blues, and ballads—but without recording devices.

Burns contributed to another gathering of Scottish music, George Thomson’s Select Scottish Airs, sending Thomson at least 114 songs between 1792 and 1796. He’d promised more, but the poet was sickly by then, and in April of 1796, a few months before his death from bacterial endocarditis, a complication of rheumatic fever, he wrote to Thomson: Alas! … I fear it will be some time ere I tune my lyre again!

My parents thought no home should be without a piano, and they insisted we four children take lessons. I dropped piano early and took up the trumpet, which I duly dropped for the guitar in college. My father, though he did not have a stunning bass voice, sang in the church choir. My mother, a music enthusiast who lacked strong vocal skills, participated in the Bell Choir. Years later, I think of their commitment to enacted, communal music. As Burns writes in “The Cotter’s Saturday Night,” they were hymning together their creator’s praise, my father chanting his artless tones in simple guise, my mother, bell raised, ringing out the heavenward flame.

In the 1980s, I followed my father in learning to play the Great Highland Bagpipes, which we played together in his band, the Pipers of the Plains. Mastering the pipes and the music was not easy, if master it I ever did. All tunes must be memorized; some pipers have a thousand stored in their brains. At my peak, I had perhaps a hundred.

Some tunes, though I didn’t know it at the time, were those used by Burns as the melodies for his songs. “Auld Lang Syne”—Old Long Since—is one of the oldest, and every piper must know it for Hogmanay, the Scots celebration of the last day of the old year. The first tune any piper learns is now called “Scots Wha Hae,” but it’s a traditional Scots air, “Hey Tuttie, Tatie,” a tune reputed to be the one pipers played as they went into battle under the command of Robert the Bruce. Burns titled his song “Robert Bruce’s March to Bannockburn,” an imagining of the impassioned address Bruce made to his troops before that victorious battle of 1314:

Lay the proud usurpers low!

Tyrants fall in every foe! Liberty’s in every blow!—

Let us do, or die!

My father and a friend had originally formed the Pipers of the Plains hoping to march in Topeka’s 1976 St. Patrick’s Day parade. They succeeded, and my father played in that parade until 1996, the year he died. After his death, I wrote a pipe tune for him, “The Stuart Averill.” I have continued to write tunes for family and friends, some three dozen so far.

The Scots Musical Museum and Select Scottish Airs preserve Burns’s work, with lyrics and music in print. But songs spread as much through performance and memory as by notation and text. Songs are perhaps the most portable poetry, easily carried from place to place. In the popular mind, Burns was known as much for song as poem. According to Ferenc Morton Szasz, in Abraham Lincoln and Robert Burns, “the poet reached countless early-nineteenth-century Americans largely through the power of his songs.” They were so well-known that they were used to propagate political and social ideas. African-American poet and abolitionist William Wells Brown rewrote Burns’s “A Man’s A Man For A’ That” as “The Slave’s A Man, For A’ That”:

Though stripped of all the dearest rights

Which nature claims and a’ that,

There’s that which in the slave unites

To make the man for a’ that:

For a’ that, and a’ that,

Though dark his skin, and a’ that,

We cannot rob him of his kind,

The slave’s a man, for a’ that.

This and other adaptations of Burns’s songs, one by Henry Lloyd Garrison, were included in Brown’s Anti-Slavery Harp: A Collection of Songs for Anti-Slavery Meetings.

At the same time that the work of the Lomaxes jump-started folk music revivals in America, a similar revival was happening in the UK. In 1964, the Scottish folk singer Jean Redpath came to the United States with $11 in her pocket and began performing in San Francisco. She built her reputation singing 400-plus songs she’d learned through tapes and discs collected by the School of Scottish Studies in Edinburgh. She later met Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and Bob Dylan in Greenwich Village and became a fixture in the folk music scene.

In 1976, Redpath set a goal to record all of Burns’s songs in a 22-volume set—another musical museum. But that project ended after seven volumes, with the death of her musical collaborator, Serge Hovey, in 1989. Redpath later created four more volumes, singing Burns a capella. The 75 Hovey arrangements range from the sentimental (“A Red, Red Rose”) to the political (“A Parcel of Rogues in a Nation”) to the lamentation for lost love (“Banks O’ Doon”) to the celebration of love and lasses (“Green Grow the Rashes, O”) to the bawdy (“Nine Inch Will Please a Lady”). Each is rendered true, Redpath’s powerful voice full of whatever emotion is called for: reverence, chastisement, sadness, playfulness, lust, friendship. I’ve committed all but the raunchy “Nine Inch” to memory, along with several others that Redpath sings so movingly. And, of course, that song of global New Years tradition: “Auld Lang Syne.” Burns knew of its origins in an anonymous poem from the 15th century.

As he wrote to George Thomson:

One song more, and I have done, Auld lang syne. The air is but mediocre; but the following song—the old song of the olden times, and which has never been in print, nor even in manuscript, until I took it down from an old man’s singing—is enough to recommend any air.

Other Scottish writers, including Allan Ramsay, had worked with this same material. But once published by Thomson, and then by James Johnson in his Scots Musical Museum, Burns’s “Auld Lang Syne” would not be changed. In his copy of The Scots Musical Museum, Burns wrote in the margins:

The chorus of this is old; the rest of it is mine. … Here, once for all, let me apologize for many silly compositions of mine in this work. Many beautiful airs wanted words; in the hurry of other avocations, if I could string a parcel of rhymes together anything near tolerable, I was fain to let them pass. He must be an excellent poet indeed, whose every performance is excellent.

Despite Burns’s self-effacement, his song is elegant, touching, and tugs at our desire to reunite in the music that brings us thegither. It is written almost exclusively with one-syllable words, powerful in their repetition. In his efforts to save Scottish music, Burns wrote artful verse that embraced not only all of himself, but all of Scotland, too.