Reading The Story of the Lost Child, the final work of Elena Ferrante’s extraordinary quartet of Neapolitan novels, I was swept away as I haven’t been since I first read the great Victorians and Russians. Now published in English by Europa Editions, Ferrante’s unflinching anatomization of the complicated friendship across 60 years of two girls from Naples is set against a landscape of social upheaval counterpointed by the unyielding forces of the status quo. Yet her books are utterly contemporary, impossible to imagine before the feminist revolution encouraged women to write openly of their conflicted feelings about men, motherhood, and ambition and its attendant anxieties.

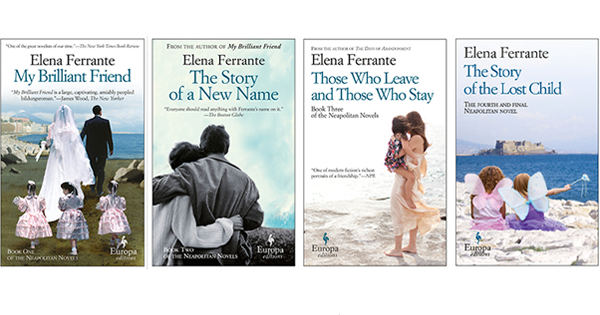

My Brilliant Friend (2012) takes place during the 1950s, as the 66-year-old narrator looks back on her childhood in a violent, impoverished Neapolitan neighborhood. Elena Greco, known as Lenù, revisits those days, for which she has no nostalgia, provoked by her friend Lila (full name Raffaella Cerullo). She has vanished from Naples along with all her possessions, fulfilling a decades-old desire “to disappear without leaving a trace.” Lenù is infuriated by Lila’s attempt to eradicate their shared past and deny the significance of a life that has been a shadow sibling to her own climb into the middle class as a successful writer and feminist pundit. “We’ll see who wins this time,” she thinks, as she begins to set down their story.

The structure may owe something of its freedom to modernism, but Ferrante’s prose, perfectly translated by Ann Goldstein, is blunt and direct, the tumble of events worthy of the most lurid potboiler. “I renounce nothing that can give pleasure to the reader, not even what is considered old, trite, vulgar,” Ferrante said in a recent Paris Review interview that provides cogent insight into her creative process. For all the murders, beatings, infidelities, savage quarrels, and verbal cruelty that scar their pages, the Neapolitan novels indeed offer abundant pleasure: the pleasure of truth.

And yet, their narrator is not necessarily truthful. Lenù’s pronouncements about Lila and herself can’t always be trusted; we see that she doesn’t entirely know what her true feelings are. But we trust absolutely the truthfulness of the sentences in which Ferrante sets down those tangled feelings, the lucidity of her vision of a world where even the most intimate relationships are about power: who has it, who resists it, how it can pass from one group to another without life’s basic inequities ever changing. Within the neighborhood, power is wielded primarily by men over women and by the mobbed-up Solaras, whose loan-sharking and other crimes make them local stand-ins for the corrupt politicians who rely on their strong-arming for elections.

The Solara brothers, Marcello and Michele, flaunt their status in My Brilliant Friend by pulling a pretty girl into their expensive car and returning her later, ruining her reputation in this sexually repressive society. When they try to do the same to 13-year-old Lenù, breaking the silver bracelet her mother has allowed her to wear as a reward for her good grades, Lila holds a knife to Marcello’s throat and says coolly, “Touch her again and I’ll show you what happens.” The hatred and respect Lila provokes in the Solaras will drive major portions of the plot in all four novels; the bracelet will become a talisman of of Lenù’s stormy bond with her mother, making a poignant appearance at Immacolata Greco’s deathbed in The Story of the Lost Child. The superb development of images and metaphors in Ferrante’s text, from the first chapter to the last, some 1,600 pages later, is deeply satisfying.

Their encounter with the Solaras underscores the contrast between Lenù and Lila. Both girls are smart. Lila is the bold, quick-witted one who learns effortlessly, draws her own conclusions, and revels in challenging authority. Lenù is the dutiful student who works hard, forever seeking the right answer that will please her teachers. Lenù goes on to high school; Lila disdains further education and turns to designing stylish shoes she believes will transform the modest family shoemaking shop into a money-making enterprise. Their girlish dreams of writing novels won’t give her the clout she wants, she tells Lenù: “To become truly rich you need a business.” At 16, Lila marries the son of another local big-shot who offers to finance the production of her shoes.

Lila the risk-taker, the brave antagonist of brutal men, can’t imagine a life for herself outside the neighborhood. While she strives first to manipulate its power structure, then to defy it in The Story of a New Name, Lenù hesitantly and fearfully crosses its borders to attend a free college in Pisa. She’s still trying to say what those in charge want to hear, but now it is her left-wing professors and her wealthy Communist boyfriend she caters to. She will never have the creativity of thought, she thinks despairingly, with which Lila has enchanted Nino Sarratore, the studious neighborhood boy Lenù has loved since childhood. Lila’s affair with Nino breaks up her marriage but doesn’t get her out of Naples; at the novel’s close, she’s working in a sausage factory and claims not to remember the story she wrote at age 10 that Lenù brings to the factory to remind her of their youthful aspirations. “That’s where my book comes from,” she tells Lila. Lenù has graduated with highest honors, and her first novel is about to be published, but she still thinks Lila is the brilliant one.

What Lila thinks is more opaque, because we see her through Lenù’s eyes, but their charged conversations over the years reveal on both sides a combustible mix of contradictory sentiments: admiration and envy, competitiveness and solidarity, profound intimacy and bitter alienation. I don’t know of a franker, more nuanced, more complete rendering of female friendship in modern literature—or any literature.

The crux of their relationship is defined in the third volume’s title, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay. When Lenù leaves, marrying into a family of socially prominent northern Italian academics, she experiences the political turmoil of the late 1960s and ’70s as a young mother in Florence struggling to balance writing with the demands of her children; a feminist essay on “the invention of women by men” solidifies her stature as a public intellectual. Back home, Lila participates in the political extremism that sends two of their childhood friends into the terrorist underground, then pulls back to enter the brand-new business of computers with another childhood friend, who becomes her devoted partner after Nino seemingly abandons her. The thick weave of neighborhood connections continues to enfold Lenù, especially when Nino reenters and upends her life. But now she is an outsider, her accomplishments mostly ignored or resented by the people she grew up among, while Lila remains one of them.

The Story of the Lost Child takes their friendship into new territory by bringing Lenù back to Naples, a paradox that exemplifies Ferrante’s command of—and comfort with—ambiguity. An electrifying early scene simultaneously explicates a mysterious subterranean strand in the three previous novels and calls into question everything we think we have learned about Lenù and Lila. The two women, both pregnant, take refuge in Lila’s car during the earthquake of 1980. Lenù is reasonably calm; Lila is beside herself. A searing monologue reveals the fear she has concealed for a lifetime. Lila, the master of every neighborhood intrigue, the cynical realist who never tires of scornfully demonstrating how little Lenù knows about how the world really works, is terrified by reality. The physical universe is for her a place of “dissolving boundaries” where objects melt and reform in hideous shapes that reflect “the disquiet of my mind.” Lenù, whose narration has laid out her every uncertainty and insecurity, turns out to be the stable one who has constructed a workable identity: “Elena Greco, the brilliant friend of Raffaella Cerullo.”

Or is she? In middle age, devastated by a horrific loss, Lila begins to write again, a vast history of Naples that casts the city she has never left as the incarnation of her personal instability: “a cyclical Naples where everything was marvelous and everything became gray and irrational and everything sparkled again.” Lenù, whose career is no longer going well, trembles in anticipation of being shown up as the shallow imitation of her brilliant friend. What if Lila has finally written a masterpiece that demonstrates “how I should have written but had been unable to,” she asks. “From that unexpected reversal of destinies I would emerge annihilated.”

The manuscript vanishes along with Lila. Her parting gift to Lenù is a memento of the day they became friends, a reminder that once again we have not wholly understood everything we have seen. “Unlike stories, real life, when it has passed, inclines toward obscurity, not clarity,” Ferrante reminds us. The Neapolitan novels, dense with the weight and texture of real life, nonetheless bear the palpable imprint of an artist.