The Old Master

Neville Marriner breathed new life into Baroque music, with a sense of drive and panache

Had you turned on the radio to any classical music station in the 1970s or ’80s, chances are you would have heard, before too long, a recording by the Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields. No conductor at that time was more synonymous with the Baroque repertoire—the music of Corelli, Vivaldi, Handel, Telemann, and Bach—than the orchestra’s music director, Neville Marriner, whose stylish performances, full of charm, wit, and grace, were in stark contrast to the dour interpretations that were all too common before him. Marriner died in October, at the age of 92. And although he had turned over his day-to-day responsibilities as music director of the Academy to the violinist Joshua Bell five years before, the orchestra, formed in the sitting room of Marriner’s London flat in the late 1950s, will forever be associated with him.

He was born in the cathedral city of Lincoln, in the English East Midlands, to parents obsessed with classical music. His father, a carpenter by trade, was an avid—if, by Marriner’s reckoning, talentless—musician. He was also an effective teacher, and he encouraged his son to take up the violin and the piano. At the age of 15, Marriner moved to London to continue his violin studies at the Royal College of Music. But he realized soon enough that he lacked the chops to become a soloist, and after a period of wartime military service, he returned to the Royal College of Music, spent a year at the Paris Conservatoire, and decided to make a life not as a touring virtuoso but as an orchestral musician.

Following a stint in London’s Philharmonia, Marriner landed a prestigious job—principal second violin in the London Symphony Orchestra, a position he held until the late 1960s. It was a heady time at the LSO, with prominent instrumentalists bringing not only technique but also a strong temperament to many of the orchestra’s first desks—they had little interest in submitting, without question, to the will of an iron-fisted conductor. Marriner began to grow frustrated with orchestral life, and it wasn’t long before he was inviting a dozen or so colleagues to his home in Kensington to play through the classics of Italian and German Baroque music, repertoire in which he had taken a keen interest of late. The musicians played only for pleasure—no salaries were awarded at first—and from the start, the spirit was decidedly democratic. “We needed to earn a living, and playing in symphony orchestras was a way of making that happen,” Marriner once said, “but I think we all felt at the time that we didn’t have enough individual responsibility for the product.”

The group’s keyboard player, John Churchill, suggested that the musicians might present a concert at the church where he happened to be both organist and music director: the stately Georgian edifice commanding one corner of Trafalgar Square and known as St. Martin-in-the-Fields. The musicians needed convincing, but the five performances they ended up giving during the 1958–59 season were so well received that more concerts were scheduled. The first of the orchestra’s recordings soon followed. The vicar of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, Austen Williams, cut the fledgling ensemble a deal: he would allow them to rehearse at the church at no cost, provided they took, and thus promoted, its name. At first, they were to be the St. Martin-in-the-Fields Chamber Orchestra. It was the vicar who insisted on Academy.

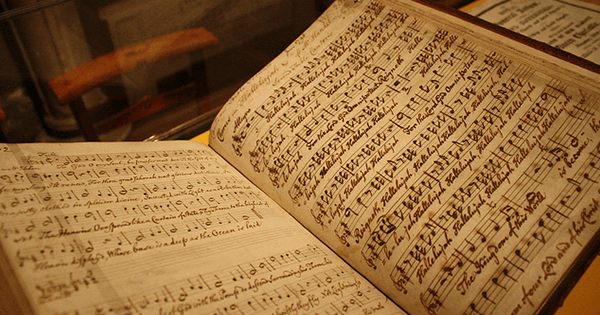

The timing of the orchestra’s birth coincided with a revival of music from the Baroque and early classical eras, and the recordings that the Academy made—its discography would swell to more than 500—helped usher in a new era of interpretation. Until the 1960s, performances of Bach and Handel, to say nothing of later composers such as Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, tended to be unabashedly romantic: big-boned, lush, thickly textured, and slow. This isn’t to suggest that the old ways were necessarily bad. I can think of few more profound and moving experiences than listening to Willem Mengelberg’s 1939 recording of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion; Wilhelm Furtwängler’s interpretations of Bach and Handel from that same era are similarly monumental, as spiritual and transcendent as a Bruckner symphony. Yet those masters took liberties with the scores that would be unthinkable today. Marriner, by contrast, with his chamber music forces, adopted fleeter tempos, achieving greater clarity and liveliness, with thinner textures and more transparency—in other words, a more “authentic” sound. It so happened that the musicologists of the era were starting to better understand just what made up an authentic Baroque and classical sound, and Marriner was able to put this theory into practice.

During their most frenetic period, Marriner and the Academy were making roughly a dozen records a year—concerti grossi by Handel and Corelli, the Bach orchestral suites, Mozart’s Requiem and symphonies, Haydn’s Creation, as well as works that had been languishing in near-obscurity, by such composers as Giovanni Henrico Albicastro and Giuseppe Torelli—ice-cream composers, Marriner called them. The 1969 recording of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons with the violinist Alan Loveday was a revelation: elegant, brilliant, spry, full of poetry and conviction. It sold like mad. An even greater popular success was the soundtrack for the 1984 film Amadeus, with more than 6.5 million copies sold. But Marriner refused to remain in the distant past. He demanded a flexibility from the Academy’s musicians that allowed them to traverse an Elgar symphony as comfortably as they did a Vivaldi concerto. The group’s repertoire stretched well into Romantic terrain, even into the 20th century, with recordings of Schoenberg, Webern, and Stravinsky.

This catholicity, it turned out, was necessary. As more conductors began specializing in historically informed interpretations, absorbing the latest musicological scholarship, performance practices changed again—gut strings were now preferred, string vibrato was banished, orchestral forces became even smaller, tempos were taken even faster. Marriner, meanwhile, remained loyal to the style and sound he had cultivated, insisting on, among other things, the use of modern instruments. And if the more orthodox early-music purists—Roger Norrington, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Trevor Pinnock, and Christopher Hogwood, among them—seemed to pass him by, Marriner remained popular, largely because of the radio. In many ways, the Academy was a dream for classical radio: it performed repertoire that appealed to a large segment of the listening public, and its interpretations were decidedly middle-of-the-road. Marriner may have been forced out of the terrain that he had helped pioneer, but as the ranks of his orchestra grew, they all moved on to other things—to Schubert, Mendelssohn, Wagner, and beyond.

Through it all, Marriner’s baton technique remained understated—not for him the maestro flailing about in balletic fashion, calling attention to himself at the expense of the music. His clear, low-key podium style came directly from his mentor Pierre Monteux, who had been in charge of the London Symphony Orchestra in the early 1960s and who had invited Marriner to attend his summer conducting school in Maine. Like Marriner, Monteux had been a violinist first and a conductor second, and the younger man adopted the older maestro’s ethos. Marriner had initially led the orchestra while seated in his concertmaster’s chair. Under Monteux’s tutelage, he took the bold step of standing up before the ensemble. Undemocratic though this move may have been, Marriner was hooked. “Soon I noticed that the baton has a magic quality,” he said. “Having once held it, I didn’t want to let it go.”

He held that baton until the end. In excellent health into his 90s, he appeared as a guest conductor around the world, maintaining a travel schedule that would have distressed many a younger man. He was, by one estimate, continually on tour for the last 60 years of his life. “If I stopped conducting,” he once told a German newspaper, “I’d die.” But really, the converse was true. Only when he died did Neville Marriner stop conducting.