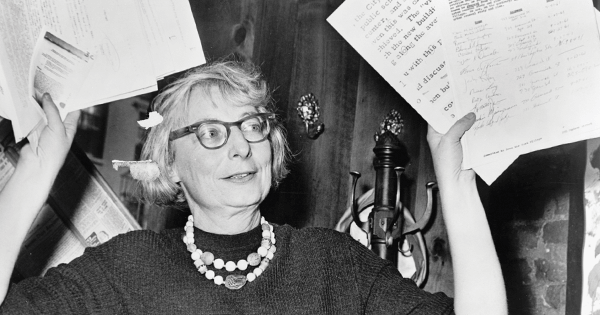

Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs by Robert Kanigel; Knopf, 512 pp., $35

Jane Jacobs was one of the great urbanists of the 20th century. Her 1961 masterpiece, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, which combined extraordinary insight into city streets with a biting indictment of urban renewal, remains a seminal text for would-be urban planners. But Jacobs’s career was larger than a single book, and thanks to Robert Kanigel’s Eyes on the Street, we come to appreciate her intellectual development and professional achievements in all their fullness.

Jacobs’s wisdom was learned on the ground, not in the classroom, which is sobering for those of us who teach for a living. But she began her literary career in high school, publishing poetry, reviews, and interviews in a student magazine. From there, she graduated to an unpaid position with The Scranton Republican, and in 1934, she decamped for New York to become a writer. For the next 18 years, she enjoyed an enormously eclectic career writing and experiencing New York.

Kanigel’s book opens up those early years, which had been hazy even to many devoted Jacobs acolytes. There were a number of temporary, low-paying jobs for which Jacobs was grateful, if only because they helped her learn about her new city. In 1935, she published her first magazine article, in Vogue, which described New York’s fur district, and which already displayed a distinct grasp of urban space. After her father died in 1937, she used some of the insurance money to pay for classes at Columbia, and in 1941, Columbia University Press published her now largely forgotten first book, Constitutional Chaff—Rejected Suggestions of the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Afterward, she joined Chilton’s Iron Age, a trade magazine covering scrap metal prices, and rose from secretary to associate editor.

During the latter years of World War II, Jacobs worked for the Office of War Information (later absorbed by the State Department), where she wrote for the propaganda magazine Amerika, which aimed to convince Russians of America’s virtues. In 1949, she wrote an article on housing for the magazine that was “thick with images of American buildings and structures, set out on the broad American plain, all expressing American health and vitality.” The piece was savaged in the Soviet newspaper Izvestia for ignoring America’s slums. Jacobs responded—ironically, given her future views—by explaining how urban renewal was benevolently making slums a thing of the past.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the independent-minded Jacobs became the target of a McCarthy-era FBI investigation. One interviewee told federal agents that Jacobs “had a complete mind of her own and would not be swayed by the opinions of others,” including communists, which captures her perfectly. Kanigel cites a second informant who “said that to him ‘liberal’ meant communist leanings—though he admitted ‘he had no reason for making this statement’ except that Jane lived in Greenwich Village, where communists were said to live, and he’d heard her say things, though he couldn’t remember what.”

Jacobs resigned from Amerika before facing the FBI’s final verdict on her Americanism, and then began pursuing the work that would make her famous. After joining Architectural Forum in 1952, her attitudes about urban renewal began to change. In the magazine’s July 1955 issue, she published “Philadelphia’s Redevelopment: A Progress Report,” which contained an upbeat description of architect and urban planner Edmund Bacon’s work in the City of Brotherly Love. Kanigel notes that “it’s not clear how much—or even, just possibly, whether—Jane visited Philadelphia to research her story.” Indeed, she had begun her career at the Forum by writing an article that lovingly described new structures in Peru that she had never seen.

When she visited Philadelphia’s redevelopment (for at some point, she did), Bacon showed her how it could replace the crowded mess of a poor neighborhood with beautiful clear vistas. But she saw that although the older areas were filled with “lively and cheerful” people, the new area had only “one little boy—she’d remember him all her life—kicking a tire.” Later, William Kirk, who led a settlement house in East Harlem, helped Jacobs to “see beyond where even her lively curiosity had taken her, to an East Harlem that was much more than it first appeared, something interwoven, connected, whole”—something that was being destroyed by vast public housing towers.

As Jacobs walked the streets, she came to understand them in a visceral way and used her enormous literary gifts to share her knowledge with the world. Her great coming out was at a 1956 Harvard Design School conference, during which she stole the show by arguing that “the open space of most urban development was a ‘giant bore’ whereas it ‘should be at least as vital as the slum sidewalk.’ ” That talk led to her classic 1958 article in Fortune, “Downtown Is for People.” Indeed, the central message of her subsequent work was that cities must serve people—not stand as architectural monuments. The Fortune piece led to Rockefeller Foundation grants that enabled her to write The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Kanigel’s description of Jacobs’s writing difficulties will warm anyone who has struggled with a publishing deadline.

The book was an explosion that changed popular opinion and shifted the field of urban design. Her emphasis on smaller scale, sidewalks, and neighborhood interactions is now deeply embedded into urban planning. She continued to write books for 40 more years. For economists, like me, The Economy of Cities, which illustrates the role of cities in spreading ideas, is a particular favorite. One gripe, though: the archaeological evidence doesn’t support Jacobs’s hypothesis that cities came before agriculture.

Aside from The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs is perhaps best known for her political battles against Robert Moses and his plans for the Lower Manhattan Expressway. The tale is well chronicled elsewhere, but Kanigel gives us depth and balance. Those two attributes make Kanigel stand out among Jacobs’s biographers. He correctly sees her as an “icon of unfettered, incorruptible intelligence” but also sees her flaws. Not every story was well researched. Not every argument was correct. But still, she was great, and Kanigel gives her the great biography she deserves.