The Patriot Slave

The dangerous myth that blacks in bondage chose not to be free in revolutionary America

During the American Revolution, four times more black Americans served as loyalists to the Crown than served as patriots. They joined the British in high numbers in response to promises of emancipation. And yet the enduring memory of black participation in that war would become the image of the faithful slave. The fact of black self-determination during the Revolution, and the bizarre cultural memory that developed to suppress and obscure it, inaugurated a powerful and enduring American theme. The fantasy of the patriot slave continues to haunt us and to limit us. It is a tendency to think of black people as supporting characters in the national drama—not so much as a selfless people (on the contrary, we are often smeared as freeloaders) but as people without any real selves worth bothering about.

The truth is that black people, like all people, tend to act out of personal hopes and personal fears, and not solely to fulfill the wishes or confirm the fears of whites. This may sound obvious, but it has often come as a surprise. White America seems trapped in a dream only occasionally disturbed by dramatic proofs of black agency, or of black indifference to its priorities. But soon the default view reestablishes itself: that blacks are the white man’s boogeyman or burden, his “original sin,” his project for personal moral salvation, or his tool.

W. E. B. Du Bois observed, in 1903, that white interlocutors were always curious about how it felt to be part of what they then termed “the Negro problem.” “Being a problem is a strange experience,” he reflected, “peculiar even for one who has never been anything else.” It is no less strange to be looked upon as a solution—a dumb instrument waiting for the right hand and the right task. The view of the black American as a subsidiary character in the white man’s epic, whether cast in the role of villain or of friend, denies us our own personhood. It also denies all Americans the joint strength of a truly shared national vision, and the stability of a course directed by mutual concern, respect, and concessions.

In this critical election year, candidates are once again vying for the “black vote.” At the same time, some states, bowing to political and economic pressure, have begun to ease the stay-at-home restrictions that diminish the spread of COVID-19, a disease that is far from contained and that has proved disproportionately deadly to black Americans. It may therefore be time to review the history of a persistent national delusion: that blacks are happy to die for the liberty and prosperity of those who would keep us powerless and poor. We are not.

Watson and the Shark, 1778, By John Singleton Copley (National Gallery of Art)

Watson and the Shark, a 1778 painting by the Anglo-American artist John Singleton Copley, provides an early moment of clarity on race in American life. It features a rowboat heavy with men working desperately. Some of them are employed with the oars, while another stands wild-eyed, aiming a harpoon at a shark circling the little craft. Three other men almost tilt the boat toward the viewer in their efforts to save a young man in the foreground, a pale, naked figure sinking into the water, but the victim’s shocked gaze fails to connect with them.

This monumental work established Copley’s reputation on the London art scene in the years after he moved his family to England to escape the Revolutionary War. It captures the moment when Copley’s patron, Englishman Brook Watson, lost his leg to a shark while swimming in the Caribbean in his youth. But perhaps unintentionally, the painting captures another story, too, one that an expatriate American artist would have been uniquely positioned to tell. It expresses a moral tale about race and American destiny that, in one guise or another, has haunted this nation since its founding.

One man in the boat is not bending his efforts toward the rescue: a black man. His portrait is striking for this era of Western painting, in part because he appears to be a real person, an individual, and not the kind of comic caricature so much more common in 18th-century depictions of Africans and African Americans. In the boat, he is the only figure standing still, his stance heroic, even messianic, posed in white, windblown clothing at the pinnacle of the composition. The naked form of the youthful Watson with his streaming blond hair catches the eye, as it was meant to—artists of this era considered the classical Greek male nude one of the highest aesthetic accomplishments in painting. But of all the figures in the painting, only that of the black man would make a complete composition on its own.

That is not to say he is disconnected from the action: in his left hand, he grasps the end of a thick rope, which falls in a looping path down over the side of the boat to loosely encircle Watson’s arm before disappearing into the water. The rope is like nothing so much as an umbilical cord. The black man’s other hand, outstretched and palm down, is in tension with—is definitely in communication with—the upturned white hand of the drowning Watson. And his face is serious. One reads ambivalence there and also trepidation. Although this figure holds the rope, and although he is positioned as the hero of the composition, he has not yet committed to saving the drowning man.

This is a portrait of a man in crisis. Conventionally, the painting is about Watson’s crisis, in the moment of his maiming. But the black man’s crisis at this moment of decision is more severe and more touching. And the artist, a worldly, wealthy refugee from America’s Revolution, could also be communicating an urgent message to the London viewer. The message is that “we”—white, European, Anglo people—cannot make it in the dangerous New World without “them.” That is, without the New World man, this person with African skin in European clothing. It is in the black man’s hands to effectuate the birth of the naked, classical Greek figure into the time and place of his new life in America. And, the artist seems to worry, it may be in the black man’s hands to refuse that birth.

American slavery, before and after the American Revolution, was a relationship of intimate violence. When I teach the history of slavery, that intimacy surprises students, as do the pervasive and explicit acknowledgments by whites, in slave codes, in trial transcripts, and in memoirs, of the enslaved person’s intellect and humanity. This surprise is a product of the current moment in American history, not of the facts of life in a family or on a plantation that included both enslaved and free people. Looking back on antebellum slavery from the perspective of the 21st century requires looking through the distorted lens of almost a hundred years of Jim Crow. The sensibility of the 20th century’s laws forbidding touching, forbidding “miscegenation”—a sensibility that meant that if a black child accidentally dipped his toe into a whites-only swimming pool, management might drain the pool before opening it for use again by white people—reflects a culture of fastidious separation that developed only after slavery’s end, an anxious reaction to the loss of a more brutal racial hierarchy.

But the experience of slavery was one of closeness, not separation. Black people worked as head planters, expert agriculturalists, foremen and overseers, skillful artisans in white-owned factories. They ran white households as butlers and worked as chefs, huntsmen, midwives, and breeders of livestock. White masters turned to these black people for advice about their businesses, their laborers, the methods of production. An enslaved man might be the master’s half-white uncle or cousin, or even his brother. A white man’s black property might be the friend he had grown up playing and squabbling with, before one was trained for tyranny and the other for subjugation. For that matter, enslaved women breastfed white children, provided the difficult and intimate care the white elderly required in their failing years, and were involved in long-term sexual relationships with white men whose dominion over their bodies the law confirmed and protected.

These relationships must have involved a constant tension and, on the part of the white owner, tremendous fear of the resentful impulses of the people who prepared his food and cared for his dependents. On large plantations, the master’s fear of the enslaved people in his household would have joined with a sense of profound alienation from the enslaved families he kept working in his fields. In spite of laws like one in South Carolina outlawing drumming and black social gatherings, there was no way to prevent slave quarters from becoming places where black people might experience, in moments of exhausted respite, their own relationships and forms of spirituality, and the comforts of the music and other forms of cultural expression from the unimaginably distant homelands of their forebears. A white master could not help but fear that behind those unlocked doors, enslaved men and women might even engage in dangerous conversations and nurse private hopes and yearnings.

The British understood these fears and tried to exploit them. In 1775, Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia, became frustrated with the resistance to imperial tax laws and angry that some Virginians had begun to stockpile weapons. He decided to teach them a lesson by issuing a proclamation promising freedom to any slave who left a rebellious master and came ready to bear arms in defense of the crown. Many slaves flocked to his banner. In Virginia, where it was illegal for masters to emancipate their slaves, Dunmore’s Proclamation held out what must have seemed a unique chance for self-determination. And the psychological effect of this “Ethiopian Regiment,” marching to war wearing sashes proclaiming “Liberty to Slaves,” was profound for black Americans throughout the colonies. In Philadelphia that year, when a white woman “reprimanded” a black man for not jumping into the street so that she could use the sidewalk, he replied, “stay you d[amne]d white bitch, ’till Lord Dunmore and his black regiment come, and then we will see who is to take the wall.”

Historians have long argued over whether the American Revolution destabilized slavery, and whether so-called charters of freedom like the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution committed the new nation to emancipation. Edmund Morgan, Sean Wilentz, and Gordon S. Wood, among others, have eloquently argued that the Revolution and those early documents created a nation based on the principle of (eventual) equality. There is doubtless some truth to that. In the North, where whites enslaved people in fewer numbers and where slavery was far less important to the economy, the Revolution ushered in real and lasting change. Some states, like Rhode Island, took a lesson from Dunmore and promised emancipation to slaves who agreed to join the militia. Other northern states, like Massachusetts, allowed men to avoid military service by sending a servant to fill their place. Some men sent their slaves, offering freedom as compensation. Historians estimate that 5,000 black men fought for the patriot cause. But black Americans living in, say, Washington and Jefferson’s Virginia experienced the Revolution differently. To an enslaved American in the South, trying to make choices about his life, it would have seemed that he could grasp freedom for himself, his children, or even his great-great-grandchildren only by joining the British side of the fight—or by taking advantage of the chaos of war to disappear.

Indeed, in the South, the Revolution was fought in part to protect slavery. According to historian Douglas Egerton, Lord Dunmore’s 1775 Proclamation helped to convince “irresolute masters to join the call for Independence.” For these incipient patriots, Dunmore’s threat to the institution of slavery was the one insult they could not bear. The following year, Jefferson made this point explicitly. We all remember the part of the Declaration of Independence proclaiming that “all men are created equal” and “that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights,” including “Liberty.” Less well remembered is an item among the complaints the Declaration listed to justify independence from Britain: Americans were rebelling, it said, because the British crown had “excited domestic insurrections amongst us”—insurrections of slaves. This statement, and many others like it, undergird the argument of historians who hold that in spite of all the liberty talk of this period, the Founding Era wasn’t about freedom or equality at all. As the historian Alan Taylor put it, some Americans, while demanding liberty from the British, simultaneously felt that “white men could be free only if allowed to hold blacks as property.” Although never implemented, a law passed in Virginia to promote enlistment would have granted “one able bodied healthy negroe Slave between the age of ten and forty years” to each new recruit.

And so, even though the Revolution inspired white northerners to move toward emancipation, and even though Virginia changed its law after the war to allow masters the discretion to emancipate their own slaves, it’s important to see these changes soberly, from the perspective of a contemporary black American observer. To a person whose fate was on the line, it would have been clear that the new nation had no intention of ending the system of kidnapping, family separation, rape, theft, and forced labor that the economy of the South depended on. No fatal misgivings prevented northern representatives to the Constitutional Convention from founding a nation in partnership with representatives from the southern states committed to the position that it was fine to torture other human beings for personal profit. As the historian Paul Finkelman has persuasively argued, the antislavery arguments of such prominent delegates as George Mason and Luther Martin did not carry the day. Although some northerners grumbled about the additional voting power the three-fifths clause gave southern states, aside from one moving speech by Gouverneur Morris, most of the qualms that northerners expressed concerned sectional power and economics, not morality. As Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts put it, “Blacks are property, and are used to the southward as horses and cattle to the northward; and why should their representation be increased to the southward on account of the number of slaves, than horses or oxen to the north?”

Indeed, by protecting the political power of the states most dependent on it, the new Constitution tended to strengthen the institution of slavery, at least in the near term. Historical counterfactuals are difficult, but it is possible that if the American colonies had remained in the British Empire, black Americans could have benefited from Britain’s 1833 law abolishing slavery. But because American patriots had, in the old cliché, “struck a blow for liberty,” they were not in the empire in 1833. And as a result, after the enslaved people of Britain’s Jamaican colony were formally freed, another entire generation of black men and women remained in bondage and penury under American constitutional government.

And the experience of slavery remained one of both violence and intimacy. White Americans spoke of slaves with pity, for example, when the Virginia legislature threatened to execute those “unfortunate people” who had been “seduced” by Dunmore’s promises. There was pity in these relationships—how could there not be? Again, the humanity of their bondsmen, the unfairness of their fate, would have been obvious to most slave owners. There was also a great deal of shame. Jefferson frequently lamented slavery, which he called a cause for “heavy reproach,” a system that by “permitting one half the citizens thus to trample on the rights of the other, transforms those into despots, and these into enemies.” In his Notes on the State of Virginia, he admitted: “I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep for ever.” But the proof the Revolution gave, that enslaved men and women would grasp freedom and take up arms if they could, only amplified white Americans’ enduring fear of “insurrection.” That is one reason why, in spite of their regret over the situation, these Founders did not contemplate emancipation. Their pity and shame were limited by a horror of receiving a just return on their investment. Masters feared the vengeance a black population might exact if not continually beaten into submission. In Jefferson’s words, “[W]e have the wolf by the ear and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go.”

Their pity was also limited by greed and ambition—and not just personal ambition, but their patriotic hopes for national greatness. When Americans won the war for independence, the former colonies were left alone on a continent with powerful imperial rivals for territory and dominion, including the British to the north and the Spanish to the south and west. Americans feared that without the economic power the enslaved workers produced, the new nation could not possibly remain independent and thrive. They feared, in other words, that “we,” white Americans, could not make it without “them,” the half brothers they stole from and savaged.

Like all intimate relationships that involve force, that between master and slave relied on a great deal of fiction: the master told the slave that ownership was benevolence; the slave performed fidelity for the master. The American Revolution forced a reckoning. Slave owners looking to rebuild their lives after the dislocation of war faced a double deprivation. They had, of course, lost all of those black men and women who had escaped or died in the attempt. A provision in the Treaty of Paris addressed this, demanding that Britain’s fleets withdraw “without causing any Destruction, or carrying away any Negroes or other Property of the American inhabitants.” Perhaps more serious, however, was the slave owner’s loss of those tacit narratives—including the fiction of the slave’s resignation to his condition—that had made the master’s own crimes bearable and helped to dull his rational fear.

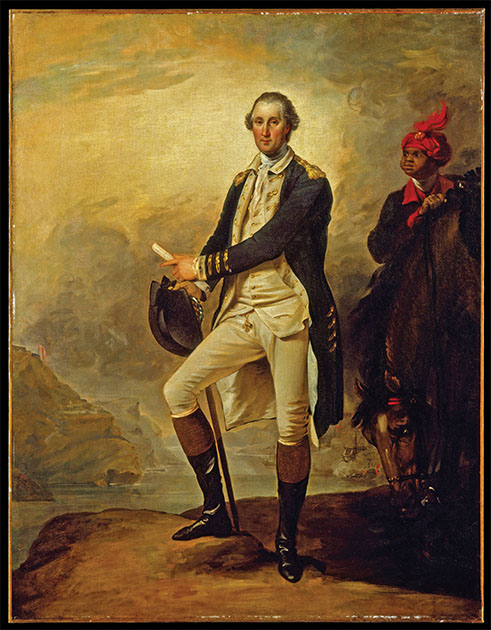

Washington, 1780, By John Trumbull (Wikimedia Commons)

A comforting fable developed in response to this anxiety. In the wake of the Revolution, Americans wanted to believe in an archetype of the loyal black servant, happy to support the nation in any capacity, content with his half life in the white man’s shadow. So, even though four times as many black men had joined the British side, an image of the patriot slave became part of how Americans remembered the Revolution, and how, through the cult of George Washington, they constructed a national identity.

The 1780 portrait of Washington by John Trumbull helped establish this theme by prominently featuring Washington’s slave, William Lee. Indulging an affectation common to that era, the artist put Lee in a feathered turban. Washington stands centered on a rocky promontory against a backdrop of storm clouds and a distant sea scene. Taken together with the clouds, the red notes on a ship in the distance, on the horse’s bridle, and in the leaping flame of the turban feather give the impression that Washington is encircled by the fire and smoke of war. The victorious general points toward the only area of clear sky, his finger indicating a planted flag. The figure meant to represent Lee stands behind Washington’s horse, gazing toward Washington for direction.

Lee is also prominent in Charles Willson Peale’s 1779 George Washington at Princeton. Peale’s is another triple portrait of the general, his horse, and his slave, although here the horse may have received higher billing. And this work was also popular—Peale reproduced it to order at least 20 times. The best versions of the painting, including the original in the collection of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the copy hanging in the U.S. Senate Gallery, show a brown-skinned Lee in profile. His shadowed figure is part of a visual pile of the accoutrements of war, including horseflesh, weapons, and flags. Although both Peale and Trumbull purport to depict the same historical figures, their versions of Lee do not resemble each other. Unlike Washington’s, Lee’s actual features were not important to the portraitists. He is present in these images not as a person but as one of the tools of Washington’s greatness, and as a symbol of the essential fidelity of the black American.

The image of Washington with Lee beside him appealed strongly to the American psyche. It reappeared in moments of anxious reflection on the national character, when Americans looked back to Washington to find a paragon of public virtue. In 1859, The Constitution, a Washington, D.C., newspaper, published an article titled “The Personal Appearance of Washington,” in which an anonymous author described likely made-up encounters with the “chief.” One of those memories was from the summer before Washington died: “He rode a purely white horse” that “almost seemed conscious that he bore on his back the Father of his Country.” (Pause a moment—the horse had a country?) After dwelling on Washington’s horsemanship, the author continued,

Behind him, at the distance of perhaps forty yards, came Billy Lee, his body servant, who had periled his life in many a field, beginning on the heights of Boston in 1775, and ending in 1781, when Cornwallis surrendered, and the captive army, with unexpressible chagrin, laid down their arms at Yorktown.

Although the article was about Washington’s appearance, the author lavished attention on his companion:

Billy rode a cream-colored horse of the finest form, and his old revolutionary cocked hat, indicated that its owner had often heard the roar of cannon and small arms, and had encountered many trying scenes. Billy was a dark mulatto. His master speaks highly of him in his will, and provides for his support.

During the 19th century, many Americans felt that Washington represented the nation at its greatest, and that by emulating his strengths and virtues, the country could achieve its highest destiny. Among his admirable attributes was the fact that he had a very faithful slave. Lee’s loyalty was something that Americans knew and valued about the first president, just as they knew how well Washington sat a horse, maintained camp discipline, and guarded his personal character. Indeed, it was something that helped to define him and, through him, the nation.

Lee was a real man, but it is difficult to get to know him. No historian has written a book-length biography of him. It seems unlikely that this would be true of any white person who rode with Washington to battle, stood at his side during wartime councils, and traveled with him to Philadelphia for the Constitutional Convention. For Lee, as with so many of our black ancestors, there is not enough documentary evidence to reconstruct a full life story. Instead, we are left to catch glimpses of him through stray papers. Washington’s cash accounts show that the year after the death of William Lee’s first master, Colonel John Lee, the colonel’s widow hastened to sell off two half-white teenagers: “Mulatto Will” and his brother Frank. She received a good price for them. George Washington’s papers show that he trained Frank as a butler and William in horsemanship and hunting.

Washington’s papers tell us that William Lee then went to war as Washington’s personal valet. An eyewitness to the Battle of Yorktown remembered that “when the last redoubt was captured, Washington turned to Knox and said, ‘The work is done, and well done;’ and then called to his servant, ‘Billy, hand me my horse.’ ” This recollection punctuates the decisive battle of the war with a reminder that Washington’s slave stood on hand, ready to serve. These occasional mentions by other men give Lee’s experience in the war some color, but through a veil of white contempt. An army physician recalled that he saw Lee halting at an overlook “and, having unslung the large telescope that he always carried in a leathern case, with a martial air applied it to his eye, and reconnoitred the enemy.” Note that he said “with a martial air,” as though Lee were a child playing at war.

We also know that Lee fell in love with and married a black woman while living with Washington in Philadelphia. We know this because Washington wrote to his business manager that he felt obligated to gratify Lee’s request to bring his wife to Mount Vernon when the war ended, “if it can be complied with on reasonable terms”—although in truth, said the great man, he had “never wished to see her” again. One wonders what the free woman did, or if it was just the fact of her freedom, that made her so obnoxious to the general. Washington’s letters and papers also tell us that after the war, in the course of his servitude, Lee fell twice, breaking both of his kneecaps. Disliking the idea of an idle slave, Washington converted his old campaign companion into a shoemaker, work Lee could do sitting down, and expected him to make enough shoes to keep the plantation well supplied.

Washington did leave a final note about Lee in his will, a document widely reproduced in national newspapers. The will granted William “(calling himself William Lee)” a pension and also his freedom, if he wanted it—a tacit acknowledgment that the deathbed emancipation may have come too late for its beneficiary to enjoy it. And even these small gestures seemed to have earned Lee some resentment. In a recollection of Washington’s life, one of the general’s descendants painted Lee as “a most interesting relic of the chief”—that is, a leftover thing from Washington’s life suitable for a tourist to gawk at. Yet, noting that Lee had a house and a pension, he spoke disapprovingly of Lee’s turn to alcoholism. A home to live in and a guaranteed income had made “Billy” “a spoiled child of fortune. He was quite intemperate at times.” Charles Willson Peale, who had been propelled to fame in part by his early portrait of the general and his slave, used a visit to Mount Vernon to lecture Lee “on the subject of health and right living.”

But let’s allow the man, William Lee, to rest. In this case, it was not the person who made the greatest impact on American culture but the idea of him. Lee was hardly unique in this. It was likewise the idea of the slave rebels at Stono in 1739, of Denmark Vesey in 1822, and of Nat Turner in 1831 that created terror in the white imagination, justifying cruelties toward other black people far out of proportion to the real accomplishments of those freedom fighters. The terrifying image of the vengeful slave was one side of a coin. On the other side was Billy Lee, the docile creature depicted by Trumbull and Peale. So powerful was the idea of Billy that it was not undermined by the fact that many of Washington’s slaves fled Mount Vernon during the war. It survived even as, the historian Erica Armstrong Dunbar has shown, George and Martha Washington spent decades pursuing a woman who had managed to escape the executive mansion in Philadelphia. It endured undiminished by the ever-present genre of the runaway slave announcement, advertisements scattered through any 19th-century newspaper, offering rewards for slaves who had taken advantage of a moment of inattention or trust to steal themselves away.

The myth remained potent even to describe people such as Christopher Sheels— like Lee, one of Washington’s body servants—who had failed in an attempt to free himself. Washington discovered Sheels’s plot to escape with his fiancée in a boat docked at Alexandria. A surviving letter shows how Washington kept his discovery of their plans secret while colluding with the fiancée’s owner to foil their attempt. The next mention of Sheels in the documentary record is from three months later, in a diary account by a witness to Washington’s last moments. The recollection, first published in 1837, mentions that Sheels remained standing for many hours by Washington’s bedside as the general slowly expired. A Currier and Ives print made much of this detail. The firm’s Death of Washington print featured a slave standing by Washington’s bed at mournful attention. Some renderings also show another slave kneeling, distraught, or a cluster of slaves, visible through an open doorway, weeping and consoling each other. These figures stood as a symbol of national sentiment—the way this era of portraiture often included a dog gazing at the master to symbolize loyalty. This is not to say that Sheels did not care for George Washington; people often love their abusers. It’s just to point out that what the public wanted—and these inexpensive prints were so popular that the firm printed eight different versions of this scene—was the reassurance that the image offered. There was an appetite for an exaggerated show of a slave’s love for the man who personified the nation, a love that proved itself anew in that man’s most vulnerable moment.

That southerners had convinced themselves of this fable is evident in the way they talked about slavery. Northerners were wrong to grumble about the South’s additional representation in Congress due to the three-fifths clause, said South Carolina Congressman Charles Pinckney in 1820. The only thing unfair about it was that black slaves were not counted more. Slaves had always been “more valuable to the Union … than any equal number of inhabitants in the Northern and Eastern states,” the congressman said, pointing to the work slaves had done during the Revolution to build patriot fortifications and fill out the ranks of the northern militias. And,

notwithstanding in the course of the Revolution the Southern States were continually overrun by the British, and that every negro in them had an opportunity of leaving their owners, few did; proving thereby not only a most remarkable attachment to their owners, but the mildness of the treatment from which their affection sprang.

In fact, 20,000 enslaved people responded to the 1775 Dunmore Proclamation and the even broader 1779 Philipsburg Proclamation and served with the British forces. This striking figure, historian Maya Jasanoff has noted, made the American Revolution “the occasion for the largest emancipation of North American slaves until the U.S. Civil War.”

But southerners persisted in this fantasy. Slaves and masters complemented each other, they explained, to the benefit of each. In the words of a University of Virginia professor in the 1850s, while the black man “is naturally lazy, and too improvident to work for himself, he will often labor for a master … because he feels that, in his master, he has a protector and a friend.” Among slaves’ essential strengths, said the South Carolina politician William Harper, were his “fidelity—often proof against all temptation—even death itself,” along with “a disposition to be attached to, as well as to respect those, whom they are taught to regard as superiors.” There might be some unpleasantness between master and slave, admitted another politician, James Henry Hammond, but the same was true of all loving relationships. “Slaveholders are kind masters, as men usually are kind husbands, parents and friends,” he explained.

In each of these relations, as serious suffering as frequently arises from uncontrolled passions, as ever does in that of master and slave, and with as little chance of indemnity. Yet you would not on that account break them up.

This story was so consistent and so pervasive that in the 1850s, an Englishman traveling through the southern states ventured to ask a slave to confirm it. The enslaved man explained to him that he had been born in Virginia, sold “on account of the bankruptcy of his owner,” and had then been “parted from a sister” and had “never heard of her since.” In the face of this tale of helplessness and heartbreaking loss, the Englishman thought to “try him” by saying he “supposed the slaves were pretty well treated.” The enslaved man replied that their “treatment depends entirely … on the person they belong to. Indeed, how can it be otherwise?”

“But,” said I, “we are told that you prefer slavery, and would not be free if you could.” His only answer was a short, contemptuous laugh.

The Englishman reflected that he “almost felt ashamed of having made so silly an observation.” But he could have been forgiven for his mistake, since Americans in the best position to know better held onto that silly idea even through the Civil War. One southerner admitted, as late as 1864, to the belief “that a very large number of the negroes will not accept their freedom and that, by one name or another, pretty much of the old relations will be re-established.” According to the historian Eugene Genovese, when black people disappointed this expectation by embracing freedom, it left a class of former masters resentful and traumatized.

The story that these Americans wanted to believe, that they resisted giving up even in the face of all the contrary evidence, is beautifully captured in another painting, the antebellum masterpiece Washington Crossing the Delaware. The 1851 canvas by Emanuel Leutze shows General Washington standing heroically in the center of a boat, crossing the frozen river by night to surprise a Hessian encampment and accomplish a victory that would prove a turning point in the war. This painting could be the next panel in the story that begins with Copley’s Watson and the Shark. It is white America’s answer to the warning implicit in the earlier painting, a white man’s fantasy about how the narrative must unfold. Certain details are the same: both are monumental water scenes featuring a pyramid of earnest figures in nearly identical wooden boats. But in the later image, the black figure has rescued the white man, who now occupies the place where he once stood. The white titular subject of the painting now commands the little craft, clothed in military glory, while men of all races ply the oars, helping him toward his destiny. As for the black man—well, William Lee is also there. But in strong contrast to the humanity and individuality of the black figure in the Copley painting, the black figure in Washington Crossing the Delaware has his face turned away and in shadow. He has made his choice, throwing his lot in with the group. Now he sits anonymously at the oar, more a symbol than a man, and almost under Washington’s foot.

The patriot slave still exercises a powerful sway over the American imagination. This is the character Donald Trump refers to when, in the midst of his rallies, he tells the crowd to “look at my African American!” It is not the person himself, that lonely black attendee, but the idea of him. Indeed, without understanding the pull of this old fable, it is difficult to explain the common spectacle of Trump’s white supporters displaying “Blacks For Trump” paraphernalia at his rallies.

And the delusion of the patriot slave is not partisan. Some Democrats also see the black voter as an anonymous figure who can be counted on to toil away at the oar, asking nothing for himself. It is a self-defeating attitude. If black turnout in 2016 had matched that in 2012, Hillary Clinton would have won the Electoral College. And yet many Democrats continue to take black voters for granted, entertaining the idea of nominating candidates who cannot connect with black communities, or who have used prior public office to harass and disparage us.

In reality, we black Americans see ourselves as the protagonists in our own story, and not merely as the helpmeets to others. There is a message in the poll numbers from the last election: to paraphrase James Baldwin, I am not yours. White Americans ignore this message at their peril. Like Copley’s central figure in Watson and the Shark, the black voter asked to rescue this country may well pause a moment to wonder which is the more dangerous monster in the water. It is a painful fact, but one that cannot be brushed away, that history has taught us to doubt whether our participation will ever earn our welcome as full members of our nation. White Americans must learn to close this gap, and quickly. Reach out and grasp our hands as equals—or we both drown together.