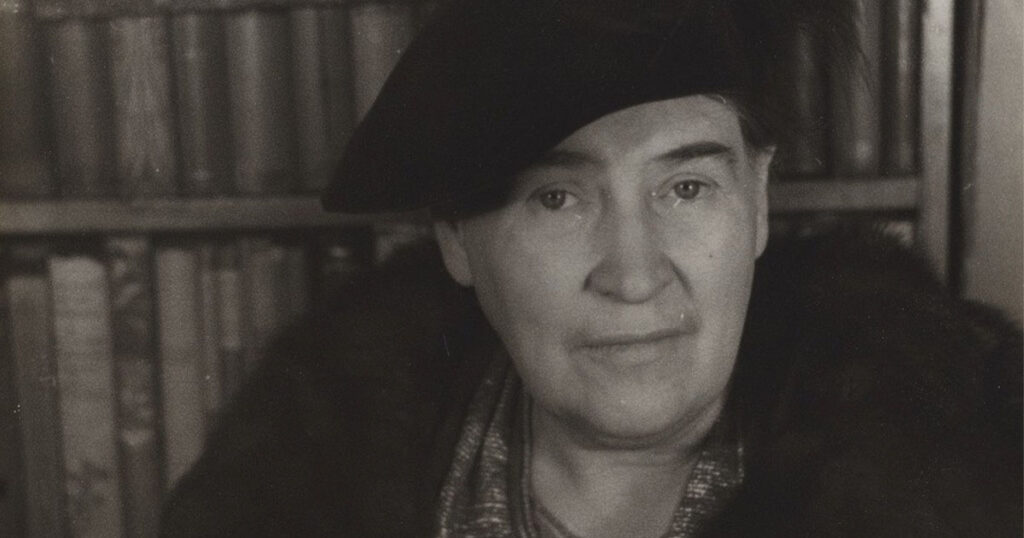

Chasing Bright Medusas: A Life of Willa Cather by Benjamin Taylor; Viking, 192 pp., $29

Willa Cather loathed biographers, professors, and autograph fiends. After her war novel, One of Ours, won the Pulitzer in 1923, she decided to cull the herd. “This is not a case for the Federal Bureau of Investigation,” she told one researcher. Burn my letters and manuscripts, she begged her friends. Hollywood filmed a loose adaptation of A Lost Lady, starring Barbara Stanwyck, in 1934, and Cather soon forbade any further screen, radio, and television versions of her work. No direct quotations from surviving correspondence, she ordered libraries, and for decades a family trust enforced her commands.

Archival scholars managed to undermine what her major biographer James Woodress called “the traps, pitfalls and barricades she placed in the biographer’s path,” even as literary critics reveled in trench warfare over Cather’s sexuality. In 2018, her letters finally entered the public domain, allowing Benjamin Taylor to create the first post-ban life of Cather for general readers.

Chasing Bright Medusas is timed for the 150th anniversary of Cather’s birth in Virginia. The title alludes to her 1920 story collection on art’s perils, Youth and the Bright Medusa. (“It is strange to come at last to write with calm enjoyment,” she told a college friend. “But Lord—what a lot of life one uses up chasing ‘bright Medusas,’ doesn’t one?”) Soon she urged modern writers to toss the furniture of naturalism out the window, making room for atmosphere and emotion. What she wanted was the unfurnished novel, or “novel démeublé,” as she called it in a 1922 essay. Paraphrasing Dumas, she posited that “to make a drama, all you need is one passion, and four walls.”

Chasing Bright Medusas is an appreciation, a fan’s notes, a life démeublé. Taylor’s love of Cather’s sublime prose is evident and endearing, but in his telling of her life, context is sometimes defenestrated, too. When Taylor sets an idealistic Cather against cynical younger male rivals, we learn of Ernest Hemingway’s mockery but not of William Faulkner’s declaration that the greatest American novelists were Herman Melville, Theodore Dreiser, Hemingway, and Cather. Taylor rightly notes that Cather’s First World War novel differs from Hemingway’s merely in tone, not understanding; A Farewell to Arms and One of Ours, he writes, “ask to be read side by side.”

Taylor is a distinguished chronicler of gayness, who left Fort Worth for doctoral work at Columbia, during the crucible of the AIDS years, and taught at Washington University and The New School. His previous 10 books are slender, the style enameled, the gossip excellent, and he genre-blends with verve, slipping from memoir to travel writing to belles-lettres: a portrait of his friend Philip Roth, an homage to Naples, a pint-size but illuminating introduction to Proust’s life and times. Cather seems a natural follow-up; she and Proust were contemporaries, Taylor notes, and though “he died at fifty-one, she at seventy-three—both vanquished lesser selves along the rough path to fulfillment of their aims. Both became geniuses through traceable feats of will.”

Cather newcomers will appreciate Taylor’s perceptive readings of major works like The Song of the Lark and The Professor’s House; book clubs and survey courses will cheer. Taylor long taught a college course titled “Other People’s Secrets,” but here he shields the privacy of a writer he reveres, downplaying her two long relationships, both with women (though Cather’s companion Edith Lewis is not, as Taylor says, buried at her feet). He also mutes a third great presence in her story: the bright Medusa of critical response and public perception. Cather’s life is a biographer’s quicksand, and sex is the least of it. She is both an American writer of the very first rank and a celebrity handler’s nightmare, this plus-size chain smoker from Nebraska with her teenage trans years, her ease with guns, her workaholism (a million words of journalism alone), her southern accent, her filial piety, her utter refusal to bow.

Not much Dark Cather surfaces in Bright Medusas—a pity, for she was a genius of horror. My Ántonia brims with bizarre ways to die (thrown to ravening wolves, suicide by threshing machine); carp devour a little girl in Shadows on the Rock; and One of Ours rivals Cormac McCarthy for mutilation and gore. Cather repeatedly changed her name and lied about her birthdate, as a professional time traveler must, on the page and in life. She saw her mother weep for a Confederate brother lost at Manassas, rode the Plains six years after Little Bighorn, was the first woman to receive an honorary degree from severely masculinist Princeton, and though in failing health, spent World War II writing back to GIs who read her work in Armed Services Editions paperbacks, especially the ones who picked up Death Comes for the Archbishop, assuming it was a murder mystery. She died the same spring that Elton John and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and David Letterman were born. She is one of ours.

Cather strode the decks on rough Atlantic crossings and climbed Colorado canyons in the dark, no bodyguard required, then or now. Her friend D. H. Lawrence advised critics of American literature to trust the artist never, the tale always. Cather was wonderfully wily at image management, but she trusted the reader above all, as should we.